Learning to Say Goodbye to My Father: The Ritual of Letting Go

– Shihoko Goto

Sleeping next to a corpse, even that of a loved one, was a ritual I had long been dreading. Instead of bringing closure, it seemed a particularly cruel and gothic way to bring even more sorrow to a grieving family.

Sleeping next to a corpse, even that of a loved one, was a ritual I had long been dreading. Instead of bringing closure, it seemed a particularly cruel and gothic way to bring even more sorrow to a grieving family.

Yet Buddhist tradition in Japan dictates that a body lies in rest at home with the family for several days until a monk prays for the deceased's spirit to depart safely for its next life at the funeral, after which the body is cremated. And so my father’s body was brought back to my parents’ house in suburban Tokyo, the site which had been bought by my grandfather nearly a half-century earlier, and to which I had flown back to from Washington.

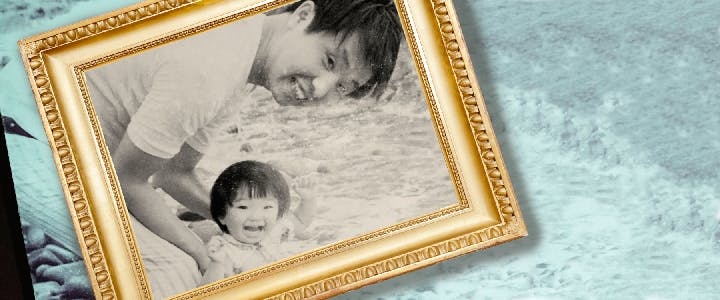

Having been in a steady decline from a debilitating lung disease until he was no longer able to breathe even for a minute without an oxygen tank, my father's last several months had been especially painful to watch. Given his struggle just to stay alive, his death was not unexpected, and in some ways, it was a relief that he no longer had to fight as he slowly ceased being the brilliant investment banker that he once was.

But I had failed to be there when he took his final breath. While I managed to fly in to Japan to see him every few weeks at his hospital bed since late last year, it just wasn’t enough.

But I had failed to be there when he took his final breath. While I managed to fly in to Japan to see him every few weeks at his hospital bed since late last year, it just wasn’t enough. Just when I was about to board the plane from Dulles on standby on May 8 after my mother called that the end should be coming soon, she called again to say it was all over.

Long haul flights are never for the faint of heart, but that flight was the loneliest journey I had ever taken. Having no one to talk to about my loss just minutes earlier, I had over 12 hours to myself to replay my final visit with my father the previous month, and to grapple with the guilt for not being there when it really mattered, in his final hours.

When I finally arrived at my parents' house, my father was laid out in a white futon on the tatami floor wearing a pure white kimono, a dagger placed upon his chest to ward off evil spirits. A long white candle burned and incense was lit, but the smell of lilies overpowered everything else.

It was the least likely setting my father would have been comfortable in, yet his face was calmer than it had been in a long time. In fact, he not only looked more serene, but he actually looked slightly more youthful than he had when I had last seen him in hospital six weeks earlier.

And without worrying about his oxygen supply, and not panicking every time he coughed, I was finally able to focus on who he really was, and what he meant to me, rather than seeing him as the sickly, frail patient.

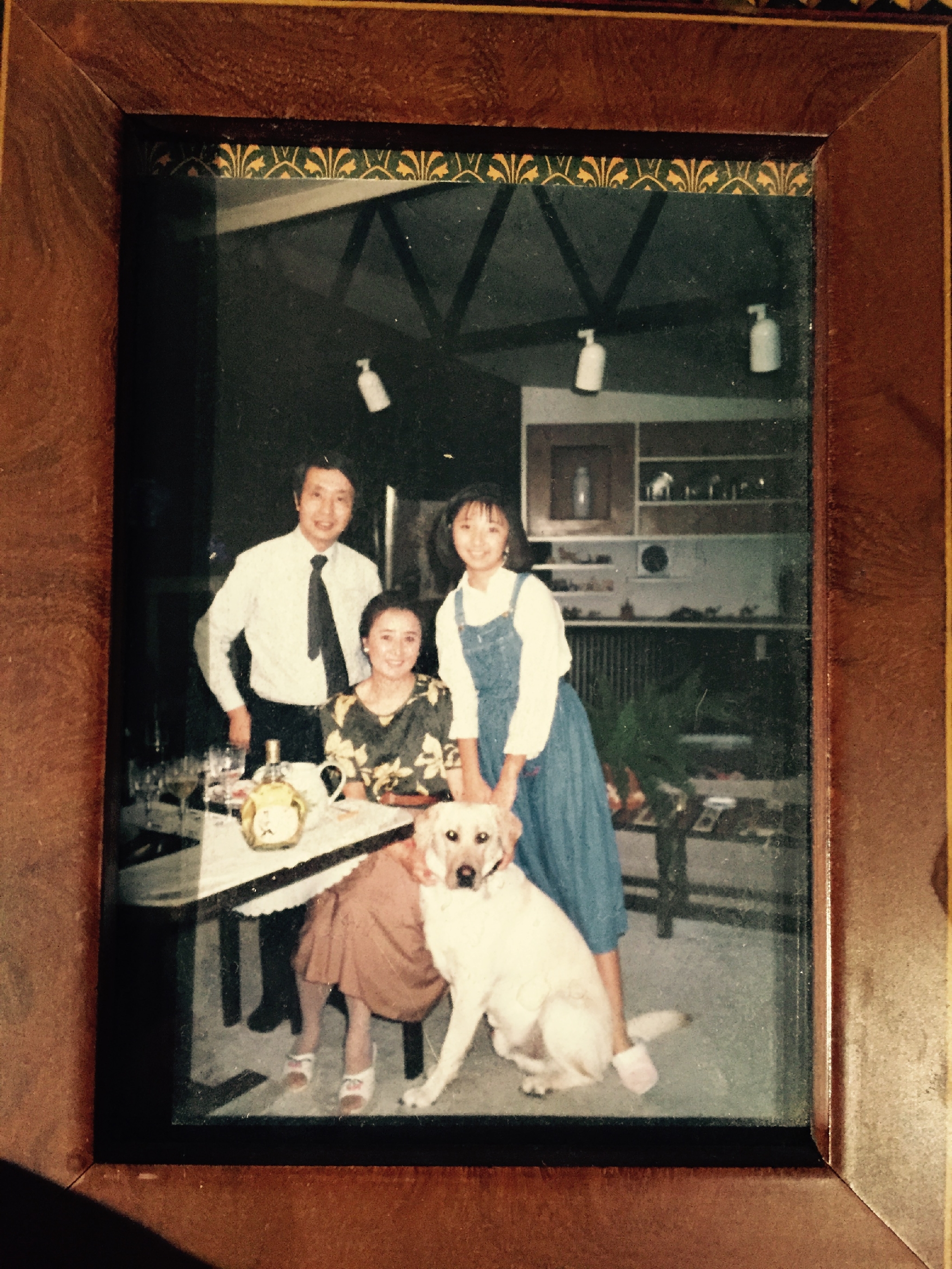

Born two years before Japan surrendered to the United States, my father Shigenobu was born to a well-to-do family of landowners in Saitama, which back then "might as well have been rural Vietnam," according to him. His thirst for knowledge of the wider world, and his drive to learn English in his teens in particular were key for him to pursue a career in international finance, which allowed my mother and me to spend several years in Los Angeles and Brussels. His passion and life decisions, in short, ultimately came to define my own life, and eventually, my children’s as well.

His passion and life decisions, in short, ultimately came to define my own life, and eventually, my children’s as well.

As relatives, friends, and former colleagues came over to pay their respects during the day as final arrangements for the funeral were made, I was able to spend time with my father each night, simply sharing time with him and talking to him about what had been, what could have been. It wasn’t a dead body that I was with. It was my father that I have always loved, who was sensible, proud, and always unafraid to be a bit irreverent, and who was also no longer suffering. This was the father that I wanted to remember, and when the time came for the undertaker to carry his body away to the temple, the pain of separation was overwhelming.

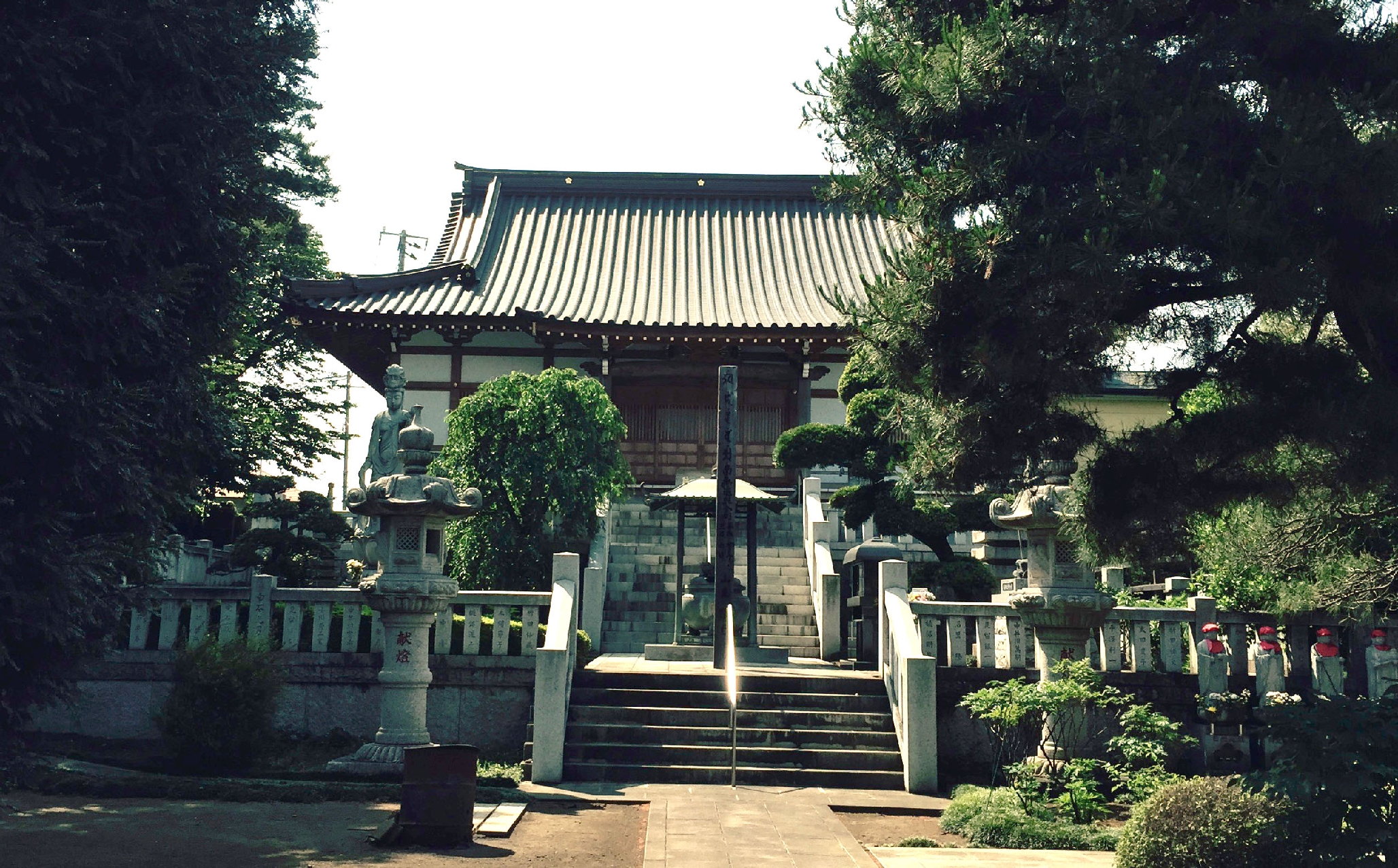

My father's body was cremated after the funeral, and his ashes now rest at my parent's house, in accordance to Buddhist tradition. His remains will finally be buried by our local temple on the 49th day of his death, a week after Father's Day.

***

Shihoko Goto is the senior Northeast Asia associate at the Woodrow Wilson Center's Asia Program.