Winter 2016

Sino-Japanese Relations during the Obama Presidency

– Ming Wan

Like Obama and his predecessors, it would make sense for the next American president to combine cooperation and toughness in the Asia-Pacific region.

The Sino-Japanese relationship is an essential piece in the puzzle of global geopolitics and geoeconomics. China has the second-largest economy, while Japan has the third-largest. It is appropriate to look at it from the lens of the Obama presidency as part of a special issue on his administration’s diplomacy. However, viewing the relationship between two other countries from the angle of a particular American president inevitably links to an assessment of that president’s foreign policy performance, because it is supposed to have occurred “under his watch.” However, the Sino-Japanese relationship has its own history, logic, and dynamics that do not coincide neatly with the periodization of an American presidency. Chinese and Japanese scholars generally periodize their bilateral relations based on the terms of their respective leaders. This periodization offers a far more robust framework for analysis. Thus, this article starts with how the two Asian great powers have dealt with each other, and then superimposes the American presidency on the landscape of Sino-Japanese relations.

There are different ways to study Sino-Japanese relations. I myself have tried a few. One may zoom in or zoom out, being more specific or general. For example, one may focus on leader personalities and domestic politics in the relationship. On the other end, one may provide abstract explanations. One may, for instance, view the recent tensions in Sino-Japanese relations as reflecting a “power transition” problem, which arises when a rising power poses a structural challenge for the status quo power and for the whole international system. Another way of understanding the relationship is to compare it with other bilateral relationships such as U.S.-China relations, U.S.-Japan relations, or Sino-Russian relations.

In this study, I will focus on the “structure of bilateral relationships.” I have found this to be a more productive approach over my years of research on this relationship. Whether a relationship works or not has much to do with how it is managed. In particular, we should pay close attention to landmark events and turning points. We may not necessarily know ahead of time which event may be a defining one, but it would behoove us to look at those recognized landmarks to discern patterns and trends, which will inform our projection of future developments.

It is difficult to predict future developments partly because people ascribe different levels of importance to the same events. That is why the bilateral relationship structures are fundamentally social. The Chinese and Japanese think in their own ways, informed by their historical experiences and social environments. Their mindsets and calculations are comprehensible if people pay attention. At the same time, Sino-Japanese tensions are not only in people’s heads. There are real clashes of material interests, even if they are filtered socially. It is the complex interaction between material and ideational forces that truly matters.

The Dynamic of Sino-Japanese Relations

China and Japan had no diplomatic relations from 1952 to 1972. After the diplomatic relationship was normalized in 1972, the two countries had sometimes contentious yet stable and expanding ties for the next two decades. This came to be known as the “1972 system,” a social construction of the relationship. It was anchored in strategic calculations against the Soviet Union. Japan wanted access to the Chinese market and supplies of raw materials, and after 1978 it offered economic assistance in exchange. At that time, China accepted that deal with its reform and opening initiative. Yet all this cooperation was contingent upon a historical understanding of Japan’s past aggression. The Japanese apologized for their past transgressions, but also felt balanced with the Chinese leaders’ expressions of forward-looking wishes and admiration for a more advanced Japan. A generation of influential Chinese and Japanese individuals made this system work through both sincerity and manipulation.

The 1972 system came under stress after the 1989 Tiananmen Square incident and the end of the Cold War a few years later. The international standings of China and Japan were now drastically different; China had been isolated by the West, and Japan had emerged as an economic superpower. Tokyo tried to restructure its relations with Beijing based on a strong desire to end the need to apologize for the past. The Japanese viewed this focus on historical understanding as a special feature of the bilateral relationship, one that was biased against them. The Chinese needed Japan’s assistance to break out of the Western isolation and thus did not challenge Tokyo’s proposed restructuring. However, one could sense their unease about Japan’s policy shift to normalcy and rise to global prominence. The Chinese view historical understanding as the very foundation of the bilateral relationship. The Chinese government began to promote nationalism in the early 1990s. Initially, this decision was not intended as a condemnation of Japan; however, any effort to promote nationalism in China inevitably led to Japan being targeted, because the Chinese Communist Party ties its legitimacy to its struggle against Japanese aggression.

Yasukuni was not a new issue in Sino-Japanese diplomacy; what was new was Koizumi’s defiance of strong Chinese and Korean criticism and domestic opposition.

Sino-Japanese relations began a slow but sure downward trend in the late 1990s, yet the two governments basically managed to maintain bilateral relations. The two countries entered a period of high tension between 2002 and 2006. Koizumi Junichiro, who began his term as prime minister in April 2001, pledged to visit the controversial Yasukuni Shrine every year as prime minister on August 15, the anniversary of Japan’s surrender in World War II. The Chinese and Koreans object to prime ministerial visits to Yasukuni Shrine because it enshrines the names of Class A war criminals. Both countries view these official visits as evidence that the Japanese government no longer repents for its past aggression and invasions of Asia. Yasukuni was not a new issue in Sino-Japanese diplomacy; what was new was Koizumi’s defiance of strong Chinese and Korean criticism and domestic opposition. He wanted to restructure the Sino-Japanese relationship in a way that was not acceptable to Beijing. All meaningful government-to-government exchange froze, particularly on the top level. Yet economic exchange continued to expand. Thus, the relationship was described appropriately as “politically cool but economically hot.”

Koizumi’s personality played an important role in the tension in the first half of the 2000s. He was strong-willed and popular in Japan. Yet there was a generational change in the country. Younger Japanese were fatigued with what they viewed as China’s insistence on Japanese apologies, and were anxious about their economic prospects when was declining relative to China. In Japan, right-wing views were gradually moving into the mainstream .

The Sino-Japanese relationship improved in 2006–10 during the term of the next prime minister, Abe Shinzo. Abe visited quickly to patch things up. He served only for a year. Fukuda Yasuo, then Aso Taro, succeeded Abe as prime ministers, each serving for about a year. Fukuda in particular set a positive tone for Japan’s China policy. Chinese president Hu Jintao’s visit to Japan in May 2008 constituted the peak in this recovery period. The two governments reached a general understanding on the dispute on the overlapping exclusive economic zones in the East China Sea. However, apparently due to strong domestic criticism, Hu backed away from proceeding with a binding agreement on the East China Sea.

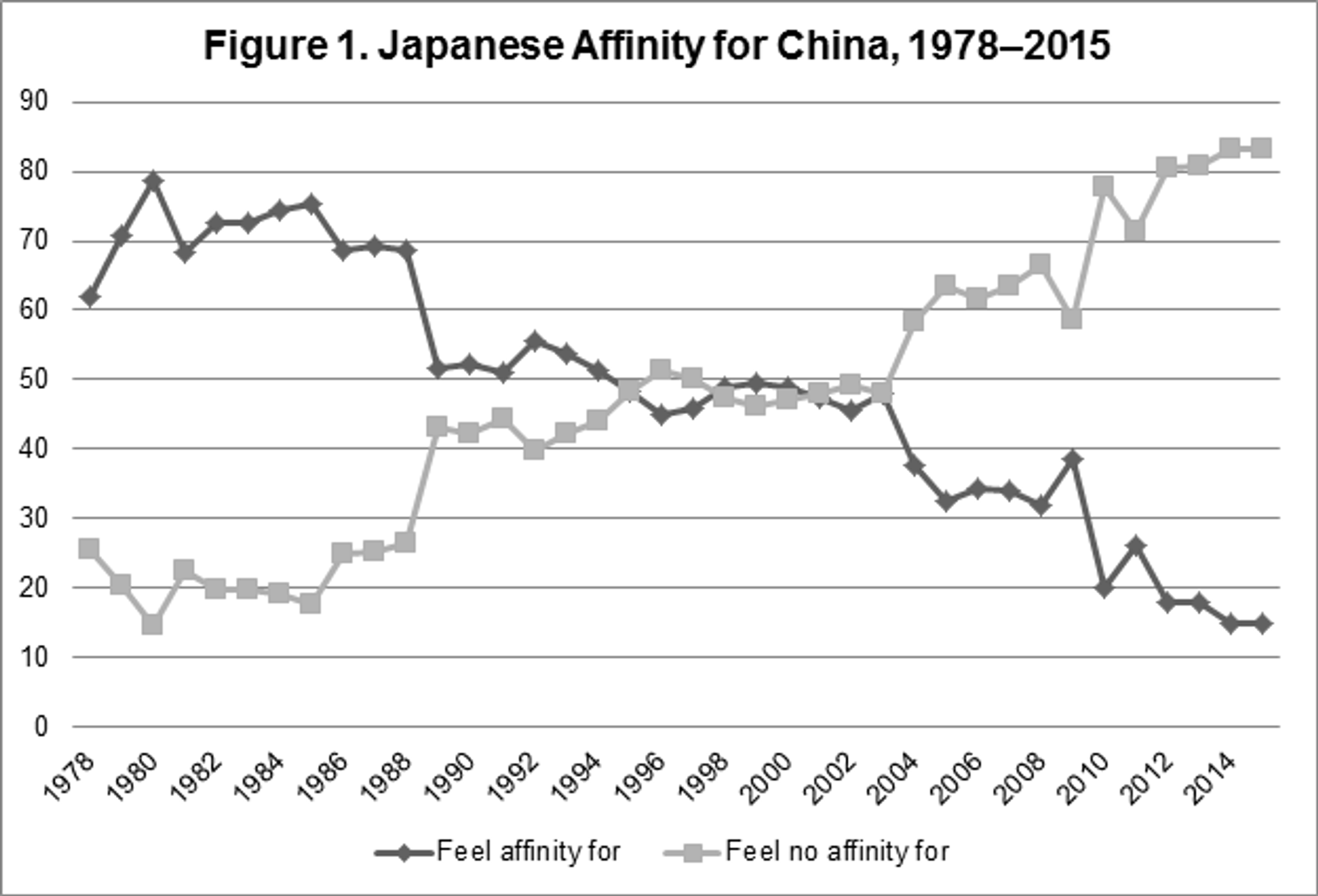

Starting with Abe’s 2006 visit to China, the two sides used colorful expressions to describe the progress in warming official ties. Abe’s visit was termed “ice-breaking,” followed by trips characterized as “ice melting” and “warm spring.” However, both Beijing and Tokyo are highly seasonal cities. If the analogies followed their natural course, the two countries would end up in icy winter again. The thorny, unresolved issues were festering. The foundations for the bilateral relationship had shifted. There was a generational change. Public opinion in both countries was tough on any perceived compromise, and the bruising diplomatic fights had weakened the position of the moderates in both countries. As figure 1 shows, an annual poll conducted by the Japanese prime minister’s cabinet office indicates that the Japanese sense of affinity for China has weakened dramatically from 1978. Japanese affinity stayed at a relatively high level until China’s Tiananmen crackdown on June 4, 1989. It then matched the percentage of no affinity in 1995. Public sentiment was largely negative in 2004, and continued to worsen; in 2015, 83.2 percent of those polled felt no affinity. There are no similar tracking polls on the Chinese side, but other polls reveal a similarly negative Chinese view of Japan. Strong negative public opinion would constrain the two governments’ ability to manage crises.

Initially, I believed that the Sino-Japanese relationship would continue to be more or less stable for a few more years. It appeared to me that both sides had learned a lesson from the relationship management from the past decade. On several occasions, one side was more conciliatory, which the other side mistakenly interpreted as proof of success of its own hardline response.

Then, on September 7, 2010, a Chinese fishing boat rammed into a Japanese coast guard ship that was chasing it in the waters close to the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu islands. This was an accident waiting to happen. The ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) had suffered a landslide defeat against the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) a year earlier. The DPJ government was more conciliatory than the LDP government over the historical apology issue, but took a strong position on the territorial dispute with China. This dispute had emerged as the biggest challenge to the bilateral relationship in the post-Koizumi days.

Living in Tokyo at the time, at first I did not expect the collision incident to become a crisis. There was already some sort of precedent that the Japanese government could follow: it could have asserted Japan’s sovereignty over the islands, and then fine and expel the Chinese captain. Yet as I followed how the DPJ government handled the incident, I quickly became pessimistic. The DPJ was scheduled to have its party presidential election on September 14. Kan Naoto, the sitting party president and prime minister, had held his prime ministerial position for only three months. He was challenged by a powerful politician, Ozawa Ichiro. Kan won the party election in the end, yet the DPJ lost in the larger scheme of things. One of the casualties was Japan’s relationship with China.

The DPJ government decided to try the Chinese captain according to the domestic law. Beijing saw that decision as Tokyo’s attempt to change the status quo of shelving the dispute that dated back to the 1972 normalization negotiations. Acting out of anger, the Chinese government adopted a series of punitive measures, including suspension of official dialogues and exports of rare earth metals. The Chinese captain was released on September 24.

The Chinese fishing boat collision incident was a landmark event. Since then, the Sino-Japanese relationship has been drastically different from before. Kan’s successor, Noda Yoshihiko, decided in late 2012 to “nationalize” the disputed islands by purchasing them from a private owner. The Chinese sent in government boats to regularly patrol the areas. The situation became very tense.

Shortly afterward, the DPJ lost to the LDP in a landslide election. A weak economy and a proposed consumption tax hike weighed heavily on voters’ mind. Yet the DPJ’s perceived weakness in dealing with Beijing was also important. Abe Shinzo came back as prime minister. This time around, he took a decisively different approach from his stint in 2006. The new Abe government was determined to be tough on China. Unlike the DPJ government, Abe’s government had revisionist views of history, which added to the tension with China considerably. In his LDP presidency election campaign, Abe expressed regret for not having visited Yasukuni Shrine as prime minister. He visited Yasukuni in December 2013, but since then he has refrained from repeating the visit, owing to strong international criticism. Official Sino-Japanese relations froze.

Two developments in Sino-Japanese relations since 2010 are particularly salient. Military conflict is now imaginable. Both the Japanese and Chinese governments have openly multilateralized their disputes, which makes them harder still to manage.

The official relationship has warmed a bit. Chinese president Xi Jinping and Prime Minister Abe met at the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in Beijing in November 2014. It was an awkward meeting, vividly captured on camera. However, it allowed the high-level official exchanges to resume. Some Western media again termed the Xi-Abe summit as “ice-breaking,” and yet the Sino-Japanese relationship is now in a different cycle from that between 2006 and 2010. The two countries remain set on a collision course. Nothing substantive has changed. Both sides are strengthening their military capabilities and readiness. The South China Sea has become a particular point of contention. Both sides are making diplomatic moves to check on each other. History is back on the diplomatic agenda. To a large extent, the two governments are resorting to kabuki-like theatrics with each other in their top-level dialogues. This is the best they can do at this point.

From the late 1990s to 2010, the Sino-Japanese relationship was unstable because the two sides could not agree on a new structure for the bilateral relationship.

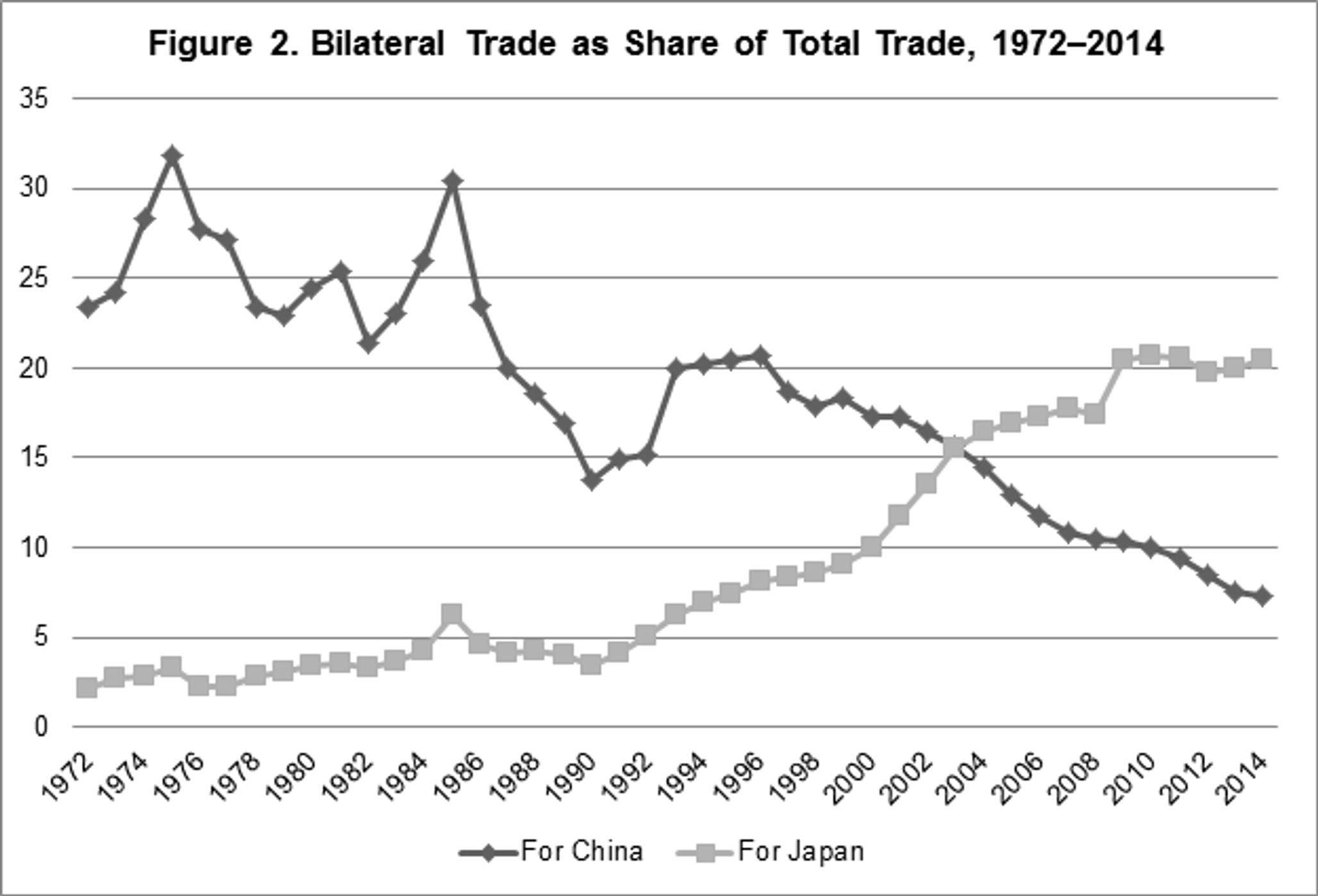

The confrontation between China and Japan could be far worse. They have restrained themselves because of the inherent danger in outright hostility and because they are woven in a web of economic and person-to-person ties. If we were to simply examine the flow of goods and people, we might as well conclude that the two countries are integrating with each other. Yet clashing national identities and material interests have more than offset the integrating potential of economic ties. Security concerns still trump economic calculations. At the same time, it would be wrong to ignore the long-term effect of economic and individual ties. China and Japan are important for each other economically, particularly for Japan. Based on data from the International Monetary Fund’s Direction of Trade Statistics Yearbook, figure 2 shows how Japan has become highly dependent on the Chinese market. This dependence has actually increased from the 2006–10 period to slightly over 20 percent of its total trade at present. In addition, Japan has been promoting tourism with China as the most important target source.

In short, the 1972 structure largely ended with the end of the Cold War. From the late 1990s to 2010, the Sino-Japanese relationship was unstable because the two sides could not agree on a new structure for the bilateral relationship. To be stable, a social structure has to be agreed upon and socialized. There were also real differences between the two countries. We now have a structure of animosity, in which both sides blame the other for tensions but nonetheless acknowledge their hostile rivalry. I cannot see any potential landmark event that may drastically change the dynamic in a positive direction for the foreseeable future.

The U.S. Factor in Sino-Japanese Relations

I deliberately avoided mentioning the United States in my previous discussion to make a point that not everything revolves around Washington. It follows then that it would not be particularly meaningful to debate “who lost the Sino-Japanese relationship?” At the same time, the United States has been the most important country influencing Sino-Japanese relations. The United States shapes the Sino-Japanese policy environment, and may even directly intervene in their relationship. One can and should integrate the United States fully into a discussion of Sino-Japanese relations. I also excluded the United States initially because I wanted to isolate the U.S. factor from China and Japan. In this section, I will put the Obama diplomacy in the historical context of American policy toward Sino-Japanese relations.

The United States decisively constrained Sino-Japanese relations between 1952 and 1972. Japan would have liked to normalize official relations with China, preferably in a two-China model that would acknowledge the existence of Taiwan. However, the United States would not allow it. Once President Richard Nixon made the first move, the Japanese moved fast to establish diplomatic ties with Beijing, and did so more than six years before Washington succeeded in doing so. Yet Japan’s diplomatic move was compatible with America’s anti-Soviet grand strategy and provided a model for handling the thorny Taiwan issue. Japan offered official development assistance to China starting in 1979. The United States could not do so because of the restrictions imposed by its own domestic laws. However, its acceptance of Japanese efforts toward China was consistent with Washington’s support for Deng Xiaoping’s reform and opening up policy.

Although the foundation of Sino-Japanese relations began shifting after the end of the Cold War, official Sino-Japanese relations were actually good in the early 1990s compared to the high tension in U.S.-China relations and the trade fights between the United States and Japan around the same time. Washington’s relations with both Beijing and Tokyo improved in the late 1990s. President Bill Clinton delinked human rights and trade in the mid-1990s. There was also a refocus on security cooperation in U.S.-Japan relations in the second term of the Clinton presidency. This took on greater significance after the tensions in the Taiwan Strait in 1995 and 1996. The United States exerted a powerful structural impact on Sino-Japanese relations. China and Japan each found the United States to be a more attractive partner than the other. The United States had a long-lasting alliance with Japan, reinforced by a shared democratic system and increasingly convergent strategic interests. At the same time, the U.S. military presence in Asia mitigated the need for Japan to beef up its military. This was reassuring for China. The Chinese economy began to take off in the early 1990s, and its economic growth eventually allowed it to surpass Japan in terms of gross domestic product and to become a near-competitor with the United States.

The mid-air collision of the U.S. Navy EP-3 surveillance plane and a Chinese naval fighter jet near China’s Hainan Island on April 1, 2001, led to increased tensions and expectations of more virulent confrontations in the future. This was the first foreign policy crisis for George W. Bush, who had become president only ten weeks earlier. However, the terrorist attacks on American soil on September 11, 2001, ushered in an ongoing war on terror and distracted the United States from conflicts in East Asia.

The Sino-Japanese fight over historical revisionism in 2002–6 was inconvenient for the United States, but was not yet dangerous. Japanese revisionist views caused a backlash in the United States as well. More than any other American foreign war, the American people consider World War II, which destroyed German fascism and Japanese militarism, a “good war.” The U.S. government preferred that the Japanese government own up to Japan’s dark past. However, the White House largely refrained from direct intervention that might facilitate Sino-Japanese historical reconciliation. Bush in particular had a strong personal relationship with Koizumi. The United States was supportive of an improved Sino-Japanese relationship in 2006–10; as a hegemon, it has a strategic interest in maintaining stability unless it itself has reason to confront another country.

Much of the world criticized the diplomacy of the Bush administration before and during the invasion of Iraq in 2004. Yet Bush’s performance in the Asia-Pacific region received good marks from commentators. Among other things, Bush improved U.S. relations with regional powers like China, Japan, India, South Korea, and the ASEAN simultaneously. Looking back, the United States acted with prudence in Asia. It was a stabilizing force in the region after the end of the Cold War. It helped that the United States had a stable presidential leadership. There have been only three presidents since January 1993. By contrast, there have been 14 Japanese prime ministers (with Abe serving twice) since August 1993.

Barack Obama assumed the presidency during a mini-honeymoon period in Sino-Japanese relations. His team was determined to avoid the pattern of early tensions followed by stability in the previous presidents’ dealing with China. He personally cultivated relations with the Chinese leaders, particularly Xi Jinping. However, the Obama presidency began during the Great Recession, which was viewed widely as weakening the United States at a time when China was on the rise.

Obama is determined to maintain U.S. leadership in the Asia-Pacific region. He has had a clear strategy. People differ only how committed he has been or how much tougher he should be on China. Facing both the Great Recession and the longest war in U.S. history, Obama wanted to rebuild the U.S. economy and pull out of the quagmire in the Middle East and central Asia to shift the U.S. focus to the booming Asia-Pacific. Initially dubbed the “pivot” by his then–secretary of state, Hillary Clinton, the Obama administration adopted a two-prong strategy of shoring up alliances and friendships and forming a high-standard Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement. Both policies aimed at shaping the environment facing China and channeling it in a direction desirable for the United States.

Obama was a symbol of change. Change was in the air in Japan as well. On August 30, 2009, the DPJ won a landslide victory in the general election of the House of Representatives. Hatoyama Yukio became Japan’s new prime minister. Hatoyama championed the creation of the “East Asian community,” which apparently excluded the United States. He also promised to voters that he would move the American Marine Corps air station in Futenma out of Okinawa. His pro-Beijing approach caused concern in the United States and in Japan as well. American distrust of Hatoyama gave a powerful weapon to his domestic political foes, and was a factor in his quick downfall less than a year later. Hatoyama’s DPJ successors would strengthen the alliance with the United States and moved closer to formally joining the TPP negotiations.

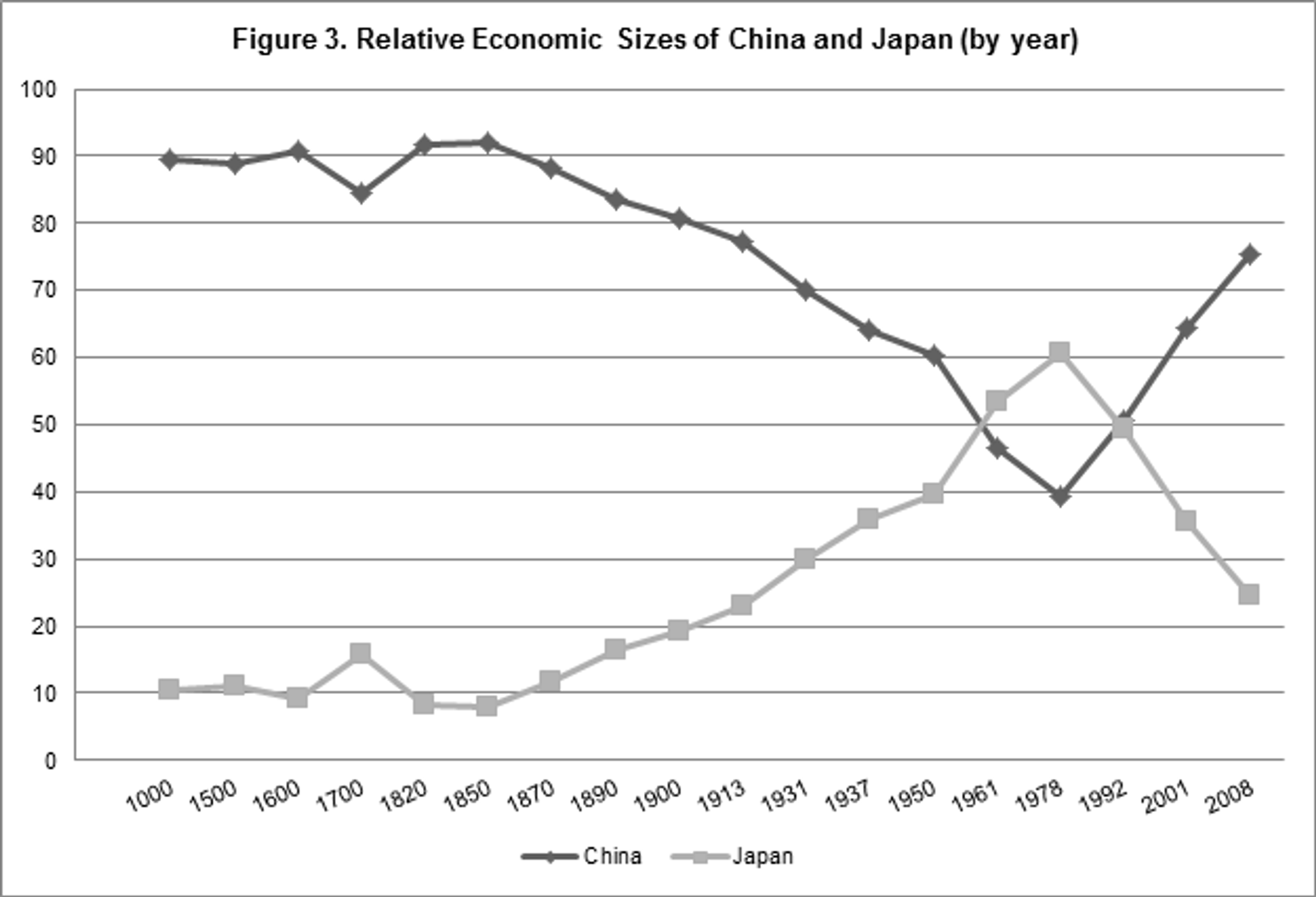

Obama declared end of war in Iraq in October 2013. The competition with China has intensified. The United States and Japan need each other more than before. As figure 3 shows, using data from Angus Maddison’s “Historical Statistics of the World Economy” database, the long-term trend in balance of power between China and Japan is not favorable to Japan. Recent disputes have made that long-term trend unbearable for the Japanese. Although the Japanese were worried mainly about entanglement in a potential U.S.-China conflict in the past, they are focused now on entrapping the United States into conflicts in Asia aimed at China. The Japanese would do whatever is necessary to make that happen.

The post-2010 Sino-Japanese tension largely has been about territorial disputes and regional leadership, both affecting the United States profoundly. The strategic interests of the United States and Japan now overlap more than ever. At the same time, the two countries still have divergent priorities. The United States and China do not have direct disputes over history or territories, which dominate in Sino-Japanese relations. That basic fact provides some room for compromise, particularly over larger global issues. As a case in point, the United Nations Climate Change Conference held in Copenhagen in December 2009 was often viewed as the start of the new round of U.S.-China tensions, because the Chinese delegates were said to have been rude to Obama. Yet Obama and Xi have been cooperating over climate change. A surprise agreement between the two countries announced in November 2014 helped anchor Obama’s strategy for the November/December 2016 climate change summit in Paris and showcased the positive consequences of U.S.-China cooperation. Moreover, the United States cannot simply pull out of the mess in the Middle East and Afghanistan. Obama bravely completed his planned visit to Asia in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks in Paris in November 2015, but U.S. media remained focused on the rise of the Islamic State, other fundamental Islamic militant groups, and Syrian refugees.

Obama has received strong criticism from the Republican presidential candidates. Hillary Clinton, the leading Democratic presidential candidate and Obama’s former secretary of state, has also distanced herself from Obama’s TPP initiative. At the same time, I doubt that the next American president, whether Democratic or Republican, realistically can do much better than Obama in the Asia-Pacific. Fundamentally, it is in the long-term interest of the United States to put more energy on domestic challenges. A strong economy, vibrant democracy, and a general consensus on foreign policy are the foundation of effective foreign policy. Like Obama and his predecessors, it would make sense for the next American president to combine cooperation and toughness in the Asia-Pacific region. China, Japan, and other Asian countries all cooperate where they can and fight where they must. The United States needs to put its own interests first, maintain its strategic maneuverability, keep calm and engaged, and continue to be pragmatic about a region in flux. East Asian international relations are a long and complex game.

* * *

Ming Wan is professor and associate dean at the School of Policy, Government, and International Affairs at George Mason University. His recent books include Understanding Japan-China Relations: Theories and Issues and The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank: The Construction of Power and the Struggle for the East Asian International Order.

Cover photo courtesy of Reuters/Kim Kyung-Hoon