Spring 2011

So Goes The Nation

– Jason Sokol

American itself has been quite "Southern" all along. "Neither the South nor America can ever be truly understood as anything but a part of the other."

James C. Cobb is a don of Southern historians, and his The South and America Since World War II is impressive for its scope and sweep. No important event in the last 70 years escapes his eye: the shifting terrain of party politics and the rise of the civil rights movement, the relationship between race and regional identity, the unchecked strength of the South’s corporate elite and the sad plight of its working classes, the popularity of NASCAR and the enduring power of the blues, the devastation of Hurricane Katrina and the South’s role in the election of Barack Obama. The problem is that all of these individuals and episodes merely dance across the pages—and then they are gone.

Cobb covers territory that many others have explored—though few have attempted so thorough a synthesis, or brought the story of the Southern past up to the present. Those familiar with his prodigious output—including The Selling of the South (1982), The Most Southern Place on Earth (1992), and Away Down South (2005)—will find him sometimes recycling it, but also, at his best moments, expanding upon a career’s worth of insights.

Cobb offers one major interpretive frame: the idea that America itself has been quite “Southern” all along. “Neither the South nor America can ever be truly understood as anything but a part of the other,” he writes. He is most passionate when eviscerating writers and scholars—economist and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman and political scientist Thomas Schaller chief among them—who have insisted that the South is a land apart. Long after Southern states had buried their Jim Crow signs and jumped into the nation’s economic and political mainstream, such observers continued to portray the region as distinctive because of its racially tinged political conservatism. To Cobb, they are but the latest incarnations of Northern writers who, in the decades after World War II, established their own moral righteousness by divorcing the nation from Dixie and turning a blind eye to the fact that racism was an American trait rather than a Southern aberration.

Cobb makes a good case for the primacy of the Southern economy in understanding developments in race, politics, and society. To image-conscious white leaders during the early 1960s, Martin Luther King Jr. was a “fearsome figure” indeed. The mayor of Augusta, Georgia—a segregationist hotbed—capitulated to the integration of lunch counters and theaters in 1962 only because “we were afraid they would bring in Martin Luther King.” As Cobb shows, Southern business leaders finally concluded that “their desire to keep the South racially southern must give way to their goal of making it economically American.” When Cobb pushes himself to make strong claims like that, he is best able to illuminate the dynamic link between the South and America.

Though Cobb is a historian, he offers more original observations about the present than he does about the past. He places the horror of Hurricane Katrina within a minihistory of New Orleans, expertly condensing the city’s economic, racial, and political ordeals since World War II. And he notes that in the 2008 presidential election, Barack Obama aroused “intensified white resistance” within certain Southern enclaves. There were not many counties where Obama polled considerably worse than Democratic candidate John Kerry had in 2004. The South—particularly Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Tennessee—was home to 97 percent of those counties where he did. Yet the other nine states of the former Confederacy offered surprising degrees of support to the man elected America’s first black president. To Cobb, this transformation in the region’s racial politics outweighs any lingering resistance.

Cobb concludes by returning to the theme of the South and the nation. “The fundamental reality of Dixie was every bit as ‘American’ in 1941 as it is today,” he writes. This is an intriguing line of argument. But the problem is that he means to make a comparative point—and he presents only half of the picture. Nearly everything Cobb posits about the North and the West is filtered through quotations from New York Times and Newsweek reporters. One wishes his claims were much more richly documented and textured. This lifelong Southerner is content to remain in his Southern perch while making assertions about the nation writ large.

My hope, as a Northerner with a keen interest in the South as well as the North, is that Cobb will one day fully apply his acumen somewhere above Virginia or beyond Texas. For now, we are left with his compelling insights into Southern history alongside his surface impressions of Northern history—not a bad proposition with so learned a guide as Cobb, but not a profound one either.

* * *

Jason Sokol teaches African-American history at Harvard University. He is the author of There Goes My Everything: White Southerners in the Age of Civil Rights (2006).

Reviewed: "The South and America Since World War II" by James C. Cobb, Oxford University Press, 2011.

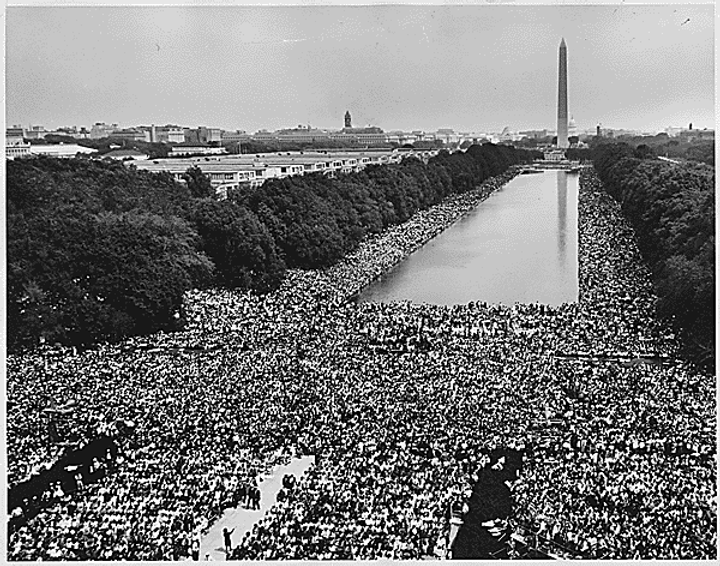

Cover photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons