'Riding the Tiger' through Fields of Corn and Soy

– Penny Loeb

While this patch of America’s heartland may seem far removed from the outside world, international trade is vital to keeping the plows in motion. Amid tariffs and market tumult, these communities wait and watch, worry and hope.

It is a summer morning in Corning, an agricultural town, population about 15, in the far southwest of Missouri. Morris Heitman, 73, sits at a picnic table on the farm his great grandfather settled when he emigrated from Germany in 1878. A breeze from the maple trees that Heitman planted as a teenager brushes off today’s heat warning. The tractors and harvesters that he, his brother, and an employee use to farm one field of corn and one of soybeans stand close. Just to the west is a levee on the great Missouri River. On nearby tracks, “Warren Buffett’s train” (as locals call the BNSF freight railway, which the billionaire’s company owns) occasionally passes, its empty cars waiting to be filled with coal when it reaches Wyoming.

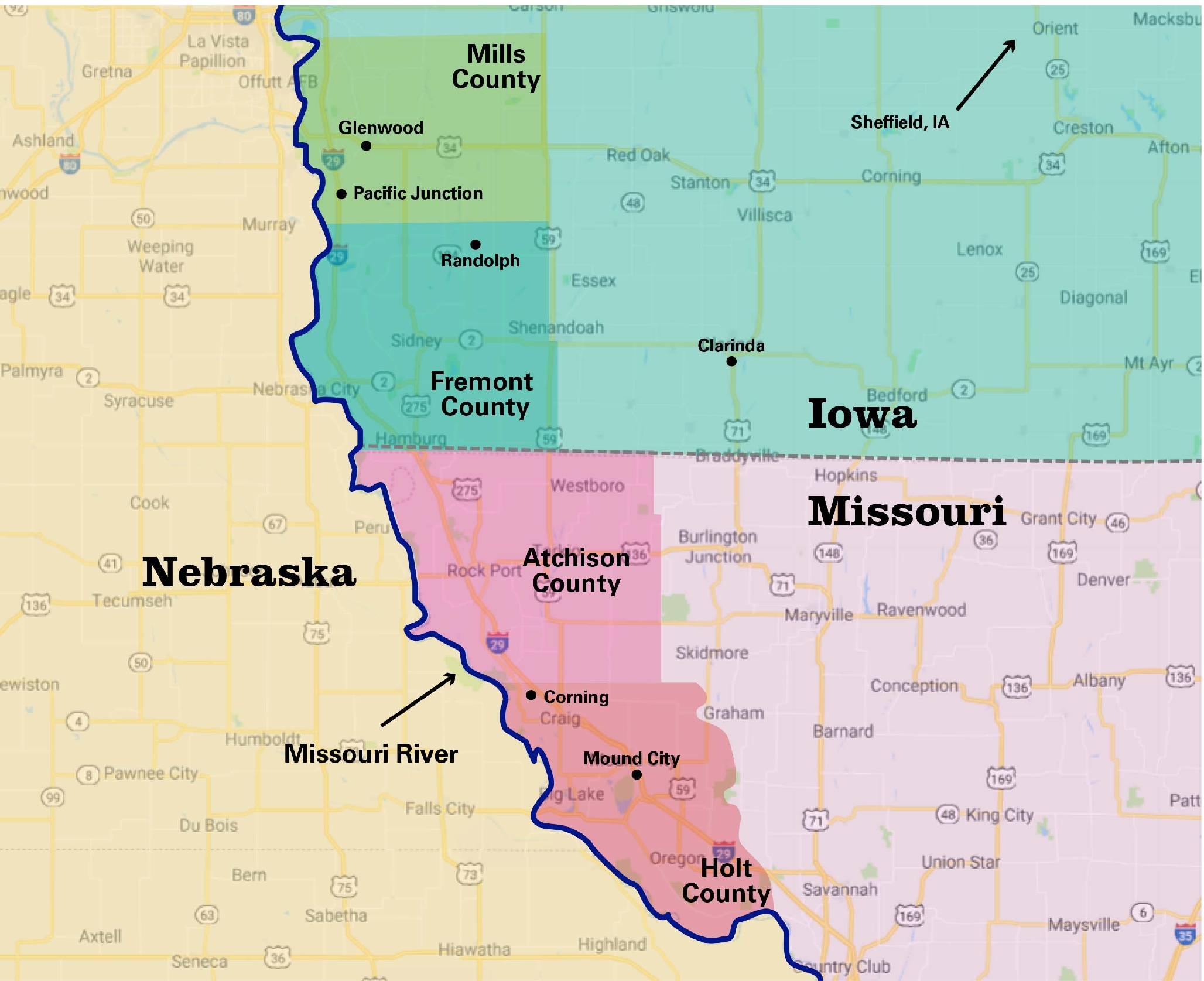

This rural corner of the country is a bit of a geological world unto itself. Eighty miles of fertile soil stretch north along the river in Holt County, where Heitman farms, through Atchison County and into Fremont and Mills Counties across the state line in Iowa. Tabletop fields extend east to the gentle mounds and inviting folds of the Loess Hills, a unique formation of blown clay soil. Corn and soybeans cover seemingly every inch of tillable land, whether flat or hilly, creating a postcard of the so-called U.S. Corn Belt. At harvest time, corn and soybeans go directly into the grain elevators that dot nearly every community, or into silver-colored bins on farms, awaiting favorable prices. More than half of the corn from this area will become ethanol. Most counties also have hog farms in their least populated spots.

While this patch of America’s heartland may seem far removed from the outside world, international trade is vital: The U.S. is the world’s top producer of corn, and while only 14 percent is exported, that is still the largest quantity in the world. The country exports more than 60 percent of the soybeans it grows and competes with Brazil at the top in that category. Iowa and Missouri play outsize roles in these statistics; they are both among the top producers of corn and soybeans in the country, with Iowa ranking number one in corn production and number two in soy. Mexico, the country’s third-largest trading partner, has long been the top importer of U.S. corn and is the second-largest importer of U.S. soybeans. That’s behind America’s top trading partner, China, which bought well over half of soybean exports in 2017 – worth $12 billion – for use as livestock feed and for cooking oil.

But on July 6, Beijing imposed a stinging 25 percent retaliatory tariff on soybeans and other key U.S. exports chosen to hit President Donald Trump’s Midwest-based supporters in particular. Mexico, having already slapped its own retaliatory tariffs on $3 billion worth of American goods is reportedly studying tariffs on both corn and soy. Here, among the peaceful fields that have stayed in the same families’ hands for generations, farmers and businesses are trying to make a living amid concern and confusion over the fate of NAFTA and the trade wars ignited by the United States.

“There is apprehension, I think, in the farming community,” says Heitman, who spent nearly 30 years as county director of the Farm Service Agency at the U.S. Department of Agriculture. He is now a director of the Missouri Corn Growers Association. “I just saw a headline that the Secretary of Agriculture, Perdue, indicated that the president told him this would not be a harmful situation for the farm population. I don’t know. It’s a way of doing business, country to country, that I’m not familiar with – and it’s a style that I’m not real comfortable with.”

“Some people out here say we’re ‘riding the tiger,’” he chuckles, referring to President Trump. “The tiger’s going to do what he’s going to do, and we’re just a part of it.”

'Scary as Hell'

On the campaign trail and since, Trump has excoriated NAFTA, the 1994 free trade deal between the U.S., Canada, and Mexico, as responsible for an exodus of U.S. jobs and “the worst trade deal ever made.” He has also vowed to slash the $375 billion trade deficit with China and put an end to Beijing’s predatory practices. Tariffs, he maintains, will bring these top trading partners to the table, extract concessions, and help “make America great again.” Along the way, many experts have warned that trade wars will inflict major pain on U.S. industries, including those that keep Missouri and Iowa running. Now, talks to renegotiate NAFTA are stalled amid hardline U.S. bargaining, and business is far from booming for farmers.

Commodity markets on the Chicago Board of Trade went into a tailspin in June and early July as traders braced for, and then reacted to, the imposition of Chinese tariffs. Soybean prices fell to a near-decade low, while corn prices also sank amid market uncertainty – inflicting a big hit to farmers in the U.S. heartland, whose net income had already been predicted to drop this year. The full extent of the losses, estimated at billions of dollars for corn, wheat, and soy, will not be known until harvest in a couple of months. For now, at least, prices seem to have bottomed out, rising in early August amid news of progress in trade negotiations.

On July 24 – a day in which Trump visited Missouri and two days before a trip to Iowa – the president pledged $12 billion in emergency aid for farmers. The move was stridently criticized by lawmakers in Washington, including the president’s fellow Republicans, and derisively called “farmer’s welfare” by some. Here, most people think the funds will help, but it is certainly not the back-to-normal trade they want. “Scary as hell” is how Missouri Farm Bureau President Blake Hurst characterizes it, “because it’s a pretty good indication there will be no negotiated solution anytime soon.”

And so, communities and farmers continue to wait and watch, worry and hope.

Trade Hits Home

An hour’s drive north from Heitman’s farm, in Glenwood, Iowa, trade uncertainties furrow the brows of business owners whose livelihoods are built on supporting the area’s farming. This county seat, with a population that has held steady at about 5,000 for three decades, has been a crossroads of the local agriculture industry since Mormons founded it in 1848. In 1899, C.E. Dean opened Glenwood State Bank to serve farmers. Now, Dean’s great-grandson, Grant, runs the bank. With four white Corinthian columns out front, it faces historic Courthouse Square, where shoppers flock every Wednesday afternoon in summer for a farm market.

“In agriculture, the more markets and the more places you sell crops, the better,” Grant Dean says. “NAFTA – if we have restrictions, that would impact the vast majority of my customers.” More than half the farmland in the area is rented, he explains. If grain prices stay low, farmers will ask for lower prices when they negotiate rent in early September. Reductions in rent would cut retirement income of older owners, he says.

Albeit less directly, tariffs on steel have hit this area, too. On May 31, citing national security concerns, the White House slapped a 25 percent tariff on steel from Canada, the largest exporter of the metal to the U.S., as well on EU and Mexican steel. Canada has since retaliated in kind. In the tit-for-tat, U.S. farmers and businesses have had to cope with rising costs for domestic steel, as mills struggle to keep up with demand.

Four miles from the bank, the price hike has hit Vinton Fertilizer and Equipment in Pacific Junction. This throwback sells most every hard-to-find farm supply, from nuts and bolts stored in hundreds of bins behind the counter to fertilizer, herbicides, and riding mowers. Burl Vinton says he has watched prices jump nearly 15 percent for the steel culverts he sells.

But despite the turmoil over trade, Vinton, like many others in these communities, still has confidence in Trump’s tactics. Fixing NAFTA could take a while, he concedes, his suspenders sagging as he sits back in his office chair. “[Trump] has good people working on it. I think it will be a lot fairer down the road. I have a real good feeling. By harvest time, prices may not be back where they were, but they will be a lot better than today... That is, if we have anything to harvest.” Five to 10 percent of the fields in the area are under water now due to flooding from the river. Then again, the crop loss might be an advantage if markets are limited. (No matter the shape of trade policy, Mother Nature always has a major role to play in determining farm income).

The steel-price hike was even worse for family-owned Sukup in Sheffield, Iowa. The company, which says it is the world’s fastest-growing grain bin manufacturer, now reports paying 30 percent more for the U.S. steel it has always used. “We do a lot of business with Canada – got good dealers up there. We have good dealers in Mexico, too,” Vice President Steve Sukup says. “So this really concerns us if we don’t maintain those strong partnerships.”

'Short-Term Pain'?

Besides steel, one of the first retaliatory tariffs to impact farmers here was on pork. Then, in July, a second round of duties on the meat were levied by China as well as Mexico, the largest market for U.S. pork. Iowa is the top pork-producing state in the nation.

Up a gravel road near Clarinda lives Curtis Meier, a director and the only two-time president of the Iowa Pork Producers Association. His family farms 3,000 acres of corn and soybeans, raises 2,000 beef cattle, and sends about 2,500 hogs a year to meat-processing giant Tyson Foods. Wearing a John Deere hat, Meier sits at his kitchen table and pulls out stats from the pork association. Prices for lean hog futures have sunk in the past several months and there are new fears of a glut of meat in the domestic market. Meier happened to be in China on business when the country announced its first round of pork tariffs. He shows photos on his cell phone from the residence of U.S. Ambassador Terry Branstad, who was previously Iowa’s governor. Over the past decade, Meier has traveled to Japan, Singapore, Malaysia, Central America, and the Dominican Republic in search of new business.

Like many farmers, he feels caught in the middle of the trade wars, but holds out hope that things may be fairer in the end. “It’s high time. There’s been a trade deficit long enough,” he says. “This might work to our advantage… We don’t know. I’ve heard the statement ‘short-term pain, long-term gain.’”

But at what point, exactly, does short-term pain go too far?

In Randolph, Iowa, about half an hour northwest, fifth-generation farmer Julius Schaaf has spent more than a decade developing new markets and new uses for corn. He was previously chairman of both the U.S. Grains Council and Maizall, an alliance of corn farmers in Argentina, Brazil, and the U.S. focused on promoting access to genetic science and technology to help ensure global food supply.

Does NAFTA need to be upgraded? Sure, Schaaf says: “My high hope is that it’s not completely abandoned and we have to start over. If you try to go to a bilateral trade agreement with just ourselves and Mexico and ourselves and Canada, you’re talking about a years-long process. I’m afraid in that time we will lose a lot of market access for U.S. crops into Mexico and into Canada.”

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce estimates that both Iowa and Missouri would be among the states hit hardest by NAFTA withdrawal, with the business group noting that about half of each state’s total exports are bound for North American neighbors.

International markets have shifted already. Brazil is expected to send 2.1 million more tons of soybeans to China to offset a loss of 6.8 million from the U.S., according to July’s USDA World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates.

“I just know it takes a long time to overcome market destruction,” Schaaf adds. “It won’t be over in six months. It will take a decade or longer to recover.”

Faith in the President

A closely related question of time – When will the “tiger’s ride” come to an end? – now regularly faces Chuck Grassley, the senior senator from Iowa.

“Could be tomorrow or it could be next year. And if it’s next year, it will be catastrophic in the meantime,” he said after a standing-room-only town hall in early July. “People are calling who support the president very strongly, and probably voted for him, but they still have concerns. It’s so new; we have conflicts on international trade, tariffs versus tariffs involving NAFTA, and South Korea, China, and Europe, all at the same time. We’ve always had trade issues, but they’ve been very minimal compared to what we have now.”

“About the only way you can have confidence is if you have faith in the president’s ability to negotiate,” the Republican senator added. “But they still have questions at the same time. That’s what I’m hearing from my constituents.”

Concern has also prompted local farm leaders to bring their questions directly to Washington. Farm Bureau President Hurst, who lives among a forest of wind turbines on the Missouri side of the state line, isn’t encouraged by what he learned during his recent meetings in the capital.

“We heard from a couple trade officials. We heard from somebody on the economic council,” he says. “No, nothing encouraging. Very clear that these negotiations are going to take a while – to the extent that there are negotiations going on. It was not clear that there are any negotiations.”

“Administration officials seemed to say, ‘It’ll be better when it’s over, but it’ll take a while until it’s better,’” Hurst recounts. “That’s not very encouraging if you’ve got a bunch of soybeans and you’ve just seen the price go down $2 a bushel.” He should know; his nephew is president of the Missouri Soybean Association.

Has the fallout weakened farmers’ support for the president, who insisted in March that trade wars were “good” and “easy to win”? Morning Consult polling shows that the president’s approval rating has slipped three percent from January 2017 to June 2018 among voters in both Missouri and swing state Iowa. With less than 100 days until the midterm elections, Congressman David Young, a Republican representing southwest Iowa, is in a toss-up race with Democrat Cindy Axne of West Des Moines. He has expressed strong criticism for Trump’s trade wars following announcement of the $12 billion support plan.

Where 'the Ride' Ends

While Hurst, 61, is a Washington veteran, Dylan Rosier, 30, a member of the board of the Missouri Corn Growers Association, has just begun his political education. On land above Mound City, Rosier, his father, and brother farm 6,000 acres settled by his great-grandfather. NAFTA opened up the Mexican market for their white corn, which grows well in certain soil on the farm.

Atop a hill between Rosier’s house and his parent’s house on one side and a small church and cemetery on the other, a huge steel building houses the third-largest harvester made by John Deere, price tag about half-a-million dollars. Nearby, soybeans and corn are stored in Sukup bins so large, they make him look like a child’s action figure.

“Uncertainty in the market has been the biggest thing so far. Nobody knows what [the administration’s] goals are,” Rosier says. “We are already at the break-even point or less for most people. You can feel it around in the countryside, talking to people. If we don’t take care of NAFTA, that will hurt our business and farmers as a whole.”

In mid-July, Rosier spent two weeks in Bulgaria and Italy with Missouri’s Agricultural Leaders of Tomorrow program. He says he saw first hand how the European Union supports farmers on crops and capital purchases. “I would rather grow a crop hand over fist than rely on the government to subsidize us,” he insists. “I realize what Trump is doing, trying to level the playing field for America… but what we really need is to get through this and open up the world market in a big way.”

While Rosier doesn’t profess to know how the tariff wars will end or what will give NAFTA negotiations the momentum to cross the finish line, he believes he needs to be part of the solution. “It’s pretty important, especially for people my age, to get involved,” he says. “Now, legislators are so far removed from farming, it’s up to my generation to tell them what’s impacting us.”

Rosier still has 25,000 bushels of soybeans from last year’s crop. “We would definitely be taking a hit with what we have left,” he says, scanning the fields.

For now, Rosier can only hope that the “ride of the tiger” ends favorably, and soon.

***

Penny Loeb (@tutalibi) is a veteran of investigative teams at Newsday and U.S. News & World Report. She is the author of Moving Mountains: How One Woman and Her Community Won Justice from Big Coal.

Cover photo: Sukup grain bins stand beside fields of crops.