Summer 2014

From Flames to Fury

– Carol Burke

The 2011 burning of a sacred Quran in Florida provoked a deadly, little known, and massively misunderstood maelstrom in Afghanistan.

In July of 2010, Terry Jones, the pastor of a congregation of fewer than 50 members in Gainesville, Florida, threatened to set ablaze 200 Qurans on the anniversary of September 11, 2001. After pleas from President Obama, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, General David Petraeus (who was Commander of Forces in Afghanistan at the time), and religious leaders across the globe, Jones backed down.

Unfortunately, he was not dissuaded for long. The proposed building of an Islamic community center near Ground Zero in lower Manhattan reignited Jones’ zest for publicity and his zeal to perform the act of desecration that he had temporarily put on hold. He declared that March 20, 2011, would be “International Judge the Quran Day,” a day in which the holy book would be put on trial and, if found guilty, executed. In anticipation, Jones claimed that he had taken a poll of hundreds to determine the fitting punishment for the Quran should it be convicted at the trial. These ideas included drowning the holy book and death by firing squad, but the hands-down favorite among Jones’ online followers was setting the sacred text ablaze.

On March 20, after a six-hour trial in which Jones played the part of judge, he pronounced the book guilty of “crimes against humanity.” Because he had appointed himself judge, Jones later explained, he could not also act as executioner, so he called on one of the 30 church members who had witnessed the trial to place the kerosene-soaked text, sacred to 1.5 billion Muslims, in a $79 portable fire pit.

With a spark from a plastic barbeque lighter came the fire that would produce plenty of shock but little awe in Muslim communities throughout the world, especially in Afghanistan. In contrast to the media coverage lavished on Jones when he first threatened a bonfire of Qurans, the American press displayed uncharacteristic restraint by refusing to publicize the incident.

With such limited coverage, how did the news spread through Afghanistan? Al Jazeera had broadcast several reports of this off-again-on-again story, but its reporting was quite balanced: a threat from Jones followed by a denunciation from Obama or another prestigious critic. Oddly, a statement by Afghan President Hamid Karzai broadcast on all the Afghan TV and radio stations on March 24 was the first that many Afghans had heard about the Quran burning.

Karzai condemned Jones’ act and called for American authorities to arrest the “infidel.” In turn, Karzai was criticized in the West for helping to fuel the flames of anger against America. Whether Karzai was using the opportunity to curry the favor of the religious right in his own country or whether, as the leader of an Islamic nation, he felt bound to stress the seriousness of this insult, his condemnation alone would not have precipitated the tragic events of April 1 and April 4 in northern Afghanistan.

At the time, I was serving as cultural advisor to the commander of the U.S. Army brigade headquartered in Mazar-i-Sharif, but on April 1, I was not at headquarters. Instead, I was 200 miles west of Mazar at the U.S. Army base on the outskirts of the small city of Maimana in Faryab Province.

The first violent reaction to the Quran burning was precipitated by a reactionary Sunni religious leader named Mawlawi Abdul Qahir Zadram, who incited an aggressive demonstration during Friday prayers on April 1 at Mazar-i-Sharif’s Blue Mosque, the famous shrine to Hazrat Ali (Mohammad’s warrior son-in-law, Muslim caliph and, according to some, one of the scribes who recorded the Prophet’s revelations into what would become the Quran). Zadram and other conservative religious leaders incited worshipers, angry at the news of the Florida Quran burning, to march to the nearby headquarters of the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA).

Determined to do more than peacefully demonstrate their outrage, a small group within the larger protest — including several supposedly former insurgents who had renounced their past and were living at a government safe house — attacked and killed the four Nepalese guards on duty that day at UNAMA along with a Swede, a Norwegian, and a Romanian. The only male UNAMA staff member present at the courtyard who was not killed was one who recited the shahadah, the fundamental statement of belief by Muslims that there is but one God and that Mohammad is his prophet.

A female UNAMA employee who witnessed the attack said that there was no doubt that it was well organized. Shortly after the tragedy, Balkh Provinicial Governor Atta Mohammad Noor announced the arrest of 30 people, seven of whom, he said, were known members of two powerful insurgent groups: Hezb-i-Islami and the Taliban.

Why was UNAMA targeted? In the days after the April 1 killings I asked more than 50 Afghans (some illiterate, some literate, others college educated) if they knew what UNAMA was doing in Afghanistan. Nobody did. They believed that it was an American organization and was, therefore, targeted after the Quran burning. Ironically, UNAMA’s main goal in northern Afghanistan was the prevention of civilian casualties, and when they did occur, their investigation and subsequent reporting.

Joakim Dungel, a 33-year-old Swedish human rights lawyer who had worked on the war crimes tribunal at the Hague, was a recent addition to the UNAMA staff. I had worked with him to brief female soldiers training to become members of female engagement teams. Dungel taught them about the United Nation’s role in this region of Afghanistan, and I instructed them in the cultural differences they might encounter.

On March 28, three days before the attack, Dungel had flown out to northwestern Afghanistan, where he and two other UNAMA workers investigated the recent death of an Afghan civilian. I was impressed with the tough questions they posed to the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) military commander’s executive officer in whose area the death had taken place. Shortly after, Dungel returned to Mazar-i-Sharif and on April 1, became a civilian casualty himself. The final death toll from the violent protest in Mazar-i-Sharif was 17. Ten Afghans were killed at a similar protest in Kandahar.

Most of us at the U.S. Army base in Maimana felt far removed from those Friday demonstrations and the violence they precipitated. After a weekend of receiving updates on the events in Mazar, the lieutenant colonel in command (an officer I have decided not to name for his protection) prepared to head to the center of the city for a meeting with officials at the headquarters of the Afghan Border Police.

A former Lacrosse player for West Point, he was more comfortable in his workout gear than in his military uniform, his “multi cams.” The large flat screen TV in his office was always on, and even when there was no one there to listen, it was always turned to ESPN. With a coach-like lingo, I heard him instruct subordinates to “find the likely courses of action so we’re not just spitballing,” and when they did, to “get fuckin’ hot.” Talking about the threat of insurgents, he said to his soldiers, “We need to get them while they’re in the locker room before they come back for the second half.”

On that sunny April 4th Monday, three days after the murders in Mazar, the distant western hills green from the runoff of melted snow, the lieutenant colonel jumped into the passenger seat of one of the battalion’s massive $650,000 Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected vehicles (MRAPS), designed with v-shaped hulls to withstand Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs), a major killer in this war. He joined a small convoy that would taxi him the few blocks to downtown where he would engage in a routine meeting with local leaders.

The big vehicles lumbered through the city’s colorful bazaar, down the streets I had traveled many times, where shop owners displayed their wares: gold jewelry, televisions, and dentures. The more modest shops set out their furniture, stacks of colorful tin trunks, canned goods, traditional men’s clothing (what soldiers referred to as “man jams”), the Western attire of jeans and backpacks, wedding decorations, hardware, produce, fresh baked naan, almonds, pistachios, and raisins from the neighboring farms. Each morning as the butchers were hanging their freshly slaughtered meat on their stalls, a governmental official with a bullhorn walked through the bazaar announcing the fixed price per kilo of lamb, chicken, and beef — a holdover from the days of Soviet influence. Although the government’s intent was to keep it affordable, everyone knew that the butchers would charge whatever they could get because the government enforcer was paid off with a loin of this or a brisket of that.

This small northwestern city was regarded as safe and was thus considered a “soft-hats city” by the battalion. After all, the American base hadn’t been fired on in seven years, and residents seemed to appreciate the paved roads and streetlights brought to them by American taxpayers. It seemed a long way from the anger that had raged just three days earlier in Mazar-i-Sharif.

There was nothing out of the ordinary about the commander’s meeting with leaders of the Border Police at their downtown compound that day. He met regularly with the heads of the local Border Police, the National Directorate of Security (Afghanistan’s intelligence organization), and the Afghan National Police to discuss security threats in the area. I sometimes accompanied him and his predecessor on these routine visits, but on this Monday I was on base finishing a report. Some of his soldiers guarded the vehicles left on the side of the street, others went inside with him, and two sergeants stood guard outside the building.

Suddenly, without warning, one of these sergeants was shot in the head and the other in the neck. The deaths of these seasoned soldiers who had survived previous deployments in Iraq made it tragically clear that attitudes had changed, and that the high profile Quran incident in Florida had sparked far-reaching anger that would not subside any time soon.

After the bodies of the American service members were evacuated, the Afghan Border Police commander called roll. The only person who didn’t answer was a man named Samaruddin.

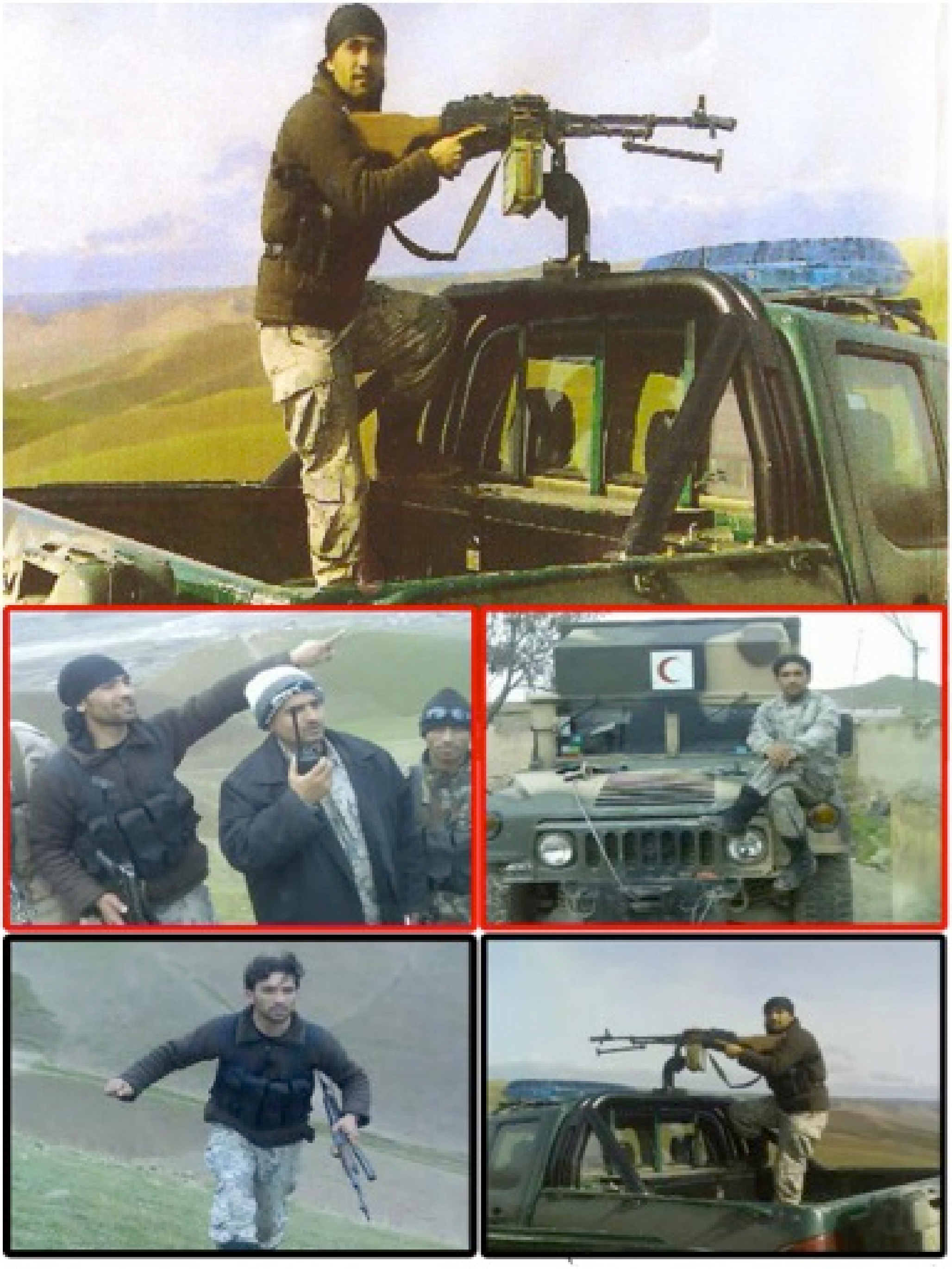

The head of the Afghan Border Police and the commander of the American battalion both believed that this handsome young member of the force, a trained sniper, was the assassin who had taken aim from his elevated guard position, shot and killed both Americans, dropped his rifle, and fled. The deaths of the two American soldiers and the name of their assailant were published, but nobody followed up to report the developments in the weeks after the shootings.

In under 36 hours, Samaruddin was located sleeping in a car at the residence of Shahazada, a reputed crime boss who, locals alleged, had ties to powerful government figures, a fact that counted for little when the mission was to hunt down the killer of two American soldiers.

The next day, the governor of Faryab Province announced to the media that a small group of Afghan commandos had found and killed Samaruddin, an account intended, no doubt, to give the Americans cover, but the story failed to convince local residents. Eyewitness reports spread throughout the city that the assassination had been an American operation.

From conversations with Army officers and local Afghans, I was able to piece together what had happened. After learning that Shahazada had given Samaruddin what the fugitive thought was safe haven, the American brigade commander and a small group of soldiers went to Shahazada’s home, approached the car Samaruddin was in, and ordered him to exit.

When he finally did emerge, Samaruddin allegedly came armed with a knife and he was quickly shot and killed. The American officer conducting the subsequent investigation likened the death of Samaruddin to what police officers in the U.S. call “suicide by cop,” the violent death of a suspect who refuses to be taken alive.

The morning after the raid that had resulted in Samaruddin’s death, I saw an Afghan Border police jacket hanging on the coat rack in the American brigade commander’s office — a trophy that proved that justice had been delivered. But while the American story surrounding the incident may have ended, the Afghan saga was just beginning.

At Samaruddin’s funeral, hundreds gathered to protest the American presence in Afghanistan and to praise Samaruddin’s pious revenge for the burning of the Quran. The protests continued for weeks, and, according to local residents, insurgent recruiters from as far away as Uzbekistan began using them to recruit young unemployed men to their cause. One local resident told me, “Before the killing of Samaruddin, 80 percent of the people were pro-ISAF [International Security Assistance Force] and 20 percent were opposed; now it is the opposite.”

Within days, different versions of the Samaruddin martyr posters littered shop windows in a city 40 miles away. A week later, they were visible in the marketplace in a small village 110 miles away. Cell phone stores sold videos about the martyr’s life and death, and Afghans downloaded his photo onto their phones.

Some local residents believed that Samaruddin was a lone wolf who in the aftermath of the Quran burning wanted some justice for all Muslims and so took out his righteous indignation on the two American sergeants. Others, mainly Uzbeks, insisted that although Samaruddin was enraged about the Quran and wanted to retaliate against the Americans, he was acting on behalf of the alleged criminal leader, Shahazada. They even speculated that there was an Uzbek-Tajik struggle behind it.

Relations between the two major ethnicities in the area had always been tense, and five years earlier they were killing each other in the streets. Shahazada, a Tajik, had in the past been incarcerated for crimes of murder and kidnapping but always managed to get out. Many believed that his connections to those in government, leaders in Mazar-i-Sharif and Kabul, would secure his freedom no matter what heinous crime he committed. Although many locals were willing to talk about these issues with the Americans, nobody was listening; the Americans believed there was nothing left to discuss.

Religion infuses every aspect of life in Afghanistan — I saw this firsthand. In areas far from headquarters, religious leaders inform those in their villages not only on religious matters but on political matters as well. They sit on local shuras, the only viable rule of law in many districts, and help resolve disputes. In an election, they advise villagers on how to vote and persuade people how to view the foreign occupiers and the local insurgents. The Soviets tried to ignore the importance of religion during their nine-year occupation of Afghanistan in the ’80s, and so it seems did the U.S. in this latest war. The majority of insurgent leaders in Afghanistan preface their names with “Mullah” or “Malawi,” signifiers for Muslim clerics, but our ardent secularism prevented us from seeing the virtue of religious engagement.

In Mazar-i-Sharif, the American military spent nearly $600,000 of American taxpayer money to improve the Blue Mosque, the site from which the protesters launched their tragic assault on the UNAMA headquarters in early April, 2011. If expensive Herat tiling didn’t buy us any good will, then what could have?

We knew that simple mosque kits (which included carpeting and a speaker system to broadcast the call to prayer five times a day), available to any military unit within two weeks, could make an extraordinary impression. In one volatile area, a 10th MTN Battalion commander gave a mosque kit to a poor village and began an effective relationship with the local mullah, the elders of the village and the tribal leaders in the region.

However, there was little consistency. What one unit was willing to do, its successor was not. After the 10th MTN returned home in February 2011, a less experienced unit replaced them in one of the two most volatile districts in the north. This new unit’s commander had little interest in engaging religious leaders in the area, so three of the four mosque kits the 10th MTN had ordered remained in a tent on base despite the offer from a respected elder and secular leader to help distribute them.

‘We failed to explain how un-American it is to burn anyone’s holy book’

Although we invested millions in the big projects, we missed the small opportunities that even the Army’s own Counterinsurgency Field Manual touts as chances to change attitudes for the long run. We failed to explain to local religious leaders how un-American it is to burn anyone’s holy book, and we failed to tender a meaningful apology for the action of a single American who was more interested in spreading his incendiary message than engaging in meaningful exchange. Tragically, the vicious cycle continued.

On February 20th, 2012, American soldiers in Afghanistan disposed of Qurans from the prison at Bagram Air Base by throwing them into a burning trash pit. When a couple of local Afghans working nearby discovered what was being done, they yelled for the soldiers to stop and reached into the fire to pull out the singed texts. Gen. John Allen, the ISAF commander in Afghanistan at the time, apologized the next day and announced that he had ordered an investigation into the incident and vowed that such desecration would not happen again.

Then-Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta also apologized, and on February 23rd, his Deputy Defense Secretary, Ashton Carter, met with Afghan leaders in Kabul and delivered a written apology from President Obama assuring the leaders that the desecration of the Qurans was “inadvertent” and that “we will take the appropriate steps to avoid any recurrence, including holding accountable those responsible.”

Although President Karzai called for restraint when the incident first became public, he later referred to the Quran burning as a “Satanic act” and advocated a 2013 withdrawal of all foreign troops, a demand he later retracted. He did, however, appoint a group from the Ulema, a body of Muslim legal scholars, to conduct its own investigation into the Quran burning. Afterward, the Ulema refused to accept the apologies offered by the President and U.S. military leaders for what these clerics characterized as an “evil act” that warranted a public trial.

The Taliban also rejected the apologies, claiming that such words were mere “show,” and they called on Afghans to take revenge until “those who do such inhumane acts are prosecuted and punished.” They encouraged Afghans to attack foreign bases and convoys, and to kill and beat soldiers as a lesson so that they would never again “dare to insult the holy Quran.” That call was heeded, and the two weeks following the February 2012 Quran burning were plagued with widespread demonstrations, violence, and death.

—

In Afghan culture, apologies for offenses committed against others enjoy a long history. Grievances are brought before local jurgas or shuras, which function like juries; they hear both sides and determine not only if a wrong has been committed but who is at fault and what the guilty party should do to make the victim whole again. It’s a criminal and civil system rolled into one and an effective antidote to the fierce eye-for-an-eye-style honor code that once prevailed. It is only the new Western-style legal system (bought and paid for by Western funds and riddled with corruption) that fails to acknowledge the role of apology in Afghanistan.

We know from recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan that toppling a regime in power can be accomplished more easily and more swiftly than the insurgency that can follow. We defeated the Taliban in a matter of weeks. For 13 years, we have tried to win a protracted war of counterinsurgency, America’s longest war, one in which religion plays a starring role.

Our Western secular bias sometimes blinds us to the power of religion and how it defines the enemy we seek to subdue and the populace we seek to protect — until all we have left is a hollow apology to offer. As one familiar Afghan proverb goes: “Avoid what will require an apology.”

—

Carol Burke, Ph.D. is a professor at the University of California at Irvine who teaches journalism, film and literature. She has documented her ethnographic work in books about the lives of Midwestern farm families, female inmates in our nation’s prisons, and most recently in Camp All-American, Hanoi Jane, and The High-and-Tight: Gender, Folklore, and Changing Military Culture.

Cover image courtesy of Steven Weissman

This story was created in partnership between The Wilson Quarterly and Narratively