Does the World Need the Idea of “Bad” Germans?

– Peter Gumbel

Since World War Two, guilt and shame have defined Germany's international role. Why does the world still cling to the idea of "bad" Germans?

THIS IS A BIG COMMEMORATION YEAR IN EUROPE, with the 100th anniversary of the outbreak of World War I, the 75th anniversary of the start of World War II, and the 70th anniversary of D-Day. So it was to be expected that German president Joachim Gauck should give a speech early in the year to set the tone.

Gauck, 74, is a Lutheran pastor who grew up in the former East Germany and is widely viewed in his home country as a moral authority. After German reunification in the 1990s, he ran the agency that was in charge of reviewing the Stasi secret police files on millions of East German citizens. It was a delicate task that required balancing reconciliation with justice, and he handled it with aplomb.

In his speech at a security conference in Munich this January, Gauck didn’t miss the opportunity to talk about German history, but he didn’t dwell on the usual refrain about atoning for the past. Instead, he talked about the nation’s history in the context of Germany’s role in the wider world today and in the future. For understandable reasons, he said, Germany’s past weighed heavily on its willingness to be an active participant on the world stage. But for too long it had shirked its duties and responsibilities. The time had now come for it to step up and assume a bigger role, especially in foreign and security policy.

“Are we doing what we could to stabilize our neighborhood, both in the East and in Africa?” he asked. “Are we doing what we have to in order to counter the threat of terrorism? And, in cases where we have found convincing reasons to join our allies in taking military action, are we willing to bear our fair share of the risks?” The answer going forward, Gauck made clear, should be an affirmative one. Germany needed to stop letting others protect its security, prosperity, and freedom. It needed not just to live out its values, but to “defend them credibly.”

The end of his speech was especially significant. There were reasons for the postwar generations of Germans to mistrust German statehood, he said, “but the time of categorical distrust is past.” For more than six decades, Germany had lived in peace with its neighbors, respected civil and human rights and the rule of law, and built a vibrant civil society. “There has never been an era like this in the history of our nation. This is why we are now permitted to have confidence in our abilities and should trust in ourselves.”

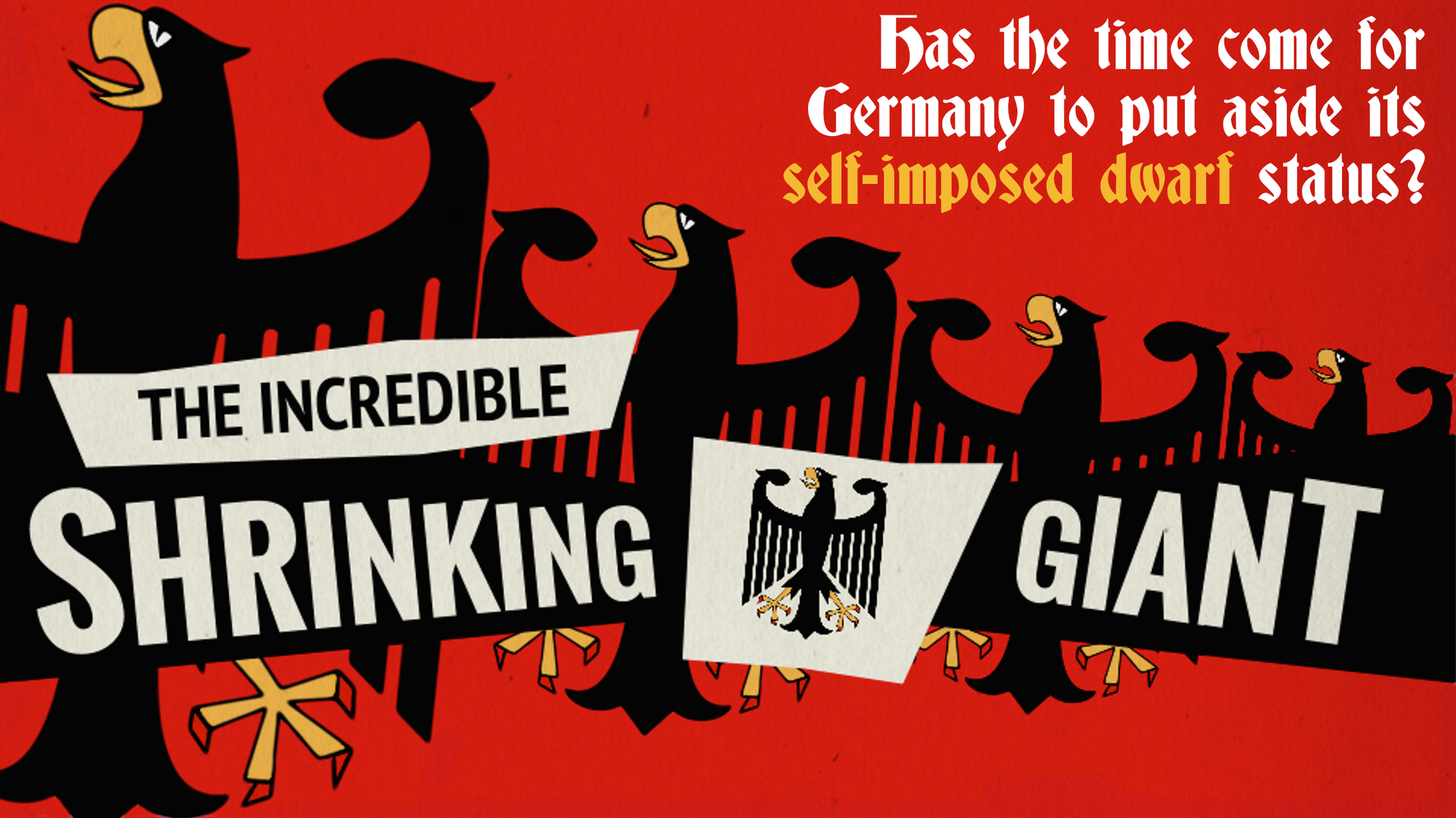

The speech received surprisingly little coverage abroad, but at home it drew widespread attention—and criticism—because it challenged a tenet of the postwar era: the idea that it was fine for Germany to have a heavyweight economy, but absolutely not fine for it to flex its political or diplomatic muscles, let alone project its military power. The Germans have a word for this condition: Selbstverzwergung, which literally means turning oneself into a dwarf. It was a condition initially imposed on a defeated Germany in 1945 by the victorious Allies: France, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States. It was also a founding notion of the European Union in the 1950s that modern Germany should be kept small, contained in a peaceful and democratic confederation of neighboring states.

The Germans have a word for this: Selbstverzwergung, which literally means ‘to turn oneself into a dwarf’

In the following decades, the concept of Selbstverzwergung was woven into the very fabric of modern German society. Germans themselves say that they don’t want their nation to be assertive on the world stage, and are particularly dubious about military intervention in other countries. Given its history of Prussian militarism, Kaiser-era belligerence, and the 12 savage years of the Third Reich, the argument goes, enough is enough. One poll conducted after Gauck’s speech showed that the German appetite for intervening in crisis areas has actually dropped sharply, to just 37 percent from 62 percent two decades ago. Four out of every five Germans said that they would like their armed forces to be engaged in international military operations even less than they already are. And overall, 60 percent of poll respondents said that restraint should be the core characteristic of German foreign policy.

This reluctance is partly a reaction to the hesitant and largely unsuccessful push for greater global engagement by Joschka Fischer, German foreign minister in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Fischer’s approach resulted in German forces participating in NATO’s bombing of Serbia and Kosovo in 1999 and joining the NATO mission in Afghanistan. But German public opinion was deeply divided about these operations, and utterly disenchanted by the subsequent US-led invasion of Iraq.

Angela Merkel, who has been chancellor since 2005, has pulled back from Fischer’s precedents. During the 2011 Libya crisis, Germany abstained on the United Nations Security Council vote authorizing the use of force, even as Britain and France joined the United States in approving it. And this year, as the Ukraine crisis boiled over, she has been on the phone to Russian President Vladimir Putin—not to rattle sabres, but as a self-appointed conciliator seeking, unsuccessfully, to persuade him to adopt a less bellicose course. Merkel did agree in early September to send some weapons to Kurds fighting Islamic State militants, a break with usual German policy, but Merkel said the decision had been “very carefully weighed” and only taken because of the "immense suffering of many people" and because Germany’s own security interests were at risk.

So it was not entirely surprising that Gauck’s call for a more assertive Germany received a lukewarm reception. In sentiments that were widely shared, conservative politician Peter Gauweiler countered that Germany’s involvement in military operations in the past few years had “simply weakened our moral and economic values and hurt our interests.”

Gauck’s speech, and the subsequent pushback, are a revealing episode, because they provide the latest evidence that even today, three score years and ten after the end of the World War II, the world—starting with the Germans themselves—still seems to need “bad” Germans.

FROM DRESDEN TO DUNKIRK TO DETROIT, the generation that lived through the war is now dead or very elderly, in their late 80s and 90s. Their children are nearing retirement age, and it’s their grandchildren and great-grandchildren who now make up the bulk of the population. Usually, this passage of time would be the point at which memory ends and history begins. Yet the Third Reich remains as significant as ever, not just as a point of reference but as a period that has defined an entire policy framework.

An old, Cold War–era joke about NATO says that it was designed to keep the Americans in, the Russians out—and the Germans down. The Cold War is over, but the existence of the Nazi past remains a dominant algorithm in the operating system of international relations. That’s especially the case for Germany itself, which shelters behind its history as an excuse to punch below its weight, or not punch at all. But it’s also true elsewhere, including in the United States.

When George W. Bush ordered the invasion of Iraq in 2003, he explicitly compared Saddam Hussein to Adolf Hitler, and invoked parallels to the 1938 Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia. The Bush-Cheney vision for postwar Iraq was strikingly similar to the 1945 template for postwar Germany—one which expected that the Iraqis would welcome American troops into their nation with open arms, thrilled that the tyrannical dictator had fallen, and be eager for the United States to preside over Iraq’s reemergence as a peaceful and democratic country. Efforts to rebuild Iraq after the war were inevitably referred to as a “Marshall Plan,” evoking the spirit of the American economic aid package that had financed the successful reconstruction of postwar Europe.

The Obama administration continues to use the same reference framework. In September 2013, as he considered options for dealing with Syrian president Bashir al-Assad’s use of chemical weapons, Secretary of State John Kerry described the situation as “our Munich moment,” a reference to the 1938 attempt by Britain and France to appease Hitler by permitting Nazi’s Germany’s partial annexation of Czechoslovakia. In March, after Russia’s move on Crimea, it was former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s turn. At a private fundraiser in California, she likened Vladimir Putin’s campaign to provide Russian passports to ethnic Russians living outside Russia’s borders to Hitler’s protection of ethnic Germans in the Sudetenland.

Such historical parallels actually do everyone a disservice. Saddam Hussein, Bashir al-Assad and Vladimir Putin are not Hitler, any more than they are Genghis Khan, Attila the Hun, or Ivan the Terrible. As Bush and Cheney found, Iraqis are not Germans, and 2014 Baghdad is nothing like 1945 Berlin. Sticking to this reference framework is a simplistic and lazy way to avoid facing the tough questions based on today’s reality.

Germany’s own idea of itself certainly seems out of sync with what’s happening on the ground. It has the largest population of the 28-nation European Union, 16 percent of the total, but accounts for more than 20 percent of the EU’s gross domestic product and 30 percent of its exports. It is the biggest single contributor to the EU budget, and for the past few crisis-ridden years it has also been about the only source of growth. But politically, too, there is no doubt over who really calls the shots in Europe these days.

You only need to look at what happened during the 2010–13 eurozone crisis. During that meltdown, the French, the Spanish, the Italians, and others wanted eurozone debts to be pooled. Merkel refused to countenance that, so it didn’t happen. She and her finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble were pivotal figures in the rescue of Greece, which ended up receiving money once it agreed to the terms that Germany wanted. The new banking union that is being put in place bears the German stamp. This year, Merkel favoured Jean-Claude Juncker as the new president of the European Commission, and overrode the very public objections of British prime minister David Cameron to give him the job. Germany has a more nuanced view of what is happening in Ukraine than countries like Poland or the Baltic states, so the EU dragged its feet on sanctions toward Russia until July, when Merkel finally lost patience with Vladimir Putin.

Of course, other factors and other players were involved in these decisions, including the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund. But Germany invariably ended up getting what it wanted. One of the most striking changes within the EU, in fact, concerns the German relationship with France. Until recently it was a truism that the two countries working together functioned as the twin motor of the EU. But the French, weakened by a frail economy and a feeble presidency, have fallen out of their driver’s seat. During much of the Euro crisis, France’s position was not aligned with Germany’s, and it ended up losing the argument. Today, in France itself, hardly a day passes without the publication of some jealous comparison between Germany’s economic strength and French weakness. President François Hollande, ill at ease with Merkel, has been casting around to align himself with new partners, especially Italy, in an attempt to soften the EU’s austerity drive. So far, these efforts have been stillborn; Germany simply won’t countenance them. Hollande’s flailing efforts have, in turn, created growing internal friction in France that prompted last week’s government reshuffle.

In other words, Germany today has the power in Europe and wields it. The answer to Henry Kissinger’s famous question about who to call when you want to speak to Europe has been answered: it’s the German Chancellery in Berlin. The central role has been particularly clear in the West’s dealings with Russia. Other European leaders have deferred to Merkel on the issue, and in August, as the Russian aid convoy approached the Ukrainian border, President Obama also reached out to her.

The timing of Gauck’s speech urging Germany to take greater responsibility for its duties was, therefore, absolutely right. He was talking about German foreign and security policy, but his plea for a change in attitude could apply to all policy. Surely, after six decades of exemplary behavior, the time has come for Germany to put aside its self-imposed dwarf status, and come out as the giant it really is?

Yet the reality is that for Germany truly to step up would require a significant cultural and political shift, not just at home but also abroad. It would require changing the algorithm, breaking out of the policy framework so shaped by what happened between 1933 and 1945. It would require the Germans themselves to want this change to happen. And it would mean overcoming some crass stereotyping elsewhere. Is that ever going to be possible?

ON JULY 8, IN THE SEMIFINALS OF THE WORLD CUP, the German team defeated the host team Brazil by 7 goals to 1, an unprecedented score. Social networks caught fire that night. Much of the commentary was sheer wonderment at the flurry of goals, as the German strikers and midfield players tore apart the Brazilian defense. But in the online commentary there was also a recurring darker theme, a stream of anti-German jibes that drew parallels between the team’s performance in Brazil and the nation’s Fascist past, often using belabored and not particularly amusing puns such as “Brazil did Nazi this coming.”

What was surprising about this anti-German meme was its virulence, and the sort of people who joined in on Twitter, Facebook, and elsewhere. For example, Binyamin Applebaum, a Washington correspondent for The New York Times, tweeted, “The Germans have stormed into a foreign country and taken charge. How unexpected.” Joshua Benton, director of the Nieman Journalism Lab at Harvard University, tweeted “Flush with Confidence, Germany Launches Land War in Asia,” while New Yorker music critic Sasha Frere-Jones tweeted “The Germans will just deny the match ever happened.” On Facebook, a post by British comedian Ricky Gervais—“This won’t be the first time thousands of Germans will have to lie low in Brazil for a while for their own safety”—drew more than 100,000 likes.

If this had been any other country playing, it is hard to imagine a similar outpouring of such borderline commentary. But when it comes to Germany, the usual rules of political correctness don’t apply. It’s always open season. In the popular imagination, behind every German even today is a goose-stepping Holocaust denier, or worse. In that regard, Germany truly is exceptional.

The spectre of Nazism has its obvious political uses. At the height of the Euro crisis, in 2010–11, a number of Greek newspapers and magazines published front-page photoshopped pictures depicting Angela Merkel in Nazi uniform or giving a “Heil Hitler” salute. It was much easier for the Greeks to remind themselves about the German occupation of their nation seven decades ago than to assume responsibility for the crisis they were going through, triggered largely by their own mismanagement and fraudulent economic statistics.

In its own way, each European nation has spun a narrative for itself out of that war, a narrative that has endured even as Europe itself has evolved. Charles De Gaulle made sure that the French saw themselves as victors and resistance heroes rather than as Petainist collaborators. The Dutch, Belgians, Danes, and others similarly cling to a postwar view of themselves that was constructed on the basis of their supposed (and sometimes actual) heroism under Nazi occupation. More significantly still, the key rationale for the creation of what is now the EU was that there should never again be a European conflagration. For young generations today, the idea of a war between France and Germany seems preposterous, but that doesn’t stop the mantra being repeated endlessly by European leaders in an effort to promote pro-European sentiment. It doesn’t work: the record of recent European elections is that the younger the voter, the less likely they are to vote. At the very least, that suggests a more updated and relevant rationale for the EU needs to be developed.

For the United States, too, it wouldn’t be hard to construct an argument as to why World War II continues to obsess policymakers and the public: after all, here was a conflict with clearly defined heroes and villains, a war with a happy and heroic outcome, an engagement that fully justified the decision to engage. A war, in other words, very different from Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan and others fought in the 70 years since.

The Third Reich and the Holocaust remain central in school curricula across Europe and in the United States—a morality tale about good and evil that sometimes drowns out the teaching of other periods in history. They are also ever-present in popular culture, from the 1960s TV comedy “Hogan’s Heroes” (which was a big hit in Germany itself) to Quentin Tarantino’s 2009 film “Inglourious Basterds,” to a huge range of comic books and video games.

One side effect is that the barbarity of the Holocaust and the abject suffering of people during World War II risk being debased and trivialized by the overuse of Nazi comparisons, not just in relation to Germans but in general. Especially online, conversations can quickly degenerate into slanging matches between two parties accusing one another of being Nazis. This is “Godwin’s Law of Nazi Analogies,” devised by Internet expert Mike Godwin, which postulates that as an online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Nazis or Hitler approaches one. Abraham H. Foxman, director of the Anti-Defamation League, for one, frequently speaks out again this sort of misuse of Nazi references, which he says banalizes the memory of the victims.

How many generations must pass before the shame of people at the actions of their forefathers loses its impact?

The Germans themselves have increasingly confronted their past head on. The state has paid out billions of dollars in reparations over the past 40 years. German children today are the third and sometimes the fourth generation to visit concentration camps and to learn at school the graphic details of the barbarity committed by their grandparents and great-grandparents. Germany’s economic and business leaders, too, have made major efforts to cast light on corporate involvement in the atrocities. Since the late 1980s, companies including Daimler, BMW, Volkswagen, Deutsche Bank, and insurer Allianz have commissioned professional historians to write up the unvarnished history of their activities and complicity during the Third Reich, including the widespread use of slave labor. In 2000, several thousand companies set up a foundation that paid reparations to remaining victims.

It’s easy to dismiss these efforts at atonement as too little and too late. Certainly, they can never detract from or make good the atrocities that were committed. But German penitence stands in stark contrast to the perceived indifference of the Japanese in relation to their wartime past, an attitude which infuriates China, Korea, and other Asian nations that experienced the hardship and brutality of Japanese occupation. And today, these German attempts to make good pose a difficult moral and philosophical question: how many generations must pass before the shame and guilt of people at the actions of their forefathers lose their impact?

ONE ISSUE OVER THE PAST YEAR, more than any other, has confirmed that President Gauck might be right when he says that Germany is now sufficiently self-confident to shake off its international dwarf status. That issue is the disclosure of the extent of spying on Germans by the United States.

That Chancellor Merkel would be upset by the discovery that the National Security Agency had tapped her mobile phone is not surprising. Like President Gauck and some other prominent German politicians, she grew up in the police state that was the former East Germany, and thus is particularly sensitive to any type of surveillance. That her irritation was compounded by the discovery that the CIA was recruiting German intelligence officials is also not shocking.

What jumps out, however, is the reaction. Merkel didn’t just complain to President Obama, she made a rare public fuss, describing the surveillance as “totally unacceptable.” Her government pushed Washington for Germany to be placed on the same top tier of intelligence partnership as historic partners Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom, and it expelled the CIA’s Berlin bureau chief. According to leaked government documents cited by the German newsweekly Der Spiegel, Berlin also considered applying other pressure on Washington, including halting all official government contacts for several weeks. In August, the same newsweekly revealed that German intelligence itself has been spying on others, especially in Turkey, but that it also picked up some of Hillary Clinton and John Kerry’s phone conversations.

This is assertive behavior not usually associated with Germany in general, and certainly not in its relations with the United States, which since 1945 have been acquiescent bordering on obsequious. Several German officials have told me privately that they think President Obama has failed to understand the depth of feeling in Germany and the damage that this affair has done to U.S.-German relations. Whether or not that’s true, the unmistakable sound coming out of Berlin these days in relation to the United States is the thud of Merkel putting her foot down.

It’s too early to say whether Berlin will from now on act far more forthrightly in its dealings with Washington, but here too the signs indicate that Germany’s self-imposed dwarfdom may be a thing of the past.

* * *

Peter Gumbel, a Wilson Center Global Fellow, is an award-winning journalist and author based in Paris. He spent 16 years at The Wall Street Journal, has worked as a senior writer for TIME, and served Europe Editor for Fortune Magazine. His latest book, France’s Got Talent, on France’s oppressive culture of elitism, was published in 2013. More of his work can be found at PeterGumbel.com.

Cover illustration by Zack Stanton, inspired by the cover art for “Er Ist Wieder Da.”