From Hell to Hope: Rwanda and the DRC

– Jeff Roquen

After a generation of life and death since the genocide, Rwanda has been socially reconstructed from top to bottom.

For most people, it seems like yesterday. For the people of Rwanda, yesterday is today and tomorrow.

By the spring of 1994, the world order held genuine promise for the first time since the end of the Second World War in 1945. The Soviet Union was defunct, Germany had reunified, and it seemed that Eastern Europe was on the road to democracy. The North American Free Trade Agreement had brought down trade barriers between the United States, Mexico, and Canada, boosting the world’s economy. Apartheid fell in South Africa, and Nelson Mandela would soon become his country’s first black head of state. Two thousand miles north of South Africa, in August 1993, the UN-sponsored Arusha Accords had brokered a cease-fire to the three-year civil war in Rwanda between the Hutu-dominated government and the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a Tutsi-controlled paramilitary force. As the bloodshed tapered off, the promise of peace and a future of shared power gave way to an uneasy hope.

On the evening of April 6, 1994, that hope died. That day, assassins in Rwanda launched a surface-to-air missile and downed the plane carrying President Juvénal Habyarimana (a Hutu) and members of his government. In most nations, such a loss would be an occasion for collective mourning, partisan divisions slipping away as everyone rallies to the flag. But Rwanda did not collectively mourn the loss of its leader. In any functional sense, there was no single Rwanda, but two nations within its borders: Hutu and Tutsi.

For the country’s middle-aged and elderly, memories of the 1959–1962 Rwandan Revolution were still vivid. After centuries of Tutsi domination, the Hutu majority had rebelled and seized power with the aid of their Belgian overlords. For some Hutus, power was not enough. It was time to exact revenge. In 1963, one year after winning national independence, the Rwandan Army conducted indiscriminate massacres of Tutsis in Nyamata, outside the capital of Kigali. Three decades later, the horror returned.

Days after the murder of President Habyarimana, Hutu authorities acted on the assumption that the assassination had been carried out by their longtime ethnic rivals. The Hutu leadership made a decision: the Tutsis would have to be eliminated once and for all. At one local gathering to organize the genocidal campaign, those who arrived without a machete or other killing instrument were berated by the Interahamwe, a Hutu paramilitary group. Once ready with their sharpened knives, the wholesale slaughter of innocents began.

Rwanda’s genocide was the first act of a long-term regional struggle for power. For central Africa, the atrocities were only beginning.

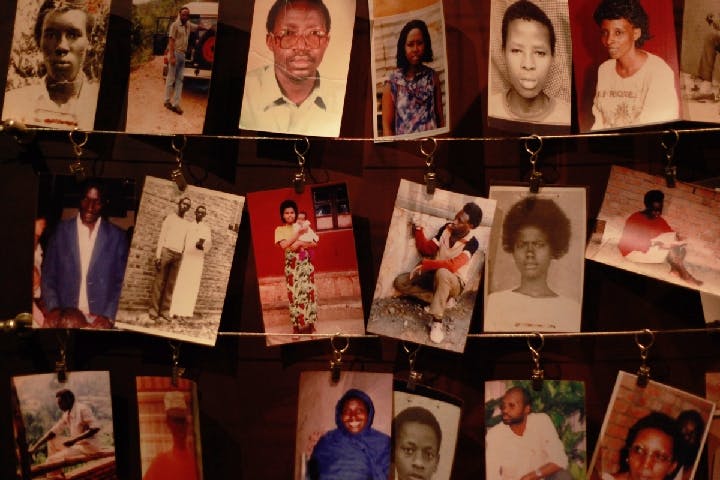

The memories of the murder victims are lost to the ages, but the public memory of the horror of their deaths cannot be laid to rest. The world mourns, the nation remembers, and the killers bear witness to the atrocities they committed. Those testimonies have been collected by, among others, author Jean Hatzfeld in her oral history of the genocide, Machete Season (2006).

We read the words of Fulgence, a Hutu, who clearly remembers his first victims: “First, I cracked an old mama’s skull with a club. But she was already lying almost dead on the ground, so I did not feel death at the end of my arm. I went home that evening without even thinking about it. Next day, I cut down some alive and on their feet. It was the day of the massacre at the church, so, a very special day. Because of the uproar, I remember I began to strike without seeing who it was. … I looked at the blade, and it was wet. … I had done enough. That person I had just struck — it was a mama, and I felt too sick even in the poor light to finish her off.”

For others, like Léopord, killing Tutsis was just another job: “Since I was killing often, I began to feel it did not mean anything to me. It gave me no pleasure. I knew I would not be punished; I was killing without consequences. … I left every morning free and easy, in a hurry to get going. I saw that the results were good for me, that’s all.” Thousands more Hutus rose up, just like Fulgence and Léopord. They killed innocent men, women, and children. They returned home when their work was finished, as if completing a routine day on the job. The killing went on month after month, and the world watched — and did almost nothing.

By the time the genocide ended in mid-July 1994, approximately 800,000 people had been murdered. Destroyed families, orphaned children, and millions of traumatized individuals littered the tatters of a broken nation. But Rwanda’s genocide was merely the first act of a long-term regional struggle for power. For central Africa, the atrocities were only beginning.

In June 1994, the tables turned. Under the leadership of Paul Kagame (the current president of Rwanda), Tutsi RPF forces recaptured most of the country. To escape retribution, approximately two million Hutus — including members of the Interahamwe — fled to the neighboring provinces of North Kivu and South Kivu in the far eastern portion of Zaire. With this Hutu mass migration, the genocidal civil war begun by the Hutus bled into an Africa-wide conflagration.

To eradicate the Hutu threat across the Rwanda-Zaire border, an invasion by the Tutsi RPF in 1996 not only reduced the capacity of the Hutu militias, but also served to destabilize and ultimately collapse the embattled regime of Zaire’s long-serving, corrupt strongman Mobutu Sese Seko. Instead of resolving conflict, this First Congo War (1996–97) allowed Marxist rebel Laurent-Désiré Kabila to assume power and rechristen Zaire as the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), while pushing the region further down a steep spiral of individual and state-sponsored violence. For the Tutsi-led Rwandan government, Kabila’s inexperienced regime proved wholly unable to rein in the still-operational Hutu militias in the east during his first year as the DRC’s head of state, and Rwanda and Uganda invaded in an attempt to overthrow this paper lion and onetime ally. Kabila, however, had allies with vested interests in his survival: forces dispatched by Angola, Namibia, and Zimbabwe swept into the DRC to counter the Rwandan and Ugandan designs.

Starting in 1998, the combatants of the Second Congo War fought for five long years over territory (and minerals) inside the defunct quasi-state. To finance their armed campaigns, the insurgents battled to control areas known for their natural bounty of gold, diamonds, and coltan (a valuable metallic ore used in a wide range of electronic devices, including laptops and mobile phones). After President Kabila was assassinated in January 2001, a series of peace talks from Gabarone in August 2001 to Pretoria in December 2002 led to a formal end to the conflict the following summer. Yet there was little joy in the suspension of hostilities. At least three million lives had been lost to mass violence, starvation, and disease. For the shattered survivors, desolation was the order of the day.

In the early 2000s, the cataclysm in central Africa mattered little to those living in other parts of the world. After the terrorist attacks of September 11, the voices of Western talking heads and policymakers largely drowned out news unrelated to the “War on Terror.” Day and night, media outlets bombarded populations with a Möbius strip of footage of the attacks on the World Trade Center; stock video of terrorist mastermind Osama Bin Laden; and, eventually, the newly declared public enemy number one, Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein. As the United States, the United Kingdom, and their reluctant allies mounted a quixotically disastrous campaign to bring stability and democracy to Iraq, low-level but high-intensity fighting continued in the eastern Congo between Hutus and Tutsis, despite the conclusion of numerous peace agreements. Indeed, the resentments and memories of the Rwandan Genocide of a decade earlier continued to lead men to commit unspeakable acts of brutality against innocent civilians.

Late at night in November 2012 in the town of Minova in South Kivu, DRC, a group of women, wartime rape victims who had congregated on a farm settlement for social, emotional, and economic support, were suddenly besieged by armed marauders. The attackers — members of the Tutsi-led M23 militia — raped many of the women again. For the soldiers who carried out these war crimes, their actions were sometimes justified through the barbarous logic of their superior officers. After losing ground on the battlefield or the setback of a failed campaign, commanders often condoned and even encouraged their units to seize women in order to boost morale. In a remarkable interview, one M23 soldier equated the rape and murder of innocent women to a form of liberation.

The M23 militia, an organization composed of former members of the National Congress for the Defense of the People, had been formed in 2006 to oppose Hutu control in the region. A 2010 analysis by U.S. researchers estimated that during the ongoing conflict in the eastern DRC, 48 women and girls were raped every hour. Few people noticed or cared. The headlines in the Atlantic world shouted about the European debt crisis, the still-lagging U.S. economy, and President Barack Obama’s attempts to extricate American military forces from Iraq and Afghanistan.

Human beings are, if nothing else, remarkably resilient when faced with desperation, despair, and death. Beyond the unquenchable desire for self-preservation, we survive the hardest times on an article of faith encapsulated in a single word: hope. Perhaps no one captured the essence and relationship of hope to humanity more than ancient Roman philosopher Pliny the Elder: “Hope is the pillar that holds up the world. Hope is the dream of a waking man.” In the twenty long, hard centuries since his time, human beings have survived by clinging to hope for the sake of their loved ones, their children, and future generations.

So it is in central Africa. After generation of life and death since the genocide, Rwanda has been socially reconstructed from top to bottom. Instead of the rigid and divisive distinctions between Hutu and Tutsi, Rwandans have deemphasized ethnic and clan-based designations for a more inclusive society. The transformation of Rwanda from a culture of resentment to one of respect and dignity is owed primarily to a once neglected group: women. Rather than men, it was women, including a large number of single mothers, who scratched, survived, and demanded equal rights for both their sons and daughters.

Human beings are, if nothing else, remarkably resilient.

After the genocide, men comprised only 30 percent of the Rwandan population. It was an opportune moment for the women of Rwanda to fill the leadership vacuum, and they did. Today, they participate and lead at nearly every level of society. For many Westerners, it could come as a surprise that Rwanda has the world’s highest proportion female representation in a popularly elected national legislature — more than the British House of Commons, more than the U.S. House of Representatives, more than Swedish or Danish or Canadian legislatures. Rwanda’s new leadership has effectively curbed public corruption, while the economy continues to expand rapidly (the nation posted a remarkable 6 percent growth in its gross domestic product in 2014). The fires of national hope have been rekindled.

After years of strife, a modicum of stability has returned to the DRC. Although rebel activity still exists in the far eastern region, the battlefield successes of the Congolese army in late 2014 decimated the ranks of M23, forcing its leaders to sue for peace in December. On the economic front, the DRC has grown at an impressive 7 percent or higher annually since 2010 due its vast mineral deposits — though a considerable portion of that wealth has been extracted and repatriated by large Chinese mining companies — and most of the population still consists of wage laborers or indigent land cultivators. All, however, is not bleak: between local and national leaders and a number of nongovernmental organizations, investment dollars are beginning to pour into the country to the benefit of impoverished communities. Indeed, the recent decision by Starbucks to begin buying coffee in mass quantities from the DRC has already significantly raised the incomes of coffee farmers in the coffee-rich nation. A reprieve has come to the Congo, and the dream of a peaceful future has returned.

In failing to halt the Rwandan Genocide, the First and Second Congo Wars, and years of postwar conflict in central Africa, the world watched as at least 5 million people perished and hundreds of thousands of women, children, and men were raped — sometimes repeatedly — over more than a decade. Consequently, it can be reasonably established that the so-called “international system” remains more of a myth than a reality.

Although nothing will atone for the blind eye that the world turned to the recent plights of Rwanda and the DRC, the international community can and must now contribute to the ongoing social reconciliation and economic revitalization efforts in both countries.

Anything less would be a crime against hope — and humanity.

* * *

Jeff Roquen is an independent scholar based in the United States.