Spring 2011

New to the Neighborhood

– Sarah L. Courteau

How can you be an urban pioneer when you move to an inner-city neighborhood where families have lived for generations?

A year ago I moved into a row house in northeast Washington, D.C., two miles from the Capitol. I paid $85,000, a price so low it’s a punch line in a city where the average home sells for more than $600,000. The hot water heater was missing, and the bathroom tub drained into a downstairs closet. My house inspector, a dead ringer for the gravel-voiced actor Sam Elliott, tramped silently from room to room, occasionally pausing to pronounce, “It’s not proper.” The house was in foreclosure and had been vacant for a couple of years, so when I found crayons under the old carpet, I was spared the guilt of imagining them in still-young fingers. But once, someone had loved this place. The backyard bloomed with rosebushes staked with weathered shoelaces. With an FHA-backed loan and a savvy contractor, I gutted the house and renovated it. I found myself realizing a dream I’d assumed was miles out of reach: I was a homeowner.

A white, single professional in my thirties, I moved into a neighborhood of modest houses that is almost 90 percent black and where about a third of the population lives below the poverty line. I’m a gentrifier, a category of urban resident that has become a lightning rod for debates about the evolution of our cities. Last year, a study published in the Journal of Urban Economics found evidence of gentrification during the 1990s in the majority of the country’s 72 largest metropolitan areas. But few places match the galloping pace of gentrification in the nation’s capital. In the last 10 years, Washington’s population has grown by five percent, after steadily shrinking since 1950. The white population is up by nearly a third. Since the 1960s blacks have been a majority in the District of Columbia, but that balance will likely shift in the next few years.

Unlike places such as Harlem in New York City, where yuppies have snapped up decrepit but once-grand brownstones, my neighborhood, which was originally settled by European immigrants, has always been working class. My two-bedroom is less than 800 square feet, upstairs and down, and lacks a basement. I love the neighborhood—known as Rosedale, after the recreation center on the next block—and feel proud and a little defiant to have pulled off a financial coup that’s landed me a comfortable life in a place that some relatives and friends, and, especially, taxi drivers (who collectively form a modern Greek chorus of prophetic doom) describe as “sketchy.” But it’s with a mixture of pride and embarrassment that I hear myself called an urban pioneer. Because, of course, this is a long-settled neighborhood. It’s only new to me.

Many of my neighbors have lived in Rosedale for decades, and others can trace their roots back generations. They remember when the neighborhood was a mix of blacks and whites, before whites began to pick up and leave in the middle of the last century. They remember when blacks did their shopping on H Street because they weren't welcome in downtown department stores. They remember when the Rosedale playground was desegregated, largely due to the efforts of local resident Walter Lucas, who one day in 1952 led a group of black children over to play and was beaten and then arrested along with one of his assailants. They remember the riots that tore the area apart for three days after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968 and left the area’s commercial spine, H Street, in smoking ruins. Fifty-year-old Stephon Starke recalls that word went out that businesses would be spared only if they displayed a picture of King in the window. His father had put a picture in the window of their house, but not at the liquor store he owned off H Street. Two Great Danes kept the store safe, but many other black-owned businesses did not survive.

H Street was in decline even before the riots. Afterward, though some businesses reopened, many damaged buildings remained vacant. The street was a mute reminder of social failure. Still, life went on. There were summer go-go concerts and afternoons at the Rosedale pool. Kids played in the streets under the watchful eyes of all the adults in the neighborhood. The 1970s saw the beginnings of the drug and crime epidemics that would become full-blown in the 80s. People started referring to parts of the neighborhood as “Vietnam,” and residents installed bars on their windows and locked doors they’d once left unlatched. In 1980, James Hill, the proprietor of Hill’s Market, where people sent their kids never worrying that they’d be shortchanged and old folks could buy food on credit, was shot to death in an argument over change for a newspaper and a pack of cigarettes.

After the riots, recalls 45-year-old Necothia Bowens, who lives in a house on E Street N.E. that her great-grandparents occupied, the area was abandoned by city authorities. Their attitude, she says, was, “Well, you did this. It’s your mess to clean up.” No longer. In 2004, the D.C. government approved a major redevelopment plan calling for more than $300 million in (mostly private) investment in the mile-long commercial corridor of H Street that runs from Second Street N.E. to the Maryland Avenue intersection, three blocks from my house.

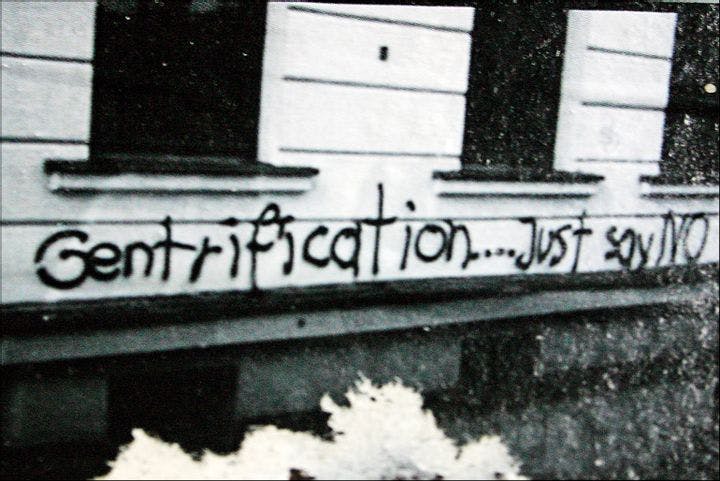

Today, H Street is an obstacle course of bulldozers and construction signs. An extensive streetscape project is under way, and track is being laid for a streetcar system that next year will connect this once-deteriorated artery to the Union Station transportation hub. Most evenings, young white partiers from other parts of the city and the Maryland and Virginia suburbs crowd into a string of new bars. During the day, foot traffic is sparser, and many of the faces are black. Muggings and break-ins do occur, but at about the same rate as in other parts of the city. A Rosedale gang known as the E Street Bangers is reportedly still active, though the only evidence I've seen of it is in graffiti. Serious violent crime is rare, and bar-goers and new residents are seldom targets. Long-abandoned buildings ring with the sound of pounding hammers, and a luxury apartment complex is rising on a vacant lot where a Sears once stood.

Though the word has only been in circulation for a few decades, gentrification has become another of the litmus test issues that define who we are on the political and—in the eyes of some—moral spectrum.

The very origin of the word “gentrification” to describe the process by which an urban area is rendered middle class is not neutral. The eminent sociologist Ruth Glass is credited with coining it in 1964 to decry the changes in working-class London neighborhoods. Though the word has only been in circulation for a few decades, gentrification has become another of the litmus test issues that define who we are on the political and—in the eyes of some—moral spectrum.

The lines of conflict are readily apparent in the comments readers leave on blogs that cover Washington’s transitional neighborhoods. Some writers are angry that the neighborhood is changing at all; others are angry that it isn't changing fast enough. Some want to control the change, ensuring that a curated mix of businesses is established—no chain stores, please, but nothing too “ghetto,” either. And some want to curate the people. Gentrification, though driven by economic change, often boils down to issues of race, even among diversity-celebrating gentrifiers. Elise Bernard, a 32-year-old lawyer who bought a house off H Street in 2003, has for years written intelligently and reliably about the area on her blog Frozen Tropics. Bernard, who is white, recalls a conversation she had with a college friend when she was contemplating renting out a couple of rooms in her house. “She wanted me to somehow racially balance the house, like bring in an African American and an Asian, and I’m like, ‘This is not The Real World. This is my house.’ ”

When I started reading Frozen Tropics, I was taken aback by the racial tension running through many of the discussions. Most of the comments appear to be left by whites, though anonymity reigns. Last summer, when Bernard posted news of gunfire (no one was injured) outside XII, an H Street club that attracts a largely black clientele, the item drew more than 70 comments. “Post all the ‘oh it could have happened anywhere’ nonsense you want, bleeding hearts,” sneered one anonymous writer. “This type of crap only happens at joints like XII. . . . Cater to a predominately younger, black, male population, and violence will likely follow.” Another, enraged by the “entitled racist yuppie mentality” of the neighborhood, wrote, “May your home values go to shit and may you each find a Burger King wrapper on your lawn!”

Absent in most of these discussions are the voices of those who have lived in the neighborhood all along. I've been met with abundant kindness since I moved to Rosedale. Still, as I ride beside local residents on the bus or pass them in the street, the knowledge that I’m a sign of change they may have mixed feelings about has made me cautious behind my “Hello.” As I prepared to write this piece, I was struck time and again by people’s willingness to talk to me, a gentrifier who had moved into their neighborhood and was, in essence, asking how they felt about it. Thelma Anderson, a retiree who has lived in the house a few doors down from me since the 1980s, told me she is glad that whites are back and that they don’t show fear. But several longtime residents I spoke with expressed ambivalence. They’re happy to see the neighborhood improving but unsure what their place will be in the H Street neighborhood of the future.

The man who’s probably done the most to re-envision H Street is Joe Englert, a restaurant and nightclub entrepreneur just shy of 50. He recalls that when he arrived on H Street several years ago, after putting his quirky stamp on other parts of the city, “every block had a barbershop or a hair weave operation, a takeout, and a church. Other than that, you didn't have more than three or four businesses per block.” He opened his first club, Palace of Wonders, a tongue-in-cheek burlesque bar, in 2006. Today he has a stake in half a dozen establishments on H Street. Englert’s aggressively funky imprint has made the street an entertainment mecca for people in search of an alternative to clubs with dress codes.

A brash Pittsburgh native who exudes a slightly unruly aura of intense activity, Englert has no patience with hand-wringing over gentrification, or “gentri-fiction,” as he calls it. “The only thing that is constant is change,” he says when he meets me for an interview at the Star and Shamrock, a Jewish- and Irish-themed bar that’s another one of his projects. “This was an Irish street, an Italian street, a Jewish street, then it became a black street. Why would it stop changing? That’s the question. Why would anybody expect things to stay the same, when people live, die, move, improve their lives? I mean, who’s gonna dig in and own the mantle?”

As an agent of change myself, I nod my head in agreement. Walking down H Street, it’s hard not to feel a heady sense of inevitability. Change! Progress! And to hold the conviction that all the choices I make about how I live—the way I keep up my yard, the restaurants and shops I patronize, the kinds of foodstuffs I buy at the local grocery store—are contributions to a joint project of incremental improvement that’s spread among thousands of households.

And then, walking home laden with groceries, I watch a tall teenage boy in front of me drop a crumpled white plastic bag, so casually that it seems it’s drifted from his hand because he forgot he was holding it. It falls onto the sidewalk, where it slowly relaxes into uselessness. It is now a piece of trash. I ponder whether to stoop and pick it up and throw it into a nearby trash can. Wouldn't that constitute a censure not only of him, should he turn around and see me, but of the whole neighborhood, where trash blows into streets and yards and forms middens in alleyways? But wouldn't walking by it be a kind of acquiescence? It’s this sort of minute social calculus that’s the mark of the self-conscious gentrifier, not quite sure of her status in the community.

The assumption, so widely held that it’s regarded as fact, is that gentrification is synonymous with displacement.

Whites aren't the only drivers of gentrification. When I go for a drink at Langston Bar & Grille, a three-year-old soul food restaurant and bar a scant block from my house on Benning Road, at the eastern edge of the H Street scene, the place is full, the cocktails aren't cheap, and mine is often the only white face. Yet it’s whites, not incoming middle-class blacks, who get the attention, as Lance Freeman, a professor of urban planning at Columbia University, observes in There Goes the ’Hood (2006), his valuable study of the attitudes of residents in transitional neighborhoods. The surprise at white faces, he writes, indicates “just how racially isolated many of America’s inner-city communities had become.”

What those faces mean lies at the heart of debates over gentrification. The assumption, so widely held that it’s regarded as fact, is that gentrification is synonymous with displacement. Adding to the subtext of forced relocation are bitter memories of inner-city revival efforts. The federal urban renewal program, engineered to usher the American city into postwar Corbusier-style order and modernity, destroyed some 1,600 black communities in American downtowns between 1949 and 1973, estimates Mindy Thompson Fullilove, the author of Root Shock (2004) and a professor of clinical psychiatry and public health at Columbia. The federal highway program also restructured many cities, razing swaths of poor neighborhoods and providing an easy route along which middle-class whites and blacks who were leaving for the suburbs could still commute to downtown jobs.

Quality studies of the residential impacts of gentrification are few, but those that exist largely don’t support the notion that low-income residents are forced out of gentrifying areas en masse. In the study published in the Journal of Urban Economics, a trio of researchers that included University of Pittsburgh economist Randall Walsh analyzed nationwide Census data and found no such evidence, though they did confirm, unsurprisingly, that newcomers are more likely to be white, college educated, and better paid. Unexpectedly, the analysis also showed that in primarily black gentrifying neighborhoods, black high school graduates are responsible for a third of total income gains as the area’s affluence increases. It’s unclear, however, how many of those beneficiaries are longtime residents and how many are newcomers attracted by gentrification.

Columbia’s Lance Freeman and Frank Braconi, former executive director of the nonprofit Citizens Housing and Planning Council, studied mobility patterns in New York City and found that poor households in gentrifying neighborhoods are less likely to move than poor households elsewhere. They concluded that neighborhood improvements induce residents to stay and that rent control laws—in force in cities including New York and Washington—are quite effective at restraining rent increases in gentrifying areas. (Like Walsh and his colleagues, Freeman and Braconi used data from the booming 1990s. It’s unclear if patterns have changed since the economic downturn.)

On the ground, the changes these studies record are the accretion of individual choices. For the past six years, Amanda Clarke, a black architect who moved to the United States from Jamaica in 1986, has made her home in Rosedale. A soft-spoken 40-year-old who lives three blocks from me, Clarke bought her house in a foreclosure auction in 2004 without even seeing the inside, during the height of the D.C. real estate bubble when she couldn't snag a house elsewhere in the city. A couple of years later, she bought a vacant house across the street and rebuilt it from the ground up, designing it with clean modern lines and lots of light. It’s a bright spot on the block when I pass by. Despite the slow economy, the house attracted multiple offers within days of being put on the market last spring. (The buyer, an Asian-American woman in her thirties who works as a management consultant at Deloitte, moved from a thoroughly gentrified D.C. neighborhood.) Clarke just sold a second rehabbed house, a block from her first project, and is preparing to start on a third.

Clarke knows that the homes she designs are attracting people from outside the neighborhood, but what, she asks, should she do differently? Build less attractive homes? Use inferior materials? “This whole idea of affordable, it’s a tough one. What is affordable? What does that mean? Because if by definition things are changing, property values are going up as a result—just by the mere fact that all the vacancies are being renovated. Are you going to try to hold property values down? Do you renovate at a certain level? Do you lower the level? What do you do?”

Not long ago, Necothia Bowens introduced me to Jacqueline Farrell, who in 1971 bought her house on E Street N.E. from a man she describes as the last white person then living in the neighborhood. Farrell, 61, whom everyone refers to as “Miss Jackie,” is a woman with a pleasantly husky voice and quick laughter known for her cooking. It was a Sunday afternoon, and her niece, Kym Elder, 44, who lives in Maryland and works for the National Park Service, was visiting. Patricia Lucas, 50, who lives across the street and whose father-in-law was the man who desegregated the Rosedale playground, joined us as well, as did Bowens. There was a lot of jocular reminiscing, and talk about the current changes to H Street.

“It looks good,” said Farrell. “It’s improving the neighborhood, but I don’t think it belongs to the blacks anymore.”

Elder chimed in, remarking to her aunt that she recalled the first time she rode down H Street and noticed white faces. “It was a spring night after dark. And I called you on the phone, and I said, ‘Oh, my God, where the hell am I? I’m riding past the Atlas [Theater], and they have little bistros. And they’re not afraid.’”

Everyone in Farrell’s living room was happy to see new storefronts and businesses healing over the scars of the 1968 riots. But they expressed concerns, too. There are rumors that an area high school is going to be converted to a charter school that will require students to apply for admission. Bowens is bothered that the two bars on H Street that mostly attract black patrons, XII and Rose’s Dream, seem to get more scrutiny from the authorities than other bars on the strip. No one wants property taxes to go up. If you’re not planning to leave, the concurrent rise in property values that gentrifiers like to celebrate isn't much consolation.

As for their new neighbors? Well, the early experience of those at Miss Jackie’s house has been mixed. It was some years ago that the first white person in the new wave moved to the block. In their description, the fellow sounds like a poster child for bad gentrifiers. He called the police on his neighbors again and again for a litany of minor infractions and walked his two fearsome Akita dogs through pedestrians on the sidewalk “like he was parting the Red Sea,” Farrell said. Since he left about a year ago—was foreclosed on, is the rumor—the block is peaceful again. But Elder is troubled that when she comes to visit her aunt in Rosedale and says hello to passersby new to the neighborhood, they don’t always return the greeting.

The real friction is with people who have moved in near Brown Memorial African Methodist Episcopal Church on 14th Street N.E., which Farrell and Elder both attend. The newcomers have complained about parishioners parking on the surrounding streets on Sundays and the loud gospel singing that comes from the church. Some, Farrell suspects, get up early on Sunday mornings to park their cars just far enough apart that churchgoers can’t fit their vehicles in the spaces between. A few neighbors have even come into the church and interrupted services. “They came down and they talked to us like we were dogs,” Farrell said. Elder was equally incensed: “In the biblical days, they had people come into the services and try to disrupt them because they were ungodly. Well, literally, we have to have men at the doors of the church now because unfortunately our new white neighbors are saying, ‘Wait! Ya’ll parking? How long you going to be in services?’ I mean, coming into the house of the Lord, screaming and hollering!”

In general, it’s not the changes themselves that bother longtime residents of Rosedale. It’s how and why those changes are happening. In a separate interview, Bowens ruefully conceded that it was whites who “saw the baby ready to be reborn” on H Street. She works as a secretary for a downtown doctor, but noted that business ownership runs in her blood—for years her grandmother ran a restaurant near the Capitol where people lined up for fried fish on Fridays. “I had an opportunity a long time ago to say, ‘You know, H Street is there. No one’s doing anything on H Street. I can go open up a business.’ But because we weren't taught as black people how to do that, we kind of let it sit. . . . That credit word makes us fear.”

The perception that change of others’ making is washing over longtime residents is what’s at the heart of their anxieties. No one but criminals wants fewer police on the streets. No one wants houses and commercial buildings to remain vacant. But neither do they want their community to become a place where they’re the ones who don’t belong. That’s why displacement—though it may not happen as often as people assume—is such a powerful notion.

Bowens, who has gotten active in community politics, wants to be upbeat. She helped start a scholarship fund for area students, and ran, unsuccessfully, for the local seat on D.C.’s neighborhood advisory commission. But she gets pensive when I ask her what she worries about for the future. “In my mind, the changes that are happening still need to continue, but we need to make sure that we embrace people, because if you don’t, it’s going to be—this is a heavy word—but it’s going to be like a holocaust effect. If you get people to come in and take over, it’s going to be like a slavery takeover. You just got people that take over and don’t care about the mindset of the people, and they just try to kill off everything that doesn't belong or look like them.”

For the past few weeks, the rattle and grind of backhoes has filled the air. The dilapidated Rosedale Recreation Center was torn down last fall to make way for a brand-new complex, complete with a library and an indoor swimming pool. Months of red tape delayed construction, but work has finally resumed. Many of the residents I spoke to don’t go to the new bars and restaurants on H Street, but everyone was eager for the recreation center to rise again. Stephon Starke, the man whose father owned a liquor store during the riots, teaches boxing to kids there. It’s the heart of the community and a monument to its history.

Hearing my neighbors talk of the day the recreation center would reopen, I saw a gulf between the way they perceived it and the way I do—as a boon to my property value, primarily. Some gentrifiers move in and stay, but many, like me, have one foot outside the neighborhood from the start, anticipating the day when a new job or the birth of a baby who will grow up and need to attend a good school will prompt us to put a “For Sale” sign in the front yard. I may not be here long enough to see the rec center completed a year from now, let alone send my own children, when I have them, off to the pool. No matter how you measure transience on that spectrum of urban morality, it separates me from my neighbors.

But the possibility of goodbye is no excuse not to say hello on the street.

* * *

Sarah L. Courteau is literary editor of The Wilson Quarterly. Photo courtesy of Flickr/Steffi Reichert