Summer 2021

A River Runs Through It

– Christopher Sands

The United States and Canada struggle to manage cross-border challenges. Is a new model needed?

The Columbia River defines the Pacific Northwest for both Canada and the United States. It runs for 1,243 miles from the Canadian Rockies to reach the Pacific Ocean. It also forms part of the border between Washington and Oregon.

In 1858, the British extended the claim of their colony on Vancouver Island inland, renaming it “British Columbia”. Had history unfolded differently, the two U.S. states carved out of the Oregon Country might have become “American Columbia” in response.

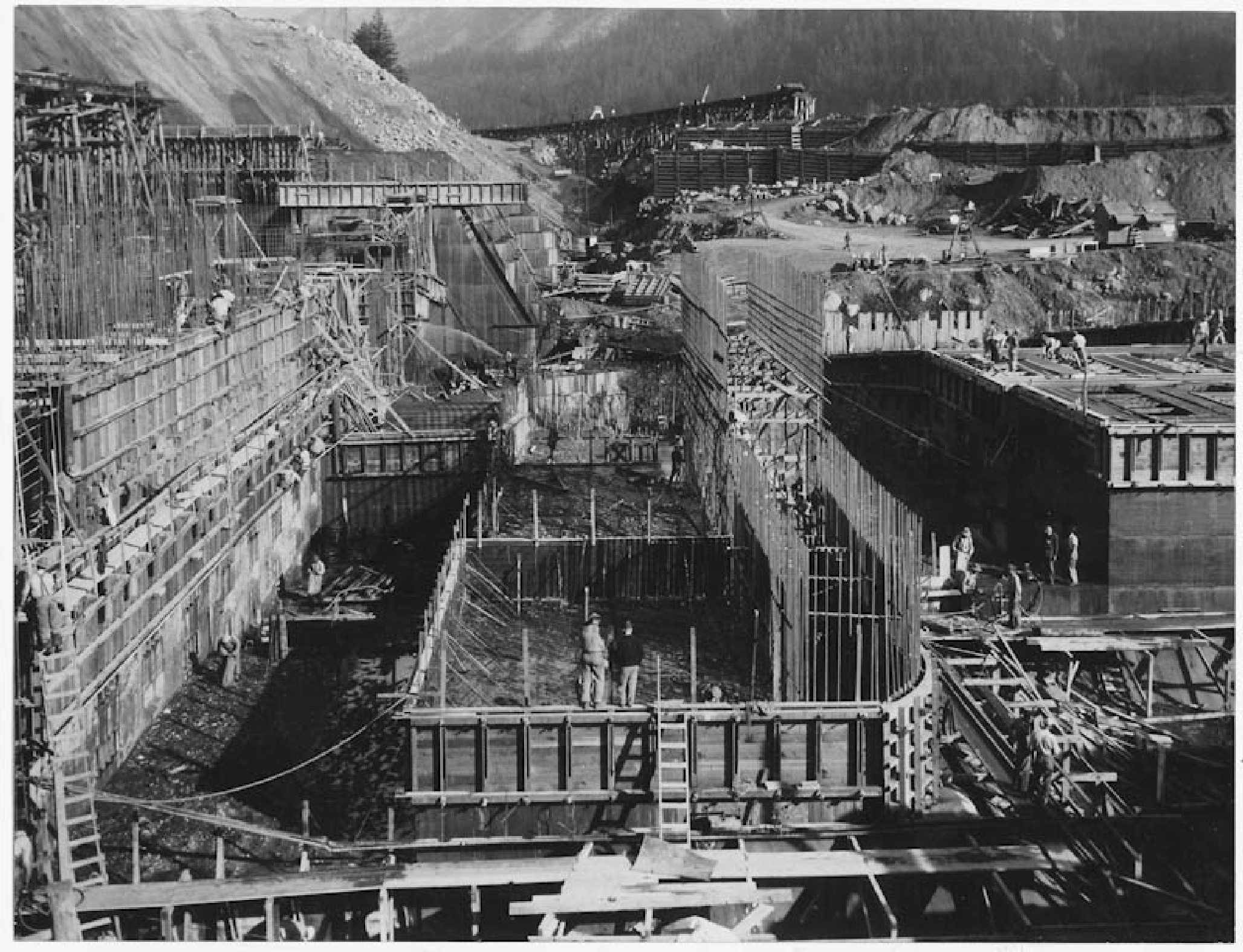

Eighty years later, the Columbia River was in the spotlight again when U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt fulfilled a campaign promise in 1937 and dedicated the Bonneville Dam – the first hydroelectric dam on the Columbia. The electricity generated at Bonneville made it possible to smelt local bauxite to make aluminum. And it was that metal which allowed Boeing to produce aircraft that helped the United States and its allies – including Canada – to prevail in World War II. The industry also drew thousands to the Pacific Northwest in that era – a wave of western migration not seen since the region’s abundant forests drew lumberjacks to the area.

Today there are more than sixty dams on the Columbia River and its tributaries. Fourteen of those dams are on the Columbia itself, with an additional three in Canada and the rest down river in the United States. Since a dam upstream in Canada can affect the water flow to downstream dams in the United States, the two countries negotiated their first Columbia River Treaty in 1961.

The treaty reflects an agreement on the water flow and a sharing of the hydroelectric power potential of the river that benefits all parties. The major metropolises of Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver all depend on the Columbia for electricity that is generated without carbon emissions. This clean energy is an attractive feature for today’s environmentally conscious residents of the Pacific Northwest on both sides of the border.

In 2018, diplomats from Canada and the United States began negotiating an update to the Columbia River Treaty. Local residents wanted more power from potentially fewer and more efficient dams that would interfere less with river fish and wildlife, and the two federal governments are still working to strike a deal that satisfies these goals in a mutually acceptable new agreement. Canada and the United States are partners in managing the Columbia, but their industries and local residents are also competitors. To some extent, each sides’ gains come at the expense of the other party.

The history of treaties and other agreements between these two North American neighbors often illustrates the delicate interplay between cooperation and competition. What can we learn from that history? And why might the Columbia River Treaty be a leading indicator for the relationship?

Borders and their Consequences

Few problems vex international relations more than the management of finite resources that cross borders. Yet one can’t begin to grapple with that problem until the borders are determined.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the United States and Great Britain (on behalf of the British Empire’s North American colonies) gradually fought and negotiated to settle the border between America and the Dominion of Canada (after 1867).

One cause of the War of 1812 was Britain’s occupation of forts in the Old Northwest that were ceded to the new United States under the terms of the 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the American Revolution. Subsequent armed conflicts over the border were, thankfully, smaller in scale.

The Aroostook War (1838-1839) was fought over the boundary between Maine and New Brunswick. The Treaty of Oregon (1846) was supposed to have settled the border in the Pacific Northwest at the 49th parallel, ending President Polk’s threat to set the border unilaterally at 54-40 north latitude “or fight!” However, in 1859, an American settler on San Juan Island shot a pig owned by a British settler and the Pig War began. The pig was the only casualty in what became a standoff as the U.S. Civil War erupted.

The border was only settled in 1871, when the United States and Britain signed the Treaty of Washington that committed both sides to submit border claims to an international arbitration panel chaired by Kaiser Wilhelm I of the German Empire. The arbitration gave the United States control of San Juan Island in 1872.

A few maritime border disputes between the United States and Canada exist even to this day, but the last major border dispute with Britain was the Alaska Boundary dispute. The British and Russian empires argued over the border between Alaska and British North America starting in 1821. When the United States purchased Alaska in 1867, it also took on the dispute, which gained new intensity after gold was found in the Yukon and drew prospectors north. During the Yukon Gold Rush of 1898-1899, the only way in and out of the Yukon by ship was through the port of Skagway; Whichever country controlled Skagway stood to benefit handsomely.

.jpg)

The United States and Britain agreed to settle the dispute with a ten-person arbitration panel. Five American arbitrators joined four from Canada and a retired British judge chaired the British-Canadian side. U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt was delighted when the British judge sided with the Americans to settle the dispute in 1903, but Canadians were outraged. Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier felt the British had resolved a dispute with their global rivals, the Americans, at the expense of Canadian interests.

There Had to Be a Better Way

As part of the British Empire, the Dominion of Canada did not have the right to set its own foreign policy independently. The Canadian reaction to the Alaska Boundary settlement provided an opening for Washington to draw Canada away from the British Empire, simultaneously weakening a global rival and striking a blow against colonialism, which the United States objected to on principle.

The administration of U.S. President William Howard Taft made the promotion of Canadian sovereignty (distinct from British sovereignty over Canada) the central plank in American foreign policy toward its North American neighbor. It signed the Boundary Waters Treaty of 1909 with the Dominion of Canada and established the International Joint Commission (IJC) to foster cooperation on the Great Lakes and rivers – like the Columbia – that crossed the border. Britain acquiesced to the establishment of the IJC without any British representation because it saw it as a purely local matter, but an important precedent had been set.

Canadians embraced the new approach. They believed that the brash Americans could be bullies, and the only way to deal with a bully was to stand up for yourself. The United States was independent, Canada was a colony; the United States had a bigger economy, but Canada was a source of natural resources that the Americans needed; the United States had a bigger military, but Canada and Britain had successfully convinced the Americans to resolve border disputes according to the rule of law and peaceful arbitration.

.jpg)

By establishing a bilateral relationship on the principle of equal national sovereignty, the United States and Canada could deal with one another as sovereign equals. For Canada, it was no longer necessary to have British protection to escape American invasion or domination. Canadians had achieved something more powerful by winning American respect for its rights as a neighbor and partner.

As the 20th century progressed and the British Empire ended, the U.S-Canada relationship was a model for a new sort of international relations that would endure even as the two countries grew more integrated economically and societally because they remained politically and legally sovereign equals.

Nature Without Borders

Joint management of cross border issues on the principle of sovereign equality in the 20th century built on the settlement of border lines in the 19th century. The Columbia River Treaty negotiations currently underway show that the model can still work well. Yet after a century of good relations guided by respect for national sovereignty, there are signs that the bilateral relationship may be entering a new and troublesome phase.

In 1984, Johns Hopkins University Professor Charles F. Doran warned that unless the United States and Canada maintained their commitment to working together as equals and as partners in addressing shared challenges, the famed U.S.–Canada relationship could fall into acrimony and distrust. Doran’s book, Forgotten Partnership: U.S.-Canada Relations Today, was in part a response to growing tensions over Canadian economic nationalism promoted by Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and geopolitical differences over U.S. conduct in the Cold War, from the war in Vietnam to the Cuban Embargo.

Becoming a global superpower took U.S. attention beyond its own regional neighborhood. In the view of many Canadians, it also led relations in that neighborhood astray. If the United States had forgotten the principles of the partnership with Canada, as Doran wrote, then Canada would need to find its own way in the world., Therefore, economic nationalism and engaging with nonaligned nations in the Global South were options worth exploring.

However, shortly after the publication of Doran’s book, Canadians elected a new government headed by Prime Minister Brian Mulroney. Mulroney was pro-American and a natural salesman, and soon got to work reminding the Americans that Canada was still a partner, and that the partnership could still yield benefits for both countries.

Mulroney worked with U.S. President Ronald Reagan to negotiate the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement in 1988, and with President George H. W. Bush to negotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement ratified in 1993. NAFTA added new mechanisms for managing cross border issues, from environmental challenges to integrating cross-border supply chains, and these gave each country equal representation. We remembered the “forgotten partnership” just in time.

America First, Canada Last – or Lost

Today, the 1990s looks like a golden age of bilateral partnership between the two nations. Since then, both countries have put national needs first. Not always, or in every case, but in ways that eroded confidence in the partnership.

After the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States, President George W. Bush proposed that Canada join the United States in securing the perimeter through common screening at airports, seaports, and data sharing; Prime Minister Jean Chrétien rejected the offer. So the United States took steps to dramatically reinforce border security itself. Canada eventually did the same.

Prime Minister Stephen Harper volunteered Canada to help fund bailouts for General Motors and Chrysler following the 2008-2009 financial crisis, but Congress attached “Buy American” requirements to stimulus legislation that violated NAFTA commitments. President Barack Obama also rarely acknowledged Canadian support for the Detroit automakers.

Yet it has been conflicts over energy and the environment that have done the most damage to the partnership, embittering citizens on both sides of the border and making it more difficult for leaders in Ottawa and Washington to cooperate.

Canada is fortunate to have vast energy resources, but there is a catch: many of these resources are in remote locations and costly to develop. With a population of 37 million people stretched across a territory 10 percent larger than the United States and spanning seven time zones, domestic energy needs alone would not sustain the development of Canada’s energy resources. Canada is lucky again because it has the U.S. market right next door.

At the turn of the 21st century, energy overtook motor vehicles as the largest category of Canada’s exports to the United States. A network of pipelines and power lines connect hydroelectric dams on northern Canadian rivers to the U.S. electric grid, and oil, gas, propane and more to refineries across the United States. Interconnections link energy networks in both countries and provide resilience and competitive prices for consumers.

That led an Alberta company then called TransCanada to propose in 2008 an extension of its Keystone pipeline network to bring Canadian oil to refineries on the U.S. Gulf Coast. Because the pipeline crosses the U.S. border, it requires a presidential permit from the United States. This was a requirement established by executive orders, rather than by statute – that is, the executive branch established the requirement, not Congress.

The battle was fierce and swung back and forth. Environmental groups demanded that President Obama deny a presidential permit to the Keystone XL project and he ultimately did so. President Donald Trump granted a presidential permit based on a new application in 2017; President Biden revoked the permit by executive order on his first day as president. At every turn in the Keystone XL saga, the White House made its decision based on domestic political debates, and whether one favors one decision over the other, it is clear that the fate of Keystone XL was determined by putting American interests first. Canadians do not get a vote in U.S. elections, or representation in Congress.

Further east another series of decisions reinforced the message. In 1991, Hydro Quebec proposed to build power transmission lines to bring electricity generated by dams on rivers flowing into James Bay to electric utility companies in New England states. Canadian hydroelectricity was attractive to some governments and consumers because it produces no carbon emissions and is renewable. Environmental groups opposed these projects claiming that large scale dams damages ecosystems. They also argued that imported Canadian electricity would let New England utilities avoid investing in local renewable projects. Following a series of court battles and statewide referendums, most of the seven different projects proposed have been cancelled or put on hold.

A Michigan Melee

Two of the biggest cross border fights have broken out in Michigan. One of these, over a pipeline, has generated the biggest bilateral crisis of President Joseph Biden’s administration to date.

Shortly after the September 11 attacks, business groups and national security experts in both countries saw the need for a new bridge across the Detroit River. A new bridge would add traffic capacity and address the vulnerability of the current Ambassador Bridge.

Built in 1927, the Ambassador Bridge each year conveys more trade by value than the United States has with all of Europe in the same period. The owner of the Ambassador Bridge lobbied local politicians against the new bridge and financed two state ballot initiatives designed to block the project. As a result, Michigan legislators would not approve funding for 25 percent of the cost of the new bridge (Ontario and the two federal governments were committed to fund 25 percent of the project cost each).

Canada agreed to cover the Michigan’s share of the cost to make sure the new bridge project went ahead. Later, when Congress neglected to fund construction of a U.S. Customs plaza on the American side of the new bridge, Canada came up with funds to finance this, too. At least the Canadians gained the rights to name the new bridge after Canadian hockey star Gordie Howe, who played for most of his career for the Detroit Red Wings.

Michigan’s state government prompted another crisis over a pipeline built in 1956. The owner, the Canadian company Enbridge, wants to spend $500 million to upgrade it by adding both greater capacity and new technology to prevent and detect leaks of the oil, natural gas, and propane carried through the pipeline prosaically known as Line 5.

Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer has revoked the operating permit for the pipeline as well as approval for the upgrade, citing the risk of a leak from the pipeline as it runs underwater through the Strait of Mackinac between the Upper and Lower peninsulas of Michigan. Enbridge has sought federal mediation, arguing that an international pipeline falls under federal jurisdiction in the United States.

For Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, the fight over Line 5 is more worrying than the abrupt decision by President Biden to cancel the Keystone XL pipeline’s presidential permit. This is because Line 5 supplies not only Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania – it is the principal supply for Ontario and Quebec as well. Shutting down Line 5 denies Canadians access to their own oil and gas.

Sharing the Neighborhood

Despite these battles, Canada has continued to act as a partner, rather than a rival. The best example of this is the joint border restrictions adopted in March 2020 to slow the spread of COVID-19. Renewed every 30 days since, Canada and the United States are permitting only essential – mainly commercial – transit across the border. The policy has been a partnership, but it has already been the longest sustained closure of the border in history.

Away from the border, the two countries have adopted pandemic responses, from business closures to quarantine requirements, without any coordination. The United States has expanded vaccine production, and Canada has sought to obtain enough vaccine doses on international markets (including from producers in the United States). An unknown number of Canadians traveled to the United States to get a COVID vaccine when none were available in Canada. Even now, as the United States has more vaccine supply than demand, on vaccinations, Canada and the United States are merely neighbors and not partners.

It is in the currents of this history that the talks on a new Columbia River Treaty are proceeding. They are not without controversy, but they do remain firmly grounded in the partnership model that appears headed toward a reasonable compromise.

So why might this border issue be different from all the others we have examined?

The original Columbia River Treaty in 1961 was a partnership of equals to manage a shared, finite resource. Today, when the United States puts American domestic policy fights first, we end up litigating the terms of the U.S.-Canada relationship rather than negotiating them. This approach means that the U.S. loses a lot of goodwill.

At their first virtual bilateral meeting in February, President Biden and Prime Minister Trudeau agreed on a new agenda for the relationship. They called it a “Roadmap for a Renewed U.S.-Canada Partnership” with 44 action items in the document. The reference to partnership is encouraging, but for the “Roadmap” to get us back to the partnership model, Americans have to remember why we adopted a partnership approach to Canada a century ago. Partnership is the best way to advance U.S. national interests with our Canadian neighbors. By showing mutual respect and consideration for one another – and not drawing the neighbors into our domestic disputes.

If we have forgotten that, it is more than our relationship with Canada that is in trouble.

Christopher Sands is the Director of The Wilson Center's Canada Institute.

Cover photograph: The Grand Coulee Dam on the Columbia River. ( Nadia Yong / Shutterstock.com)