Immigrants to Europe find an ally: Christian groups

– Miriam Kelberg

While Europe’s hot-button issue is the arrival of Muslim immigrants, Christian interest groups happen to be among their biggest advocates.

The rhetoric in Europe’s ongoing immigration debate paints a grim picture of non-European Muslims. They move into Europe, critics charge, and in their refusal to assimilate, reject liberal values and politicize Islam.

Despite the Islam-centric tone of Europe’s immigration debate, migrants to Europe are more likely to be Christian than Muslim. Including immigration between European countries, Christians comprise 56 percent of the European Union’s foreign-born population, while Muslims make up 27 percent. Even when excluding European-born immigrants, Christian immigrants still outnumber their Muslim counterparts by roughly one million residents.

The voices in the European immigration debate are numerous and far reaching. In the February 2015 issue of the Journal of European Public Policy, François Foret and Julia Mourão Permoser note that faith-based organizations — most of them Christian —still wield considerable power in the continent’s policymaking.

Religious politics have a strong tradition in Europe. Take Angela Merkel, the chancellor of Germany: she’s perhaps the most powerful European head-of-state, and her political party is Germany’s dominant Christian Democratic Union.

Differing from its member states, the EU itself has historically avoided aligning with any religion. (Most notably, a reference to the Christian heritage of Europe was edited out of the preamble of the former European constitution.) If a religious organization wants to have any political influence in the EU, Foret and Permoser observe, they must craft their arguments under a secular disguise, portraying themselves as experts on a given issue.Faith organizations do this through developing immigration know-how on the ground.

A representative of Pax Christi International describes what this looks like:

“To start from the level of the people we are working with means … to listen to their stories and to learn from them.... It is this act of humility that allows us to advocate from the perspective of victims and the poor, the only perspective that makes our work credible in the eyes of those we want to influence.”

That expertise goes a long way, and the human network that comes along with such outreach and field work gives faith-based groups the organizational infrastructure to persuade a government into action.

Partnering with secular groups, Christian organizations pressured FRONTEX, the agency for European border management, to host an advisory forum on immigration rights. After a prominent advocacy effort, the forum was created, with the Jesuit Refugee Service serving as the co-chair. Not only did Christian-aligned groups get a seat at the table, they sat at the head of it.

Despite the EU’s secularism — or perhaps because of it — Christian groups have found new relevance on pressing issues.

These groups own a symbolic credibility merely because of their Christian roots — a credibility that is not extended to other faith-based organizations, most notably those that are Muslim. As Foret and Permoser explain, “The main Catholic and Protestant organizations benefit from the fact that they are linked to the ancient majority churches whose positions are taken for granted.” Since Christian values developed alongside much of European culture, their presence is so comfortable that, with new secular language, they are not seen as religious so much as just a natural part of the European landscape.

Even while Muslim communities are active in local and national issues, their presence is marginal at the supranational level. In the EU, Foret and Permoser say that despite a secular face, “religion still works as a cultural marker enabling traditional (mostly Christian) players to have a greater legitimacy in European deliberations than those perceived as newcomers.”

And yet, they use this legitimacy to embrace immigrants, many of whom are themselves Muslim. Christian organizations, write Foret and Permoser, see “lobbying for a more liberal migration policy as a tool … to achieve their real objective, which is to protect the dignity of the person — a concept strongly anchored in Christian theology.”

Immigration policy determines who can claim particular identities. It declares who is welcomed and who is excluded; who can access certain rights and who cannot. And as religion defines “the symbolic boundaries of belonging to the political community,” it is paramount in the ongoing immigration debate.

While Europe’s hot-button issue is Muslim immigrants, Christian interest groups happen to be among their biggest advocates. As one interviewee tells Foret and Permoser, all human beings are “citizens in the household of God.”

* * *

Further reading:

François Foret and Julia Mourão Permoser, “Between faith, expertise and advocacy: the role of religion in European Union policy-making on immigration,” Journal of European Public Policy (2015): 1-20.

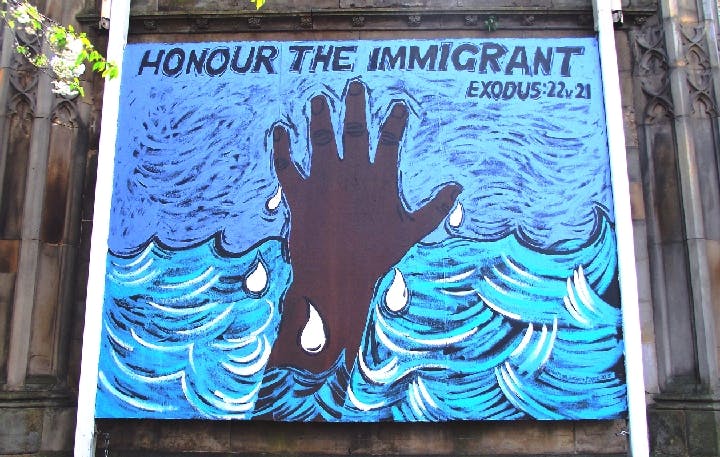

Photo courtesy of Flickr/byronv2