The Arctic, from Romance to Reality

– Michael Sfraga

From oil paintings and poetry to militarization and melting (and yes, even video games), our quest to understand the region at the top of the planet continues – and the stakes today are higher than ever.

“We were nearly surrounded by ice, which closed in the ship on all sides, scarcely leaving her the sea-room in which she floated. Our situation was somewhat dangerous, especially as we were encompassed round by a very thick fog.”

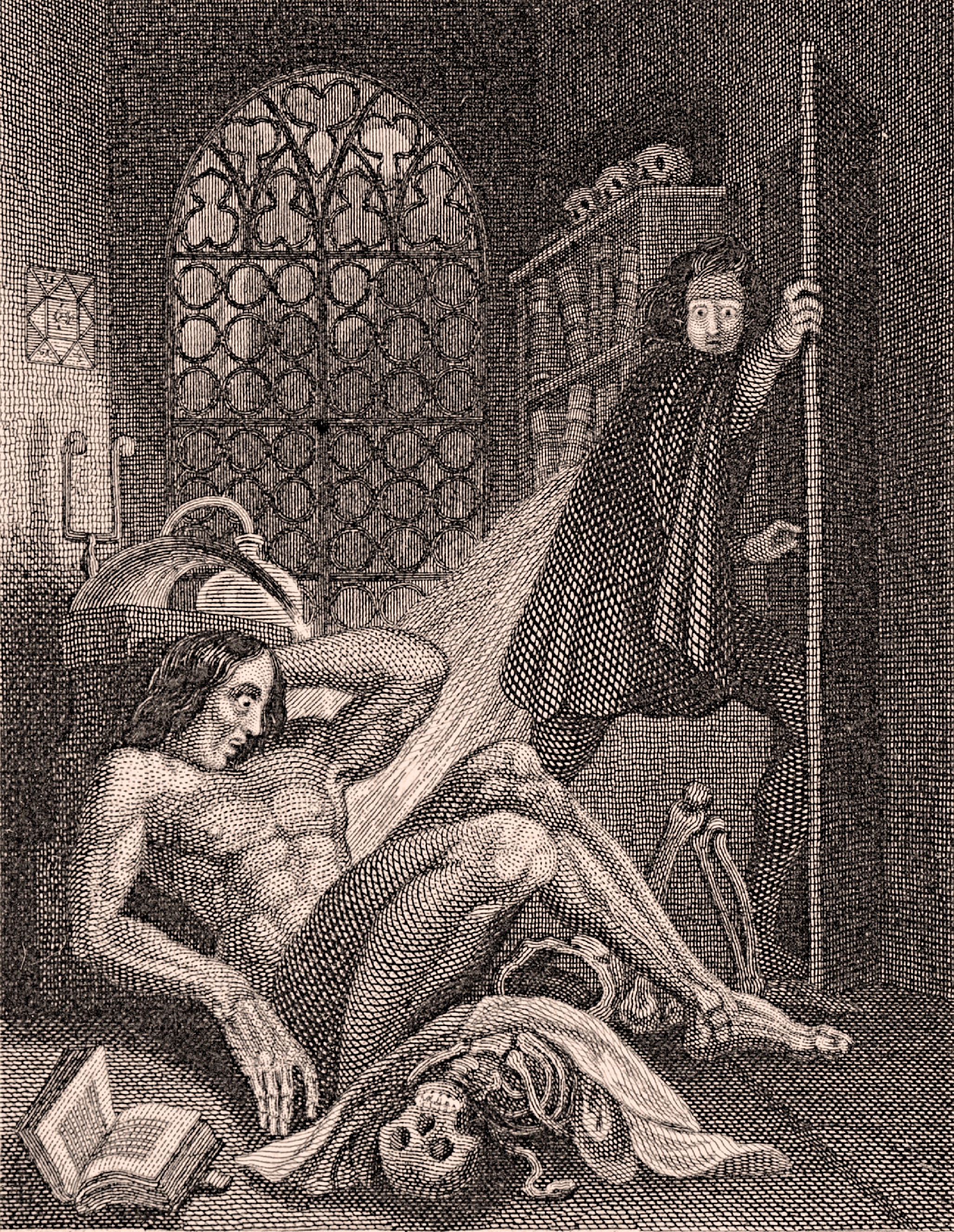

These are the observations of Mary Shelley’s fictional Arctic explorer Captain Robert Walton as he sails ever closer to the North Pole – spurred on by the promise of scientific discovery, geographic knowledge, and international acclaim.

“… The mist cleared away, and we beheld vast and irregular plains of ice, which seemed to have no end. Some of my comrades groaned, and my own mind began to grow watchful with anxious thoughts, when a strange sight suddenly attracted our attention, and diverted our solicitude from our own situation. We perceived a low carriage, fixed on a sledge and drawn by dogs, pass on towards the north, at the distance of half a mile: a being which had the shape of a man, but apparently of gigantic stature, sat in the sledge, and guided the dogs. We watched the rapid progress of the traveller with our telescopes, until he was lost among the distant inequalities of the ice.”

The being that Captain Walton spies, of course, is the Frankenstein monster. The setting Shelley chose for her 1818 masterpiece is indicative of the era’s fascination with the Arctic. It was the end of the Napoleonic Wars, which meant the availability of Britain’s vast and now relatively idle Navy, and there was an air of excitement at the chance of being the first nation to navigate the Northwest Passage and reach the North Pole. (Perhaps, as Walton hoped, and as many claimed, the North Pole would be surrounded by a tropical paradise). At this moment in time and in the decades immediately following Shelley’s work, artists of word and image fed public interest in the Arctic by depicting the sheer scale and scope of the North. Exploration narratives and oil paintings depicted immense icebergs, dwarfing both man and ship, or a distant, setting sun signaling the end of light and the onset of relentless cold and dark. This was a landscape at once terrifying and beautiful, at once treacherous and alluring, with the power and grandeur to overwhelm human comprehension. It also exemplified the notion of “the sublime” in Euro-American Romanticism. Buoyed by publicists and expedition-leaders, too, this Arctic sublime sent shivers down the public spine.

Voyages of Discovery

Less valued at the time, and, sadly, for generations to follow, were the rich cultures, languages, and lifestyles of those who had for thousands of years thrived in the landscape that seemed so uninhabitable to outsiders. The people who first called the Arctic home relied on intimate knowledge of the natural setting to carry out what was, for them, normal, unromanticized, day-to-day life. A number of explorers at the time did take back with them indigenous Arctic tools, clothing, and art – and, in some well-documented and disturbing cases, they even brought back the very individuals they encountered. Displaying such “curiosities” from afar served to stoke the imagination of those living in capital cities throughout Europe and the United States, but quickly turned proud cultures into a circus sideshow.

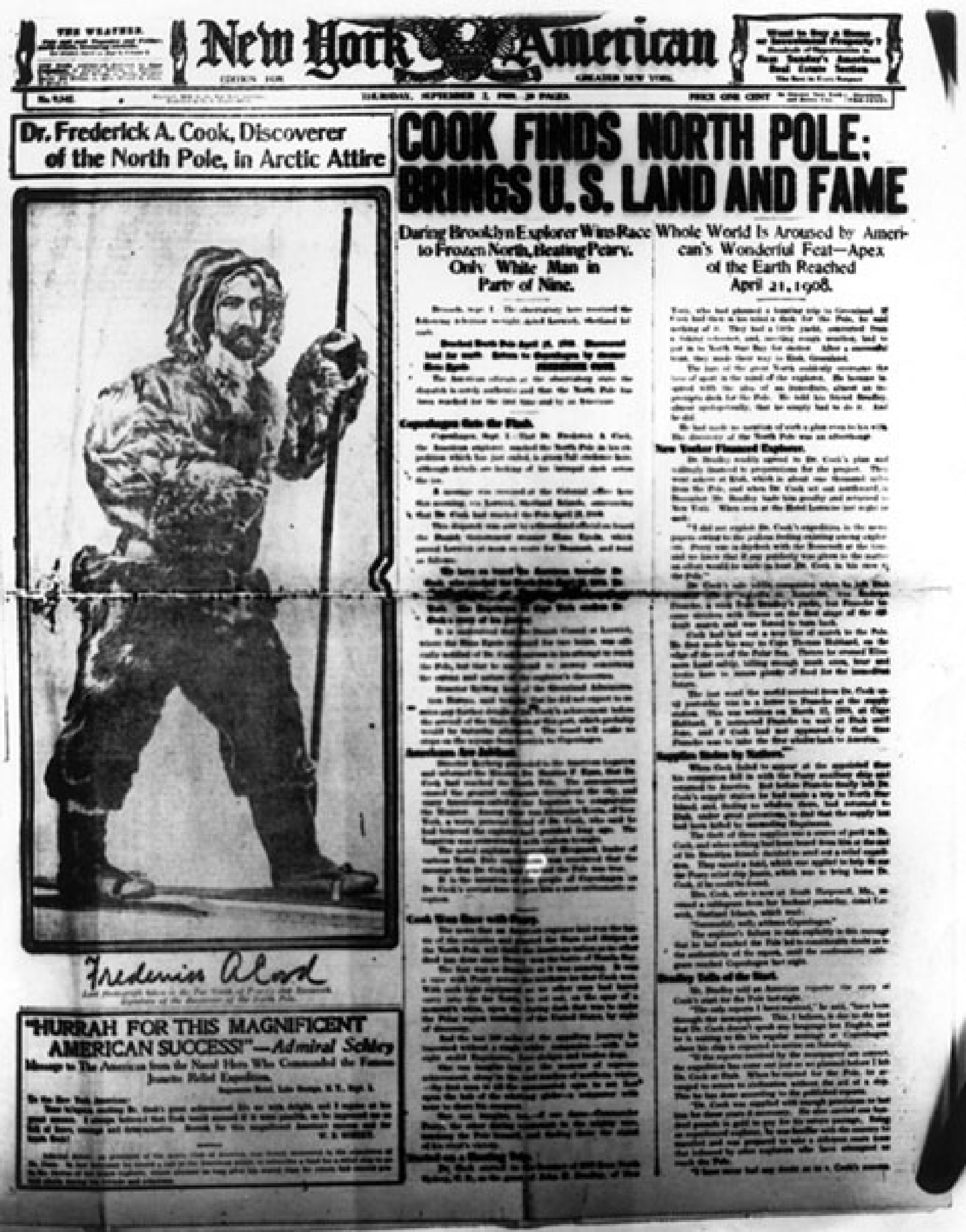

In the decades preceding the publication of Frankenstein, numerous expeditions had set out to discover the North Pole or the fabled routes connecting the Atlantic and Pacific through the Arctic, the Northeast and Northwest Passages. However, it wasn’t until later years that these ambitions were realized. In his voyage of 1878 to 1880, Baron Adolf Nordenskiold successfully sailed the Northeast Passage. Explorer Roald Amundsen traversed the Northwest Passage in his 1903-1906 expedition. Soon, Americans Dr. Frederic Cook (1908) and Admiral Robert Perry (1909) announced competing discoveries of the North Pole. Both of their claims are debated to this very day. Indeed, the history of early polar exploration is draped in lure and intrigue, fact and fiction.

Both the story of Frankenstein and the exploits of these northern explorers captivated me as a young boy. I remember sitting under the flickering street lamps on warm summer nights in Brooklyn to dive into the tall tales of Arctic adventure. The region was, literally and figuratively, a colder, more remote place than it is today. Much has changed in the Arctic since those summer nights in the 1960s, let alone since Captain Walton spied the famous monster darting through the frost.

Navigating Change

Today, the Arctic landscape is not just dramatic, but dramatically transforming. Temperatures are increasing at alarming rates worldwide, but warming in the Arctic is happening twice as fast as the global average. According to a 2017 report by the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Program (AMAP), the extent and thickness of sea ice continue to decrease. If predictions become reality, the Arctic Ocean could be mostly ice-free during the summer months in as little as 20 years. The implications of this unprecedented change in the Arctic are far-reaching, with social, political, economic, and environmental impacts rippling not just through the region, but globally.

According to the AMAP report, “Economic analysis of the global costs of Arctic change estimated the cumulative cost at USD $7-90 trillion over the period 2010-2100.” Although these numbers are so large as to sound like game board assets or play money, they should be taken quite seriously. One only need consider the vast amount of coastal infrastructure that exists around the world to begin to understand the impacts of rising sea levels. From metropolises to villages, from Fort Lauderdale, Florida to Barrow, Alaska, the many implications of a warming planet are more and more palpable today for coastal communities. Sea ice, which once protected Arctic coastal communities from storms and erosion, no longer affords the same security. As a result, dozens of communities in Alaska, for example, are at risk, and some have decided to relocate further inland. Hundreds of millions of dollars, if not billions of dollars, are needed to move these and similar communities to more stable ground.

Who decides their fate? Who pays for the relocation? And how do communities deal with the very real social and cultural upheaval that comes from such a move, including changes in traditional hunting and fishing grounds?

Perhaps the most powerful representation of indigenous culture, history, and the challenges at hand today is not a treatise, a study, or an article, but a video game. The award-winning Never Alone is far more than entertainment. Rather, it is a window on the Inupiat people of Alaska, and it connects landscape to soul, adversity to opportunity, and fragility to hope. Climate change is real, rapid, and palpable in this world. Never Alone is truly effective because the stories – the very voice and pulse of the people of the region – are heard, felt, and shared. Indeed, the game was crafted, informed, and designed by native Alaskan elders and storytellers.

More and more people today are listening to the story of the Arctic, especially as they realize that the region is a barometer of the changes that are literally baked into the global system – and that’s even if greenhouse-gas emissions were capped at the level agreed upon within the Paris climate accord. Still, international cooperation and frameworks are key to slowing rising temperatures, developing mitigation and resiliency strategies, and diversifying energy regimes. Sound policy requires sound, reliable scientific data. To that end, a significant step toward focusing the international community on the Arctic was taken when the first White House Arctic Science Ministerial meeting was held in Washington in September 2016. Science ministers from 24 nations convened to discuss the state of Arctic research and develop a more coordinated approach to scientific efforts throughout the North.

Arctic Organizing

The eight Arctic nations – Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the United States – compose the Arctic Council, a consensus-driven organization that provides a forum for discussion, projects, activities, and, in a few cases, binding agreements. The Council, now two decades old, plays a critical role in facilitating regular interaction on the Arctic. It has functioned well in a political environment fraught with conflict elsewhere. During its ministerial meeting in Fairbanks earlier this year, the Council passed a binding agreement on enhancing international Arctic scientific cooperation. In 2018, the EU, Finland, and Germany will host the second Arctic Science Ministerial, a positive next step in addressing the need for enhanced cooperation and capacity. The meeting is a key opportunity to emphasize the importance of better data, integrated research agendas, and consistent monitoring strategies to inform national and international policy. Sustained leadership from the United States is also required. Mark Brzezinski, the former U.S. ambassador to Sweden and former executive director of the U.S. Arctic Executive Steering Committee, has noted, “Washington... must be involved in the dialogue on the future of the Arctic because we are an Arctic nation. Too few Americans know that. And that is to our disadvantage.”

The fast-moving change in the Arctic also means new opportunities. A rapidly warming Arctic Ocean and landscape is boosting shipping and tourism, enlarging access to the region’s vast stores of natural resources, and creating space for the development and application of new technologies. The Arctic Economic Council, just a few years old, represents business interests, advocates for sustainable development, and has quickly become a vital bridge between Arctic communities in need of basic infrastructure and jobs and investment opportunities. The need to make sense of the Arctic’s competing and complementary issues at the local, regional, sub-national, national, and international levels was also the context for the creation of the University of the Arctic (UArctic), a network of more than 160 universities and institutes either located in the North or with a stated interest in the north.

Washington & Moscow Up North

The ongoing globalization of the Arctic is also accompanied by new geopolitical considerations. Much has been made of Russia’s recent activities in the region and whether they are compatible with an Arctic that is defined by cooperation. The Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation (AZRF), as Moscow calls it, is an expansive, transcontinental landscape that covers over half of the Arctic’s nine million square miles. The region is of great importance to Russia and, increasingly, to its Arctic neighbors as well as countries far away. That’s due in large part to the enormous stores of natural wealth, including oil, gas, and minerals, found in the Russian Arctic, as well as the Northern Sea Route (NSR), a key waterway for domestic shipping and international commerce that stretches from Novaya Zemlya in the West to the Bering Strait in the East. The AZRF and NSR are considered central components of Russia’s future economic, political, and national security. Indeed, Russia explicitly states the need for a secure, reliable resource base from the region, which can only be realized through sustainable development – made possible through both domestic and foreign investment. With 20% of Russia’s GDP originating from its Arctic warehouse, it is no wonder the country has placed a premium on modernizing its Cold-War-era ports and shipping infrastructure. Whether this justifies the recent build-up in Russian military assets is more debatable.

Russia’s increase in its military presence throughout AZRF and along the NSR is a reality that has been interpreted in a number of ways. To be sure, the Arctic has been, to one degree or another, militarized since the Cold War, but what are Russia’s motives today? Some believe the Kremlin is adopting an offensive posture, signaling a militarization of the Arctic. They also note Russia’s claim to a vast tract of land beneath the North Pole, punctuated by a ceremonial flag-planting on the floor of the Arctic Ocean. Other observers say Russia is taking pragmatic steps in modernizing its military, projecting force over its sovereign territory, and protecting an economic lifeline. As Senator Lisa Murkowski of Alaska recently said, “What we see with Russia is that they have made investment in the Arctic a priority. And quite frankly, to this point in time, we have not seen that same commitment to that priority [from the United States].”Although close monitoring by Washington and others actors is both expected and prudent, a measured and engaged approach is likely the wisest path forward. In truth, perhaps the most cooperative arenas for U.S.-Russian relations in recent years have been the Arctic, through the Arctic Council and Arctic Coast Guard Forum, and high above Earth at the International Space Station.

Although Washington and Moscow have stark differences on a range of issues, the two nations can indeed cooperate to keep the Arctic a zone of peace, engagement, and constructive action. In June of this year, the Wilson Center’s Polar Initiative and the Arctic Circle co-sponsored a two-day event exploring this key bilateral relationship in the Arctic. Differences were noted and discussed, but so was the long history of Arctic cooperation and the need for continued dialogue between and among all Arctic nations. Finland’s ambassador to the U.S., Kirsti Kauppi, perhaps captured best the sentiments of both speakers and attendees: “In a sense, the cooperation in the Arctic is a peace dividend after the Cold War… We are very convinced that it must be possible to continue the cooperation… and that it is in the interest of everybody to continue the cooperation. It is good to note that the [current] international tensions have not affected the work in the Arctic Council.”

The composition of the Council is also a sure sign that interest in the Arctic goes far beyond two power-players – and that interest is growing. Along with its eight Arctic-nation members and six Arctic indigenous peoples’ organizations, thirteen non-Arctic nations have been granted observer status. These countries are active on many levels in the Arctic, including in research, education, shipping, and direct investment in resource-development. China is one such observer, and is paying increasing attention to the region in the context of “One Belt, One Road,” a sweeping vision for the development of a modern Silk Road that attempts to leverage China’s ever-growing economic and political clout. In June of this year, Beijing announced the coupling of this initiative with its “21st-Century Maritime Silk Road.” China plans to link infrastructure and trade from the South China Sea to the Indian Ocean and has overtly declared plans to link Europe and the Arctic Ocean. At the same time, China’s multi-billion-dollar investment in Russia’s massive Sabetta liquefied natural gas project on the Yamal Peninsula underscores its interest in, and need for, reliable Arctic oil and gas.

The Arctic Moment

Admiral Paul Zukunft, commandant of the U.S. Coast Guard, recently argued that now should be the Arctic moment: “We have an awakening at the national level – that we have got to pay attention to what’s happening in the Arctic... What is our strategic approach? Is it going to be the next military campaign, or is it going to [be] working among coast guards [and] looking at rising sea levels [and] northern migrations of fish stocks?” With few exceptions, the international research community, as well as local, regional, national, and global leaders, recognize the Arctic as a region of breathtaking dynamism.

Today, if one were to randomly throw a dart at a calendar, the odds are that there is an Arctic-related gathering taking place somewhere in the world on that day, whether it’s of scientists, policymakers, industry representatives, indigenous leaders, or military experts. It might even be a gathering of camera-toting tourists; at this very moment, the cruise ship Crystal Serenity is, for the second year in a row, navigating the Northwest Passage. (What would Roald Amundsen think of that?) Indeed, we are living through a key chapter in the Arctic story, one that is being shaped by politics, culture, business, and profound planetary change. Welcome to complex reality of the modern global Arctic.

* * *

Michael Sfraga is the director of the Wilson Center’s Polar Initiative and is an affiliate faculty member of the International Arctic Research Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. He serves as co-director of the University of the Arctic’s Institute for Arctic Policy and has served as co-lead scholar for the Fulbright Arctic Initiative since its inception.

Cover image of The Icebergs by Frederic Edwin Church, 1861 (courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)