Star Trek's Underappreciated Feminist History

– Shannon Mizzi

Starfleet women were the futuristic version of Helen Gurley Brown’s 'Single Girls' —they did not cook, clean, have kids, or get married. They were competent professionals.

Despite airing for only three seasons — from 1966 to 1969 — Star Trek is widely considered one of the most culturally influential series in American television history. In many ways it was a progressive offering, featuring a multi-racial cast, and male and female characters who worked together as equals. In the years since it went off the air, one criticism it has been repeatedly charged with repeatedly is sexism. In a recent article in Frontiers, Patricia Vettel-Becker contextualizes the position of female characters on the show and examines not whether Star Trek was sexist, but why it portrayed women the way it did.

Star Trek made its debut in the fall of 1966 on NBC. This was its second incarnation; the network had turned down the original pilot for the series, partly because certain female characters had not tested well with audiences. A female character named “Number One” induced a particularly strong reaction. “Not only did men hate the character, but women hated her as well, calling her ‘pushy’ and ‘annoying’ and criticizing her for ‘trying so hard to fit in with the men,” writes Vettel-Becker. Any hint of “masculine” qualities in female characters was strongly rejected by test audiences. The show’s producers were instructed to make some drastic changes if they wanted the show to make it to air.

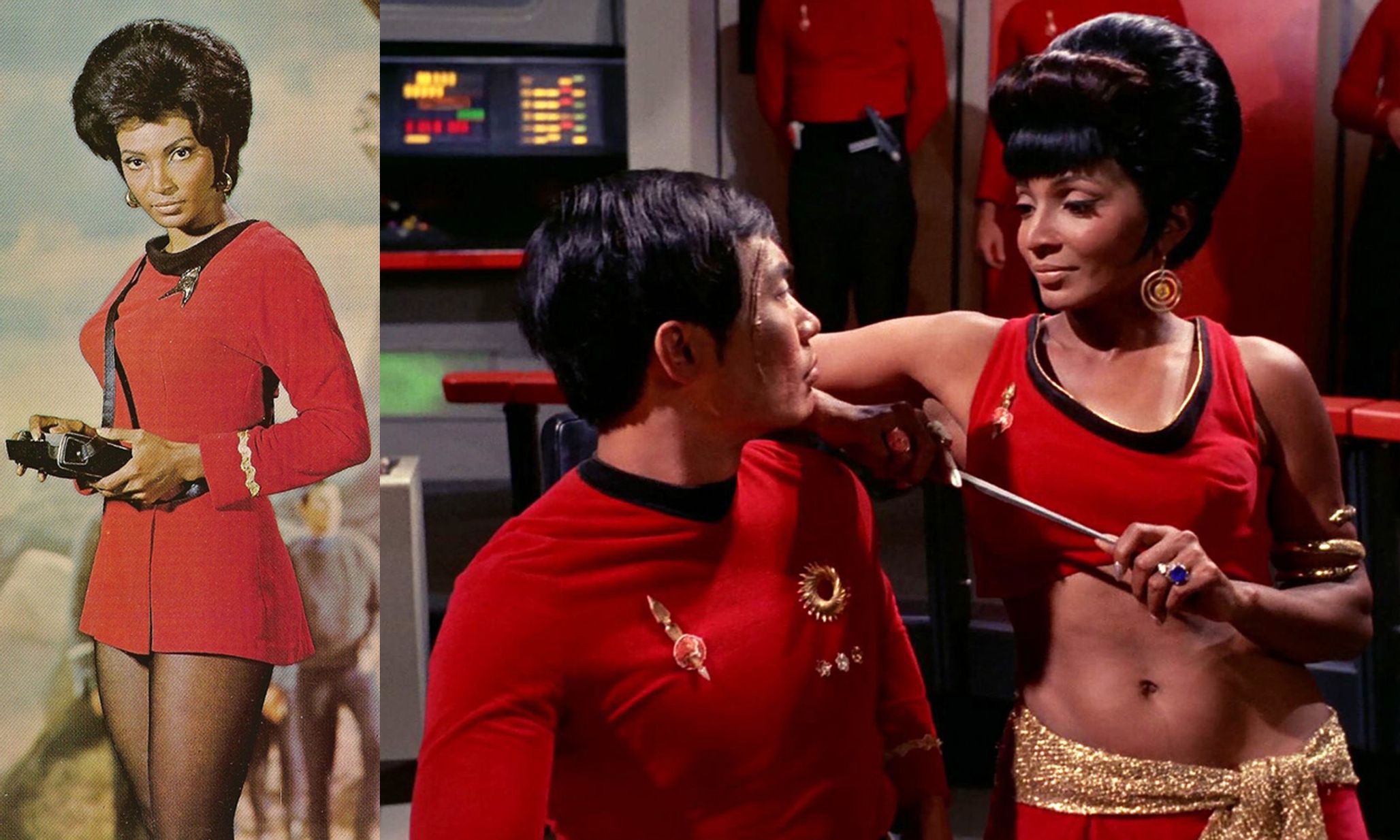

Some of the biggests changes made were to the characters’ costumes, which had originally been unisex. When Star Trek finally premiered, “the women of Starfleet wore short, close-fitting tunics that emphasized their feminine curves and highlighted their legs, their thighs sheathed in transparent black hose, their calves and feet in snug high-heeled boots.” Vettel-Becker argues that because the women of Star Trek were engaged in an occupation so vastly different from what was socially acceptable at the time — the first female candidates for NASA’s astronaut program were not accepted until 1978 — it was essential that they appear as feminine as possible to quell any social anxieties dredged up by their existence. The costumes and mannerisms of Star Trek’s female characters, writes Vettel-Becker, “may have soothed anxiety over the possibility of de-feminization by appearing and acting ultra-feminine, overcompensating for their relinquishing of domesticity and their adopting of scientific or technological career fields.” This ultra-femininity was expressed through both clothing and romantic dependence on male characters.

“Starfleet women were the futuristic version of Helen Gurley Brown’s ‘Single Girls,’” writes Vettel-Becker. “They did not cook, clean, raise offspring, or get married … they are characterized as competent professionals.”

The series’ female characters often took on nurturing roles in addition to the duties associated with their occupations. This , it seemed, was what was required to keep American audiences happy while they were experiencing a profound upheaval in gender relations in their daily lives. This was a time when the proportion of women in the workforce was steadily increasing, the women’s rights movement was gaining traction and visibility, and many women felt that marriage and a retreat to domesticity could be postponed or refused in favor of career advancement. The idea of men and women working alongside one another in the workplace made Americans of both genders uneasy.

Although the show is often retrospectively charged with sexism, Vettel-Becker asserts that the women of Star Trek actually constituted strong role models for female fans in the 1960s. “Starfleet women were the futuristic version of Helen Gurley Brown’s ‘Single Girls.’ They did not cook, clean, raise offspring, or get married,” she writes. “Despite the visual objectification of [female characters like] Rand and Uhura, they are characterized as competent professionals.” Female commanders on par with Spock made appearances every so often from rival civilizations. For female viewers, “such characters would be a fantasy projection, a way for them to imagine themselves in such a position — commanding a starship and its crew while enjoying the pleasures of fashionable attire, comfortable furnishings, and sexual companionship on one’s own terms.”

When interviewed in later years, many of Star Trek’s lead actresses did not see their costumes as demeaning or sexist, saying instead that to them mini-skirts were a sign of sexual liberation rather than oppression. Indeed, young women in the ‘60s were beginning to adopt miniskirts as a fashionable expression of modernity and freedom from the domestic sphere. Many were encouraged by contemporary books like 1962’s Sex and the Single Girl (written by Helen Gurley Brown, who became the editor of Cosmopolitan magazine in 1965) to use their femininity to get ahead in the workplace. “A masculine woman will never be taken for a man in a man’s world,” wrote Gurley Brown, “she will be considered a failed woman.” Vettel-Becker sees this theme as omnipresent in Star Trek writing “whether inherent, an act to play, or a mixture of both, femininity was one tool 1960s women had that men did not, and they did not want to lose it. Only one of the two major markers of femininity could be sacrificed, either domesticity or beauty, but not both.” Examined from the vantage point of today’s third-wave feminism, the revealing outfits worn by the women of Star Trek can seem like instruments of objectification, but Vettel-Becker argues that many women viewed them as tools for getting ahead rather than something demeaning that they were forced to wear.

Star Trek retained a loyal female fan base throughout its first run, and women played a great part in the massive letter-writing campaigns that took place before and after its third season, designed to convince NBC to keep the show on the air. Many women wrote fan letters expressing gratitude to the show’s creators saying that the series inspired and encouraged them to pursue careers in technology and the sciences. As Vettel-Becker writes, “although critics have tended to regard the women in Star Trek as little more than sex objects on display for the pleasure of men … I would argue that in Star Trek, beauty functions as a metaphor for humanity, and therefore it is beauty that humanizes outer space, that soothes anxiety over the terrifying unknown.”

The Source: “Space and the Single Girl: Star Trek, Aesthetics, and 1960s Femininity” by Patricia Vettel-Becker, Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, 2014.