Spring 2021

A COVID Winter: Washington, DC

– Alex Long

Conversations with Jourdan Bennett-Begaye: Managing Editor, Indian Country Today

The Wilson Quarterly spoke with a number of those involved in battling COVID-19 or covering its impact through a dark and challenging winter. Jourdan Bennett-Begaye spoke with Alex Long.

Stepping Up (December 2020)

COVID-19 is a global crisis. But as the Washington Editor for the publication, Indian Country Today, Jourdan Bennett-Begaye has felt responsible for tracking its devastating ripples in her own community.

“We were just trying to keep an eye on all of Indian country,” Bennett-Begaye recalls, “to see where the first case would pop up. Our whole team is connected on social media, and all of us come from different communities. I'm Navajo, but we have a Pueblo on our team. Mark, our editor, is Shoshone-Bannock in Idaho. We have a couple of Ojibwes from different bands up North.”

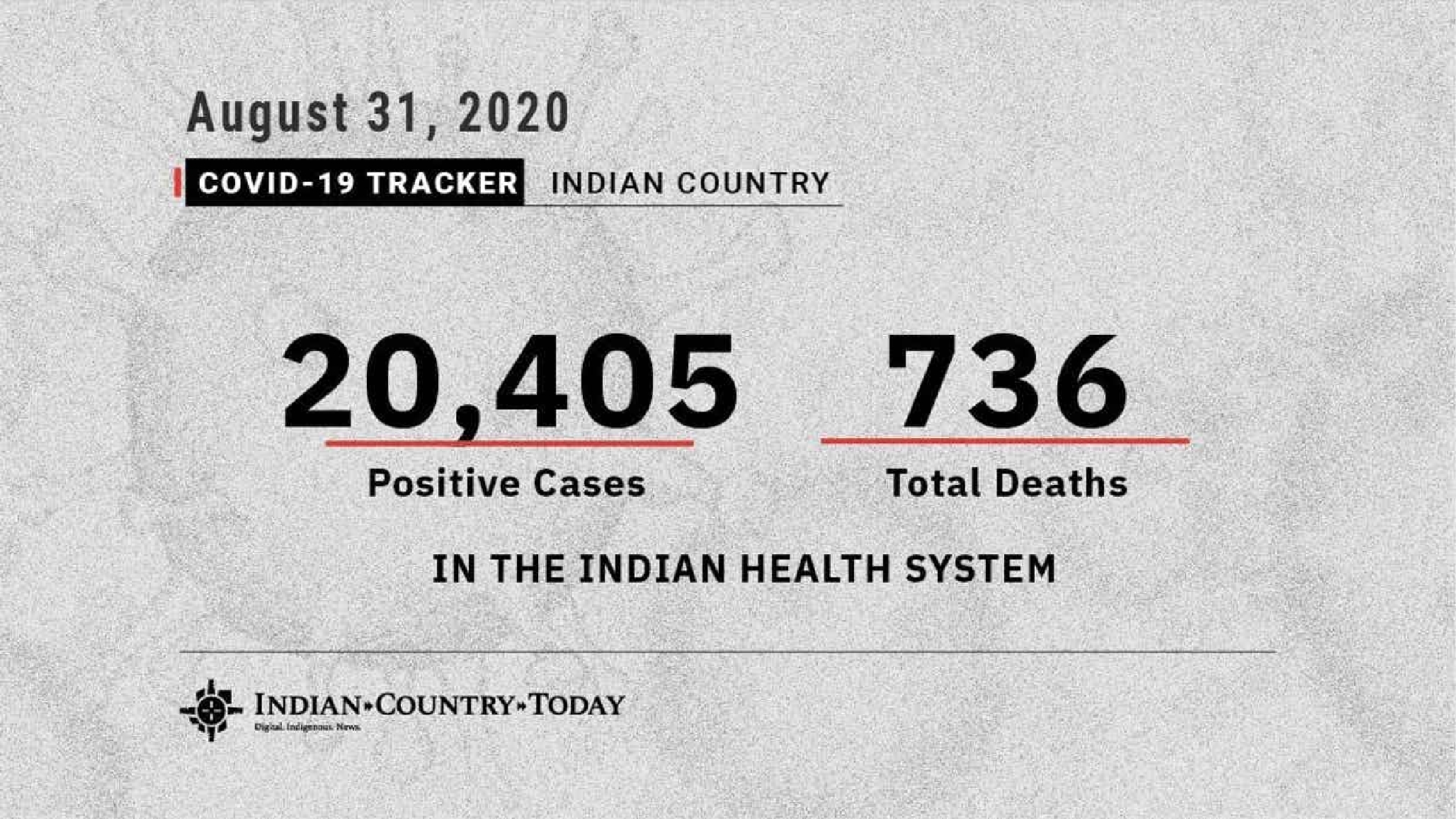

Data was essential to tell that story, even if it was hard to come by. She consulted Indian Health Service (IHS) updates but found the figures were inconsistent and not updated daily. Being in the dark about COVID-19’s impact bothered her and others. “People were wondering on my Facebook feed. I could see that they wanted to know how many cases their tribe had.”

Bennett-Begaye decided to compile this essential data herself. She began calling tribal clinics and health care centers one by one, asking for data on COVID-19 cases and deaths. The result was a website, Indian Country Today's COVID-19 Syllabus, as well as an open database.

“I just had this like wild idea," she continues, "once more [cases] started coming: ‘Oh, it'd be pretty cool to see what would happen if we tracked it. Maybe this could be something we could use.’ I didn't think about sharing it publicly, until I had about maybe seven cases in there.”

State and county data were difficult to obtain at first, but it improved steadily as months unfolded. In Native communities, however, mechanisms to obtain and process reliable data are underfunded by the federal government and other entities, leaving tribally-run health clinics and sites controlled by the IHS unable to easily share data.

And to make the job even more difficult, trust proved to be in as short supply as funding. “We have a trust issue, right? Because the federal government betrayed us,” observes Bennett-Begaye. “So there's definitely that trust that you have to get through. It's so difficult. Even as a Navajo woman, it's difficult… they kind of trust you, but they still don't trust you.”

The database’s open format helped it gain currency, and allowed Bennett-Begaye to tell tribes and community leaders that “we are open to criticism and we are open to feedback as well.”

People started to pay attention. According to a UCLA study based solely on Indian Country Today’s database, the reporting tool captured data and regular reporting from 287 of the 574 federally recognized tribes. It was a huge feat, especially considering that no one else was doing this work.

The data project offered Bennett-Begaye a window into the severe costs that COVID-19 was exacting from Native communities. “I just saw the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara tribes (also known as the three affiliated tribes) had a jump: from a 130ish cases [at the] end of August to [699 cases at the] end of November… That's a huge jump.”

Bennett-Begaye’s database project caught the eye of the COVID-19 mapping team in charge of the Johns Hopkins University (JHU) map. After Hopkins began partnering with the publication, 30 volunteers were recruited to “go out to all these tribes, call them, email them, figure out if there is a place like a website or social media where they could get their link to put in this algorithm. And then it would update a spreadsheet every single day.”

The data project offered Bennett-Begaye a window into the severe costs that COVID-19 was exacting from Native communities.

The database was featured on NPR’s science podcast ShortWave. And it was part of successful work that has led already to her promotion to Deputy Managing Editor of Indian Country Today.

“I'm now one of the decision-makers,” she says, “and I feel I have responsibility as a young person, to step up and, you know, figure out who I am as a leader, as an editor.”

Chronicling a Crisis (December 18, 2020)

News doesn’t stop because there is a pandemic. As the Deputy Managing Editor of the publication of record of Native lands, Bennett-Begaye must find a place for news other than the pandemic:

“I think the first few months… all the newsrooms [were] asking [COVID-19] questions…. All of a sudden, other news [was] passing us by….There was the Mashpee Wampanoag land dispute that we caught on our radar. And we were like: ‘Oh, we need to do something.’”

For instance, the announcement of Rep. Deb Haaland’s nomination as President Joseph Biden’s Secretary of the Interior was big news for Indian Country Today. Speculation that Haaland would be the first Indigenous woman tapped for a cabinet position was at fever pitch, and the publication readied its story days before the announcement broke via a tweet from The Washington Post.

Indeed, the Indian County Today team was so prepared that they had their stories about Haaland up in four minutes. “I really wish we had it in two, but it's okay,” quips Bennett-Begaye. But she does wish that her publication - or any Native publication - had broken the story.

“We try to keep in mind that Native people aren't used to having Indigenous media that represents them,” she says. “I think that's [something] that they have to get used to – and we've got to keep our head down and keep grinding. One day, it'll happen [and we’ll get the scoop].”

Not that Haaland’s achievement wasn’t a motivating moment for her as well. “I really like how Nick Tilson, the CEO of Indian Collective, put it: A Native woman representing and leading a department that was responsible for the exploitation of native people. I thought that was just very chilling and true.”

A flood of other news that Native audiences need to know also makes it harder to keep a focus on the COVID-19 database – especially at a small organization like Indian Country Today.

“With the Deb Haaland news, and with so much happening this year, I haven’t been able to update our database with the death toll,” says Bennett-Begaye. “But it's climbing up there. I guarantee it. There's probably more than maybe close to like 2,000 deaths that we're not catching due to the lack of data. We’re trying our best. We have our small team. But we're trying to do our best to capture it and see the big picture of it all.”

History records that the 1918 Flu Pandemic ravaged Native communities, yet there is relatively little documentation on the depth of loss in tribal nations. The duty to chronicle 2020’s crisis is at the top of Bennett-Begaye’s mind.

“I think it's really important for us to document the stories that are happening – and to not have our people be another number, another statistic, or another asterisk in the data, right?... I think our job is to make people not feel invisible, to make them feel seen and heard…because you know, the people who are dying every day, in tribal nations are people who are loved. People who are aunts, uncles, moms, dads. They matter just as any other person, any other white person who's dying too.”

Bennett-Begaye lost her cheii (“maternal grandfather” in Navajo) in the pandemic. “It's hitting my own tribe really hard,” she observes. “That's why I came home.”

She recalls how her cheii used to go get the mail, an activity that ceased when the pandemic took hold. “He would dress to his best every day, and at 9:45 [or] 9:50, he’d go drive to the mail in his boots, his nice jeans ironed, his button up shirt, ironed, his cowboy hat, and his nice watch. It was just so neat to see that every day.”

Bennett-Begaye recalls her cheii as “a quiet guy. So, I don't know if he talked to people. But some social interaction was very helpful. To go out and about. When the pandemic hit, it cut off all social contact and movement. And I think that really took a toll on him. I know that's what a lot of people are saying across the country. The isolation has taken a huge hit on the elders.”

Testing and Trial (January 7, 2021)

Bennett-Begaye was in line for a COVID-19 test when an insurrection aimed at stopping the count of the Electoral College swept through the U.S. Capitol.

The assault on the Congress began as she and her sister were driving to a testing site. “I was like, ‘Oh my gosh.’ I was using my hotspot on my laptop, trying to be on phone calls,” she recalls. “‘We're okay if we can do a phone call in five minutes. Hold on. Let me just get the swab of my nose.’”

Warm Hands (January 22, 2021)

The inauguration of President Joe Biden was a signal event for Bennett-Begaye, especially since she was preparing for yet another promotion, this time to Managing Editor.

“I've been obsessed with U.S. presidents since the fifth grade... So, to actually be there and witness it: The little girl inside me was so amazed,” Bennett-Begaye says. And while she did take precautions for an event with a heavy security presence and a threat of violence, the main struggle turned out to be “just trying to keep warm, and keep my hands warm so I could type.”

Indian Country Today’s statistical database has also been on Bennett-Begaye’s mind, as its recent effectiveness was slightly hampered by a lack of volunteers and cash. “This project is really not funded,” she admits. “So it falls to the bottom of everyone's list, even though it's a very important one.”

Yet there are glimmers of progress as well. She observes that because Facebook is a key hub of communication for all things Indian Country, engineers were deploying data scraping algorithms to comb through social media posts and data for tribal updates on cases and deaths.

“From the dirty laundry to anything informational,” she says, “you're going to hear about anything and everything [on Facebook].”

Indigenize the Narratives (February 4, 2021)

Her new job as Managing Editor has provided Bennett-Begaye with a chance to reflect on her own trajectory. Managing a staff, battling burnout, and getting readers the news they need is essential. But fulfilling her own publication’s mandate to serve Indigenous peoples is also on her mind.

“I feel like journalism was made for the dominant culture,” she says. “For white men. They created it. And it wasn't made for Indigenous people. We were already storytellers, but I think this industry really didn't have a place for us – so we had to go in there and create our own space.”

Her goal isn’t merely to tell the stories of Native peoples, but tell them with nuance or, as she puts it, to “indigenize” the narratives. “I think that's what makes our organization so key in telling stories about Native people and Native issues,” she continues. “Because it is so complex. I don't think a lot of non-Native or even like niche journalists understand that…they think it's easy, but, no, it's, it's really not.”

Vaccine distribution and adoption in Native populations is a good example. Historically justified distrust in the medical establishment in Indigenous communities (ranging from forced sterilization to a tragic underfunding of IHS) would be cause to anticipate vaccine hesitancy.

But such fears were dispelled as more data came to light. A new study had revealed that vaccine hesitancy was shockingly low compared to the general public. Tribal nations were leading the charge in U.S. vaccination.

This good news on vaccines was also personal for Bennett-Begaye. She was still waiting on her own vaccination, as an urban Native, in the Washington DC metro area. But by mid-February, she happily observes that “my whole family, my mom, my dad, [my older sister, my younger sister], my extended family [are] all vaccinated at least with their first dose.”

Irreplaceable Losses (March 4, 2021)

Reflecting on a year of pandemic, Bennett-Begaye recalls the first moment when the reality broke into her consciousness:

“I think I recorded ten deaths in one sitting. And that's when I was like: ‘Wow, this is really happening.’ I just had to kind of process it. And my eyes started watering, and my partner at the time was here, and I was just starting to cry. I went to the bedroom and I was crying. I remember calling my father and telling him, ‘Dad, take it seriously. I cannot lose another person I love. I cannot do it.’”

She adds that losses go way beyond a personal impact: “The people who are dying are elders, and for Native people, that is our culture dying with them, our language dying with them, our stories dying with them. It's not to demean other people are dying who are non-Native. It's just saying the quality of the people that are dying from this in Native communities is heartbreaking. It's heartbreaking, too, because you know, language is what makes us Indigenous communities, right?”

Bennett-Begaye says that the wisdom lost with the death of elders is a torch she wants to carry forward in her work. She observes that so much writing about Indigenous peoples in mainstream media conveys a message of “poor, poor Native people. They can’t help themselves. But I'm, like: ‘Uh, we survived 500 years. We're doing pretty awesome.’ There's so much [of] what we call 'Indigenous excellence' [and] 'Indigenous brilliance' that they [non-Native people] don't know.”

The deep care that many Native communities took with the elderly is another vivid memory. She mentions that the Navajo nation not only had contactless food drops for older residents, but that some communities “would also have a red or green card to stick in the window to make sure [they] were okay. If they needed anything, they put red on their window.”

Bennett-Begaye’s database also continued to rise to meet challenges. What started as a personal Excel sheet has become a full-fledged project taken on by Johns Hopkins University, where a research team now seeks to regularize the data collection she had once accomplished through phone calls and follow-ups.

“Right now, they have 76 tribes,” she says. “What we're trying to do is get permission and just build a relationship with tribes. Now [after the election season within Native communities] they're able to establish those relationships, and hopefully get more tribes involved or at least get a place where they can get their links and what not.”

These links would connect to real-time reported data from the tribes to the database, rather than relying on Facebook posts and other social media platforms. And the rollout of vaccinations has added a new, and very positive, statistic to the database.

Our Community Needs Us (March 19, 2021)

Various bureaucratic barriers had kept Bennett-Begaye from receiving her own vaccination. But she finally traveled back home to New Mexico to get her dose.

“I got in my cheii’s car and I started crying,” she says. “Because I knew I was going to the vaccination site, and I was like: “I’ve got to do this. I'm doing this for him.”

Bennett-Begaye’s database has tracked the impact that COVID-19 has had on Native communities. But why they have been hit so hard is a difficult question to answer. The federal government’s history of forcing Native people into locations where their health and well-being can be compromised is one factor – and this environmental subjugation has heightened health disparities.

Yet Bennett-Begaye also observes that social distancing is also an issue, especially because Native populations with multi-generational households – and elders whose lives revolve around social interaction – find it challenging to practice.

“Native people are so community oriented,” she observes. “We love to meet up and visit and talk and socialize. I mean, we really take seriously that kinship we have with one another. I think when the virus spread like through Navajo… even for my parents it was really hard for a lot of people to process that we can't go up and hug the elder or shake their hands or, you know, see how they're doing. I mean, it was hard for my cheii to not go anywhere.”

Yet Indian Country Today’s Managing Editor observes that community has also had positive benefits in dealing with the pandemic. “They did a study with around 3000 Native people to see if they would take the vaccine and 75 percent of them said they would,” she says. “And the motivation, the driver behind that, was [that it was] for their community.”

Bennett-Begaye feared losing her capacity as a reporter as she was promoted quickly into editing positions. But the pandemic year has been a year of growth for her, and for Indian Country Today as well. Indeed, the first interview that Secretary Haaland gave was to Native media.

“We started a broadcast during the pandemic,” she observes. “Who does that? I just think that [the] pandemic was kind of was like a huge epiphany for [our publication]. Our community needs us. We need to cover this. People all the time are wondering: Who would we turn to? Who do we read? And I think we took that responsibility upon ourselves to be that source of information. We do see ourselves as a public service.”

Alex Long is a Program Associate for the Science and Technology Innovation Program (STIP) at the Wilson Center, focusing on STIP’s Innovation Initiatives. Alex also is a Junior Policy Fellow with Cambridge University’s Centre for Science and Policy to research global health policy innovation.

Cover Photograph: The American flag flies at half staff above the White House on February 22, 2021 to honor the 500,000 Americans who lost their lives in the COVID-19 pandemic. (Official White House Photo by Chandler West)