As Mexicans buck political status quo, Independent “El Bronco” wins election

– Duncan Wood

In Mexico, an independent's election as governor marks a potential sea change in Mexican politics, as voters grow increasingly disillusioned with traditional political elites.

A Break with Tradition

As the votes from Sunday’s midterm elections were counted in Mexico, it was clear to everyone what the story of the campaigns would be. Jaime Rodríguez Calderón, better known as El Bronco (the rough one), is projected to be the clear winner in the Nuevo León gubernatorial election, more than doubling the vote received by each of his nearest rivals from the ruling Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) and opposition Partido Acción Nacional (PAN) parties.

The truly remarkable thing about Calderón’s candidacy is not his margin of victory, but that he ran and won as an independent — this was the first time in Mexican history that such candidacies were possible. His victory marks a potential sea change in Mexican politics, with voters increasingly tired of the established parties and disillusioned with the traditional political elites.

The midterms were expected to change little at the national level, and at first glance that is what appears to have happened: the ruling PRI held on to its dominance of the federal congress, and there was only sporadic electoral violence in the states of Oaxaca and Guerrero. Yet, a number of key stories emerged on Election Day that hint at significant trends in Mexican democracy.

First, the PRI only managed to hold onto its leading position by working closely with two other parties, the Verde (Green) and PANAL (a teachers’ union party). The PRI’s vote fell to around 29 percent, down from almost 32 percent support in the 2012 congressional elections. With the support of its allies, and the even more disappointing performance of the opposition PAN (21 percent) and PRD (10.6 percent), it will be able to maintain its majority in congress.

Second, there was a high turnout, indicating that the Mexican public was indeed motivated to participate and that the parties were anxious to get as many supporters as possible to the polls.

Third, the left is more divided than ever — the well-established PRD was almost matched in the polls by the breakaway Morena party, run by former PRD leader Andrés Manuel López Obrador. When the votes for the leftwing parties (PRD, Morena, Movimiento Ciudadana, PT) are added together, their total comes to almost the exact same number as the PRI’s.

Fourth, there appears to have been a very high number of spoiled ballots (voto nulo) — almost five percent of the total number of votes cast. This points to a worrying trend towards electoral disenchantment, a tendency borne out by polling data on Mexican skepticism about democracy in recent years.

But the story of the election is clearly El Bronco. The independent candidate for the governorship of Nuevo León, a wealthy northern border state and one of the country’s industrial engines. In his victory, Rodríguez broke the mold of Mexican elections by proving that success can come from outside of the established party system. As an independent, Rodríguez was one of fifty candidates nationwide running without party affiliation — in this, the first election in Mexican history where independents were allowed to run for office.

The national and international media attention El Bronco attracted virtually guaranteed that even if he did not win the governorship, many more independent candidates would come forward in forthcoming elections, including the 2018 presidential contest. Mexicans’ growing disillusionment with traditional party politics and the established modes of democracy in their country may just see an outlet in the prospect of candidates who have broken free from the dominant party paradigm.

Lone Ranger or Professional Politician?

“I’m not saying I am Superman, but I could be the Lone Ranger.” El Bronco used this phrase repeatedly during the race, and it served him well. Voters clearly identified with his outsider status, and he appears to have won 49 percent of the vote in Nuevo León, compared with 23 percent each for the PRI and PAN candidates.

Of the 50 independents running in this election, only one other candidate won election, and this is no accident. Current electoral rules make it difficult for independents to compete with candidates from Mexico’s well-established political parties. Though independent candidates are allowed to have access to promotion on radio and television, candidates from political parties receive much more airtime. Campaign funding — which in Mexico has traditionally been entirely public — is more uneven still: independents receive less than one percent the amount the public funding received by their competitors from established political parties.

Though independent candidates can receive private funding, the rules governing this have not been clearly delimited by the authorities. Nor is there clarity on the rules governing independents’ campaign spending. In El Bronco’s race, local authorities declared that the amount of private funds that a candidate can use cannot exceed 10 percent of total campaign expenses. In theory, these rules apply to candidates who receive public money through political parties. If they were applied to El Bronco, it would jeopardize his position because he received the equivalent of $23,000 in public financing — compared to the nearly $3 million that his competitors received just through their political parties. This legal uncertainty raises the prospect of postelectoral instability, challenges, and conflict.

Despite these challenges, El Bronco led the polls in Nuevo León for the past three months, jumping nearly 16 points since March. He received a further boost when, a few weeks ago, Fernando Elizondo, a former interim governor and senator, dropped out of the race and threw his support behind Rodríguez.

Rodríguez’s performance is partly a testament to his considerable political savvy and experience, and partly a reflection of his roots in local and sectoral politics. He is originally from Pablillo, a small town in central Nuevo León with fewer than one thousand inhabitants. As a young agricultural engineering student, Rodríguez fought against increases in public transportation fares and later became the leader of the National Agricultural Confederation in Nuevo León. For that post, he responded to an opponent’s complaints that he wore “exotic leather boots and jeans purchased in the United States” with a speech that rallied farmers to “stop thinking squat, and instead think big,” inviting them to dream of better boots, better tractors, and better incomes. These battles honed his campaign skills and furthered his image as a charismatic, nontraditional politico.

In 2009, after climbing the political ladder to become a federal and local deputy, Rodríguez won election as mayor of García, a municipality with a population of around 145,000 that is part of the metropolitan area of Monterrey, Nuevo León’s capital. Here, he earned a reputation as a strong and determined character.

His government philosophy is called the “García model,” and focuses on three policy areas: security, education, and labor. He considers the participation of government, citizens, and businesses to be fundamental to good governance. To facilitate this as mayor, he used unconventional methods — publishing his private telephone number so he could receive requests directly from the citizenry, or registering complaints and requests through his Facebook page.

At that time, he realized that security was the number one concern of the electorate, so as a first step, he launched a strategy to take back some public spaces that had been claimed by criminals. More dramatically, he dismissed all of the municipal police in García. Those actions won him public trust, but also made him a target of organized crime groups, who kidnapped his two-year-old daughter, murdered one of his older sons, killed his city’s public security minister in the municipality, and tried twice to assassinate him.

As insecurity and violence decreased in Nuevo León, his popularity transcended his term in office and the figure of El Bronco became known in the state and nationwide, with songs and even a film, Un Bronco Sin Miedo (A fearless Bronco), inspired by his story.

In September 2014, Rodríguez decided to give up his membership to the PRI because he foresaw difficulties in obtaining the nomination to run for governor. In his resignation letter, he expressed the ideas that became the banners of his campaign for governor: political parties are no longer responsive to citizens’ demands, and the community is angry and tired of corrupt politicians.

Relying heavily on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube as means to promote himself, he obtained registration as gubernatorial candidate. El Bronco ran his campaign based on the strength of his personality and charisma. Through informal and often obscenity-laced speeches, he increased his popular support, promising to always speak the truth to citizens, and insisting that with courage and strategy, an effective and lasting security strategy can be built.

The meaning of El Bronco

Doubts remain as to the nature of the governor-elect. Is he truly independent, breaking away from the established model, or should we instead see him as a former party man who is first and foremost an opportunist and professional politician, someone who has seen the writing on the wall and is willing to do what it takes to win office?

No matter what kind of governor El Bronco turns out to be, the rise of independent candidates should be read as a call for political parties to increase internal competition and improve the quality of their candidates. Parties clearly need to recapture the allegiance of the growing number of Mexicans who have lost faith in the established model. At the same time, civil society movements such as the 3de3 initiative (which calls on candidates to make a full disclosure of their business and financial interests) are raising public awareness about the issues of corruption and conflict of interest. Latinobarómetro polls consistently place Mexico at or near the bottom of the Latin American region in terms of citizen satisfaction with democracy.

Whatever the more generalized implications of this for elections, El Bronco’s particular style of governing will be difficult to repeat at the gubernatorial level, and he will have to find new ways to face the challenges to come. Nonetheless, Jaime Rodríguez Calderón has bucked the status quo and emerged as the most compelling character of Mexico’s 2015 midterms.

More intriguingly, as Luis Carlos Ugalde, former president of the electoral body in Mexico, recently said in an event at the Wilson Center, we cannot rule out the possibility that an independent candidate could run for president in 2018; while he or she will not likely have the strength to emerge victorious, they might win enough votes to tip the balance.

The rise of El Bronco is emblematic of the rising disenchantment on the part of the Mexican electorate with the country’s political parties, and will likely prove to be a disruptive factor in national politics for years to come.

* * *

Duncan Wood is the director of the Mexico Institute at the Wilson Center. Follow him on Twitter at @AztecDuncan. Pedro Valenzuela is a consultant with the Mexico Institute. Photo courtesy of Reuters/Stringer Shanghai

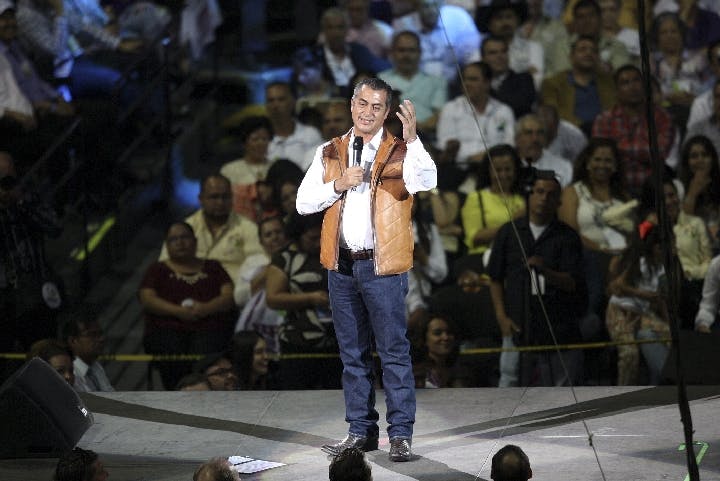

Cover image: El Bronco addresses an arena filled with supporters in May 2015. Photo courtesy of Reuters/Stringer Shanghai