Do we have an obligation to find a less cruel way to kill inmates?

– Marlene Uribe

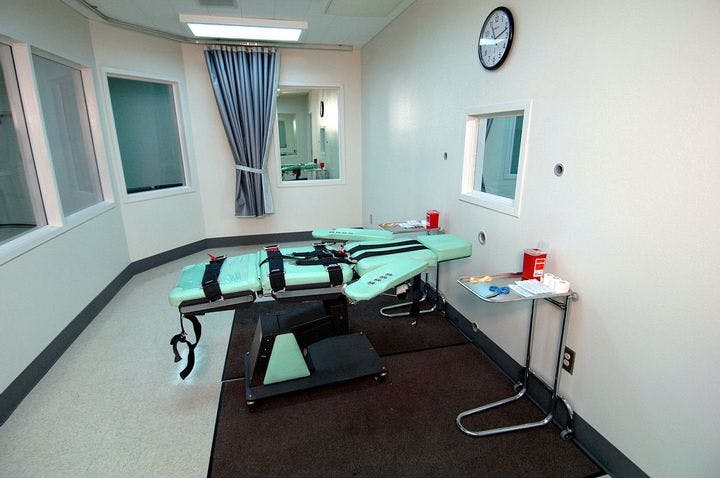

Lethal injection may be "less barbaric" than some alternatives, but it's still barbaric. Is there a better alternative?

Is there a least-bad way to be killed?

In his 1994 opinion in Callins v. Collins, Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia limns out two violent, barbarous murders. Compared to such grisly ends, “how enviable a quiet death by lethal injection,” Scalia writes.

“Such executions are billed as quiet and painless,” writes Ben Crair in The New Republic, but recent evidence points towards the cruelty of lethal injection. The botched execution of Angel Diaz offers one such example.

Convicted of murder, Angel Diaz was killed via lethal injection on December 13, 2006, by the State of Florida. His body arrived at the medical examiner's office that same evening, with I.V. catheters still attached to both arms. An autopsy revealed that one member of the execution team pushed the catheters all the way through the veins in Diaz’s forearms and into soft tissue — an error known in the medical world as “infiltration.”

According to Mark Heath, an anesthesiologist at Columbia University, when sodium thiopental (the first of three drugs in the deadly cocktail) infiltrates, it does not produce its intended effect of anesthesia. The other two drugs introduced in the process are pancuronium bromide and potassium chloride, which paralyze voluntary muscles and stop the heart, respectively. Crair explains that thiopental is the most important drug from a prisoner’s perspective; its failure allows him to feel the torture of the next two.

Due to infiltration, it is likely that Diaz was awake to feel the lethal drugs accumulate and pool in his subcutaneous tissue, producing large chemical burns. The skin on Diaz’s arms burned, greyed, and sloughed off, exposing fresh blisters filled with what the autopsy called a “watery pink-tinged fluid.” The execution, which should have only taken 15 minutes, took a full 34 minutes. “It seemed like Angel Nieves Diaz would never die,” wrote Associated Press reporter Ron Word, who witnessed the execution.

What explains the infiltration? According to Crair, prisoners sentenced to death are often overweight and former drug users — and this could make it difficult to find a vein — but not so in Diaz’s case. Two days after Diaz’s death, then-Governor Jeb Bush suspended executions in Florida and assembled a panel of doctors and politicians to revise the state’s lethal injection methods. “The panel found that Diaz’s execution team lacked appropriate training and failed to follow the proper steps,” writes Crair.

The Florida Commission still finds it impossible to declare whether Diaz was ever in pain. Indeed, the most the group did was recommend alternative chemicals, better training for the execution team, and a close monitoring of inmates’ health conditions.

Diaz’s death seems to have changed little in the administration of lethal injections nationwide. Earlier this year, the public learned (in near-real-time, thanks to tweets from a reporter on the scene) of a similarly botched execution. On April 29, convicted murderer and rapist Clayton Lockett was put to death by the state of Oklahoma. It reportedly took the execution team 51 minutes to find a vein for the midazolam I.V. They eventually settled on one deep in Lockett’s groin.

The Oklahoma Department of Corrections says that the vein collapsed, causing the execution drugs to saturate his soft tissue. “Witnesses say [Lockett] writhed, clenched his teeth, and mumbled throughout the procedure,” writes Crair. The inmate was pronounced dead an hour and 47 minutes after having initiated a process that should have taken ten.

Bill Wiseman, the Oklahoma state representative who led the fight to introduce lethal injection to the state in 1977, once described the administration of the penalty as “no pain, no spasms, no smells or sounds — just sleep then death.”

Over years, throughout the country, across countless examples, each one of those descriptors — “no pain, no spasms, no smells or sounds” — stands in marked contrast to the lived experience of lethal injection. Even if substitutes for thiopental are correctly administered, ”the prisoner could still suffer, motionlessly, if the drugs fail to knock him out.”

“A death-penalty method that was supposed to be less barbaric than its predecessors,” writes Crair, “can still mutilate the human body.”

The Source: “And The Damage Done” by Ben Crair, in The New Republic, June 30, 2014.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons