How Democrats and Republicans (Mostly) Flipped on Education

– Shannon Mizzi

Reagan wanted to dismantle the Department of Education. Bush passed “No Child Left Behind.” Obama has taken a relatively-hands-off approach. What gives?

Over the last 30 years, an extraordinary political reversal on education policy has occurred. In sharp contrast to Ronald Reagan’s call to “dismantle” the Department of Education, Republican President George W. Bush’s administration advocated higher levels of federal spending and involvement in education through “No Child Left Behind.” Likewise, in a departure from longstanding Democratic Party dogma, President Barack Obama has led a relatively hands-off approach to education by the federal government (save for his “Race to the Top” initiative). Curiously, this switch has taken place despite the fact that new policies advocated by each party have the potential to alienate significant components of their electoral bases, such as teachers unions for Democrats and small-government libertarians for Republicans.

How has such a reversal been possible in such a polarized political climate? In a recent article in Perspectives on Politics, Christina Wolbrecht and Michael T. Hartney argue that such vast policy shifts aren’t as unusual as they may initially seem. In fact, they can be contextualized within a broader political pattern in American politics that can be traced back to the post-war period. They highlight “the central role of issue definition” and the fact that, more than anything else, the terms in which issues are defined are key to the process of policy-making. Issue definition determines which policy alternatives are considered and presented to the public, and once a policy path has been chosen and implemented, it becomes very difficult to change the terms in which an issue is thought about.

Wolbrecht and Hartney found that seven major themes have characterized national discussions of education in the United States since 1948: federal funding, racial inequality, minority groups, discipline and morality (encompassing things like school prayer and the nature of civic education), school choice, standards and accountability, and teacher quality. The fact that these issues have never been equally emphasized (at least simultaneously) helps to account for party see-sawing; it is the intermittent redefinition of the issue that has changed the scope of policy options surrounding education.

But how and why was the education issue redefined? The Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling that state-enforced segregation of schools was unconstitutional ensured that racial inequality would dominate the national conversation for the next two decades. “At the same time,” Wolbrecht and Hartney explain, “ the strained resources of schools as the Baby Boomers reached school age, the launching of Sputnik, and heightened attention to class inequality contributed to defining education in terms of the need for funding.” Liberal social movements of the 1960s and 1970s led to the reactionary rise of the Religious Right in the late 1970s and early 1980s; “the resulting ‘culture war’ permeated the politics of education. Education problems were increasingly defined in terms of values and discipline,” write Wolbrecht and Hartney. Attention was repeatedly drawn to the growing achievement gap between American students and students in other countries, as well as the variable quality of education between American states. This led to a new focus on accountability for student performance, often through standardized testing.

Historically, when education was associated with resources and inequality, Democrats were more vocal advocates of education reform. When education became associated with values, it was Republicans who were more active in pushing for change. Now that education is associated with testing and achievement, the parties have pulled closer together.

This shift from thinking about education in terms of racial inequality to thinking about it in terms of standardized achievement and curriculum building shaped ideas about what actions the federal government could conceivably take to reform education. Since the 1990s, the focus has been on comparative national and international achievement levels, and we have seen a change from deep partisan polarization in the 1980s to a significant level of agreement in the 2000s, despite rhetoric to the contrary.

Historically, when education was associated with resources and inequality, Democrats were more vocal advocates of education reform. When education became associated with values, it was Republicans who were more active in pushing for change. Now that education is associated with achievement, the parties have pulled closer together. This new ideological closeness on education reform has allowed for the implementation of policies that run counter to traditional party positions.

Despite the significant overlap between the two parties, there are deep divisions within them. For Democrats, teachers unions, civil rights organizations, and minority voters have typically been party strongholds. This was especially true in the 1950s and 1960s when equality and federal funding were the salient issues. However, when resources and inequality were superseded in the public mind by student achievement and values, the position of teachers unions within the debate changed significantly. “[For Democrats] the shift in the definition toward excellence [meant that] they increasingly backed standards and accountability and teacher quality reforms over the opposition of teachers unions.”The fact that Democrats have continued to focus on standards and accountability shows that how an issue is defined in the public mind is often more important than how individual interest groups would prefer to define the issue.

Republicans, on the other hand, have historically relied on social conservatives and supporters of small government as influential members of their electoral base. The former have encouraged government involvement on issues like school prayer and school choice, but typically oppose the establishment of a common curriculum, while the latter tend to oppose federal interference in education because of its potential to expand the size and reach of the federal government. “Republicans have chosen to advocate for a bundle of policies that offer something for every stake-holding member of their coalition: school choice and value policies for social conservatives, and standards, accountability and teacher quality reforms for business interests.”

Wolbrecht and Hartney’s research suggests that party leaders do not consciously shape party positions, but instead react to changes in public conceptions of issues. This theory is not confined to education, and can be applied to most social and political issues debated today. By contextualizing policy shifts, we can better understand the political times we live in and perhaps look at issue definition more objectively, creating room for a greater number of policy solutions.

* * *

The Source: “'Ideas About Interests': Explaining the Changing Partisan Politics of Education” Christina Wolbrecht and Michael T. Hartney, Perspectives on Politics, September 2014.

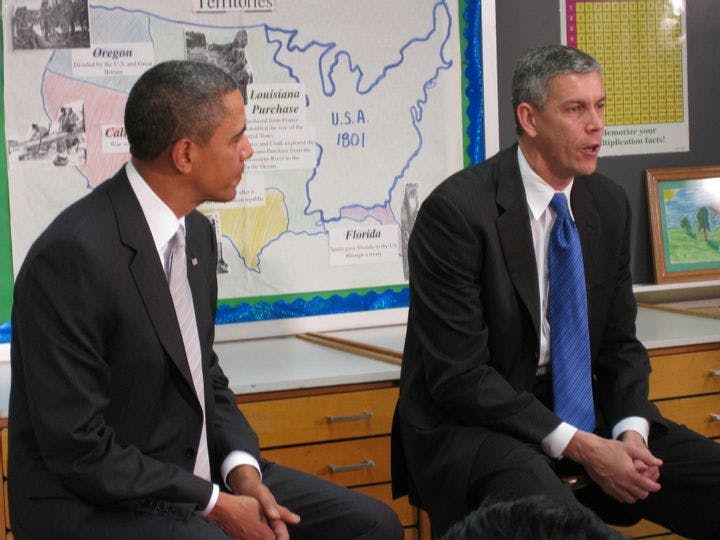

Photo courtesy of Talk Radio News