No Reservations: The Rise of Indigenous Cinema

– Elizabeth Peet

What the rise in indigenous filmmaking means for the future of our understanding and appreciation of native cultures all over the world.

In 2001, something extraordinary happened in the world of cinema. Awkwardly mingling with glamorous Hollywood titans from Nicole Kidman to Sean Penn at the 54th Cannes Film Festival was a quiet, humble Canadian Inuit director named Zacharias Kunuk. That year, Kunuk’s film, Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner, became the first indigenous-language film to scoop the prestigious Camera d’Or prize for best feature film. Kunuk was as surprised as anyone at the reception of his film, which retells an ancient Inuit legend of two hunters engaged in a bitter and violent feud in the Canadian arctic. “We made it for an Inuit audience,” he later said. “I never expected that outside countries would be so interested. It never even crossed my mind.”

Almost 15 years later, indigenous films are slowly climbing their way into the mainstream. As Sophie Mayer writes in Sight and Sound magazine, this could have profound implications for how we appreciate and better understand native peoples and cultures — much as film has illuminated cultural peculiarities throughout the world.

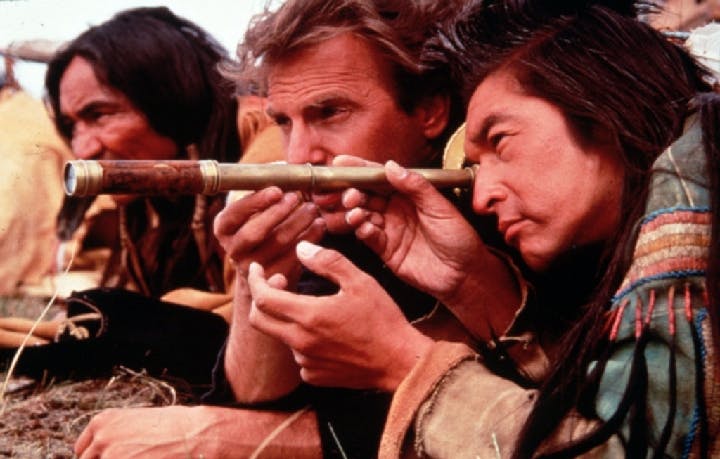

Cinema has always had a power to deepen our knowledge about the past. Public understanding of the Holocaust has been greatly enriched by films, such as Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List (1993) or Roman Polanski’s The Pianist (2002). But there has long been a tendency for films focusing on the experiences of indigenous peoples to be period dramas — these are a people who once were, and now are not — and produced by nonindigenous filmmakers. Consider two much-heralded films from the early 1990s: Michael Mann’s The Last of the Mohicans (1992) and Kevin Costner’s Dances with Wolves (1990), the latter of which won the Academy Award for Best Picture — though not before New Yorker film critic Pauline Kael memorably panned the film as “a kid’s daydream of being an Indian.”

The way that indigenous communities have been presented to Western audiences in films has reenforced continued misperceptions and stereotypes of indigenous cultures, many of which are branded in the popular imagination as perennially stuck in the past, with dated and traditional ways of thinking incompatible with the modern world. These misperceptions are highlighted in a 2013 report published by La Trobe University, which lists various erroneous but widely-held ideas of Australian aboriginals — that Australian indigenous people were “simple and uncivilised,” that they somehow “cannot look after themselves,” and that “all stories about indigenous people are about their failures.” Similarly, negative stereotypes continue to underscore many people’s perceptions of American Indians, with widely held images of decaying, ‘backward’ cultures living meaningless existences on reservations.

All of this could change as modern, indigenous-made cinema increases in popularity. The Origins Festival of First Nations, a biennial event first held in London in 2007, celebrates modern indigenous culture through a series of film, theater, and art performances. This year’s festival celebrated portrayals of the recent past for indigenous peoples, screening movies from the early 2000s, including Whale Rider, a drama focusing on a Maori community in New Zealand, and The Tracker, which observes the interactions between an Australian Aboriginal and a white policeman. Both of these films came out to critical acclaim in 2002, a year which Sophie Mayer has described as “the key date for fourth-world cinema,” when indigenous cinema met global success.

This year’s festival also screened Sydney Freeland’s Drunktown’s Finest (2014), which took last year’s Sundance Film Festival by storm. The film, made by a prominent Navajo auteur, focuses on the hardships and struggles faced by young Navajo teenagers living on an Indian reservation. Set in the present day, the film breathes relevance and vitality into the indigenous cultures it represents — we are still here.

Politically speaking, the last several decades have produced major milestones for native peoples across the world. In 1995, the New Zealand government formally apologised to a Maori tribe for stealing 500,000 hectares of land 130 years earlier, and has since provided them more than NZ$1 billion in compensation. In 2008, the Australian government formally apologised for the stolen generations of Aboriginal children who were taken from their birth parents and placed with white families or in white-run orphanages. A few months later, Canada apologized to its own first nations, and has compensated the native children abused in its residential schools to the tune of $2 billion. Even in the United States, the 2010 defense appropriations bill offered a short apology to Native Americans.

A clear trend of towards reconciliation and interaction with native communities has arguably been bolstered by a greater representation of indigenous cultures within the broader popular culture. “Taking representation, production and even distribution into its own hands,” writes Mayer, “twenty-first century indigenous cinema is resurgent.” This resurgence is already changing our perceptions of native peoples for the better.

* * *

The Source: Sophie Mayer, “Breaking your reservation: the rise of indigenous cinema,” Sight and Sound Magazine, June 10, 2015.