Gaining Followers: The Internet and Cold War-Style Propaganda in the Former Soviet Republic

– Anne VanderMey

Today's battle over media messaging has echoes of the Cold War. But modern disinformation in Russia also targets truth itself.

On a wintry Saturday in Berlin earlier this year, about 700 people staged a protest outside German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s office. They carried banners with messages like “Our children are in danger,” and “Hands off my child.”

They were there because they had seen the stories about a 13-year-old German-Russian girl raped by Syrian migrants, migrants whose right to enter the country Merkel had championed. Salacious reports on Russian news media stoked outrage in the German capital, claiming, among other things, that the girl was snatched from a train station and assaulted by several men, and that Germany was orchestrating a cover up.

By the time it was clear the story was fabricated (according to investigators’ findings and the girl’s later testimony), the news had already spread on social media — with one video of the girl’s aunt detailing the horrific claims garnering more than a million views on Facebook and international attention.

Despite Germany’s cries of “information war” and the countries’ freshly chilled relations, tales of wildly inaccurate reports from Russia are by now far from surprising. Particularly during Russia’s military campaigns in Syria and Ukraine, the country’s media efforts appear to have dramatically grown in scale and scope. Last year, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry warned a Senate subcommittee that Russia was “spending hugely on this vast propaganda machine.” He meant it: while estimates of the total spent on information dissemination are difficult to pin down, in 2012 the Heritage Foundation put the amount spent on international propaganda at $1.4 billion in 2010 alone. The annual spending on the Kremlin’s English Language news channel, RT, is about $300 million.

Recent years’ run-up in resources is often compared to the USSR’s propaganda during the Cold War, and indeed, there are echoes of the anti-foreign power messaging of earlier era.

Recent years’ run-up in resources is often compared to the USSR’s propaganda during the Cold War, and indeed, there are echoes of the anti-foreign power messaging of earlier era. But the channels—if not the contents—have radically changed. As Russia’s budget for messaging has escalated over the last decade and moved online, its ingenuity, technical savvy, and volume has grown, too.

Witness the Internet Research Agency, an organization whose workings were chronicled last year by The New York Times. On Sept. 11, 2014, dozens of Twitter accounts started reporting that a Columbia Chemical plant in Louisiana was on fire, and that it was spewing toxic waste. Twitter user @AnnRussela posted an image of a building surrounded by fire, @Ksarah12 even had a video. But once the journalists tagged in the tweets started looking into the explosion, it became apparent that not only was there no fire, the Columbia Chemical plant didn’t even exist.

The agency was estimated to employ hundreds, and possibly thousands of people to work 12-hour shifts to fabricate stories, write nationalistic comments on actual stories, and berate anyone publicly skeptical of Moscow leadership.

The accounts were actually run by a Russian organization referred to as the Internet Research Agency, an arrestingly sophisticated operation dedicated to spreading pro-Russian sentiment and misinformation online. The agency was estimated to employ hundreds, and possibly thousands of people to work 12-hour shifts to fabricate stories, write nationalistic comments on actual stories, and berate anyone publicly skeptical of Moscow leadership.

The targets of such campaigns and media reports are wide ranging, including journalists, the United States, Russian opposition leaders. Often, reports work to bolster the far left or right wings of Western politics. And taken together they amount to a sustained assault on the credibility of the Western narrative—and the idea of credibility itself. After all, if half the stories on the internet are fabricated, why believe anything you read there?

The tide of disinformation from the country has been so effective that it is often described as a central pillar of Russia’s political apparatus. Any cold war is a struggle for public opinion, but the contest has gained particular strategic importance in Russia in recent years, as the country’s military budget erodes with sinking oil prices. Both the European Union and NATO have set up offices specifically to track and combat false stories, many with links to Russia.

Yet however sophisticated the campaigns may be, the free flow of information on the internet is far from an unadulterated blessing for Russia’s media control efforts. While Russian messaging has adapted to the online world and then some, the unfettered availability of online information still poses serious challenges. The web has become a platform for dissidents, like Gary Kasparov with his prolific Twitter feed, or Alexey Navalny with his anti-corruption blog, as well as a portal to unfiltered stream of international information. While Russia has flooded Instagram, Twitter, and other sites with big money and flashy tech, much of the messaging there is far from innovative, and in the end may not be as effective in the long-term as its ubiquity might suggest.

While Russia has flooded Instagram, Twitter, and other sites with big money and flashy tech, much of the messaging there is far from innovative, and in the end may not be as effective in the long-term as its ubiquity might suggest.

To be sure, not all Russian media is subject to state control. But one need not look far for evidence of disinformation on a massive scale. A particularly instructive place to start is the country’s 2014 military campaign in Ukraine. As Russia invaded the country and held territory, Russian reports insisted that troops simply weren’t there. "I say every time: if you allege this so confidently, present the facts,” Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov prodded reporters in early 2015, after Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko told the World Economic Forum that Russia had 9,000 troops in the country.

Because of their official non-existence, Ukrainians referred to the soldiers who carried Russian weapons and wore unmarked Russian uniforms as “little green men.” It wasn’t until December of last year that President Vladimir Putin seemed to admit that there was, in fact, a military presence in the country.

The wholesale denial of a ground invasion is not, at its core, a terribly original idea—no matter how brazen. The strategy, as with much of Russia’s new media campaigns, has roots in the USSR. Writing in a brief for the Institute For The Study Of War, Russia observer Maria Snegovaya says that the country is deploying a Cold War throwback tactic in Ukraine called “reflexive control.” The concept is to “take advantage of pre-existing dispositions among its enemies to choose its preferred courses of action,” she writes. In this case, that means giving Western powers a plausible excuse to avoid intervening in Ukraine by denying Russia was invading in the first place.

In fact, despite its tech savvy, Snegovaya argues that Russia’s media arm lags in creativity. “The Kremlin’s information warfare generally, is not the result of any theoretical innovation,” she writes. “All of the underlying concepts and most of the techniques were developed by the Soviet Union decades ago.”

The continuity between USSR messaging and modern media is both a strength, with its time-tested effectiveness, as well as a weakness. But it is valuable to step back and take stock of what aspects of messaging in Russia is a retread from a Cold War toolbox, and what has changed about the country’s new media campaigns.

The continuity between USSR messaging and modern media is both a strength, with its time-tested effectiveness, as well as a weakness.

The similarities are significant. Today, there are four frequently cited basic pillars of Russian information campaigns: dismiss, distort, distract, and dismay — sometimes referred to as the four D’s. They haven’t changed much over the decades. Ben Nimmo, information defense fellow with the Atlantic Council's Digital Forensic Research Lab, writes that the strategy is “both repetitive and predictable” — albeit potent.

Here’s how the four D’s strategy manifest itself in Ukraine: First, dismiss. This happened most famously when Russian officials denied any military involvement in the country, despite mounting evidence suggesting otherwise. Second, distort. One Russian actress claimed that Ukrainian troops had crucified a child — a claim quickly debunked by Western media. Third, distract. Some Russian media outlets claimed that the famously disappeared Malaysian flight had been shot down by Ukraine.

Why bother with the outlandish claims? The chaos of mutually hurled accusations sows an environment of general doubt and distrust. Even if the accusation itself isn’t credible, credibility itself becomes scarce, leaving audiences unsure who, if anyone, to believe.

And then finally, there’s dismay. In the Russian media this can take the form of alarming posturing, and most darkly, references to Russia’s nuclear arsenal. During the Ukranian conflict, Kremlin-backed journalist Dimitry Kiselyov issued a stark warning over proposed U.S. sanctions. "Russia is the only country in the world that is realistically capable of turning the United States into radioactive ash," he said. While he spoke, B-roll video footage of an unfurling mushroom cloud following a nuclear blast played on a screen behind him.

A few key themes run deep through both Cold War-era messaging and in modern Kremlin backed media—mainly revolving around Russia's strength and Western corruption. Audiences can expect a familiar refrain, Lilia Shevtsova writes in her book Lonely Power: Why Russia Has Failed to Become the West and the West is Weary of Russia : “Americans cannot be trusted, Americans are guilty; Americans are hypocritical; and the Americans are a threat!”

But despite clear echoes from the past, there are large swathes of the Russian narrative that have changed in dramatic ways. Perhaps the most visible is the promotion of Putin as a virile, macho, online personality. Consider, for example, Putin’s Army. In 2011, a video called “Rip it for Putin” appeared on YouTube. In it, a woman identified as a student, wearing heels and a blazer, announced a contest in which women should upload video of themselves taking people to task in the name of the Russian leader. “Young smart and beautiful girls have formed an army of Putin,” the narrator says as the camera lingers suggestively. “An army that will rip anyone up for him.” By the end of the video, it seems almost natural when she rips open her tank top.

At first glance, “Rip it for Putin” seems uniquely bizarre, but it’s actually part of a sizable subgenre of modern Russian media. Putin’s Army, which is allegedly at least partially government-funded, has also created multiple videos of Russian women in bikinis washing cars for free in support of Putin — as long as they’re Russian cars. In 2002, two women singing the song “I Want a Man Like Putin,” became a surprise hit. And in one of the stranger instances, in 2011 a man who had recently shaken Putin’s hand was then permitted to touch 1,000 breasts with that hand, on camera.

The shift toward venerating the strongman aesthetic is recent. After the end of the Cold War, “there’s a focus on sexuality that comes flooding in in the 90s,” says Valerie Sperling, chair of the Department of Political Science at Clark University, and author of Sex, Politics, and Putin: Political Legitimacy in Russia. After Russia opened up to the rest of the world, it also saw a wave of Cosmopolitan-like magazines, American movies, and other trappings of sexual power.

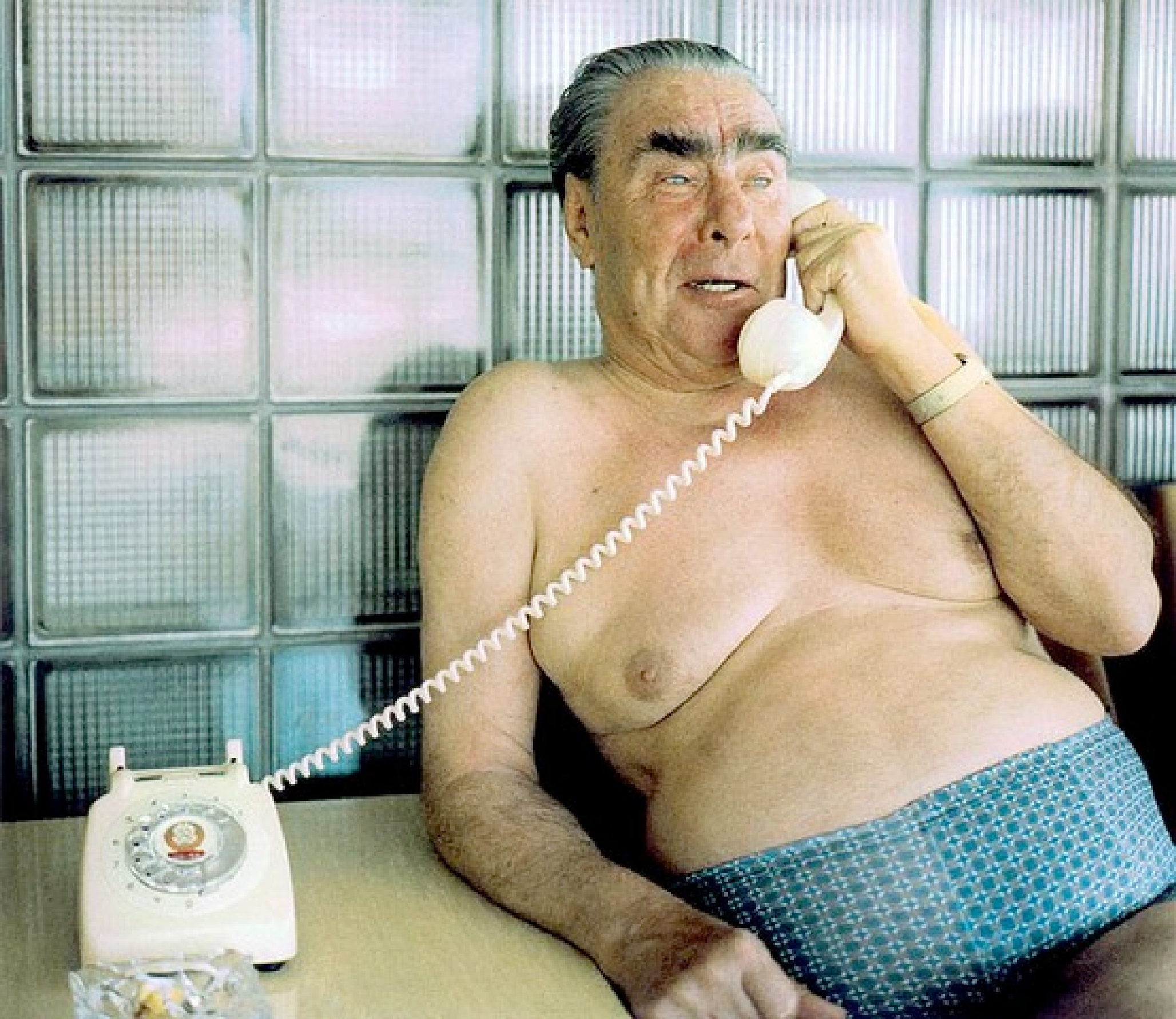

Contrast the modern image of Putin as a supremely masculine leader, with Leonid Brezhnev. A 1970s-era photograph of the Soviet leader using floaties in a swimming pool, with a bathing cap, is about as far as it is possible to get from Putin’s recent spate of photo-ops. In 2015, Putin scored eight goals while playing hockey with National Hockey League players. In 2013, he charted the murky depths in a James Bond-esque submarine. And in 2009, he fed a horse from his hand while shirtless. The list goes on.

The motivation behind Putin’s positioning may have roots in Russia’s somewhat tenuous modern geopolitical position. During the Cold War, the USSR was clearly one of the most important countries in the world. Gestures of machismo were mostly unnecessary. “The world was more binary,” Sperling says. “It was more obvious that there were two superpowers.”

Russia’s relatively diminished role in world events may also be playing out in other ways. Consider Soviet Union messaging and propaganda, which was preoccupied with painting the republic as a force for world peace. Posters from the era frequently pair the hammer and sickle with white winged doves. Contrast that with the modern imperative, which seems to be almost the opposite. “They’re communicating, ‘The west is not going to push us around, we’re going to do whatever want,’ ” Sperling says. For example, going toe-to-toe with Western powers in Ukraine and elsewhere may vex foreign countries, but elevates Russia’s status as a key player on the world stage.

But perhaps the most important difference between Soviet propaganda and messaging in the modern era: Russia today is less concerned with credibility.

But perhaps the most important difference between Soviet propaganda and messaging in the modern era: Russia today is less concerned with credibility. While the USSR went to great lengths to paint itself as a peaceful and legitimate world power, and bolster its international perception, Russian media is often undeterred should they be caught in a lie or be accused of bullying.

“Russians [no longer] aim to preserve the credibility of the Russian government’s narrative in Western eyes,” writes Jon White, associate professor of European politics at the London School of Economics in a paper for Vrije Universiteit Brussel’S Institute for European Studies. If “Russian disinformation can convince some westerners of the truth of Russian disinformational themes, so much the better, but Russia will settle for a more modest goal. They want to undermine the credibility of the media, especially the internet, as a medium itself.”

In that sense, troll armies, wild untruths, and state-controlled media may not need to be particularly innovative or compelling in order to serve the function of diluting the power of any online critiques of Moscow. “Russia’s new propaganda is not now about selling a particular worldview,” writes the Levada Center’s Alexei Levinson. “It is about trying to distort information flows and fuel nervousness among European audiences.”

Domestically, too, the tactics have the effect of polluting the conversation. "The paid trolls have made it impossible for the normal Internet user to separate truth from fiction,” says Kremlin critic Navalny. “The point is to spoil it, to create the atmosphere of hate, to make it so stinky that normal people won’t want to touch it.”

But that still leaves gaps where positive messaging should go. Levada Center chief Lev Gudkov says criticism has had an effect on public perception, even while presidential approval ratings remain high. “Corruption scandals are erupting weekly, with high-level officials appearing on the screen,” he recently said. “Whether one likes the regime or not, the general impression is one of total corruption.”

Abroad, too, there are chinks in the armor of Russia’s well-funded publicity machine. RT, formerly Russia Today, is the English-language network that has hired MSNBC’s Ed Schultz, and syndicates legendary anchor Larry King’s show, and has a relationship with King himself. While reliable viewership numbers are difficult to obtain, even the controversial statistics the network releases significantly lag other more established networks—and that was before several anchors publicly quit over what they said was misinformation about Ukraine.

"The paid trolls have made it impossible for the normal Internet user to separate truth from fiction,” says Kremlin critic Navalny. “The point is to spoil it, to create the atmosphere of hate, to make it so stinky that normal people won’t want to touch it.”

What’s an aging world power to do? One possibility is significant reform. Michael McFaul, former U.S. ambassador to Russia, said before he took the job that the best way for Russia to rehabilitate its image abroad, would be “not to arrest Garry Kasparov, and to allow Mikhail Kasyanov to participate in the presidential vote,” a sentiment that could be updated to include any of the various prominent current critics of the Kremlin as well.

As for domestic messaging, the country is already testing the limits of how heavily a modern society can rely on officially directed media to maintain order. Right now, most Russians get their news on the country’s heavily regulated TV stations, but internet usage is growing. The estimated share of people who are connected in the country is now more than 70%, up from a majority of people never going online in 2009, according to market research firm GfK. Recent web regulations signed by Putin met with fierce backlash this summer, which is to be expected given that 63% of Russians say a censor-free internet is important. Eight in 10 Russians ages 18 to 29 say the same.

Citing a century’s old worry from a French aristocrat, Navalny and others have recently pointed to a passage from a 1838 travelogue by French aristocrat Marquis de Custine, who said of Russia: “The political regime here would not survive 20 years of free communication with Western Europe." That warning has become increasingly urgent as the proliferation of modern media, however varied and untrustworthy it may be, mean the country may not have a choice in the matter.

* * *

Anne VanderMey is a reporter and editor whose writing about global business and finance has appeared in Fortune magazine, BusinessWeek, and various newspapers. She lives in Brooklyn.

Cover photo courtesy of Flickr/James Vaughan