The Arab Tomorrow

– David B. Ottaway

The Arab world today is ruled by contradiction. Turmoil and stagnation prevail, as colossal wealth and hyper-modern cities collide with mass illiteracy and rage-filled imams. In this new diversity may lie disaster, or the makings of a better Arab future.

OCTOBER 6, 1981, WAS MEANT TO BE A DAY OF CELEBRATION in Egypt. It marked the anniversary of Egypt’s grandest moment of victory in three Arab-Israeli conflicts, when the country’s underdog army thrust across the Suez Canal in the opening days of the 1973 Yom Kippur War and sent Israeli troops reeling in retreat. On a cool, cloudless morning, the Cairo stadium was packed with Egyptian families that had come to see the military strut its hardware. On the reviewing stand, President Anwar el-Sadat, the war’s architect, watched with satisfaction as men and machines paraded before him. I was nearby, a newly arrived foreign correspondent.

Suddenly, one of the army trucks halted directly in front of the reviewing stand just as six Mirage jets roared overhead in an acrobatic performance, painting the sky with long trails of red, yellow, purple, and green smoke. Sadat stood up, apparently preparing to exchange salutes with yet another contingent of Egyptian troops. He made himself a perfect target for four Islamist assassins who jumped from the truck, stormed the podium, and riddled his body with bullets.

As the killers continued for what seemed an eternity to spray the stand with their deadly fire, I considered for an instant whether to hit the ground and risk being trampled to death by panicked spectators or remain afoot and risk taking a stray bullet. Instinct told me to stay on my feet, and my sense of journalistic duty impelled me to go find out whether Sadat was alive or dead.

I wove my way through the fleeing crowd and managed to reach the podium. It was pandemonium. Wild-eyed Egyptian security men were running every which way, trying to apprehend the assassins and attend to the scores of foreign and local dignitaries present, seven of whom lay dead or dying. The utter chaos allowed me to get close enough to witness another unforgettable scene: Vice President Hosni Mubarak emerging from beneath a pile of chairs security men had thrown helter-skelter over him for protection. He was brushing dirt off his peaked military cap, which had been pierced by a bullet.

Mubarak, lucky to be alive, pulled himself together admirably that day to take over leadership of the shaken Nile River nation. But Egypt and the rest of the Arab world would never be the same. For centuries, Egypt had prided itself on being the center of that world. Seat of a 5,000-year-old civilization that at times had thought of itself as umm idduniya, “mother of the world, ” it was the most populous and economically and militarily powerful Arab state, a center of culture and learning that supplied physicians, imams, and technical experts to other Arab nations. Under Sadat and his predecessor, the pan-Arab hero Gamal Abdel Nasser (1918–70), Egypt had reasserted its primacy as the Arabs broke free of colonial rule after World War II and entered an era of soaring hopes. Sadat had even begun some pioneering reforms—allowing opposition political parties, implementing market-oriented economic changes—that might have rippled through the Arab world had he lived. Though many reviled him for signing a peace treaty with Israel in 1979, Egypt remained the most dynamic force in Arab affairs.

Mubarak’s accession would bring an abrupt end to Egypt’s preeminence. Cautious and unimaginative, the former air force commander has never in his 29-year reign come close to filling the shoes of his predecessors. Afflicted by health problems, he will turn 82 in May and is not expected to reign much longer. Cairo is awash with speculation about who will replace him. Its discontented intelligentsia is debating intensely whether Egypt any longer has the wherewithal, or vision, to shape Arab policies toward an immovable Israel, a belligerent Iran, fractious Palestinians, or an imposing America, much less grapple with the Islamist challenge to secular governments.

During the Mubarak years, other voices and centers have arisen, particularly on the western shores of the Persian Gulf. There, monarchies once thought quaint relics of Arab history—including Qatar, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates—have taken on new life. The accumulation of massive oil wealth in the hands of kings and emirs amid soaring demand and prices over the past few decades has given birth to a far more diverse and multipolar Arab world. It has made possible innovations in domestic and foreign policy and supplied vast sums for the building of glittering, hyper-modern “global cities” that lure Western and Asian money, business, and tourists away from Cairo.

As the Mubarak era nears its end, Egyptians are not alone in wondering whether a new and more dynamic leader will restore the nation to its central role and take the lead in giving the Arabs a stronger and more united voice in global affairs. Whether any Egyptian leader, or for that matter any Arab leader, can rise to lead this fragmented world will be a central issue in the years ahead. Another is whether Arab unity is any longer a desirable goal.

Arabs have long shared an unusually strong sense of common identity and destiny. The Arab states, unlike those of Western Europe, Africa, Asia, or Latin America, are bound together by a common language and shared religion. They have a border-transcending culture rooted in 1,400 years of Islam, with its memory of the powerful caliphates based in Damascus and Baghdad. With the exception of Saudi Arabia, which escaped the European yoke, they also share a history of fervent anticolonial struggle against France and Britain that began with the crumbling of the Ottoman Empire during World War I. The Ottomans had ruled the Arabs for nearly 500 years, deftly dividing them while governing with a relatively light hand. The Arab Revolt (1916–18) against the Ottoman Turks, led by the emir of Mecca, Sharif Hussein ibn Ali, and abetted by Britain’s legendary Lawrence of Arabia, ignited the dream of a reunified Arab nation.

But the victors of World War I had different ideas. The League of Nations put the vanquished Ottoman Empire’s provinces in present-day Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine under French and British mandates, giving fresh impetus to the Arab awakening. During World War II the European rulers cynically encouraged hopes for independence, intent on preventing the Arabs from siding with Hitler’s Germany. With the war’s end in sight, Egypt and Saudi Arabia, then the region’s only independent countries, joined with four other Arab lands to raise the banner of the League of Arab States, a new association dedicated to ending European rule.

The Arabs’ sense of common cause was jolted to a new level of intensity in 1947, when the United Nations approved the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine. The ensuing war over its creation led to what Arabs call the naqba, or disaster, meaning the loss of Arab lands to the Israelis and the flight of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians to neighboring Arab states. The struggle against Israel replaced the anticolonial effort as the Arabs’ defining mission, keeping them bonded together like no other peoples. Starting with the first Arab-Israeli war, in 1948, their failure to obtain a state for the Palestinians has also kept alive a sense of shared guilt and injustice at the hands of the West.

During the Mubarak years, other voices and centers have arisen, particularly on the western shores of the Persian Gulf. There, monarchies once thought quaint relics of Arab history—including Qatar, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates—have taken on new life. The accumulation of massive oil wealth in the hands of kings and emirs amid soaring demand and prices over the past few decades has given birth to a far more diverse and multipolar Arab world.

There were moments of great hope for Arab unity, illusory as it proved to be. Riding to power in an army coup in 1952, Nasser quickly became the undisputed Saut el-Arab, or Voice of the Arabs, his views broadcast far and wide through a powerful Cairo-based radio station of the same name. With his rabble-rousing speeches, Nasser offered a vision of an Arab world transformed from a colonial jigsaw puzzle of artificially defined states into one big umma, a single Muslim community stretching from Morocco on the Atlantic to Oman at the mouth of the Persian Gulf.

Nasser preached pan-Arabism and Arab nationalism to rally the masses against the two Cold War superpowers and Israel. Initially, his record was impressive. He electrified the Arab world in 1956 by boldly nationalizing the Suez Canal, then in the hands of a British-run company. And, with indispensable backing from President Dwight D. Eisenhower, he faced down France, Britain, and Israel when they invaded to take back the canal. Nasser also took the first step toward formal Arab unity by convincing Syria two years later to join Egypt in a “United Arab Republic” (though the union was short-lived). And with consummate diplomatic cunning, he succeeded in catapulting Egypt to the head of the Non-Aligned Movement, whose members sought to maintain their independence from the two Cold War blocs, and deftly extracted billions of dollars in arms from the Soviet Union and $800 million in wheat and other foodstuffs from the United States.

Nasser’s star dimmed considerably, however, after his army’s crushing defeat by Israel in the 1967 Six-Day War, a disaster that led him to dramatically offer his resignation to the Egyptian people. The war ended with Israel in possession of Egypt’s vast Sinai Desert as well as Syria’s Golan Heights and Jordan’s West Bank and East Jerusalem. Weeping Cairenes nonetheless poured into the streets to insist that Nasser remain their leader. But the grand old Voice of the Arabs never recovered his prestige before a heart attack killed him in 1970.

Sadat emerged from Nasser’s shadow offering a different style of leadership, one equally bold and imaginative though far more contested by other Arab capitals. He scuttled Nasser’s socialism by launching the infitah, an “open-door” policy aimed at liberalizing the economy, and he forged a new political order by ending single-party rule and allowing new parties to form. He survived an Israeli counterattack in the 1973 Yom Kippur War that nearly wiped out his army, and then decided on his own to make peace with Israel, regaining the Sinai for Egypt. After his iconoclastic trip to Jerusalem in 1977, Sadat pushed through a bilateral peace agreement with Israel that took effect two years later, provoking the Arab League (as the League of Arab States was now known) to oust Egypt, effectively ending its leadership of the Arab world. But Sadat stood firm. As events would prove, even his assassination at the hands of Islamist militants who were vehemently opposed to peace with Israel could not reverse his feat. Sadat had single-handedly changed the course of Middle East history.

Since Sadat’s demise, the Arab world has struggled to find its ideological bearings. The old secular leftist ideologies of Arab nationalism, Arab socialism, and pan-Arabism are rarely mentioned anymore. Their last two standard-bearers, Hafez al-Assad of Syria and Saddam Hussein of Iraq, proved unequal to the task of leading the Arab world and were discredited, along with the “isms” they represented. Assad, who ruled for 29 years, was able to extend his influence no farther than neighboring Lebanon. Hussein came to power in 1979 and was an international pariah after 1990, when he invaded Kuwait, a brother Arab country.

Time has made a mockery of Arab aspirations to unity as well. The 21 countries of the Arab League (plus the Palestinians), embracing 350 million people, have come to live in a state of endless squabbling and continuing fragmentation. Even smaller wannabe regional blocs, such as the six Arab monarchies of the Gulf Cooperation Council (Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, and Oman) and the four Mediterranean countries of the Maghreb (Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria, and Libya), have made precious little headway toward unity.

Instead, the Arab world has been plagued by civil wars (Sudan, Lebanon, and Somalia), militant Islamist insurgencies (Algeria, Iraq, and Somalia), and sectarian strife between Sunni and Shiite Muslims (Iraq, Lebanon, and Bahrain), as well as an intramural struggle for the hearts and minds of Sunni Arabs pitting extremists against mainstream elements over the very meaning of Islam (Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Algeria). Terrorism, embodied by Al Qaeda, has become a scourge, survival a 24/7 preoccupation.

Central to the region’s turmoil is the widening rift between Sunnis, who account for nearly 90 percent of the Arab population, and Shia, who form tiny minorities in most Arab countries but constitute a majority in Iraq and Bahrain and probably a near majority in Lebanon. The Sunni-Shia conflict is almost as old as Islam, rooted in unforgotten bloody battles over who was the rightful heir of the Prophet Muhammad. It was given new life by the Iranian revolution of 1979, which produced a Shiite theocracy determined to expand the political and religious influence of this non-Arab power deep into the Sunni-dominated Arab world. More recently, Iran’s efforts to develop a nuclear capacity, perhaps including nuclear weapons, has further heightened tensions. Leaders of the Arab countries—most of whom are Sunni, with the notable exception of Iraq’s prime minister, Nuri al-Malaki, a Shia—are acutely aware that Iran is both Shiite and Persian.

Since Sadat’s demise, the Arab world has struggled to find its ideological bearings. The old secular leftist ideologies of Arab nationalism, Arab socialism, and pan-Arabism are rarely mentioned anymore. Their last two standard-bearers, Hafez al-Assad of Syria and Saddam Hussein of Iraq, proved unequal to the task of leading the Arab world and were discredited, along with the “isms” they represented.

The challenge from Iran helped stoke Sunni fundamentalism and put Islam front and center in the political discourse and daily lives of Arabs. And 1979, the year that saw the birth of theocracy in Iran, also brought the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the rise of an anti-Soviet jihad that intensified and spread the new religious fervor across the Arab world. Thousands of Arab would-be holy warriors signed up for the anticommunist cause in Afghanistan, then returned home to revolt against corrupt and repressive rule in their own countries. Islamic political parties preaching a return to the letter of the Qur’an and sharia law have now surpassed secular parties as the most dynamic forces in Arab political life. Mosques have become cauldrons of political activism. Preachers such as Yusuf al-Qaradawi, the fiery Egyptian Sunni cleric who broadcasts from Qatar, and Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, Iraq’s supreme Shiite authority, exercise far more sway than any politician. In Egypt, the fundamentalist Muslim Brotherhood has taken over as the main opposition political party, and other like-minded Islamist groups now occupy a central role in the politics of many Arab states.

The U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 also played a major role in keeping Islamic militancy alive and well and sharpening Sunni-Shiite animosities. The overthrow of Saddam Hussein meant an end to Sunni rule in Iraq as the Bush administration, in the name of democracy, ushered the Shia into power for the first time in the country’s contemporary history. By the thousands, Iraqi Sunnis joined an insurgency against the new government, while others found their way to Al Qaeda, which deliberately sought to incite a Sunni-Shiite confrontation by bombing Shiite neighborhoods and holy sites.

The tidal wave of political Islam has rocked the Arab world’s mostly autocratic rulers, sweeping away any reform impulses they may have had and leaving them concerned almost exclusively with their own day-to-day survival. To these leaders, most ideas for change or reform now look like foolish high-risk gambits, all the more so since some of the prime promoters of change have been Western outsiders. The resulting stasis has contributed to a remarkable lack of turnover in leadership. In his 29-year reign, Mubarak has employed an increasingly unpopular state of emergency to crush his opponents and extinguish hopes for multiparty democracy in Egypt. Muammar al-Qaddafi, until recently an international outcast because of Libya’s terrorist activities, celebrated the 40th year of his reign last September. Sudanese president Omer Hassan Ahmed Al Bashir, wanted on war crimes charges by the International Criminal Court, came to power 20 years ago. In Oman, Qaboos bin Said deposed his father in 1970 and has remained sultan ever since. Ali Abdullah Saleh has been the leader of Yemen for 31 years, and Zine el-Abidinia Ben Ali has led Tunisia for 22.

The staying power of these autocrats pales next to the longevity of the royal houses of the Persian Gulf. The ruling families of Qatar, Kuwait, and Bahrain have reigned for centuries, including a long spell under “protectorates” imposed by the British. The Saudi royal family, in a land that escaped colonial domination, has ruled on and off for more than 250 years. But the record for Arab longevity lies in a land far beyond the gulf, in Morocco, where Mohammed VI reigns as the 18th king in a dynasty that came to power in 1666.

Secular Arab leaders have been working hard to establish their own family dynasties. As he had arranged, Hafez al-Assad of Syria was succeeded upon his death in 2000 by his 35-year-old son, Bashar, a British-trained ophthalmologist who had previously shown little interest in politics. Both Mubarak and Qaddafi have been grooming their sons to take over from them, as has President Saleh in Yemen.

Surveying the Arab world in the troubled aftermath of the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq, President George W. Bush saw the dead hand of autocracy as a key cause of the Arab world’s stagnation, and he even conceded that the United States had helped keep Mubarak and other Arab autocrats in power. Bush proposed a radical cure. His “forward strategy of freedom” would bring democracy to the Arabs.“As long as the Middle East remains a place where freedom does not flourish,” he declared in 2003, “it will remain a place of stagnation, resentment, and violence ready for export.” No longer would the United States accept the Arab status quo. Bush called specifically on America’s chief Arab allies, Egypt and Saudi Arabia, to “show the way toward democracy in the Middle East.”

The tidal wave of political Islam has rocked the Arab world’s mostly autocratic rulers, sweeping away any reform impulses they may have had and leaving them concerned almost exclusively with their own day-to-day survival. To these leaders, most ideas for change or reform now look like foolish high-risk gambits, all the more so since some of the prime promoters of change have been Western outsiders. The resulting stasis has contributed to a remarkable lack of turnover in leadership.

Mubarak and Abdullah (still crown prince at the time) denounced the American diktat, insisting that each country must determine its own path to reform. Yet Arab leaders did respond to Bush’s call, and they proved master manipulators of democracy. They held elections, loosened press censorship, and allowed a bit more space for dissident voices on the Internet. And they quickly learned how to diffuse, divide, and checkmate even this feeble opposition.

Mubarak simultaneously rigged election laws to make himself president for life and allowed the birth of a semifree opposition press. Algerian president Abdelaziz Bouteflika permitted many political parties and 76 independent national daily newspapers to flourish even as he altered the constitution to perpetuate his rule. Qatar’s al-Thani ruling family dropped plans for an elected parliament but launched the al-Jazeera satellite television channel, which has revolutionized Arab news coverage with its critical reports, lively debates, and airing of the radical views of Islamists as well as secular oppositionists.

Arab leaders skillfully used elections to illustrate the dangers democracy might end up posing to U.S. interests—exactly contrary to what President Bush had predicted. Saudi Arabia held municipal elections in early 2005, and Egypt elected a new parliament late that same year. The results: The most conservative, anti-Western Wahhabi candidates swept the Saudi contests, and the fundamentalist Muslim Brotherhood became the main opposition group in the Egyptian parliament. Finally, after the militantly anti-Israeli Hamas won a large majority in the 2006 elections for a new Palestinian parliament, Bush quietly shelved his “freedom agenda.” So far, President Barack Obama has carefully avoided making democracy promotion a signature cause of his administration. Indeed, he has been vigorously chastised by human rights advocates, Republican and Democrat alike, for abandoning the U.S. mission to spread democracy in the Arab world.

The experience of the past few years has left a bad taste in the mouths of many of democracy’s most fervent Arab supporters. After Bouteflika won a third five-year term in 2009, Algerian news commentator Mahmoud Belhimer opined that the electoral process there and elsewhere in the Arab world served “merely to perpetuate the permanent monopoly of the ruling elite on power, thus denying the vast majority of society the right to participation in public affairs.”

To further cement their monopoly, Arab leaders have seized upon the threat of Al Qaeda terrorism to promote their civilian and military intelligence services—the mukhabarat—to the forefront of political life. The heads of these agencies have become so powerful that they often play the role of kingmaker, or simply become candidates for the top job themselves. After fighting an Islamist insurgency throughout the 1990s, the intelligence service in Algeria is now the mainstay of the regime and the decisive factor in choosing presidents. In Saudi Arabia, the domestic civilian security chief, Minister of the Interior Nayef bin Abdulaziz, has emerged as a possible successor to King Abdullah after leading a successful crackdown on Al Qaeda terrorists. Mubarak has made his ubiquitous mukhabarat, with its two million agents and its jails filled with Islamist and secular dissidents, the backbone of his regime as well. The head of the Egyptian General Intelligence Services, Omar Suleiman, has become the leading candidate to succeed Mubarak should his son Gamal falter.

The argument that a “freedom deficit” lies at the core of the Arab world’s woes was not invented by President Bush. It was earlier advanced by a group of independent Arab scholars who in 2002 began producing a regular series, the Arab Human Development Reports, for the United Nations. “The wave of democracy that transformed governance in most of Latin America and East Asia in the 1980s and Eastern Europe and much of Central Asia in the late 1980s and early 1990s has barely reached the Arab states,” they wrote.

The group has systematically probed the causes of the Arab failure to keep up with the rest of the world in areas ranging from education to the advancement of women. Sixty-five million Arab adults, mainly women, remain illiterate; less than 1 percent of Arab adults use the Internet, and only 1.2 percent have computers. No Arab university has any standing in world rankings. Arab regimes’ miserable failure to meet the challenges of globalization has led to high rates of unemployment and poverty. In 2002, one in every five Arabs was living on less than $2 a day. The report blamed the Arab world’s stagnating economies, particularly in non–oil-producing countries, on many leaders’ fixation with “discredited statist, inward-looking development models.”

In 2008, the average unemployment rate still stood at a disturbing 15 percent in North Africa and 12 percent in the rest of the Arab world, according to the International Labor Organization. Among the young it was higher—17 percent in Egypt and 25 percent in Algeria. In these and other Arab states, high food prices, poor housing, and a lack of jobs constantly threaten to ignite social explosions and give Islamist groups a popular cause to ride.

In Egypt, the specter of bread riots haunts the political elite decades after Sadat’s attempt to cut subsidies in 1977 sparked nationwide street protests and forced him to call out the army. Eight hundred people died in the ensuing clashes, and Islamic militants took advantage of the disorder to sack dozens of alcohol-serving nightclubs along the tourist route to Cairo’s pyramids. Sadat quickly reversed himself.

Selling for the equivalent of a penny, the flat, round baladi breadis the staple of poor Egyptians and literally keeps the social peace. In March 2008, when there was a sudden shortage of bread, an anxious Mubarak called upon the army to use its own flour supplies to bake baladis. But Egyptians forced to stand in endless lines clashed with police, and both the Muslim Brotherhood and secular opposition parties took to the streets to show their solidarity and denounce the government.

Algeria harbors an even greater potential for social unrest and Islamic agitation. Because of their long and successful liberation struggle against France (1954–62), Algerians are more likely than most Arabs to believe in revolts and demonstrations as means of changing the status quo. Riots in Algiers over bad living conditions nearly brought down the military government in 1988 after the outburst grew into a national protest movement that Islamic militants were able to take over. The military then fought a bloody, dirty war against disaffected Islamists throughout the 1990s. It has remained ever since in fear of another Islamist uprising. Last January, security forces rushed to halt a march by tens of thousands of Islamists from the suburbs into downtown Algiers. The crowds had taken to the streets to show their solidarity with the radical Palestinian faction, Hamas, then battling Israeli forces that had invaded its stronghold in the Gaza Strip.

This nervousness about the Arab Street prevails in virtually every capital in the Arab world—except, surprisingly, among the Persian Gulf monarchies, regimes one might expect to be the most worried. But the monarchies are blessed with small populations and enormous wealth. Their special circumstances call into doubt whether they can serve as a model for the rest of the Arab world. But this is what they are aspiring to do, starting with a renovation of their backward education systems.

In 2008, the average unemployment rate still stood at a disturbing 15 percent in North Africa and 12 percent in the rest of the Arab world, according to the International Labor Organization. Among the young it was higher—17 percent in Egypt and 25 percent in Algeria. In these and other Arab states, high food prices, poor housing, and a lack of jobs constantly threaten to ignite social explosions and give Islamist groups a popular cause to ride.

The gulf states have begun pouring billions of dollars into new universities and inviting American and other Western universities to set up local branches. There are new American-run or -supported institutions in Kuwait (two), Qatar (three), Oman (three), Bahrain (one), and the United Arab Emirates (nine). In Qatar, the government has set aside land in the capital, Doha, to build an entire “Education City” to attract foreign universities.

Last September, the first 400 students, including 20 Saudi women, arrived at Saudi Arabia’s King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), a state-of-the-art coeducational graduate research institute endowed with $10 billion from the king’s personal coffers. Located along the Red Sea shore 50 miles north of Jidda, KAUST represents a bold gamble by Abdullah to promote social change over the heated objections of his own backward-looking Wahhabi clerical establishment. Taboos of Saudi society have been thrown out the window: Women not only take classes together with men, they are allowed to drive on the campus and do not have to veil their faces. One senior cleric roundly denounced such practices as “a great sin and a great evil.” Abdullah responded by firing him from the kingdom’s highest religious council, after making clear his intent to have KAUST serve as a “beacon of tolerance” for all Saudi society.

Saudi Arabia is the one new Arab powerhouse to have emerged as a player on the international scene. Its status as the world’s central oil bank—it has the largest reserves (267 billion barrels) and production capacity (12.5 million barrels a day)—and holder of massive dollar reserves ($395 billion in mid-2009) puts it in a unique position among the Arab states. The kingdom is the only Arab country in the Group of 20, the organization of the world’s major economic powers. In that role, to the displeasure of some other oil-producing nations, it has so far remained a firm supporter of the dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency.

In many ways, the Saudi king stands out as a notable exception to the criticism that old age and longevity in power have ossified Arab leadership. Now 86, Abdullah has proven unexpectedly energetic and innovative. As crown prince in 2003, he launched a formal “National Dialogue” that forced leaders of the feuding Sunni, Shiite, and smaller Muslim sects to discuss their differences. He then convoked Saudis from all walks of life to discuss hot-button social and religious issues. After taking the throne in 2005, Abdullah fired some of the most reactionary clerics running the religious establishment, sidelined others in the government, and promoted reformers to replace them. He has also cracked down on the excesses of the Taliban-like Wahhabi religious police, and launched a nationwide campaign to reeducate Wahhabi clerics away from extremism.

Conscious that his country’s reputation was damaged by the fact that 15 of the 19 hijackers of 9/11 were Saudi citizens, Abdullah has reached out to the West. In 2008, he addressed a Saudi-promoted “culture of peace” conference at the UN General Assembly, the first time in half a century a Saudi king had appeared before the world body.

More remarkably, Abdullah engineered the boldest Arab initiative to resolve the Palestinian-Israeli deadlock since Sadat flew to Jerusalem. In retrospect, it seems something of a miracle that he succeeded in getting the entire 22-member Arab League to adopt his initiative at its Beirut summit in 2002. The plan offered peace, security guarantees, and normalization of relations with Israel in return for an Israeli withdrawal from Arab territories occupied in the 1967 war. Not so long ago, Arab leaders would have objected to even an implicit recognition of Israel. Unfortunately, Abdullah’s initiative elicited no response from either Tel Aviv or Washington.

For all his efforts, Abdullah has not been able to rally the Arab Street or, apart from the Beirut summit, other Arab leaders. Saudi financial largesse has lost its purchasing power in other Arab capitals, and Saudi diplomacy now has limits even in the kingdom’s backyard on the Arabian Peninsula. The spread of massive oil wealth since the sharp increase in global oil prices began in the late 1990s has made it possible for even the tiny emirates to defy the mighty Saudi kingdom.

The limits of Saudi influence became painfully apparent when the Saudis, alarmed by the rise of a Shia-led government in Baghdad after the fall of Saddam Hussein, joined with Egypt and Jordan in an effort to rally other Sunni Arab leaders against the spread of Iranian influence. By then, Tehran had already made inroads into Lebanon by supporting the Shiite faction, Hezbollah, and into Palestinian politics by backing Hamas. Jordan’s King Abdullah warned of an emerging “Shiite crescent” stretching from Iran to Lebanon and the Palestinian territories. In Egypt, authorities uncovered a network of secret Hezbollah cells, and last year in Yemen the government accused the Iranians of fomenting rebellion among members of a local Shiite sect.

But the anti-Iranian campaign served more to divide than to unite the Arab world. Last January, after Israeli troops invaded the Gaza Strip in a bid to destroy Hamas, Qatar defied Saudi Arabia’s king Abdullah and President Mubarak by calling for an emergency Arab summit to show support for the radical Iranian-backed group. Fourteen of the Arab League’s members sent representatives, while Saudi Arabia and Egypt, the league’s wealthiest and most populous members, respectively, could only join others in a boycott.

The powerhouse of the Arabian Peninsula cannot impose its will even on its tiny neighbors in the Gulf Cooperation Council. The GCC brought together six monarchies—kingdoms, emirates, and a sultanate—in 1981 to deal with the challenge from Iran’s militant Shiite clerics, who were bent on exporting their revolution across the Persian Gulf. It established a collective defense force in 1986 under Saudi command, but the so-called Peninsula Shield never amounted to more than a nucleus of at most 9,000 soldiers. Pentagon efforts over the years to encourage GCC members to integrate their air, land, and sea defenses have had limited results.

Why this failure of collective self-defense even among a subgroup of similar Arab countries confronted by a common threat? One constant of GCC politics is fear of Saudi hegemony. The United Arab Emirates and Qatar both have had territorial feuds with the Saudis, and there have been numerous economic squabbles. When Bahrain infuriated the Saudis by signing a bilateral free-trade agreement with the United States in 2004, for example, the kingdom retaliated by temporarily cutting off Bahrain’s portion of the output from an oil field they share.

Nowhere are GCC members’ differences more on display than in their attitudes toward Iran. For Saudi Arabia, the Shiite theocracy looms as the main challenger to its religious and political influence in the Sunni Arab world. The prospect of a nuclear-armed Iran has alarmed the Saudis because of their fears that Tehran would be able to bully its Arab neighbors. The kingdom has been the most disposed of all the GCC members to support tougher economic sanctions, possibly even U.S. military action, to stop Iran’s drive to join the world’s nuclear club.

Qatar, on the other hand, has maintained an open-door policy and even at times aligned itself with Tehran against Riyadh—influenced in part by the fact that it jointly exploits a huge offshore gas field with Iran. To great Saudi displeasure, the Qataris invited Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad to attend the 2007 GCC annual summit, a first for any Iranian leader. Qatar has also sided with Iran’s militant friends in the Arab world, namely Hezbollah and Hamas; it even took over floundering Saudi efforts to mediate among Lebanese factions in 2008 in brokering an accord that gave Hezbollah a decisive voice in forming a new government, succeeding in Beirut.

Oman has also gone out of its way to remain on good terms with Tehran, partly because the two countries face each other across the Strait of Hormuz, the passageway for all oil tankers leaving the Persian Gulf. So has the United Arab Emirates, a constellation of seven semiautonomous city-states. The largest emirate, Dubai, is the main transshipment point for Iranian exports and imports, still often ferried across the gulf in old-fashioned wooden dhows. This flourishing trade continues unabated despite UN economic sanctions on Iran, not to mention Iran’s continuing military occupation of three islands claimed by the emirates.

How has it been possible for these statelets to forge such independent foreign policies? The answer lies in their massive oil and gas wealth. For example, Qatar, with an indigenous population of less than 200,000, boasts the world’s third-largest natural gas reserves, after Russia and Iran, and is the world’s largest exporter of liquefied natural gas. It had a gross domestic product of $106 billion in 2008. Egypt, with its 80 million people, had a GDP of only $158 billion. Even counting Qatar’s foreign resident population of slightly more than one million, its per capita income of $93,204 was twice that of the United States in 2008, ranking second worldwide.

The case of the United Arab Emirates is just as striking. With an indigenous population of 1.3 million (out of a total population of 4.3 million), it had a GDP of $270 billion in 2008, more than half that of Saudi Arabia, which has 20 times as many nationals. Its sovereign investment fund—the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority—was the world’s largest in 2008, with assets of $627 billion. Kuwait, Bahrain, and Oman had similarly outsized economies.

Fabulous wealth has made it possible for the gulf ministates to do more than just dream impossible dreams. The rulers of Dubai, Abu Dhabi, and Qatar have invested hundreds of billions of dollars in glitzy new “global cities” that aspire to become centers for play, business, and finance appealing to Arabs and non-Arabs alike. They host UN conferences and celebrity-studded events that trumpet their high hopes. The Doha Tribeca Film Festival in Qatar boasts Robert DeNiro among its marquee names. Abu Dhabi’s plans include both a

“Louvre Abu Dhabi” and a Guggenheim museum designed by world-renowned architect Frank Gehry.

There is an air of unreality about these would-be global cities. Doha’s skyline is dotted with cranes, and its downtown is an unending series of construction sites and twisting highway detours. Pakistanis, Indians, Sri Lankans, Nepalese, Filipinos, and Egyptians have come by the hundreds of thousands to build a new shining city on the sands around a barren bay. The quaint old quarters at the city’s heart are surrounded by towering hotels and conference centers. Native Qataris seem a vanishing species. A visitor could easily pass a week in Doha rarely meeting a Qatari or hearing Arabic spoken.

How has it been possible for these statelets to forge such independent foreign policies? The answer lies in their massive oil and gas wealth. For example, Qatar, with an indigenous population of less than 200,000, boasts the world’s third-largest natural gas reserves, after Russia and Iran, and is the world’s largest exporter of liquefied natural gas. It had a gross domestic product of $106 billion in 2008.

Even before Dubai essentially defaulted on $60 billion in debt last November, the world financial crisis of 2008–09 had brought a halt, or at least a pause, to the great Dubai dream of a new global city. Scores of projects were put on hold and tens of thousands of foreign workers sent home. Oman, too, was hard hit. But the other gulf statelets simply dug deeper into their foreign reserves to ride out the downturn, while Saudi Arabia, with $400 billion in its pocket, hardly skipped a beat.

If tiny Qatar can defy giant Saudi Arabia, what is the likelihood that the Arab world will ever produce another charismatic zaim of the stature of Nasser or Sadat, or that Egypt will re-emerge as its political dynamo? The chances appear exceedingly slim. Egypt may still have some of the key ingredients for leadership—the mightiest army, the biggest population, and the most central geographic location. But it remains resource poor and heavily dependent on unreliable revenues from abroad—multibillion-dollar grants from the United States, European and Arab tourism, and remittances from the two million Egyptians who work in other countries.

Not only has the center of Arab wealth moved to the gulf; so, too, has the source of new initiatives and thinking. Visiting Cairo last April, a New York Times reporter found its chattering classes demoralized and despairing. A leading television writer, Osama Anwar Okasha, lamented that Egypt had become “a third-class country.” It is “not influential in anything,” he grumbled. Cairo has lost even its role as the soap opera capital of the Arab world, its state-sponsored offerings trounced in the ratings during the critical Ramadan month of fasting by livelier confections such as Turkey’s Noor, which follows the heart-rending story of a young couple forced into a traditional family-arranged marriage. Egyptians were embarrassed last year by Mubarak’s effort to promote culture minister Farouk Hosny, widely seen as Cairo’s Savonarola, as UNESCO’s new director-general. Hosny blamed the failure of his candidacy on a Jewish conspiracy “cooked up in New York.” As if this were not enough, Egyptians suffered another blow to their self esteem last November when Algeria eliminated their soccer team from World Cup contention. In the ensuing dustup, both countries recalled their ambassadors.

The decline of Egypt has been an especially bitter pill for the country’s best and brightest to swallow. The literate are divided over whether the blame lies chiefly with the peace treaty with Israel, which deprived Egypt of a military option and thus weakened its diplomacy with Tel Aviv, or with Mubarak. The Egyptian president himself seems to have supplied the answer, allowing King Abdullah to eclipse him with his 2002 peace initiative and failing in his effort to mediate among feuding Palestinian factions.

Mubarak’s son and possible successor Gamal has deftly promoted his image at home and abroad as a reform-minded modernizer, but it seems unlikely that any leader will be able to restore Egypt to its role as umm idduniya. Some reformers’ hearts fluttered in December when Mohamed ElBaradei, who won a Nobel Prize as head of the International Atomic Energy Agency, declared his interest in running for Egypt’s presidency in 2011, but he attached conditions the government is unlikely to satisfy.

Washington regularly bemoans the lack of an “Arab partner” in the peace process, and presses Egypt in particular to do more. Abdullah’s success in pulling Arab rulers together behind a plan illustrates that strong leadership can serve to forge a single Arab voice on even the most divisive issues. But the single, clear voice of 2002 did little to help achieve a breakthrough in the Israeli-Palestinian deadlock; nor has Arab unanimity in backing a multitude of anti-Israel resolutions at the United Nations accomplished anything. And the Arab League’s unanimous support for Sudanese leader Omar al-Bashir, faced with war crime charges by the International Criminal Court, has not enhanced the Arab voice in world affairs.

It is no longer clear, either, what the Arab world stands to gain by an Egypt strutting back to center stage. There is no enticing “Egyptian model” for development—political or economic. New thinking, visions, and initiatives have come largely from the Persian Gulf states and their freewheeling, competitive rulers, while Egypt still seems encumbered by its Pharaonic nature from embarking on radical change. On the whole, the Arab world has gained in vitality in Egypt’s decline.

That world now stares at two sharply contrasting models of its future: the highly materialistic emirate state obsessed with visions of Western-style modernity, and the strict Islamic one fixed on resurrecting the Qur’an’s dictates espoused by fundamentalists and Al Qaeda. The struggle between these two models for the hearts and minds of Arabs is intense, particularly among a questioning, restless youth. The lure of the new, shiny emirate cities remains powerful, but there is a soulless quality about these places that raises questions about their lasting appeal. On the other hand, Muslim terrorism unleashed against other Muslims has done nothing to enhance the call for an Islamic state.

There are signs, perhaps false, that the appeal of militant Islam is waning. Support for Islamic parties has dropped in recent elections in Jordan, Kuwait, Morocco, and Algeria. But this may only reflect the growing disillusionment with government-rigged elections, as falling voter turnout strongly suggests. In fact, there is a fierce debate under way within the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt and like-minded Islamist groups elsewhere over whether they should continue to participate in the electoral process.

Analysts of the Arab world are all too aware that prediction is a fool’s game. As a journalist covering the region, I have reported more times than I can count the confident predictions after the shah fell in 1979 that the Arab monarchies were next. Today, those same regimes are not only alive and well but thriving. Militant Islam has not swept them away. Predicting the outcome of the continuing struggle between Arab autocrats, royal and secular, and their Islamist opponents seems equally perilous today. The Arab future is not limited to a choice between autocracy and theocracy. As both Turkey and Indonesia powerfully illustrate, there is nothing inherently contradictory between Islam and authentic multiparty democracy. These countries, too, were once ruled by autocrats, and they both have had to figure out the role of Islam in politics.

It is no longer clear, either, what the Arab world stands to gain by an Egypt strutting back to center stage. There is no enticing “Egyptian model” for development—political or economic. New thinking, visions, and initiatives have come largely from the Persian Gulf states and their freewheeling, competitive rulers, while Egypt still seems encumbered by its Pharaonic nature from embarking on radical change. On the whole, the Arab world has gained in vitality in Egypt’s decline.

Whoever comes to rule Egypt after Mubarak will walk upon an Arab landscape that has undergone change that is probably irreversible. Not only is the Arab world multipolar in wealth and influence; its eastern and western flanks are slowly being pulled in opposite directions by different global markets. Centrifugal economic forces are becoming more powerful than centripetal political ones. For the oil- and gas-exporting gulf states, the thriving economies of China, India, and other Asian nations have become a powerful magnet; for the Maghreb countries, the European Union plays that role. Saudi Arabia aspires to become the prime supplier of foreign oil to gas-guzzling China; Algeria is doubling the capacity to transport its Sahara gas by underwater pipelines to energy-starved Italy and Spain.

By and large, the economic prospects for most Arab countries appear reasonably hopeful. A majority have oil or gas, and even non–oil-producing countries such as Jordan and Morocco, and minor producers such as Tunisia, have fair to good prospects. Many were on the move economically before the latest world financial crisis, and they have not come to a halt because of it. Even war-devastated Iraq has struck deals with foreign firms to nearly triple its current production of 2.5 million barrels a day in the next six years.

By contrast, Arab political prospects are deeply troubling. Monarchs, once thought headed for history’s dustbin, are doing surprisingly well at the moment. Both royal and secular autocrats are holding their Islamist challengers at bay thanks to highly manipulative or repressive security services. However, this prevailing model of Arab autocracy, dependent on the mukhabarat and a fabricated popular vote, does not seem a recipe for lasting political stability. Indeed, the Arab political cauldron contains all the ingredients for explosions in the years ahead.

* * *

David B. Ottaway, a senior scholar at The Woodrow Wilson Center, worked for The Washington Post from 1971 to 2006, including four years in Cairo as the Post's chief Middle East correspondent. His most recent book is The King's Messenger: Prince Bandar bin Sultan and America's Tangled Relationship with Saudi Arabia (2008).

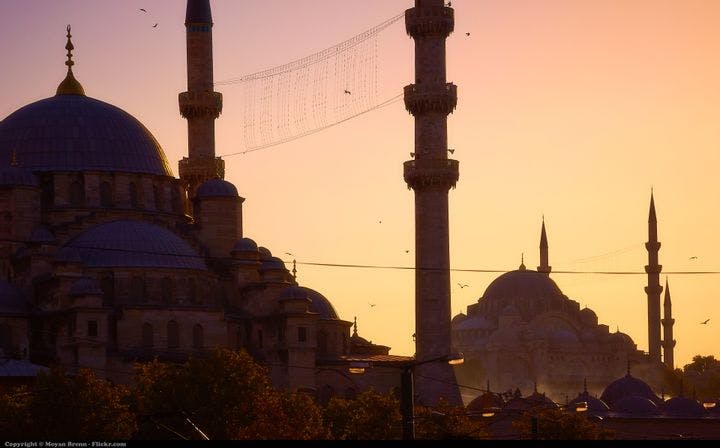

Photo courtesy of Flickr/Moyan Brenn