Winter 2019

The Battlefield 22,000 Miles above Earth

– Christian Davenport

The U.S. military’s vital space assets are an Achilles heel in orbit that China and Russia are working to exploit. Whether or not a Space Force comes into being, the Pentagon is faced with a real and growing threat.

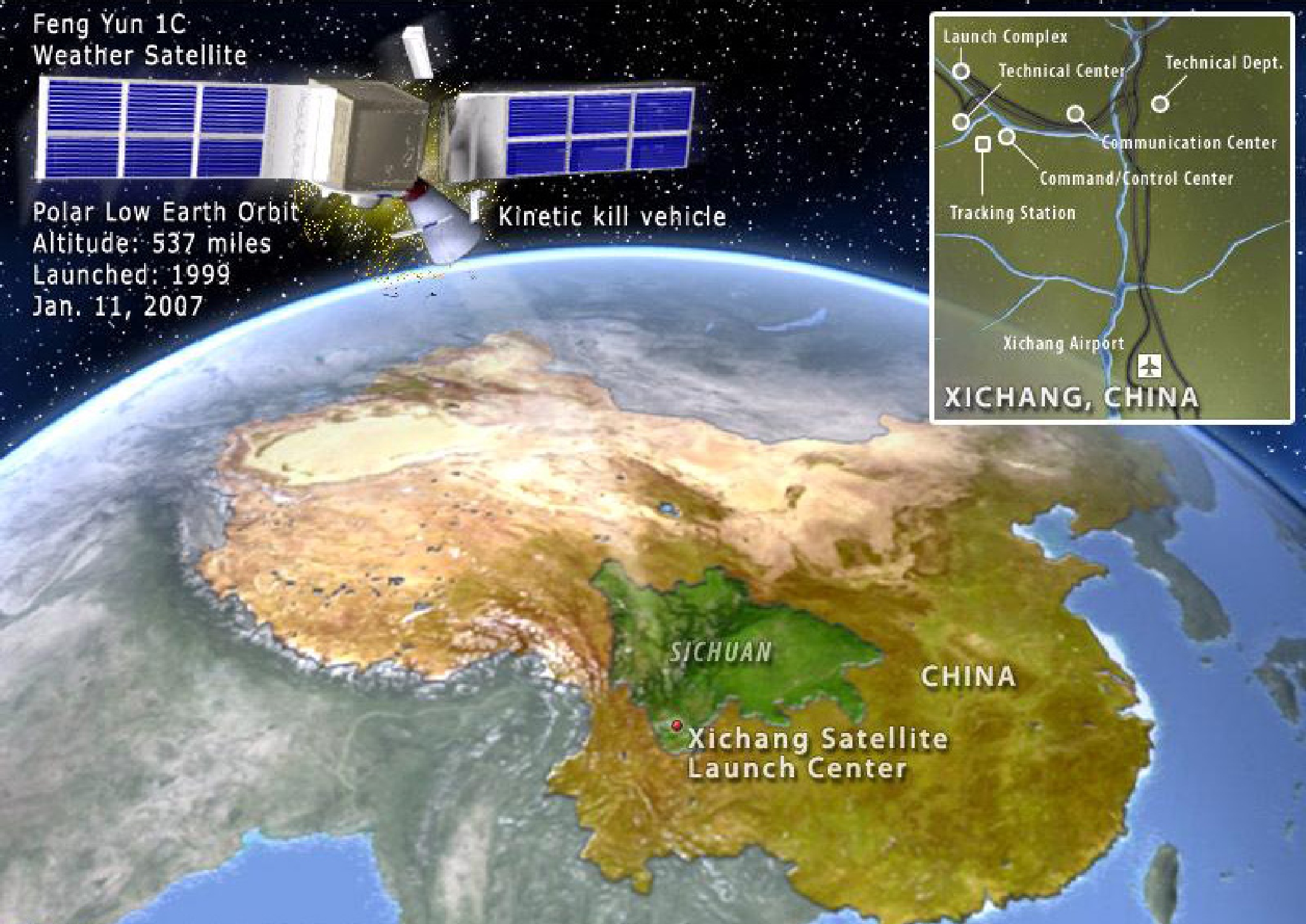

Fifty years after the Soviet Union touched off the Cold War’s space race with the launch of Sputnik, there was another salvo, fired this time by the Chinese. In 2007, Beijing launched a missile that hit one of its defunct weather satellites 534 miles high, leaving a massive debris field that floats dangerously in orbit today.

While Sputnik led to panic across the U.S. – Life magazine compared it to the shots fired at Lexington and Concord – the public’s reaction to the Chinese missile was far more muted. Inside the U.S. national security establishment, however, it was anything but. Never before had any of the country’s adversaries demonstrated the capability of shooting down a satellite. The intent of the test was clear: to put the United States on notice that its space assets were no longer safe.

“The Chinese are telling the Pentagon that they don’t own space,” Michael Krepon, former Stimson Center president and space expert, told The Washington Post at the time. Beijing’s message, he said, was a blunt one: “We can play this game, too. And we can play it dirtier than you.”

Today, that missile’s firing looks like another Sputnik moment, the beginning of a new fight above Earth between the world’s superpowers. Dan Coats, the director of national intelligence, told Congress in January that China and Russia are “training and equipping their military space forces and fielding new antisatellite weapons to hold U.S. and allied space services at risk, even as they push for international agreements on the nonweaponization of space.”

Indeed, both countries have continued to demonstrate their ability to knock out satellites with not only missiles, but by using lasers and other technologies that “dazzle” their sensors, rendering the satellites deaf and dumb. They are working on jamming capabilities as well as cyberattacks, and building robots able to fly close to other spacecraft, attach themselves like parasites, and do their worst.

Moreover, the ability to attack U.S. space architecture, now demonstrably vulnerable, has far greater consequences than it would have during the Cold War. Today, the military’s constellation of satellites is its “eyes and ears,” vital to the ability to wage modern warfare. The spacecraft provide missile-defense warnings, communication for soldiers on the battlefield, and means to spy on other countries as well as the global positioning signals that help guide precision munitions.

The ability to attack U.S. space architecture, now demonstrably vulnerable, has far greater consequences than it would have during the Cold War.

Without space, the Pentagon would go back decades in its capabilities to “industrial-age warfare,” as Air Force General John Hyten, now the head of U.S. Strategic Command, has said: “It’s Vietnam, Korea, and World War II; no more precision missiles and smart bombs – which means casualties are higher, collateral damage is higher.”

Corps, Command, Force

For years after the United States won the Cold War’s space race, American leaders assumed space was a peaceful sanctuary, out of even the most advanced military’s reach. The rude awakening has led to widespread concern in Congress, the Pentagon, and more recently, the White House, that American dominance in space is waning at a critical time.

“We have lost a dramatic lead in space that we should have never let get away from us,” Congressman Mike Rogers (R-Ala.), the former chairman of the House Armed Services Subcommittee on Strategic Forces, said in 2017, as he pushed Congress to adopt a “Space Corps.” Under his proposal, the Corps would become a distinct part of the Air Force, the way the Marine Corps is under the Department of the Navy.

According to Rogers and other proponents of strengthened space operations, the Air Force, which does currently oversee military space operations, is primarily focused on air dominance, not winning wars in space. Fighter pilots and jets consume the majority of the budget, leaving space as an often-forgotten stepchild, they argue.

The Air Force has countered that it is making strides under Secretary Heather Wilson to enhance its capabilities above Earth. It is especially interested in the potential for putting up constellations of small satellites that are harder to target. It is also looking to a growing commercial space industry that is focused on building small launch vehicles, able to fly quickly, frequently, and at a greatly reduced cost.

Space has also woven itself into official doctrine in a far more prominent way. The White House’s National Security Strategy, released in late 2017, cited space as one of its top priorities, warning: “Any harmful interference with or an attack upon critical components of our space architecture that directly affects this vital U.S. interest will be met with a deliberate response at a time, place, manner and domain of our choosing.”

President Trump called for the establishment of a “Space Force,” a sixth branch of the military and the first new department since the Air Force was created in 1947. The White House then ordered the creation of a “Space Command,” a new combatant command within the Pentagon and a step toward a full-fledged department.

Amid signs that his proposal would not garner the needed Congressional support, due in part to its possible price tag, Trump has since scaled back his intentions. On February 19, he officially directed the Pentagon to draft legislation that would create a Space Force, but one that would, at least at first, be a division of the Air Force – along the lines of the Rogers plan.

“Our adversaries... whether we get along with them or not, they’re up in space,” Trump said. “And they’re doing it, and we’re doing it. And that’s going to be a very big part of where the defense of our nation – and you could say ‘offense,’ but let’s just be nice about it and let’s say the defense of our nation – is going to be.”

A Shot inside the Fortress

If the 2007 missile shot woke up Pentagon leaders to space as a new arena for conflict, it was another launch several years later that really set off alarm bells.

In 2013, China fired a missile much farther into space – to 22,000 miles, or geostationary orbit. At lower altitudes, such as where the International Space Station lives, satellites streak over the Earth, making a full orbit in about 90 minutes. In geostationary, the orbit matches the rotation of the Earth, meaning satellites can remain over a fixed point. While China claimed the launch was for purely scientific purposes, the area is a de facto parking lot where the Pentagon and U.S. intelligence agencies have their most sensitive satellites.

Those assets are helpful for keeping tabs on North Korea’s nuclear weapons program. Or spying on the Russians. China had shown that it could hit not just the side of the castle, but inside the fortress, too.

Missiles are not the only weapons in China’s arsenal; it has used non-kinetic tactics as well. In 2014, Beijing was able to successfully hack U.S. weather and satellite systems operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, according to U.S. officials, highlighting another vulnerability – and means of attack.

Meanwhile, Russia is rapidly seeking to reconstitute its Cold War space posture, building upon its old expertise. Like China, it is developing the capability to knock out satellites in low Earth orbit with missiles launched from the ground, and should be able to do so “within the next several years,” according to the national intelligence director.

“Unlike China,” the Secure World Foundation reports, Russia is “actively employing counterspace capabilities in current military conflicts,” including in Ukraine.

Several years ago, the Pentagon was particularly concerned by the odd behavior of a Russian spacecraft. Launched in 2014, it first parked itself between two commercial communications satellites operated by Intelsat, the international satellite company, in geostationary orbit. A few months later, it sidled up to a third, getting “uncomfortably close,” as Brian Weeden, a military space expert at the Secure World Foundation, put it.

In space, a gentleman’s agreement governs the rules of the road, where satellite operators make plain where their spacecraft are located and where they are going. Collisions are bad – and costly. That’s not just because satellites cost millions to build and launch, but because a crash leads to debris, as the Chinese demonstrated. In the vacuum of space, even small pieces of junk move at 17,500 mph or so, meaning that something as small as a bolt can cause enormous damage.

'The real risk here is that these kinds of activities create misperceptions or there’s an accident that sparks conflict.'

Moreover, officials feared that the Russian spacecraft with the ability to get close was another way to possibly interfere with American satellites or collect intelligence. Still, the United States’ official reaction was restrained. The fact was that Washington was also performing these kinds of close-proximity operations, and didn’t want to impose any limitations on the Russians for fear of curtailing its own activities, Weeden says:

“As Russia and China get more capable, our freedom of action becomes their freedom of action. The real risk here is that these kinds of activities create misperceptions or there’s an accident that sparks conflict.”

Seats and Footholds

Competition and tension, if not conflict, extend to the civil side as well.

While NASA’s human space program has seesawed between returning to the Moon or to Mars – under George W. Bush it was the Moon; under Obama, Mars; now, under Trump, the Moon again – the Chinese have remained focused on our nearest neighbor. Last month, they became the first to land a rover on the far side of the Moon, a feat that can be accurately described as a giant leap.

NASA has been unable to fly its astronauts to orbit since the Space Shuttle was retired in 2011, and so it is forced to hitch rides to the International Space Station on Russian rockets – an embarrassment for a country that responded to Sputnik with the Apollo program and beat the Soviet Union to the lunar surface. Russia charges the U.S. more than $80 million a seat, and the former communist state has shown a firm grasp of the principles of supply and demand; over the past decade, when the U.S. lost the ability to fly its own astronauts, it hiked the price of rides to space by 384 percent, charging a total of more than $3 billion to get to the station.

Russia also supplies the RD-180 rocket engines used by the United Launch Alliance, a joint venture of Boeing and Lockheed Martin, giving it a firm foothold in the U.S. industrial base – and the national security arena; the RD-180 is used to power the Atlas V rocket, which the Pentagon relies on to send up its satellites. It is also the rocket NASA plans to use to eventually fly its astronauts to the International Space Station on its own.

Aware of this extraordinary leverage, Russia’s then-Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin threatened in 2014 to cut off supply, suggesting that the U.S. use a “trampoline” to get to space instead.

More recently, there have been other sources of tension. In late 2018, a Russian rocket carrying a Russian cosmonaut and a NASA astronaut failed when its side boosters did not separate properly and smashed into the side of the rocket. That triggered an emergency abort of the spacecraft, which shot the pair on a harrowing ride to the edge of space, where the astronauts experienced seven Gs, or seven times the force of gravity.

Jim Bridenstine, the NASA administrator, was present at the launch as a guest of Rogozin, now the head of the Russian space agency, Roscosmos. Bridenstine, a former Republican congressman, reciprocated, inviting his counterpart to tour NASA facilities. Given Rogozin’s previous bombast as well as his presence on the U.S. sanctions list for his role in Russia’s takeover of Crimea, there was a predictable outcry from Congress. Bridenstine was forced to rescind the invitation, a move that only further inflamed relations.

Meeting the Threat

The United States is not incapable of meeting or outpacing the competition. It has had anti-satellite weapons since at least 1985, and today, while much is classified, the Air Force’s military space program includes the mysterious X-37B, a small and sporty space plane that stays in orbit for hundreds of days at a time. The Pentagon allows only that its objectives are to develop “reusable spacecraft technologies for America’s future in space and operating experiments which can be returned to, and examined, on Earth.”

Ahead of the X-37B’s most recent mission, the Air Force gave a bit more detail, saying that it would “demonstrate greater opportunities for rapid space access and on-orbit testing of emerging space technologies.” Many national security analysts believe that vague description is code for building improved sensor technologies that would allow the Pentagon and intelligence agencies to better track what potential adversaries are doing, both on the ground and high above it.

The Pentagon’s long-awaited Missile Defense Review, released earlier this year, calls for more robust space-based systems, including a constellation of sensors to detect launches. It also says that the Defense Department will study weapons capable of shooting down missiles from space. Russia quickly condemned the review, saying the United States was further fueling the arms race above Earth, and that it was proof of “Washington’s desire to ensure uncontested military domination in the world.”

Whatever the makeup and cost of the new bureaucracy, there is one thing national security officials agree on: the threat is real and it is growing.

The Pentagon has been interested in accessing space rapidly for years. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, is currently running a program designed to produce a rocket that can launch on a moment’s notice, like an airplane. If, for example, it needed to get a reconnaissance satellite up over North Korea, it envisions doing so almost immediately. The Pentagon also has shown a keen interest in companies such as Rocket Lab, Vector, and Virgin Orbit, which are building small launch vehicles that could enable such speedy action. Rocket Lab, based in New Zealand and California, says its goal is 130 launches a year.

If the White House has its way, all of this activity would fall under the Space Force as soon as next year. Whatever the makeup and cost of the new bureaucracy, there is one thing national security officials agree on: the threat is real and it is growing. The emergence of Beijing and Moscow as significant rivals to Washington has made it clear that the next war could very well be won or lost in space.

***

Christian Davenport (@wapodavenport) covers the defense and space industries for The Washington Post, where he has worked for nearly two decades. He completed his most recent book, The Space Barons: Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and the Quest to Colonize the Cosmos, as a Wilson Center public policy fellow in 2017.

Cover photo: Artist's rendering of the Wideband Global SATCOM Satellite, part of a constellation that the U.S. Air Force says "provides flexible, high-capacity communications for the Nation's warfighters." (Courtesy of the U.S. Air Force)