Spring 2021

A COVID Winter: Arizona

– Richard Byrne

Conversations with Saskia Popescu: Epidemiologist and Science Communicator

The Wilson Quarterly spoke with a number of those involved in battling COVID-19 or covering its impact through a dark and challenging winter. Saskia Popescu spoke with Richard Byrne.

Saskia Popescu’s emergence as a go-to voice on COVID-19 is no accident. As a prominent researcher and practitioner in the fields of epidemiology, infection prevention and biodefense, she was prepared to weigh in with authority on the immense challenges posed by the global pandemic.

Popescu holds three academic appointments – George Mason University, the University of Arizona, and Georgetown University – and consults with a variety of governments and institutions, including the World Health Organization. She is also a member of the Federation of American Scientists’ Coronavirus Task Force, and the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine’s Committee on Data Needs to Monitor Evolution of SARS-CoV-2.

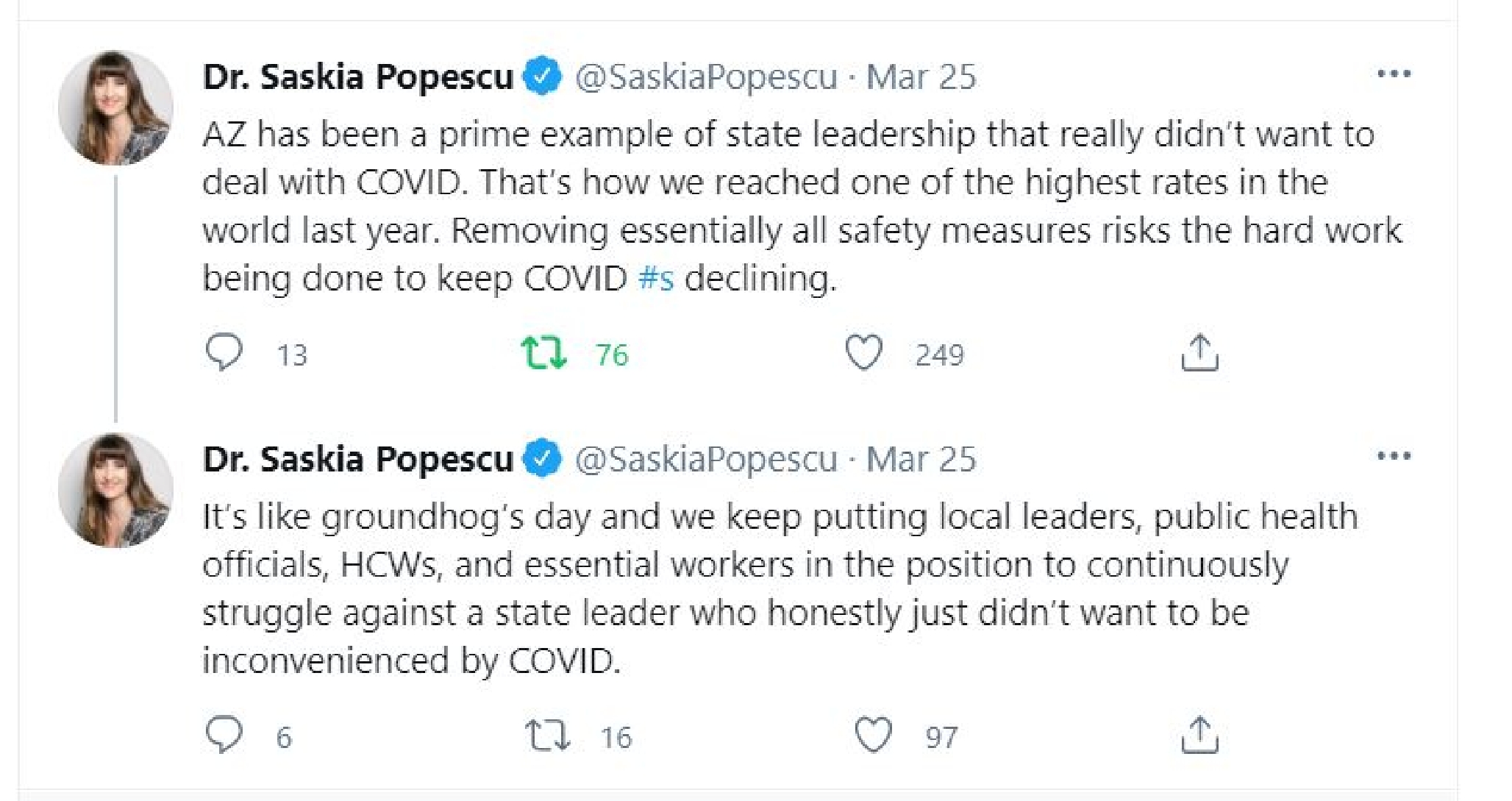

Yet it is her talents as a science communicator that have elevated her to greater prominence in this global pandemic. Whether it is as a source for journalists, or on her own Twitter account, Popescu tackles difficult science with clarity and rigor – as well as a talent for finding humor in grim circumstances.

It is a turbulent moment for public health, with increasing fractiousness in professional exchanges. But the audience for Popescu’s words – which often cut through the static with abundant common sense and humanity – is growing by leaps and bounds.

Walking the Talk (November 2020)

Pandemic holidays pose a conundrum. Even for epidemiologists. Popescu says that she and her husband will be splitting them up – one holiday with her family, and one holiday with his clan – as case counts rise across the country.

She says pondering how the average person copes with balancing between family togetherness and safety brings the challenges of following best practices to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2 into sharper focus.

“A lot of people who work in healthcare or infectious disease are so risk-aware in our work areas,” says Popescu, “and then we get super relaxed elsewhere…. So it was really important to me, when we were starting to see things bubble up. This is not the time for that attitude.”

Walking the talk is essential. “We spend a lot of time… talking to people about how they can be safe. But then we aren't doing it ourselves,” observes Popescu. “Like if I can't do it. I don't expect anybody else to do it, right? Because, in theory, infectious disease people and infection preventionists should be the best at doing quarantine and all of those things, But we're all human, right? So that for me was one of the biggest pieces as I was looking at the holidays. What am I sharing with people, and is it something that I can follow? Let alone them.”

She adds that a lack of clear national leadership isn’t helping – not only to forge unity amongst Americans as pandemic intensifies, but also to reduce the political and public health burdens placed on state and local authorities.

“That’s not something we've discussed enough,” Popescu observes. “I don't like saying we have 50 different outbreaks. I think we have a giant one, and everyone's just responding to it in different ways. And some are doing better than others. But you know when you have [an] absent national approach... It puts a lot of onus on local leadership… but ultimately not everybody is built to respond to something like this.”

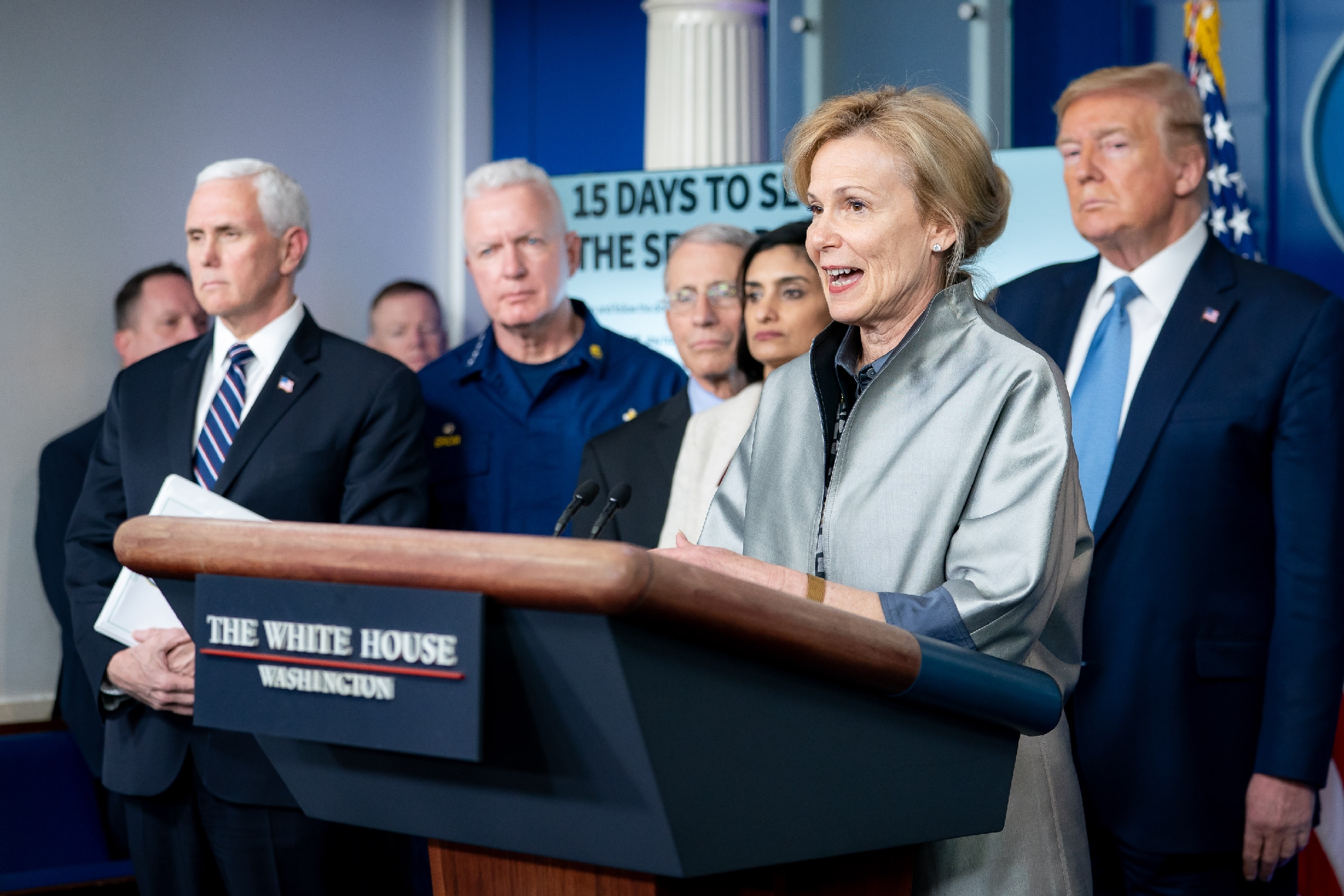

Actions taken by the Trump Administration, even prior to COVID-19, such as ending the National Security Council’s directorate for global health and security and bio-defense in 2018, set the stage for the predicament that government found itself as pandemic swept the nation.

“I think pretty much anybody working in infectious disease and pandemic preparedness knew that if we had a biological event under this administration, it was going to be bad,” says Popescu. “But I don't think anybody predicted how bad it would be. Simply put, that's just not something that they prepare you for in school. In [pandemic] response, there's kind of this assumption – and clearly it was a wrong one – that you'll have a certain amount of support and a national approach. That we'll be doing something, and not just giving it the old college try, and effectively washing their hands of it.”

Popescu notes that the way that partisanship seeped into public health attitudes is perhaps the most disconcerting element of the U.S. response: “To see the utter politicization of basic infection prevention and response – people making masks a political statement – is just mind-blowing to me.”

Finding a Space (December 2020)

On the cusp of a new year, after six weeks of staggering numbers of cases, hospitalizations and deaths, Popescu is working on a number of aspects of pandemic response. Some of her work is on something very basic, yet much misunderstood: masks.

“We are definitely cognizant that not all [masks] are created equal,” she says. While masks do need multiple layers and closely knitted fabrics, what’s also missing is public awareness that fit is as crucial as material.

“Some people will be really wonderful about getting a mask that has multiple layers and all those features,” she continues, “but not necessarily well fitting.… It’s hard because I still see a lot of people wanting N95[masks], and…it’s not something that’s been readily an option for the public. It carries with it a lot of caveats for efficacy, like fit.”

.jpg)

The complexities lurking in communicating about something as simple as masks are a challenge for Popescu and other experts – especially as Americans (including Twitter followers) desperately seek certainty.

“Science communication is easily one of the most challenging things that we do,” observes Popescu. “I'm constantly in a state of learning, you know…. None of us are perfect.” On reflection, she admits that “the biggest failure we probably made early on was being so certain about things, and not saying like this is going to change. So be prepared for that.”

Immense public interest has created a bull market for expertise – real and imagined. A multiplicity of voices now vie for attention in the marketplace of pandemic ideas. Suddenly, veteran researchers who worked in epidemiology and infectious disease long before COVID-19 emerged find themselves confronted by what Popescu calls “a huge wave of armchair epidemiologists, or people who feel the need to insert themselves into the conversation because of their background.”

Popescu believes some newly-minted experts are “taking advantage of the situation, and [have] used it to monetize themselves – for attention, for followers, for whatever it might be. And that's really damaging to science communication.” And the stakes are higher than mere academic turf.

“To see the utter politicization of basic infection prevention and response – people making masks a political statement – is just mind-blowing to me.”

“It's not because it's gatekeeping,” continues Popescu. “It's because there are serious implications for the things that get said. When suddenly you have somebody who only specializes in geographical data speaking about school reopenings, that's a huge red flag for a lot of people.”

Battles over science expertise can be ferocious, and even become abusive – especially for women scientists on Twitter. “It's super weird,” says Popescu. “Like a hundred percent. I didn't really ever pay attention to followers.” When her numbers skyrocketed, she adds, it was “really weird to me, because I'm just like super nerdy and awkward and weird.”

Twitter has become an essential space for science communication, but being a woman offering genuine expertise on the platform remains vexing. “Sometimes I have just felt very frustrated with it,” she continues, “because I've noticed that women – when we push back or call out false experts or sensationalism – get called 'shrill' or 'petty'…. It's been really shocking sometimes. I am constantly having to defend my expertise or my skills and my knowledge against people who really have never even talked about this stuff before this year.”

And the actual abuse to which she is subjected on Twitter? “It's continuous. Especially as a woman. It’s just gross.”

Being an expert in a moment of crisis offers an additional challenge as well: Finding the “off” switch.

“I can't even describe how burnt out we are,” says Popescu. A conversation with fellow researchers led to commiserations about “entire days talking COVID, working COVID, doing interviews on COVID.”

“And then, on the off chance,” she concludes, “you may be like seeing a neighbor from across the street, or [be on] a family Zoom, and all they want to do is ask you about COVID.”

The desire to offer good advice and reassurance usually wins out, but Popescu says that “the hardest part is carving out mental space for yourself.”

Getting to Tomorrow (January 2021)

Even a few days later, the inauguration of President Joseph Biden on January 20, 2021 appears to be a crucial moment in the U.S. battle against COVID-19.

“I think everyone is very optimistic about the changes in national leadership,” says Popescu in a late January conversation. “They are very pro-science and approaching COVID [with] a holistic lens. They are being mindful of the health disparities that exist, and the economic support that's needed for everything from genomic testing to vaccine distribution.”

Yet there are significant hurdles as well. Horrific statistics and the global emergence of new COVID-19 variants are only the start. For science communicators, a key question is: What should researchers and public health officials be saying right now?

“It's a very challenging time,” she continues. “We’re really trying to understand what it means for our protocols and the things we have in place. Being mindful that this is a time where we're getting new information. How do we disseminate that to the public?”

Another problem? Some issues much on Popescu’s mind last month seem only to have intensified: “I think everybody is just so collectively exhausted. I personally have seen in the month of January more burnout and fatigue [in] a lot of the people I know and I work with – and whom I'm even friends with – in the field. And it seems like there's a lot more vitriol online too.”

The past few months' surge in cases and fatalities have Popescu questioning the basic effectiveness of current methods of communicating key information: “When I see some of these events occurring, I'm also [thinking]: Did we give people all the tools and education to be successful? I try to come at it from that standpoint, because I don't think we've always been successful at making sure people understood why they shouldn't be doing something. You know, it's not just a matter of saying you can’t build igloos outside [for dining], but explain the process.”

Those who work in public health, preparedness, and response must always look forward. Yet right now, quips Popescu, “looking forward is, like: ‘Oh God, we just have to get to tomorrow.’”

"It's been really shocking sometimes. I am constantly having to defend my expertise or my skills and my knowledge against people who really have never even talked about this stuff before this year.”

Yet she knows that pondering the future is important. “One of the things that we’re increasingly having conversations about is: What does de-escalation look like? What does that mean? Because it's so varied across the U.S.,” says Popescu. “And, as we look to hopefully get a large percentage of the U.S. population vaccinated, and as control measures are working… so the case counts are really low, what is [de-escalation]?”

In the darkness of mid-winter, Popescu sees hope. “It's a very, very exciting time,” she says. “But I think we're also trying to be…. reasonable with our expectations. Because, you know, nobody wants to be disappointed. We just need to be pretty frank and upfront about [the fact that] this is going to take a while.”

No On/Off Switch (February 2021)

Late in February, Popescu still feels optimism.

“The data's all trending in a really great direction,” she observes. “Vaccine availability is growing. And I think we're really doing a lot of good work around vaccine hesitancy, which is helpful.”

Yet the caveats remain. Will difficult lessons of the summer and the dark winter be forgotten on the verge of spring?

“There's light at the end of the tunnel, essentially,” says Popescu. “But with new variants, and a very American habit of prematurely opening things back up, and going from zero to sixty, it's also one of those times we’re really trying to remind people that we still need to stay home and avoid indoor activities with people outside of our household. It's a challenging time, because you're trying to mix hope and a lot of really optimistic data and trends with the recognition that this is not over. We still have a lot of work to be done.”

The earliest green shoots of recovery have people thinking about next steps. Yet as an epidemiologist, Popescu is alert to issues of public health preparedness, public consensus, and equity as she ticks off a number of them. It might not be time just yet.

While vaccine hesitancy is not widespread, for instance, the societal implications of vaccinations remain fuzzy. Can your employer require you to get one? “I think it's hard because, right now, they are all under [emergency use authorization],” she remarks. “When that does change, then I think you'll likely see more employers making it required.”

Vaccine passports? “I think that will change the game a little bit,” says Popescu. “But for the most part, immunity passports are not something that we really want to emphasize. [They] create a disparity and an equity issue.”

Such questions are natural, but Popescu feels they glide too easily past the global challenges that will shape how we will live with COVID-19 for years to come.

“What I struggle with right now in having those conversations is that people say: “Well, when can I start traveling again? When will it go back to normal? We forget the global health piece to this. Vaccine equity is a really big problem right now, and it feels very American-centric to say: ‘Well, when can I go do this?’… I really hope that we start to look at this as a global health issue.”

What might shift the discussion in a better direction? Perhaps the all-encompassing nature of this pandemic. Popescu argues that some U.S. lack of preparedness is due to the fact that Ebola and H1N1 “were not as hard felt in the United States. So, to a certain extent, once public attention dwindled, you saw support for funding and resources dwindle too.” Perhaps, she continues, “because this has been such an impacting event, we won't let it happen again. We will demand changes.”

Popescu adds that shifts in U.S. attitudes on basic things since the start of the Biden administration are heartening – and a turn in the right direction: “It's now like you're not the odd person out wearing masks,” she observes. “I am hoping that will kind of stick moving forward. You're going to see people wearing masks the entire flight. And at the doctor’s office, honestly, I'm all for that. Normalizing that behavior is important.”

The urge to relax as winter nears its end is natural, says Popescu. “We're not quite there yet. Where we can just totally relax everything. It's not going to be a binary. An on-off switch. It's going to be a little bit of a dimmer when it comes to relaxation of restrictions.”

Two Fires (March 2021)

As March turns to April, Popescu is heartened by watching vaccination rates surge upward. But she is cautious, too.

“We've really struggled when the finish line is in sight to not just totally fall apart,” she remarks.

A clear pathway to a break in the pandemic’s intensity after more than year should be a clarifying moment. But Popescu says the job for science communicators won’t be any less challenging.

“[COVID-19] is nuanced, right? And we are learning as we go,” she says. “Modifying as we go.”

The kaleidoscopic nature of how research flows into policy, as well as the cacophony of voices in media outlets, make it hard to find solid ground. Outdated protocols, pseudoscience, bad advice and magical thinking abound – much of it dispensed with a scientific veneer.

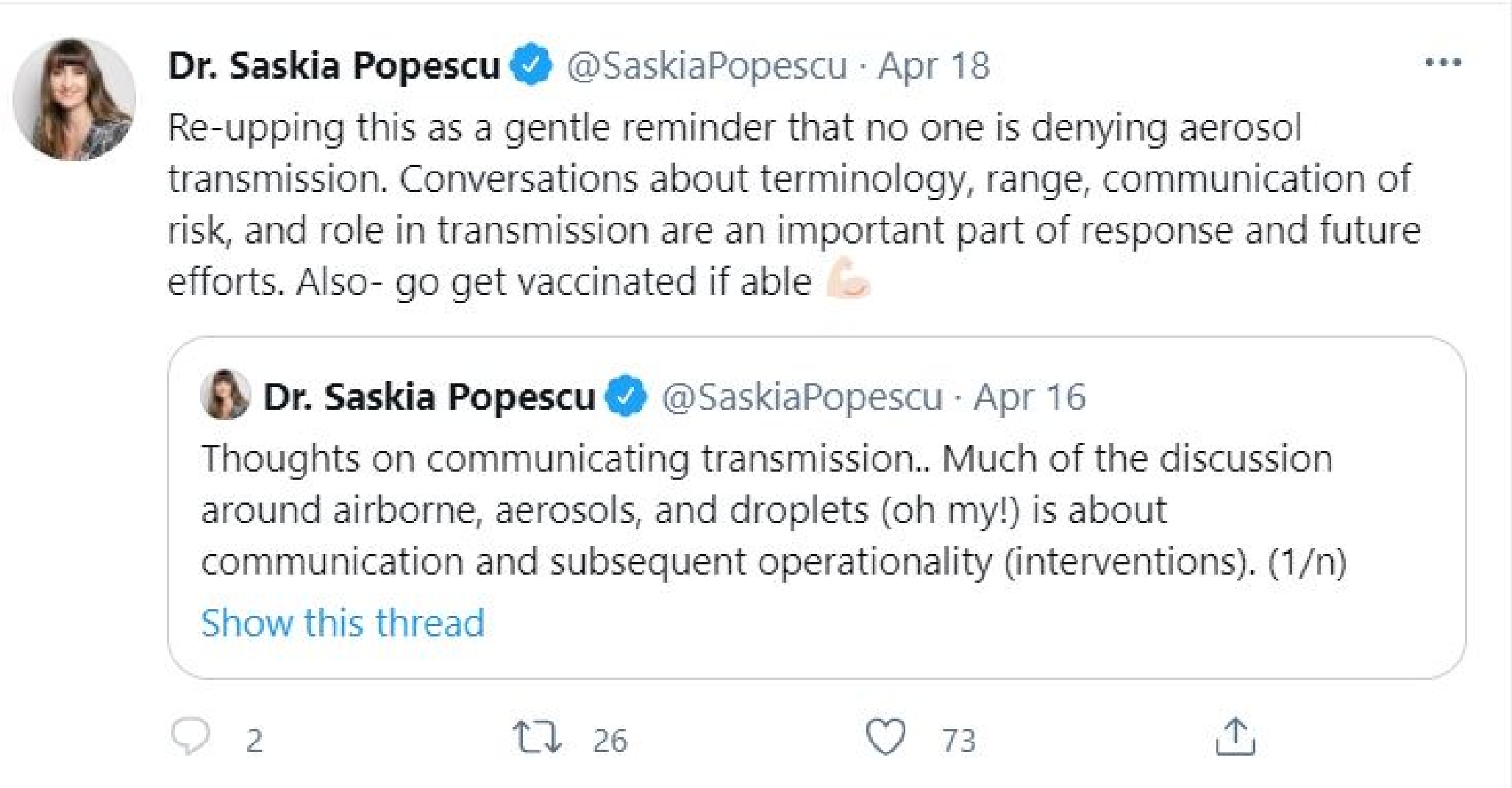

“There has been a lot of concern from those working in public health,” says Popescu, “that we're having to spend as much time combating misinformation as we are sharing correct messaging.”

Popescu breaks down a particularly fraught bit of terminology – airborne transmission – as an example. “Long-range aerosol transmission, often referred to as airborne, [of COVID-19] can and does happen - but it’s not the only route of transmission. It also has a very specific meaning in public health and infection prevention, and really I think this has shown that disease transmission is a spectrum and not a dichotomy, meaning it needs more work on communicating and interventions."

The problem, says Popescu, comes in “explaining the nuance of that. Because it's not a dichotomy. It's not either/or.”

Fomite transmission of COVID-19 poses similar challenges. “That is a little bit less nuanced, but that's been a hard piece [to communicate]. Explaining to people that this isn't as high a risk, but it's still a possibility.”

"It's not going to be a binary. An on-off switch. It's going to be a little bit of a dimmer when it comes to relaxation of [COVID-19] restrictions.”

Fractious debates over whether there is too much attention to surface cleaning are more damaging than helpful. “Fomite transmission is lower risk, but you should still be washing your hands and cleaning things as part of a full prevention package,” she observes. “And that includes wearing your mask, and distancing, and being mindful of ventilation and crowds.”

The present may be contested. But the end of a long COVID-19 winter has Popescu focused on the long game in battling the pandemic and navigating its immediate aftermath.

“COVID is likely going to be endemic for a while,” she says. “I don't believe in zero COVID. I think that's a wonderful national approach for some countries. But this is not a disease that we're going to be eradicating any time soon, especially when you look at global vaccination rates and distribution…. COVID is a huge example of something where there is an immediate threat, but then also the long threat. Things like Long COVID.”

“We are very focused on putting out the most immediate fire. But, in this case, we have to have near sight and far sightedness. To the long game. And I think that's the thing that we've really struggled with in the United States.”

Richard Byrne is the editor of The Wilson Quarterly.

Cover Photograph: Phoenix, Arizona at night. ( piotr beym / Shutterstock)