Winter 2018

For Ukraine’s Wartime Fact-Checkers, the Battle Rages On

– Lydia Tomkiw

From the fabricated crucifixion of a toddler to claims of fascist rule, Russia’s war in Ukraine continues not only on the battlefield, but in the information sphere. So, too, does the work of StopFake, a team that has seen Moscow develop the tools it has exported westward.

A tall, broad-shouldered volunteer soldier with a Cossack-style mustache, Maksym Aleksyeyev sits across from me in a café in the Ukrainian city of Lviv, hundreds of miles west of the warzone. He recounts a story from his time on the frontline, where he and other volunteers had headed to support the army in battling Russian-backed separatists:

It was his birthday that day, and he and his friends were allowing themselves to cheat on their promise to abstain from alcohol while fighting. Just as they were about to raise their shot glasses, Aleksyeyev recalls, his phone rang. His sister, Lena, was calling from Moscow. On speakerphone, she wished him a happy birthday and said she was praying for all of the boys – as well as for Russian President Vladimir Putin. There they were, on the frontlines, willing to risk their lives to defend their country’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, and his sister was toasting the very man who wanted to see them all destroyed. When he hung up, Aleksyeyev remembers, his fellow soldiers were more than incredulous.

Aleksyeyev tells me that his father had lived in Ukraine for years and had seen firsthand what the country and its people are like, but that his views had “cardinally changed” since the onset of war – and the onslaught Russian fake news.

“I have this contrast,” he says of his life, taking a long drag of his cigarette. Born to a Ukrainian mother and a Russian father, half of his family lives in Moscow. Russian media, he says, has convinced them that Ukraine is full of fascists, a line that state-owned television has pushed since the Euromaidan revolution more than four years ago – and an insult his father leveled at him when he decided to take up arms. Aleksyeyev tells me that his father had lived in Ukraine for years and had seen firsthand what the country and its people are like, but that his views had “cardinally changed” since the onset of war – and the onslaught Russian fake news.

Over the past year, the United States and Europe have seen, in increasingly stark relief, the potential of Russian propaganda and disinformation to sway public opinion. In Ukraine, the phenomenon is hardly new. And while generations of Ukrainians had been fed a steady diet of Soviet propaganda, Russia has used revolutionary Ukraine as a testing ground for its modernized disinform-and-divide tactics.

Fascists and Crucifixion

The revolution born on Kyiv’s Independence Square, or Maidan, began in late 2013, instigated by then-President Viktor Yanukovych’s volte face on a promise to sign an Association Agreement with the European Union. The Agreement, many hoped, would have placed Ukraine on a path toward the West and away from Putin’s pull. The revolution was soon followed by the Russian annexation of Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula and the start of war in the eastern, predominantly Russian-speaking Donbas region. The country’s ethnic, identity, and language differences had long been thorny issues, especially in the eastern regions. At the time of the revolution, Russian media was an established, often dominating force in the country, and was well-positioned to apply increased pressure on societal rifts.

By early March 2014, Russian propaganda was zeroing in on the treatment of Russian-speakers with a steady stream of fake news, falsely reporting, for example, that politician Oleh Tyahnybok of the nationalist Svoboda Party wanted the Russian language banned in the country and a prohibition on Russians’ becoming citizens. In television, online, and in print, Russian media was quick to label protesters and politicians as Nazis and fascists, portraying the far right of Ukraine’s political spectrum as the mainstream. Many reports even claimed that the revolution was a CIA-backed coup, something Putin echoed, in allusions and inferences, as recently as last summer.

It is perhaps the “crucified boy” story, however, that has come to signify the worst of Russia’s tall tales. Russia’s state-controlled television monolith, Channel One, reported in 2014 that Ukrainian soldiers in the eastern city of Slovyansk had crucified a three-year-old boy in front of his mother in the center of town before tying her to a tank and dragging her through the city. Reporters from Ukrainian, Western, and even Russian publications went to Slovyansk, but could find no one who had seen or heard of the incident. Even locals who admitted to hating the Ukrainian government told The New York Times that the story was “a grotesque lie” that no one had heard of until the Russian report.

Refutation of such stories notwithstanding, Russia had managed to sow confusion and cast doubt on the behavior of Ukrainian politicians and soldiers. The barrage of disinformation also provided a wealth of “evidence” to help Moscow justify its takeover of Crimea and its proxy war in eastern Ukraine. However, it also catalyzed a group of Ukrainian students, academics, and journalists into action.

Report a Fake

The project known as StopFake began nearly four years ago in Kyiv’s Podil neighborhood, an area dotted with hipster bars and restaurants. Several professors, journalists-in-training, and alumni from the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy had gathered to brainstorm. They knew a response was needed to counter the spread of fake news and felt that they could mount it. What they created is the only organization that has continuously, directly worked to counter fake news in Ukraine since the war began.

Launched in March 2014, the project began by debunking misattributed photos (such as those purporting to show dead children in eastern Ukraine that were actually photos from the war in Syria), misattributed videos, social media rumors, and invented news (such as the reported appearance of American mercenaries from Blackwater in Donetsk). Unlike Politifact in the United States and other sites that test the accuracy of statements made by politicians, StopFake focused primarily on sham news from Russia. Its main funding came through PayPal donations and its audience included Ukrainians from across the country.

When I first met the team of eight in June 2014, their nascent website was already gaining traction and a weekly anchor-style video broadcast reviewing the week in fakes was racking up views on YouTube. In one instance, they reviewed a photo that supposedly showed a morgue full of dead bodies in Slovyansk, an apparent attempt to illustrate the brutality of the war and of the Ukrainian forces. In truth, the photo was taken by an Associated Press photographer five years earlier while covering the drug wars in Mexico. In another, they examined Russian reports that the beaches in Crimea were packed with tourists only months after annexation, exemplifying how much better things were after casting off Kyiv’s yoke. In reality, tourism to occupied Crimea was down.

Debunking photos often wouldn’t take much time – usually a reverse image search through Google and a few minutes writing a post to point out the contradictions and false attribution. Disproving other stories meant calling government agencies and verifying statistics and quotes to check against those cited by Russian media. The “report a fake” button in the upper right-hand corner of the website supplied plenty of fake news leads, as it continues to do today, says StopFake co-founder and journalism program Director Yevhen Fedchenko.

In the spring of 2014, the project had some 60,000 followers on social media. Fast forward to today, when StopFake has more than 185,000 followers and likes on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Russian networking site VKontakte, and other platforms. (The increased digital attention also means the website faces DDoS attacks, trolls, and hate comments.) The StopFake News program is now broadcast on 8 TV channels across Ukraine and the team also produces Russian-language radio digests that reach areas not under the government’s control.

“We never thought or planned for the project to last for three years or four years. Truthfully, I thought it would last a few months,” says Ruslan Deynychenko, a journalism professor and StopFake’s other co-founder. He sits in the same spot where the project was born, now the work space of 30 volunteers, including students, locals, and some individuals from abroad.

Indeed, the international footprint of StopFake is growing, too. It now hosts versions in 11 languages and has added fact-checking of reports from other countries. StopFake has been following Russia’s pattern, Fedchenko says, adding new editions when an uptick is observed in Russian-sponsored news in a particular language. After noticing a growing number of news items in 2017 around conflicts regarding Polish-Ukrainian history, he tells me, a Polish language version was added. According to analytics, StopFake’s highest readership is in Ukraine and Russia, followed by the U.S., Germany, and Italy. Fedchenko points to high Russian readership as a sign that Russians, too, are searching for truth.

Debunking (and Bingo)

But according to Deynychenko, the growth of the initiative has also been necessary to address the fact that work has become more complicated. Russian propaganda has backed away from the blatant lies that are easy to disprove with a quick Google search and is now increasingly mixing truths with fakes to sow confusion, he says:

“[Fakes] have become smarter, more professional. Russian propaganda had many stories that after 15 minutes you could look over and show that it was a complete untruth… Now, they are mixing half-truths, manipulation – so to not repeat stories like the crucified boy.”

What began as a basic fact-checking operation has evolved into a large-scale example of how to analyze and unpack fake news.

That means more in-depth debunking work, giving context to stories where truths are interwoven with lies. What began as a basic fact-checking operation, then, has evolved into a large-scale example of how to analyze and unpack fake news.

At the same time, revealing falsehoods and holding Russian reporting accountable has not stemmed the tide. “The persistence with which they push, that is what is amazing, because we debunk and then the next week they push the same story, sometimes even through the same channel,” Fedchenko laments. “It’s just to make sure that it will be all over Google and social media, because they know they need to pollute the media system with nonsense.”

And so he and his colleagues debunk the story again.

StopFake is also employing a novel, not-so-novel technique: use of the print medium. At the start of 2017, the project launched a monthly Russian-language newspaper that is dropped off in Kramatorsk, where Ukrainian television and radio often do not reach. Front-page headlines, mostly about debunked headlines, appear below the slogan “It’s your right to know.”

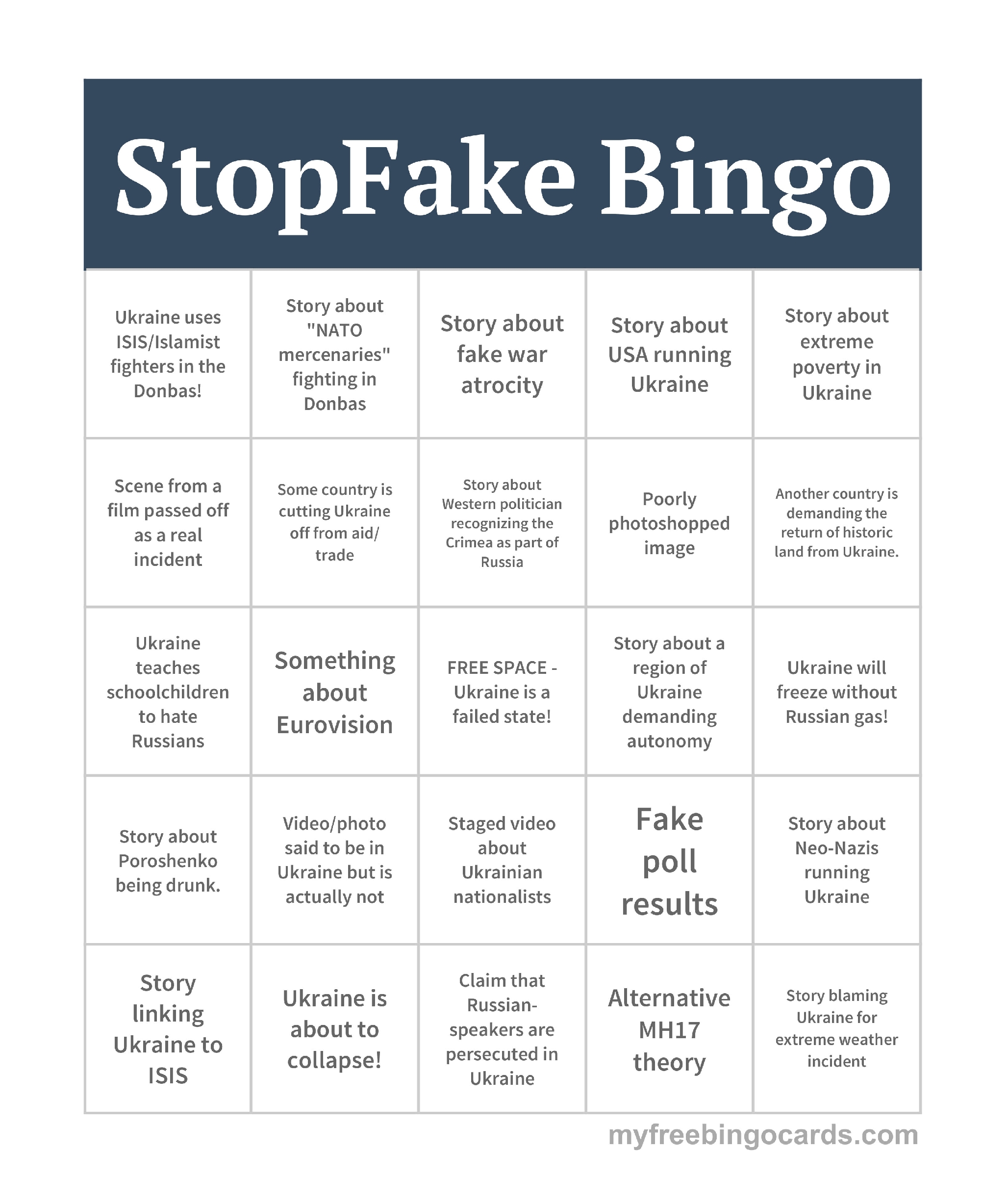

StopFake has also expanded its mission to include training and education. The team has developed a textbook on media literacy, a training course for other media outlets, and a manual for professors who want to teach fact-checking. Journalism teachers from 10 universities across Ukraine have been trained. StopFake also released a documentary, Nothing But Lies, that explores the fake news phenomenon. The website also provides detailed guides on how to spot fake videos and photos as well as a test that allows users to see how well they can distinguish fact from fabrication. (Did former U.S. Vice President Joe Biden call Ukraine the world’s most corrupt country? Fake news.) There’s even a StopFake Bingo game with common Russian fakes about Ukraine. (Place an X over a poorly Photoshopped image or a scene from a film passed off as a real incident.)

How effective have StopFake’s efforts been? While pointing to the healthy analytics, its co-founders concede that direct impact is difficult to measure. Nonetheless, a survey they commissioned in 2017 showed that 58 percent of Ukrainians believe Russian propaganda poses a threat, a figure Fedchenko thinks would have been much lower before the war – and before awareness-raising.

When it comes to funding, co-founder Deynychenko says the project will never take money from the Ukrainian government, not wanting to be seen as one nation’s propaganda fighting another’s. According to its website, the initiative runs on donations and grants from foreign foundations and governments, including George Soros’s International Renaissance Foundation, the Sigrid Rausing Trust, the British Embassy in Ukraine, and the Foreign Ministry of the Czech Republic.

A Different Frontline

While generally applauded by media freedom groups and human rights organizations, StopFake has also taken some positions that have garnered criticism. During the past year, the Ukrainian government deported several Russian journalists on grounds of spreading anti-Ukrainian propaganda and also banned popular Russian social media sites, including VKontakte and Odnoklassniki. Both are moves that StopFake supported.

Conversely, when Ukrainian authorities deported Anna Kurbatova of Russia’s Channel One in August 2017, Human Rights Watch called the move “a serious violation of [Ukraine’s] international human rights commitments.” The Committee to Protect Journalists said, “Ukraine is in an information war with Russia, but singling out reporters for retaliation is not the means to win it.”

Fedchenko disagrees: “We do not consider [Kurbatova] to be a journalist... Journalism is about fact-based storytelling, not about fake-based lies. So, we do not see Channel One or RT or Sputnik as media organizations. Therefore, our approach is that they should not have the privileges of media organizations… Propaganda is not simply freedom of speech.”

“Have I gone to the frontlines? No. Do I give enough money to support them? No… Otherwise, I wouldn’t be able to look myself in the mirror – that’s why I’m sticking with it for so long.”

Margo Gontar, StopFake’s Russian-language anchor, exudes a similar level of passion. Speaking to me at a café a few steps from Kyiv’s Maidan, she says this is the longest job of her career. “Have I gone to the frontlines? No. Do I give enough money to support them? No… Otherwise, I wouldn’t be able to look myself in the mirror – that’s why I’m sticking with it for so long,” she says.

She also questions how long it will take for a new international understanding and set of rules to emerge about “how to distinguish where freedom of speech ends and where information-influence starts.” It’s an issue governments are grappling with at this very moment.

The StopFake staff tells me that they have actively watched disinformation campaigns in other countries, in particular during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Fedchenko warns that Russia was able to build a fully operational system in Ukraine that can now be moved from country to country as needed, forcing nations to decide how they will respond.

“It’s a question of how much each country, each government, wants to know of these activities happening on their soil, because for them it is always a dilemma,” he says. “Either you call a spade a spade, and then you definitely need to answer those challenges – and those answers might be quite unpleasant and might even ruin relations with Russia – or you can pretend and [leave it at] ‘Yeah, something probably happened, but we don’t care much.’”

For its part, StopFake has no plans to stop calling a spade a spade. That’s a key part of its message for foreign journalists: fake news does not rest, so neither can you. In the case of Ukraine, observers are anticipating an aggressive wave of fakes to coincide with the 2019 presidential election. Meanwhile, the war in the East has no end in sight, with many analysts assessing that Russia’s goal is to keep the region, if not the country, perennially unstable.

For Deynychenko, as for many of the others behind StopFake – and just like the Maksym Aleksyeyevs of the country – the problem also has distinctly personal manifestations. In his own family, his wife has stopped talking to her cousin in Moscow. It’s another relationship disrupted by the war, and, he believes, by Russian disinformation. And so, his battle rages on.

* * *

Lydia Tomkiw (@lydiatomkiw) is a reporter and editor who focuses on international affairs and finance. She has reported from Ukraine for The Christian Science Monitor, the International Business Times, and the Nieman Journalism Lab.

Cover photo courtesy of Flickr/Ukrainian Ministry of Defense