Is cultural repatriation just knee-jerk cultural nationalism?

– Eric Nong

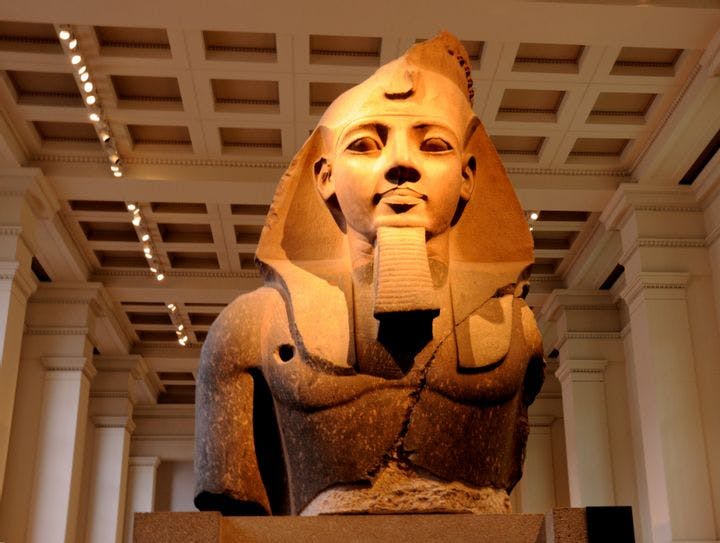

Should an Egyptian artifact be in a British museum? That question merits a broader conversation: does our cultural heritage belong to a people, a place, or the world?

Visit the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the British Museum in London, the Louvre in Paris — any of the world’s great art museums — and you expect to see artifacts from a diverse array of cultures, historic eras, and corners of the planet. These museums (among many others) have long staked their reputations on their collections’ historic value and the importance of these objects in the cultural life of ancient civilizations in distant lands.

What do we feel when we look upon these works — and should that reaction change when we pause to consider how these artifacts were attained? In his essay in the November/December 2014 edition of Foreign Affairs, James Cuno, President and CEO of the J. Paul Getty Trust (which owns and operates the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles), criticizes what he believes has been an excessive wave of cultural protectionism in recent decades.

Through an institutional lens, international regulation of cultural property began after a 1970 UNESCO convention (which has 115 signatories, including the United States) intended to prevent the illegal trading of archaeological findings. Though the convention is not international law, was largely ignored in its early years, and is unable to nullify a nation’s pre-1970 laws regarding cultural artifacts, its signatories now largely behave in accordance with its foundational conditions. The Association of Art Museum Directors and the International Council of Museums, two of the largest museum-affiliated NGOs in the world, have adopted policies to align themselves with UNESCO.

This, charges Cuno, has created an atmosphere overly permissive to highly publicized repatriation claims over cultural artifacts. Nations that were once home to prosperous ancient cultures — Egypt, Greece, Iran, Iraq, Italy, Turkey — have been most active in filing repatriation requests, framing themselves as the rightful heirs of their ancestral cultures’ belongings. Whether pilfered through black markets or imperial governments, these historic objects are central to national pride and identity, which (at least to the plaintiff countries) makes these renowned museums accessories to a massive cultural crime, rather than their fancied traditional role as protectors of world culture.

Cuno — whose Getty Museum has been a regular target for repatriation claims in the last decade — counters that repatriation claims are often simple knee-jerk nationalistic reactions and ultimately counterproductive to the preservation of a nation’s cultural heritage. “Promotion of cultural purity, borne of uncertainty,” writes Cuno, “can produce dangerous, often violent, xenophobia.” Meanwhile, Cuno extols the Western “encyclopedic museums” of art and history, which display a diverse variety of art and artifacts — and in so doing, “promote a cosmopolitan worldview, as opposed to a nationalist concept of cultural identity.” Cultural diffusion, a hallmark of globalization, curiosity, and international tolerance, is central to the very concept of an encyclopedic museum.

To reverse the effects of cultural imperialism and reduce what he perceives to be an excessive amount of repatriation claims, he urges non-encyclopedic museums to be more open to loaning artworks and artifacts while advocating for the construction of encyclopedic museums “everywhere in the world where they do not now exist.”

While enticing in concept, nations lacking an encyclopedic museum tend also to lack the economic means to support such a cultural gem. The most prosperous pockets of Western world have had substantial experience with museums to the point where encyclopedic museums and even local, non-encyclopedic museums are considered a fixture of a city’s identity (the Louvre is unmistakably Parisian, and Washington, D.C., is unimaginable without its constellation of Smithsonians). In less advantaged countries, there is less lived experience with the concept of a museum occupying a key place in a people’s social fabric (let alone an encyclopedic museum). Coupled with imbalances regarding the possession cultural works — a problem exacerbated by existing encyclopedic museums and their hostility towards repatriation — these countries may not have experience in building, curating, maintaining, and managing an encyclopedic museum from scratch. These newer museums would almost certainly have to work with the West's existing encyclopedic museums, which could impede a newer museum’s efforts to forge its own local and national identity — which, one could argue, is just a friendlier form of imperialism.

At present, there are no binding international laws to set standards and norms for art repatriation, nor are there arbitrating bodies where plaintiffs and owners can contest claims. Precedents of one form or another are being set, but as it stands, there are no clear answers whether these museum pieces belong to the world or to a people — and how the lived reality of that answer should look.

* * *

The Source: “Culture War” by James Cuno, Foreign Affairs, November/December 2014.

Photo courtesy of Flickr/Rejik