How the thrift shop, once widely denounced, became popular in America

– Caitlin Moniz and Zack Stanton

Up until the 20th century, thrift stores were denounced. When that changed, so did the charitable world — dramatically.

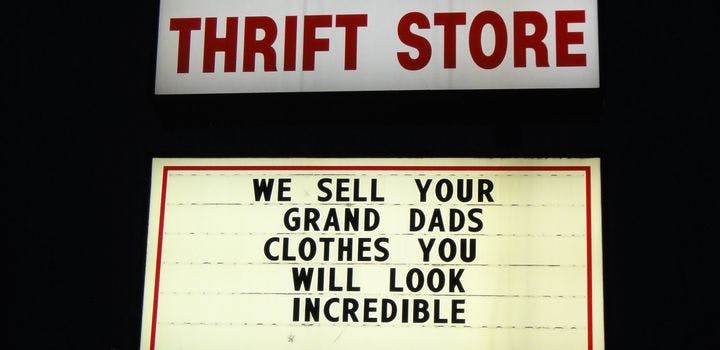

The thrift store has enjoyed something of a new life as of late, birthing chart-topping pop songs and becoming the shopping destination of choice for hipsters looking for vintage wares that are “authentic.” Of course, such stores, often run by Goodwill or the Salvation Army, serve a non-trendy role, too, as a shopping destination of necessity for America’s working class. It was not always thus.

“As early as the colonial era, writers, politicians, and other vocal critics denounced the sale of used goods,” writes Jennifer Le Zotte in New England Quarterly. Partly, it was born of a vague sense that such goods were sullied or unwholesome, but, writes Le Zotte, some of the opposition can be traced to anti-semitism (in this case, directed at Jewish-owned pawn shops).

One such illustration comes from “The Blue Silk,” a short story in the May 1884 Saturday Evening Post, in which the protagonist, Louisa, buys a pre-owned dress from the “Jewess behind the counter” of a resale store. When she wears it to a party, not only is she is socially ostracized for wearing the old dress of another girl, but she comes down with small-pox because of contamination from the resale store. The story neatly combined earnest bigotry with worries of the moral and physical dangers thought to accompany secondhand clothing.

What changed for secondhand goods? How did the American thrift store get repurposed? By a confluence of Christianity, capitalist philanthropists, and a rapidly changing early-20th century America.

The secondhand business model was co-opted by Christian charities, which anti-Semitic Americans saw as more suitable and wholesome than Jewish secondhand shops. In 1902, Reverend Edgar J. Helms founded what would later be known as Goodwill Industries, which employed the poor and disabled in gathering old goods for reuse. Located in New England, Helms sought to “take wasted things donated by the public and employ wasted men and women to bring both things and persons back to usefulness and well-being.” As Goodwill Industries declared with its new motto in 1922, it was “not charity, but a chance.”

“At the same time,” writes Le Zotte, “as urban populations swelled, the size of residential living quarters shrank, as did the areas where unused goods might be stored.” Industrialization produced a more frequent turnover of household goods. These factors were accompanied by a boom in immigration, and an increased demand for secondhand goods by these new Americans, for whom it served as a means of assimilation.

The early 20th century was also a transition period for the ideals of giving. Philanthropists, often prominent capitalists, were interested in new theories of poverty that could reshape their approach to charity; thrift was not so much a Christian virtue as an economic one. Philanthropy, writes Le Zotte, was instrumental in “distanc[ing] secondhand exchange from its negative associations while simultaneously affiliating it with benevolence.”

Similarly, circumstances during the Great War “required a ‘culture of giving’ in which middle- and working-class citizens would routinely respond to public appeals,” says Le Zotte. The convergence of philanthropy and capitalism created a viable secondary market for household goods. Once people saw opportunity, secondhand stores became part of the market, as well as a piece of the larger social effort to alleviate poverty.

Beyond the millions of secondhand goods given new life with new owners, the result of the rise of the thrift shop has been “unprecedented profitability” for Christian community organizations, says Le Zotte. Perhaps more transformational, though — and certainly more controversial — is the impact such stores have had on humanitarianism: the thrift store, more than any other analogue, “linked charity to capitalism decades before the ‘nonprofit sector’ had been so designated.”

The Source: “Not Charity, but a Chance”: Philanthropic Capitalism and the Rise of American Thrift Stores, 1894-1930” by Jennifer Le Zotte, New England Quarterly, June 2013.

Photo courtesy of Flickr/v-neck