Spring 2020

Hearts and Stomachs

– Scott McLemee

Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle has come to symbolize an era of muckraking and reform. But its author sought revolution, not regulation.

Upton Sinclair's The Jungle (1905) is a well-known novel that tells a seldom-remembered story. Decades of its usage in U.S. history classes might be to blame.

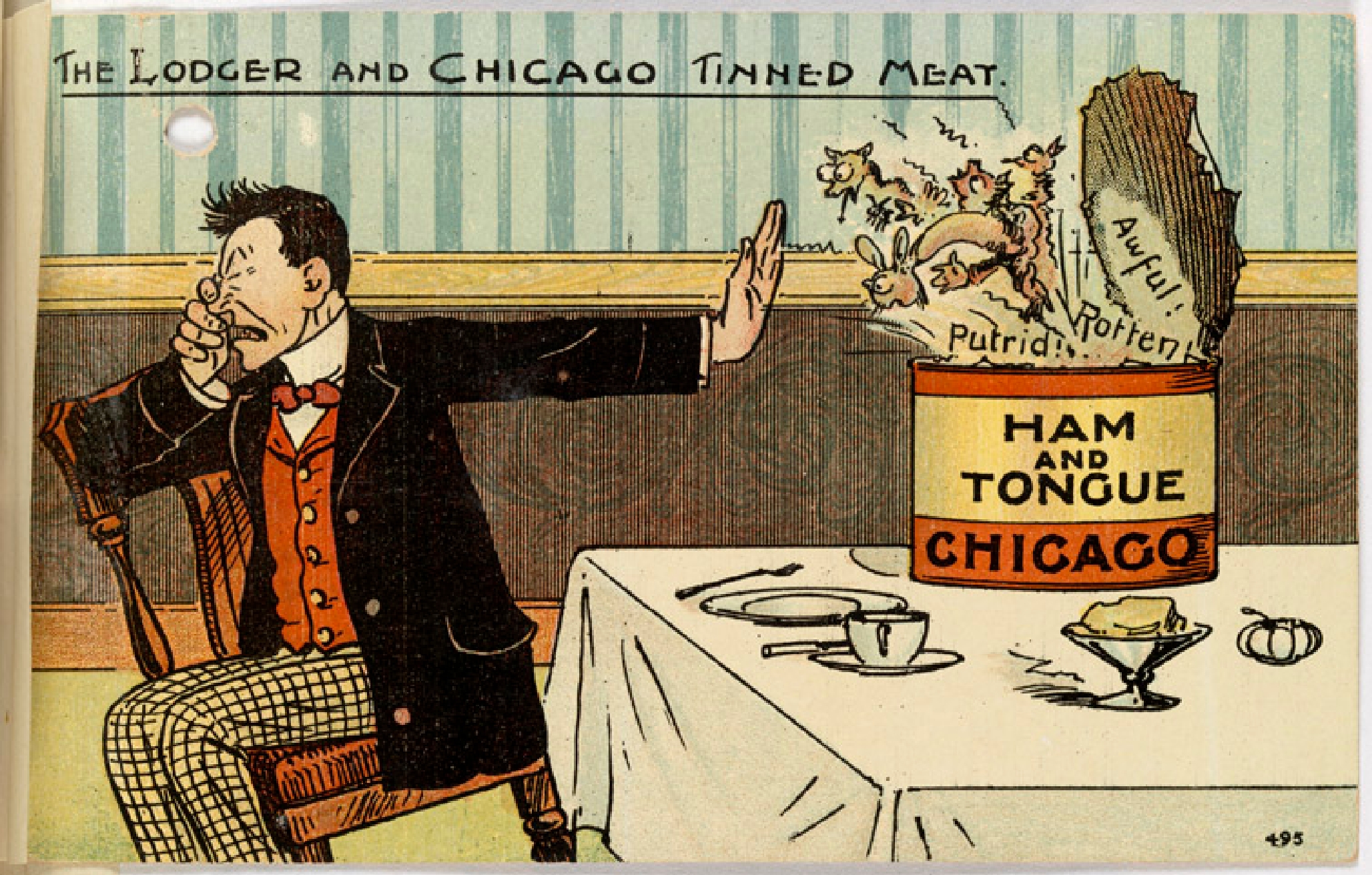

Set in Chicago’s tight-knit Lithuanian community at the start of the twentieth century, The Jungle’s central character, Jurgis Rudkus, is the archetypal immigrant worker, driving himself to the limits of endurance to support a family. But the novel’s few pages describing ghastly conditions in the city's meat-processing plants are the words that have burned themselves into the public mind – in a way that Rudkus and Sinclair's other characters never did.

These vivid descriptions of the meat industry created a certain narrative about the novel that has left its mark on the country's historical memory. The Jungle has become an important document in the rise of the regulatory state. As such, it also can be used to sum up the Progressive Era in a compelling and provocative way that is guaranteed to arrest the attention of even the rowdiest classroom with its gross-out details.

Yet while The Jungle's meta-narrative is neat and effective, the ingredients from which Sinclair created it merit closer inspection: The Gilded Age. The dawn of muckraking. An awakening to the possibilities of reform.

"I aimed at the public's heart," as Sinclair later put it, "and by accident I hit it in the stomach."

How did those ingredients combine into an accepted version of events? Amidst all the greed and corruption in the age of the robber barons, some of the worst excesses could be found in Chicago's stockyards and rendering plants. Upton Sinclair went undercover and revealed what went into the meat on America's plates. ("Went into" is divulged by the book in an appallingly literal sense.)

The expose created a sensation (primarily one of nausea) and The Jungle rapidly became an international best-seller. Among its readers was President Theodore Roosevelt, who was reported to have thrown his breakfast sausages out the window. That's the kind of publicity money can't buy.

Roosevelt sent investigators to Chicago who confirmed that the meatpacking industry's hygiene was troubling, at best. Public clamor led to sweeping reforms that included regular government inspection of the plants.

History’s narrative concludes by asserting that Sinclair's muckraking expose (conducted in 1904 and published the following year) was the major, and perhaps decisive, push to the enactment of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. As tales of social progress go, it is remarkable in its efficiency. And it comes complete with a happy ending: Thanks to investigative reporting and the advent of regulation, American consumers regained their appetites.

Prying into Packingtown

A certain percentage of Americans undoubtedly remained vegetarians. And important aspects of The Jungle and its context are lost in the civics-minded lesson recounted above.

But before considering them, it is worth recalling the nasty particulars of meat production that made such an impact on readers in 1905. It is one of those rare moments in history in which the physical sensations of an author and his public were almost certainly in sync with those of posterity.

The Jungle is set in a Chicago neighborhood then called Packingtown. As the newly hired immigrant workers are transported to the meat-processing plant, Sinclair depicts them as overwhelmed by odors well before they can see where they will be employed.

Cattle and hogs arrive continuously by train. They are unloaded, and, in time, fed into the machinery of slaughter. Though Redkus feels horror at the animals' suffering, he is awed by how smoothly the process functions. The carcasses are stored in dirty rooms, at whatever temperature comes with the season. Exhausted workers relieve themselves when and where they can, including on the floor. Those in the habit of spitting do so, and nobody can afford to miss a day of work just because of a wracking cough — any more than an animal would go unprocessed just because it was diseased, or had died in transport. Meat is not wasted just because of rot.

Rats get an early taste of the beef and pork in the plant, leaving hair and feces behind. When poisons do kill some of them, the dead rodents go through the same grinders as the ingredients intended for processing – including sawdust. That insects are involved at every stage of production probably goes without saying.

Sinclair said that he witnessed some of these factory conditions with his own eyes. He learned of others from interviewing workers. The exact proportion of The Jungle’s first- and second-hand information remains a matter for debate.

The degree to which Sinclair exercised authorial license by combining details from the very worst cases into a picture presented as typical of the whole industry is also at issue. He admitted that he was unable to document the book's most appalling claim: that workers sometimes fell into the vats where animal fat was melted into lard, and their bodies discovered only after prolonged cooking. "There had been several cases," Sinclair wrote in his autobiography, "but always the packers [i.e. owners of the plants] had seen to it that the widows were returned to the old country."

On the other hand, at the height of The Jungle's notoriety, Sinclair could shore up his credibility with "the court records of many pleas of guilty" by Chicago's meat magnates "entered in various states to the charge of selling adulterated meat products."

Inspiring an Army

Verisimilitude was only one element of the book’s impact. Nor did Sinclair have any glimmer of apprehension that it would make him an honorary godfather to the Food and Drug Administration. Too often The Jungle is treated as an affidavit regarding dead animals, rather than a novel about living humans.

"I aimed at the public's heart," as Sinclair later put it, "and by accident I hit it in the stomach." Yet this pithy and memorable comment understates his ambitions for the book, and his disappointment at its reception.

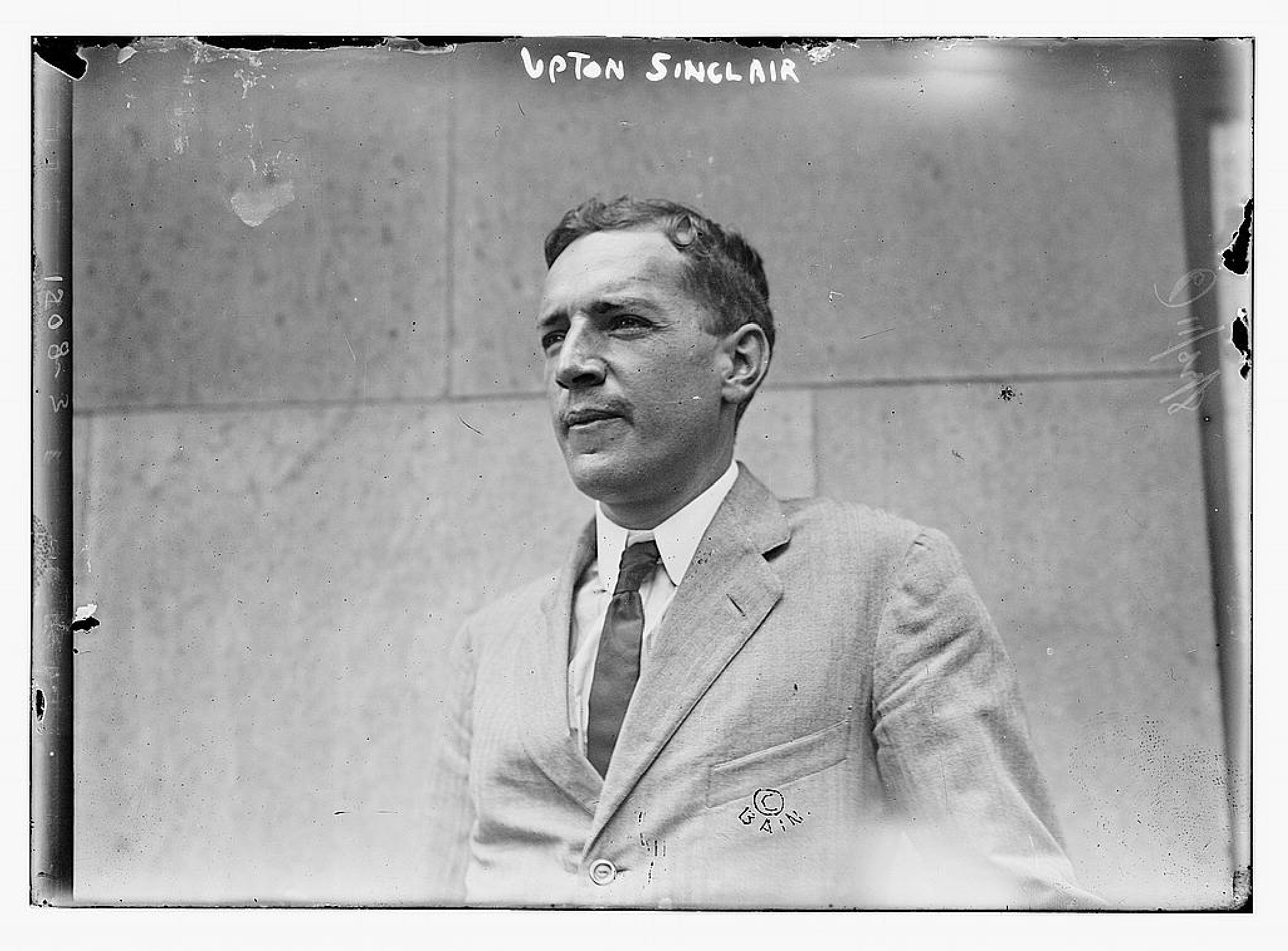

Sinclair was 26 years old when he wrote The Jungle but by no means an author at the beginning of his career. His upbringing had been irregular, but it proved to be remarkably suitable preparation for the role of socially-minded novelist.

Both of the author’s parents came from prosperous families, but his father's alcoholism generated extreme and frequent reversals of fortune. Sinclair's childhood consisted of moving back and forth between dire circumstances and being taken in by more stable relations. At the age of sixteen, he began cranking out thousands of words of fiction a day — what now might be called young-adult historical novels — which paid for his university education.

By his early twenties, Sinclair resolved to throw himself fully into the struggle to become a great writer: someone of the literary calibre of the artists his own adolescent hackwork had enabled him to study.

Sinclair’s first few serious novels were not well-received. The emotional strain upon him was incredible, to say nothing of the economic anxieties. (Both were compounded by the anxieties of fatherhood following an early and ultimately regrettable marriage.) It was during this agonizing period that he came into contact with a few socialist writers and thinkers. Their ideas resonated with his own experience of the extremes of wealth and poverty. They also allowed him to imagine a better future; a future to which his writings might contribute.

Sinclair took the next step in 1904 by joining the Socialist Party of America. He started to write for The Appeal to Reason, a Midwestern socialist newspaper. It had a quarter of a million subscribers and was still growing thanks to "the Appeal Army" – a loyal cohort of supporters which made sure the publication found new readers.

One of Sinclair's first contributions to the paper was an article about the unsuccessful strike in Chicago's stockyards that summer. His assessment hit just the right notes of anger and defiance, and it was well-received by the paper's readers, including workers in Packingtown. With an advance of five hundred dollars from the Appeal, Sinclair moved to Chicago for several weeks of research for what became The Jungle, which ran as a serial in the newspaper before appearing as a book.

By the turn of the century, five American meat-packing companies slaughtered eighty percent of the country's cattle.

After ten years of making a living by his pen (if just barely) Sinclair was, in a sense, already at mid-career. He published a novel on the Civil War – Manassas: A Novel of the War – shortly before heading to Packingtown. He considered it an artistic triumph. Some reviewers agreed — but its sales were so discouraging that he abandoned the plan of making it the first volume in a trilogy.

It was fellow socialist author Jack London who showed a clear grasp of Sinclair's aspirations when he called The Jungle "the Uncle Tom's Cabin of wage slavery." The novel opens with Redkus at his wedding party, embedded in a warm and vividly depicted community. The subsequent series of dehumanizing experiences in Packingtown reduces the protagonist to an isolated and desperate individual who is at last reborn within a political movement for a "Cooperative Commonwealth" of democracy and equality.

It is this narrative of The Jungle that is closest to Sinclair’s intentions. It is the work of an author possessed of the hope that life will imitate his art.

Regulations and Restlessness

The Jungle’s cumulative aesthetic impact derives from Sinclair's attempt to generate sympathy (heart), disgust (stomach), and ideological fervor (head). In 1905, the combination was volatile. By 1912, membership in the Socialist Party was six times what it had been when Sinclair joined it. Only part of this growth can be attributed to The Jungle: The party's presidential candidate, Eugene Debs, was both charismatic and a uniquely gifted public speaker. All those Appeal Army volunteers surely played their part.

Indeed, the novel's immediate influence and its lasting reputation have relatively little to do with its effectiveness in spreading the gospel of proletarian revolution. Many a reader over the years has grown restless with the book’s final chapters. Redkus himself all but disappears. The narrative peters out. New characters enter, discoursing at length on the origins, goals, and methods of the socialist movement.

In The Industrial Republic (1907) — a nonfiction work written as The Jungle was at the peak of its success — Sinclair was confident that the United States was on the verge of a radical transformation. He assured readers that the Cooperative Commonwealth could be established within about a year of the 1912 presidential election. His passion, however unmistakable, clearly did not prove contagious.

High-school American history usually identifies a key role for The Jungle in inspiring regulations to bring the noxious aspects of capitalism (its hog-eat-hog phase, if you will) under control. But the author himself knew better than this.

Individual states had been trying to protect their citizens from unhealthy and dishonestly advertised foodstuffs for decades before Sinclair moved to Packingtown. Calls for federal inspection of meat began no later than the 1880s, when European countries began to ban U.S. beef and pork because of contamination. (Meat imported from Argentina proved safer.)

The first federal meat inspection laws were passed in the 1890s, with the support of the same major packing houses that dominated the Chicago portrayed in the novel. Indeed, these companies urged stricter enforcement — not to protect customers but to reduce competition by driving smaller producers out of the business. By the turn of the century, five American meat-packing companies slaughtered eighty percent of the country's cattle.

It was fellow socialist author Jack London who showed a clear grasp of Sinclair's aspirations when he called The Jungle "the Uncle Tom's Cabin of wage slavery."

Federal inspection was "maintained and paid for by the people of the United States," Sinclair wrote in 1906, "for the benefit of the packers. … [M]en wearing the blue uniforms and brass buttons of the United States service are employed for the purpose of certifying to the nations of the civilized world that all the diseased and tainted meat which happens to come into existence in the United States is carefully sorted out and consumed by the American people."

Only much later did economists develop the concept implied by Sinclair's remarks: "regulatory capture," the strong and perhaps ineluctable tendency of an industry (especially a concentrated one) to gain sway over the policies and agencies meant to hold it accountable.

In the present day, the Federal Meat Inspection Act of 1907 seems to have been written with The Jungle in mind. Its provisions included continuous inspection of stock animals while alive, and examination of their carcasses before being processed. The aftermath of this seemingly decisive set of regulations has been a cycle of periodic revelations about dangerous, unsanitary conditions, followed by calls for improved inspection.

Sinclair did not rest on his accomplishments. It perhaps bears mentioning that his literary career continued for another sixty years, with probably as many books. He also ran a campaign for governor of California in 1934 to hold another President Roosevelt's feet to the fire, prodding FDR from the left to more expansive goals for the New Deal.

As for The Jungle, Sinclair’s later judgment of its impact was sharp and precise. "I am supposed to have helped clean up the yards and improve the country's meat supply," he wrote in 1932 in American Outpost: A Book of Reminiscences, "though this is mostly delusion. But nobody even pretend that I improved the conditions of the stockyard workers."

Scott McLemee writes "Intellectual Affairs," a column on books and ideas at Inside Higher Ed.

Cover Photograph: Government inspectors examine carcasses at a meatpacking establishment in Omaha, Nebraska, 1910. (U.S. National Archives)