The Coming Revolution in Africa

– G. Pascal Zachary

A rising generation of small farmers promises not only to put food on the African table but to fundamentally change the continent’s economic and political life.

THE HEAT IS DEADENING. After a morning picking cotton on the side of a hill, Souley Madi, wearing a knock-off Nike T-shirt and thongs made from discarded tires, staggers down a steep slope, a heavy bag of cotton bolls on his back. Reaching his small compound 10 minutes later, he greets his two wives. The older one nurses a baby while preparing a lunch of maize and cassava. The second wife, visibly pregnant, rises from a seat under a shade tree, responding to Madi’s instructions. He wants to impress his foreign visitor, so he prepares to introduce his latest agro-business brainstorm.

Ducks.

A few words from Madi, and wife number two dashes out of sight. When she reappears, some three dozen baby ducks waddle behind her. Madi beams, scoops up a duck, then hands it to me. He asks me to guess how much it will sell for at maturity.

I guess too low. Three dollars, Madi says. He is the first to raise ducks in the parched village of Badjengo, in the far north of Cameroon, about 45 minutes from the provincial capital of Garoua. Madi is a shrewd risk taker. Despite the challenging climate of Africa’s rain-sparse savanna belt, Madi’s ducks thrive, thanks partly to the diligent care provided by his new wife.

Madi, who is 41, sells nearly all of the ducks he raises, saving only a few for his family to eat. The birds are big sellers around local holidays, when Cameroonians in Europe and the United States send cash to relatives back home. Madi uses part of his duck money—about $100—to buy inventory for a small grocery store he maintains on the side of a main road. The store, a shack really, is secured by a heavy Chinese-made padlock. When people want to shop, they must first find Madi and coax him to open (he’s got too few customers to justify an employee). From the sale of cotton, dry goods, and the ducks, Madi has accumulated a cash hoard he hides in his sleeping hut.

Having finished high school, Madi is better educated than most of his fellow farmers, and he embodies an important rule in rural Africa: The more educated the farmer, the more effective his practices and the higher his income. Madi won’t allow his two school-age children to skip class in favor of fieldwork. “They should study instead,” he says.

Short and stocky, Madi sits down on a low wooden bench and begins to eat roasted corn. He tells me through a translator how he—a Muslim—took a second wife, not for status or love, but to help him take advantage of the farm boom. He complains that prices, especially for cotton, should be higher. Yet he says he’s never had more money saved.

TO AMERICANS, BOMBARDED WITH DIRE IMAGES of Africa—starving Africans, diseased Africans, Africans fleeing disasters or fleeing other Africans trying to kill them—Madi may seem like a character from a novel. But he is no fiction. Despite the horrors of Darfur, the persistence of HIV/AIDS, and the failure to end famines and civil wars in a handful of countries, the vast majority of sub-Saharan Africans neither live in war zones nor struggle with an active disease or famine. Extreme poverty is relatively rare in rural Africa, and there is a growing entrepreneurial spirit among farmers that defies the usual image of Africans as passive victims. They are foot soldiers in an agrarian revolution that never makes the news. In 25 visits to the region since 2000, I have met many Souley Madis, and have come to believe that they are the key to understanding Africa’s present and reshaping its future.

After decades of mistreatment, abuse, and exploitation, African farmers—still overwhelmingly smallholders working family-tilled plots of land—are awakening from a long slumber. Because farmers are the majority (about 60 percent) of all sub-Saharan Africans, farming holds the key to reducing poverty and helping to spread prosperity. Over the longer term, prosperous African farmers could become the backbone of a social and political transformation. They are the sort of canny and independent tillers of the land Thomas Jefferson envisioned as the foundation for American democracy. In a region where elites often seem more committed to enjoying the trappings of success abroad than creating success at home, farmers have a real stake in improving their turf. Life will still be hard for them, but in the years ahead they can be expected to demand better government policies and more effective services. As their incomes and aspirations rise, they could someday even form their own political parties, in much the way that farmers in the American Midwest and Western Europe did in the past. At a minimum, African governments seem likely to increasingly promote trade and development policies that advance rural interests.

Improved livelihoods for farmers alone won’t reverse Africa’s marginalization in the global economy or solve the region’s many vexing problems. But among people concerned about Africa—and certainly among those in multinational organizations who must grapple with humanitarian disasters on the continent—the unfolding rural revival holds out new hope. Having once dismissed agriculture as an obstacle or an irrelevance, African leaders and officials in multinational organizations recently have come around to a new view, nicely summarized by Stephen Lewis, a former United Nations official who concentrated on African affairs. “Agricultural productivity,” Lewis declared in 2005, “is indispensable to progress on all other fronts.”

The potential for advances through agriculture is large. African farmers today are creating wealth on a scale unimagined a decade ago. They are likely to continue prospering into the foreseeable future. Helped by low costs of land and labor and by rising prices for farm products, African farmers are defying pessimists by increasing their output. They are cultivating land once abandoned or neglected; forging profitable links with local, regional, and international buyers; and reviving crops that flourished in the pre-1960 colonial era, when Africa provided a remarkable 10 percent of the world’s tradable food. Today, that share is less than one percent.

“The boom in African agriculture is the most important, neglected development in the region, and it has years to run,” says Andrew Mwenda, a leading commentator on African political economy.

The evidence of a farm boom is widespread. In southern Uganda, hundreds of farmers have begun growing apples for the first time, displacing imports and earning an astonishing 35 cents each. Brokers ferry the fruit from the countryside to the capital, Kampala, where it fetches almost twice as much. Cotton production in Zambia has increased 10-fold in 10 years, bringing new income to 120,000 farmers and their families, nearly one million people in all. Floral exports from Ethiopia are growing so rapidly that flowers threaten to surpass coffee as the country’s leading cash earner. In Kenya, tens of thousands of small farmers who live within an hour of the Nairobi airport grow French beans and other vegetables, which are packaged, bar-coded, and air-shipped to Europe’s grocers. Exports of vegetables, fruits, and flowers, largely from eastern and southern Africa, now exceed $2 billion a year, up from virtually zero a quarter-century ago.

Skeptics still insist that farmers in the region will be badly handicapped, in the long run, by climate change, overpopulation, new pandemics, and the vagaries of global commodity prices. Corruption, poor governance, and civil strife are all added to the list of supposedly insurmountable obstacles. But similar challenges haven’t stopped Asian and Latin American farmers from advancing. Even people who see future gains for African farmers agree, however, that food shortages and famines will persist, at least within isolated or war-torn areas.

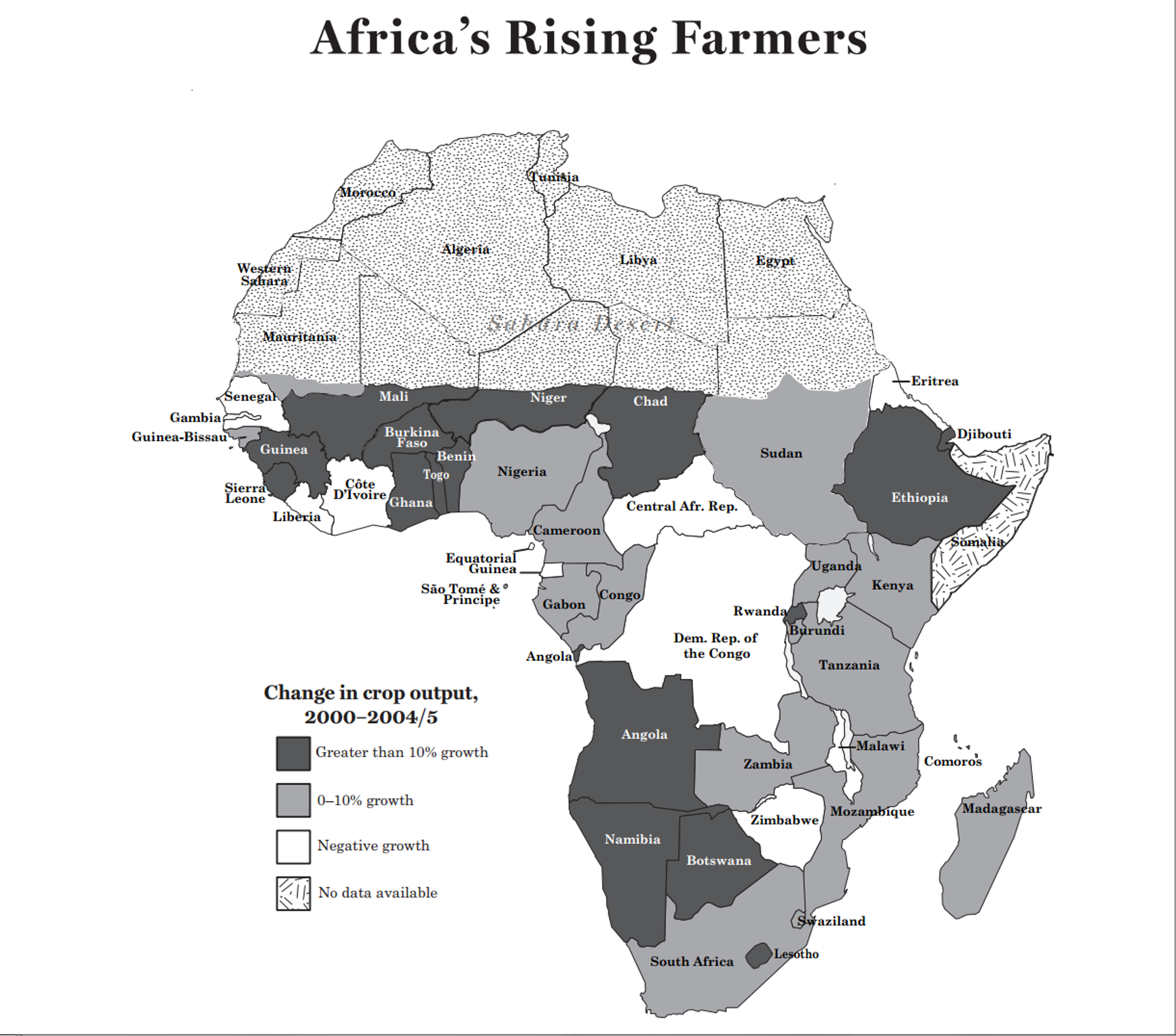

But while Malthusian nightmares dominate international discussions of Africa, food production in the most heavily peopled areas is outstripping population growth. In Nigeria, with the largest population of any African country, food production has grown faster than population for 20 years. In other West African countries, including Ghana, Niger, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Benin, crop output has risen by more than four percent annually, far exceeding the rate of population growth. Farm labor productivity in these countries is now so high that in some cases it matches the levels in parts of Asia.

“The driver of agriculture is primarily urbanization,” observes Steve Wiggins, a farm expert at London’s Overseas Development Institute. As more people leave the African countryside, there is more land for remaining farmers, and more paying customers in the city. The growth in food production is so impressive, Wiggins argues, that a “green revolution” is already under way in densely populated West Africa.

The growing international demand for food is also helping Africa’s small farmers. The global ethanol boom has raised corn prices, and coffee is selling at a 10-year high, for instance. Multinational corporations are becoming more closely involved in African agriculture, moving away from plantation-based cultivation and opting instead to enter into contracts with thousands, even hundreds of thousands, of individual farmers. China and India, hungry to satisfy the appetites of expanding middle classes, view Africa as a potential breadbasket. Finally, African governments are generally more supportive of farmers than in the past. Even African elites, long disdainful of village life, are embracing farming, trying to profit from the boom—and raising the status of this once-scorned activity.

WHILE MALTHUSIAN NIGHTMARES dominate international discussions of Africa, food production in the most heavily peopled areas is outstripping population growth.

No one model explains the surge in African agriculture. Diverse sources of success befit an Africa that, across the board, defies easy generalizations. One recent study finds 15 different farming “systems” in sub-Saharan Africa. At the level of the single African farm, diversity abounds too. Most individual farmers juggle as many as 10 crops. Outcomes among small farmers also vary. The top 25 percent of smallholders are believed to produce four to five times as much food as the bottom 25 percent. Just as in America not everyone is rich, in Africa not everyone is poor.

African farmers do share much in common. “A man with a hoe” remains an accurate description of nearly all who till the soil. Mechanization is rare. Less than one percent of land is worked by tractors. Only 10 percent is worked by draft animals. Nearly 90 percent is worked by hand, from initial plowing to planting, weeding, and harvesting. Irrigation is also rare; only one percent of sub-Saharan cropland receives irrigation water. Unpredictable weather, often drought and sometimes too much rain, bedevils farmers in many areas. Relatively little fertilizer is used; globally, farmers apply nine times as much per acre as Africans do. “Much of the food produced in Africa is lost” after harvest, according to one estimate, because of inaccessible markets, poor storage methods, and an absence of processing facilities. Finally, use of improved seed varieties is very limited by global standards.

But these sobering characteristics feature a silver lining: The potential for gains is large. Some ways farmers can move ahead are simple. One is to plant crops in straight lines. In Uganda, for instance, it was long the practice of many farmers to sow seeds haphazardly; they have been taught in recent years to plant in regularly spaced rows that vastly improve yields. When so simple a change delivers such great benefits, the importance of human choice is clear. In discussions of African affairs, the central role of the power of the individual and the desire of ordinary people to do better is often lost in a haze of dubious statistics, gloomy futuristic scenarios, and impossible calls for improved ethics, leadership, and institutions.

To glimpse a different picture of Africa, imagine traveling on a journey, not to Joseph Conrad’s “heart of darkness,” but to an uncharted, elusive, almost mythical part of the world’s poorest region, where hope, personal responsibility, and new incentives are reshaping the lives of ordinary people, turning Conradian imagery on its head.

THE FIRST STOP ON OUR JOURNEY is the village of Bukhulu in eastern Uganda. From Kampala, I take an old van jammed with 15 people and rumble along dirt roads so pockmarked that pieces of the vehicle fly off during the journey without eliciting any reaction from the driver. The next morning, from the provincial center of Mbale, I hitch a ride through the foothills of towering Mount Elgon with an agricultural extension officer who works for a South African company that pays Ugandan farmers to grow cotton for export. On the final leg of the journey, I switch to a bicycle taxi. Balanced precariously on a makeshift rear seat, the man in front cycling leisurely, I pass cornfields brimming with ripening ears nearly ready to harvest. The ride costs a dime.

I am here to visit one of my favorite farmers, Ken Sakwa, who is in the forefront of a significant yet little-noticed back-to-the-land trend. The movement is powered by city dwellers who either can’t earn enough money in the cities or are earning so much that they want to plow their savings into agro-businesses. Doomsayers constantly point to Africa’s urbanization as a relentless scourge, stripping the countryside of talent, but quietly, some Africans are going back to “the bush.” Sakwa, 37, is one of them. He spent a decade in Uganda’s mushrooming capital, doing odd jobs for cash. He enjoyed the excitement of city life but survived only because of the goodwill of relatives. Ultimately, he exhausted that goodwill. “I was a parasite,” he admits.

Five years ago, Sakwa decided to claim the vacant farm of his deceased father in Bukhulu, the village of his birth. None of his brothers and sisters wanted the land, so he got it all. His wife in Kampala refused to join him. He divorced her and went back alone.

“I knew I’d achieve if I went back to my father’s land,” he recalls. “I felt ambition inside me.”

Farmers in Bukhulu mainly grow cotton, corn, peanuts, and beans. Even the largest farms encompass no more than a dozen acres. In his first year back, Sakwa grew corn and beans on one acre, opening the ground alone, with a small hand hoe. “I worked like an animal,” he recalls. Even before his first harvest, he looked for a wife. A few months after his return, he met Jessica in a nearby village. He decided to court her when he learned her parents were farmers.

“I wanted a wife who could help on the farm and would be happy doing so,” Sakwa says. He married Jessica and, with her considerable help, he prospered. In his second year in Bukhulu, he tilled two acres of land, hiring a tractor to assist in plowing. From an American aid project, he and some neighbors learned to plant crops in straight lines. By the third year Sakwa mastered basic farming, “doing much, much better.” When his old Kampala friends visit him, they ask, “How is this poor village man getting all this money?”

Accumulation is only part of Sakwa’s story. How he spends his profits is significant. One early purchase was a mobile phone, which allows him to keep abreast of local markets and negotiate better prices for his crops. That a farmer who lives without electricity or running water should be able to receive phone calls from anywhere in the world is perhaps the most radical change in African material life in decades. Though wireless service came late to the region, nearly one in five sub-Saharan Africans now owns a cell phone, and the World Bank estimates that the region’s wireless phone market is the “fastest-growing in the world.” One morning, after he plants cottonseeds in a small field, Sakwa receives a call from the headmaster at his daughter’s boarding school (yes, he can afford that too!). The headmaster asks for 500 pounds of beans. Sakwa, who has the beans bagged for sale, wants 15 cents a pound. “Will you accept?” he asks.

The headmaster wants to pay less. Sakwa refuses. “I can hold my beans until I get a fair price,” he says.

A few days later, the headmaster calls back and agrees to the price.

ONE DAY, I WALK with the Sakwas to one of their fields. The ground is wet from recent rains. We cut through a path separating the land of different farmers and soon meet a family harvesting beans. A husband and wife and their two children are haphazardly tossing uprooted beans on a wooden cart. Sakwa greets them and stops to explain that they will fit more on the cart if they make neat piles. The man acts as if he’s received a revelation. Sakwa starts rearranging the beans to make sure the man grasps his advice. The man begins to shift the beans around, and his wife flashes Sakwa a big smile, thanking him.

We turn off the path, slice through another field, and come upon a patch of peanuts. Ever the innovator, Sakwa is experimenting with different types in order to see which grow best. He pulls a few samples from the ground to show me. Just as I begin to chew on a peanut, Jessica screams in the distance.

Sakwa races off toward his wife. I follow. When we reach her, she cries out, “Someone has stolen the beans!”

The plants have been ripped from the field. “They must have come in the night,” Sakwa says. He has been forced to hire a neighbor to guard this field in the daytime. He tells the man he will harvest the corn soon.

ONE OF SAKWA’S INNOVATIONS isn’t agricultural but commercial. In order to expand output and raise his income, he leases land from his neighbors and hires them as casual laborers, enriching them as well as himself.

Land sales are virtually impossible in rural Africa, but informal leases are becoming more common. There are no formal land titles in Sakwa’s village, nor in nearly every other African village, so his claim to his father’s land is grounded in the community’s knowledge of Sakwa and his lineage. Until recently, no one ever bought or sold rural land in Uganda, but with the rise of small-scale commercial farming the value of farmland can now be “monetized,” in rough terms, by estimating profit from cash crops grown over a period of years. Land is coming to be viewed as a commodity. Informal land deals are flexible, but because they are not supported by unassailable titles, there is always a possibility of costly disputes. Sakwa recently experienced such a problem when he leased a half-acre of very productive land from a neighbor for nearly $800. But one of the man’s brothers, who didn’t get any money in the deal, has sued Sakwa in court. He wants to be paid.

Sakwa and his friend Francis Nakiwuza are the most active acquirers of land in Bukhulu, having each leased four different plots over the past three years. The lawsuit worries them. One day Nakiwuza and I sit in Sakwa’s living room as he sifts through his business records, which he stores in a worn leather briefcase stowed under his bed. He keeps records on each of his “gardens,” listing the costs and income.

One reason for disputes: poorly drawn contracts. The lease for his newest plot, written in Sakwa’s own hand, boils down to a single sentence in which a neighbor agrees to permit Sakwa to use “my swampy land of 61 strides in length and 32 strides in width” for about $200.

The contract lacks any surveyor information and isn’t registered with any government agency or court. “We trust people,” Sakwa says.

The rudimentary contract partly reflects the inexperience of the parties involved. Desiring land is new to Sakwa, and he dreams of obtaining more. He wants to double his current holding of 10 acres. “I want to make 20 acres,” he says. “That will make my life good.”

Across the table sits Nakiwuza. He wants more land too, and brings news of a neighbor who needs to raise money. The man was caught in a sex act with a young girl. In years past, there would have been no legal consequences. But today men caught abusing underage women can go to prison or pay a large fine. For this man, the only way to avoid prison is to raise money by leasing land.

Ken Sakwa's friends in Kampala ask, “How is this poor village man getting all this money?”

Sakwa is sorry for the man but happy that either he or Nakiwuza will get to expand his acreage. “Why shouldn’t the stronger farmers have more land?” Nakiwuza asks. Often, the land they lease had been sitting idle. “We are using the land well,” he says. “Others did nothing with it. Now they have our money, and we have crops to sell.”

KEN SAKWA IS AFRICA’S FUTURE WRIT SMALL. Gilbert Bukenya is the future writ large. He is the vice president of Uganda and a rarity among African politicians: He is passionate about the value of farming, is himself an innovative farmer, and publicly encourages farmers to work smarter. One of Bukenya’s greatest achievements has been to encourage a can-do spirit in Uganda’s farmers and a sense of pride among other Ugandans in what their farming compatriots produce.

I met Bukenya one balmy afternoon at his home on the shores of Lake Victoria, where he experiments with fruits, vegetables, and dairy cattle. “By farming smarter, Ugandans not only grow more, they earn more money,” he tells me. Bukenya is an advocate of food self-sufficiency, pointing to the example of rice. Ugandans pay tens of millions of dollars annually for rice imported from overseas—sub-Saharan Africa as a whole imports nearly $2 billion worth. In order to expand the output of homegrown rice, Bukenya promoted a new African variety that grows in uplands (as opposed to paddies) and requires less water. Then he argued for the imposition of a 75 percent duty on foreign rice. The measure passed Parliament and brought rapid benefits: A few of the country’s largest rice importers invested in milling plants, thus becoming customers of local farmers. The new mills created jobs and lowered the cost of bringing domestic rice to market, so that consumers now pay more or less the same for rice as always.

Since foreign rice exporters—notably the United States, Thailand, and Pakistan—subsidize their growers, Bukenya thinks it only fair that Uganda defend its own rice farmers, even though he realizes that some import-substitution schemes fail. (And rice is only one of the African crops hampered by U.S. and European farm subsidies and trade barriers.)

Fresh from his rice success, Bukenya is now promoting the benefits of raising livestock. One September morning I find him lecturing before a classroom full of ordinary farmers, about 50 of them, gathered in a school about an hour from Kampala. Wearing a loose-fitting shirt and sandals, Bukenya jokes easily with his audience, speaking in a local language. The classroom has no electricity, a concrete floor, and exposed wooden rafters. Bukenya recalls how his mother earned the money to send him to school from sales of a beer she concocted. Switching to a prepared talk, he preaches a simple lesson: “Make money daily.” One way they can do that, he tells the small crowd, is by keeping a milk cow or egg-laying chickens. Only a few of the farmers do anything like this now, and Bukenya spends a good deal of time explaining how they can get started.

Then he criticizes the country’s traditional big-horned Ankole cattle. These animals are beautiful and beloved but provide very little milk, he says, “no matter how hard you squeeze.” He prefers European Friesian cows. “Five of them will produce the same as 50 Ankoles,” he says.

Bukenya asks one of the women in the audience to stand up. He praises the bananas she grows and notes the high output of her Friesian cows. “You are a model for the others,” he says. The woman smiles. Then, spreading out his arms and looking across the room, he says, “Everybody must be a model.”

That kind of exhortation might seem hokey to Americans, but in an African context Bukenya’s words are incendiary. It is the mental attitude of African farmers, as much as their lack of money, that holds them back, Bukenya argues. For ordinary farmers to be called heroes, or even recognized at all, by a senior political leader is unprecedented. And Bukenya’s message makes perfect sense. Surprisingly, few farmers in Uganda or other parts of Africa keep livestock. In some locales, that’s because of the extreme heat; disease is another limitation. Yet many farmers don’t raise animals (at least productive ones) even when conditions for doing so are favorable, because of the irrational pull of tradition and a lack of knowledge. But teaching skills to farmers isn’t enough, Bukenya says. “You have to instill confidence in them that by working harder, they will benefit.”

The potential for breeding (as Souley Madi knows) is large. Two government ministers in Uganda have recently launched poultry operations. Uganda’s farm output is soaring, having helped push total exports in 2006 to nearly $1 billion, double the value of 2002. Much of the growth came in agriculture: Exports of coffee, cotton, fish, fruits, and tea doubled. Corn exports nearly tripled. Cocoa quadrupled. Sesame seed exports are up nearly 10-fold. Says Bukenya, “We are doing very well, but we can run even faster.”

THE BEGINNINGS OF A PRO-FARMER POLITICAL MOVEMENT represents a watershed in African history. During the 1960s and ’70s, in the first decades after independence from European colonial rule, African political leaders blatantly exploited farmers as part of a calculated effort to speed economic development and make food cheaper for Africa’s then-tiny urban elite. They essentially nationalized cash crops, such as cotton and coffee, forcing farmers to sell everything they grew to government “marketing boards” at fixed prices, often well below the going rate. That destroyed the incentive to produce. Worse, the boards were corrupt and inefficient, and they did little or nothing to introduce farmers to new growing techniques, crop varieties, or customers. Meanwhile, the industrial schemes financed by the agricultural “surplus” virtually all flopped.

It is the mental attitude of African farmers, as much as their lack of money, that holds them back.

By the 1990s, African countries were importing large amounts of food, at great cost and sometimes under absurd circumstances. Fresh tomatoes rotted in Ghana’s fields, while canned tomatoes from Italy dominated grocery sales. The story was similar elsewhere, with the exception of South Africa. A lack of canneries and other means of preserving fresh fruit and vegetables meant that a third or more of African output spoiled.

The reliance on imported food, and the demoralization of farmers, drove many Africans from the bush to the city. But the situation also spawned a backlash. Change came in two forms. First, international aid agencies, which during the 1980s and ’90s had essentially abandoned support for agriculture and encouraged Africans to develop light industry and services, began to realize the folly of their approach. As the World Bank admitted in late 2007, “Agriculture has been vastly underused for development.”

African leaders also reversed course, albeit by fits and starts, liberalizing agriculture and permitting multinational corporations to begin buying cash crops such as coffee and cotton directly from smallholders, who were eager to sell to these private buyers after being underpaid or even stiffed by government agencies. In Uganda, once called the “pearl of Africa” by Winston Churchill because of its enormous agricultural output and excellent climate, thriving colonial-era agro-businesses were destroyed by the predations of government after independence in 1962. When a rebel leader named Yoweri Museveni assumed power in the mid-1980s, he took steps to reverse course, including a gradual dismantling of the socialized structure that made every farmer a de facto employee of the state. But the farmers, having been burned, did not respond quickly. They remembered the worthless IOUs dispensed by the government.

Besides, telling farmers to grow more is not enough; even giving them the freedom to sell to whomever they wish is not enough. Farmers need cash buyers. Without willing customers, paradoxically, growing more food can grievously hurt farmers—it raises costs and saddles them with worthless surpluses.

Incredibly, this commonplace escaped farm experts in Africa for half a century. They have learned the hard way that food shortages and famines often result not from a scarcity of food but from too much food. When farmers can’t convert their surplus into cash, they stop growing extra. No less a farm expert than Norman Borlaug, celebrated for launching the “green revolution” in Latin America and Asia, made a sobering error in Ethiopia five years ago (for which he later apologized). Having helped introduce higher-yielding grains to Ethiopian farmers, he witnessed a huge growth in output. But because no one thought about who would purchase the expanded supplies of grain, in a bumper harvest the surplus rotted and the farmers, who had borrowed money to obtain seed and other “inputs,” suffered badly.

Now farm experts are beginning to change their views, putting the customer ahead of production. In 2004, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) became the first aid donor to pledge to organize its spending around the principle that the end customer is the prime mover in African agriculture. Given a ready buyer who is offering a fair price, African farmers will defy stereotypes of their inherent conservatism and backwardness. “They move like lightning when money is on the table,” says David Barry, a British coffee buyer based in Kampala. “Cash is king.”

USAID realized that expanding farm output only makes sense when farmers respond to the right signals from buyers about which products are in demand. Part of the answer was for the agency to pay the costs of training farmers to grow those crops, and in higher-quality forms and greater volumes, that the private buyers sought. It also directly assisted private agro-firms, paying part of their costs for training farmers.

A method known as “contract farming” has become a crucial instrument of African empowerment. Buyers agree to purchase everything a farmer grows—coffee, cotton, even fish—freeing him from the specter of rotting crops and allowing him to produce as much as possible. And because the buyers—some of them domestic companies, others multinationals—profit, they have a stake in farmer productivity and an incentive to provide such things as training and discounted seed.

A wonderful example of this virtuous circle has unfolded in Uganda. The country’s largest provider of cooking oil, Mukwano, had long sold only palm oil imported from Southeast Asia. As an experiment, the company hired Ugandan farmers to grow sunflower seeds, which were then crushed into oil locally. In two years, Mukwano enlisted 100,000 farmers, hiring an experienced trainer from India, C. P. Chowdry, to organize farmers into groups, train leaders, distribute seeds, and collect the harvest.

Even though Mukwano is the only seller of the particular seed variety needed, and so sets the price, sunflowers are attractive to farmers because they require little tending or water, can be “intercropped” with corn or cotton, and are harvested three times a year. During the planting season, the company broadcasts a weekly radio program that gives advice on how to manage the crop. The effort is wildly popular among farmers. When I visited Uganda’s sunflower belt on the eve of planting season, I witnessed one farmer, Isaac Aggrey, ask Chowdry for seeds. In the previous season, Aggrey had earned a whopping $300 from three acres of sunflowers, putting enough cash in his pocket to buy a motorbike. When Chowdry told him, “The seeds are gone,” Aggrey became distraught. Chowdry reminded him that he had warned that this could happen. “Next time, set aside the money and buy as soon as we put the seeds on sale,” he said sternly.

ABOUT THE SAME TIME aid donors recognized the necessity of helping farmers grow more of what buyers want, the mentality of agricultural experts underwent a sea change. For nearly half a century, starting in the 1960s, there seemed to be an inverse correlation between the application of agricultural expertise by national and international aid agencies and the productivity of African farming: the greater the number of experts, the worse Africa’s agricultural performance.

Disdainful of the market, these agricultural specialists preferred to obsess over arcane questions about soil quality, seed varieties, and some mythical ideal of crop diversity. In classic butt-covering mode, they blamed “market failures” and Africa’s geography for farmer’s low incomes and their vulnerability to famine and food shortages.

Then, about five years ago, a few brave specialists suddenly realized that under their very noses some of Africa’s most significant farm sectors were booming—and booming without any help from the legions of agricultural scientists and bureaucrats in Africa. In West Africa, corn production doubled between 1980 and 2000. Harvests of the lowly cassava—a starchy root that provides food insurance for many people—steadily expanded. In East Africa, sales of fresh flowers soared. Once-moribund cash crops, such as cotton, saw a large expansion, first in West Africa and then in Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia. The list of improbable winners went on and on.

Even as a steady diet of stories about “urgent” food crises in Africa dominated public discussion, these successes became impossible to ignore. In 2004, the International Food and Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) published a series of papers titled “Successes in African Agriculture.” The papers both reflected and provoked a revolution in thinking about African farming. They also ended a long conspiracy of silence among aid agencies and professional Africanists. For decades the “food mafia,” led by the World Food Program and the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, had refused to acknowledge any good news about African farming out of fear that evidence of bright spots would reduce the flow of charitable donations to the UN’s massive “famine” bureaucracy, designed to feed the hungry.

Today, Africans have a much greater appreciation of the value of food self-sufficiency. Africa never spawned the industries the World Bank favored, and in the face of the withering onslaught from rapidly industrializing China and India, it isn’t likely to. Yet Africans are some of the world’s lowest-cost producers of food. And the absence of large plantations (except in parts of Kenya, Ivory Coast, and southern Africa) is beneficial. International buyers of major African crops from Europe, Asia, and the United States have told me repeatedly that small farmers in Africa, relying on their own land and family labor and using few costly inputs such as chemical fertilizers, are more efficient producers than plantations. Counterintuitively, Africa’s attractiveness to global food buyers is growing precisely because its agriculture is dominated by small farmers. And there are plenty of them.

The IFPRI report shattered the convenient consensus among experts, donors, and African governments that farmers south of the Sahara were doomed, perpetual victims who could never feed themselves and hence must permanently proffer the begging bowl. Now, because of IFPRI (itself a junior member of the “mafia”), some African agricultural successes could not be denied. That raised a logical question: If some African farmers can succeed, why can’t even more?

The sea change in serious thinking about African farming is now of more than academic interest. In nation after nation, farming is commercially viable, expanding, diversifying, and generating profits at all levels of society. Though doomsayers continue to see a bleak outlook for African farmers (the new specter is climate change), even elites are catching farm fever, recognizing that record prices for many foodstuffs, along with growing domestic markets and the possibility of expanding farm acreage in most African countries, means a brightening future.

Not coincidentally, the World Bank devotes its newest World Development Report to the status of agriculture globally, and the authors highlight Africa’s recent gains and future potential. What a turnaround. As recently as five years ago, economists at the World Bank were telling me that farm production mattered little since Africans could always import the food they needed. They would explain that Africans should exploit their “comparative advantage” in labor costs by building world-class manufacturing or service industries and allow others, “low-cost producers” elsewhere in the world, to deliver the necessary foodstuffs to African cities.

THE MARRIAGE OF CAPITALISM AND AGRICULTURE is not a panacea for rural Africans. Uganda and Cameroon boast some of the best land in the sub-Saharan region. Many other African countries are doing well enough in farming that they can continue to raise output and incomes rapidly by working smarter, notwithstanding the challenges of climate change and poor soil. Yet a few parts of Africa live up to the nightmarish visions of the pessimists.

Malawi is one of those places. In this poor southern African country, Lorence Nyaka, a postal worker turned farmer, is fighting a losing battle.

On less than an acre of dry and dusty land, Nyaka, who is 51, tries to support his wife, Jesse, and 10 children, growing corn and cassava with only a hoe. Without fertilizers or irrigation, his yields are poor and he’s totally dependent on uncertain rains.

Not long before I visited Nyaka, he lost a third of his land to his wife’s brother, who had become old enough to collect his share of the family’s inherited property. As he explained the situation, Nyaka slashed at a patch behind his house that was barely larger than a pool table. He was preparing furrows for corn seeds that he would plant at the onset of the rains, still months away.

Worse, thanks to disease, Nyaka has more mouths to feed. AIDS took the lives of Jesse’s brother and his wife, so their four children now live with the Nyakas. That means less food for their own six children, but to Nyaka his obligation is clear. “If I don’t help these children,” he says, “they probably die.”

In these parts, people are so crowded that there’s little space for cattle or other domesticated animals. Nyaka does have six chickens, one of which stays, for safekeeping, in his bedroom.

“Our problem in Malawi is we do work hard, but we don’t get enough food,” Nyaka says. He and his family subsist on a diet of cassava and a fluffy corn dish called nsima; both provide calories but scant protein. There is nothing he can do, he says, to alter his routine except wait for the rains—and pray. His fatalism, however frustrating, is typical of poor farmers in these parts.

In truth, Nyaka’s options are limited. Thomas Malthus, the English economist and demographer, is getting his revenge on Lorence Nyaka and hundreds of thousands others in Malawi, the most densely populated country in Africa, where 13 million people jam into a narrow strip of land. Two hundred years ago, Malthus described a world undone by too many people and too little food—a world much like Malawi today, where life expectancy is less than 40 years and food shortages are chronic. With about half its population under the age of 15, Malawi is expected to approach a population of 20 million by 2020.

While much of the world now worries about the effects of plunging birthrates and declining populations, in Africa overpopulation remains the most serious threat to well-being, and perhaps nowhere is the problem worse than in Malawi, a 550-mile-long wedge between much larger Zambia and Mozambique. “The challenge here is to enable the population to survive,” says Stephen Carr, a specialist on rural development who has worked in Africa for 50 years.

Few Malawians use birth control, and any coercive action to cap family size is unthinkable. Nyaka says that whether he and his wife have more children “depends on God.” Even in the midst of the AIDS pandemic—one in five Malawian adults is HIV positive—condom use is infrequent. Only one in two Malawians can read. The government seems confused, at best, over how to help farmers. “The distribution of the spoils of office takes precedence over the formal functions of the state, severely limiting the ability of public officials to make policies in the general interest,” according to a 2006 study from a British think tank.

Carr, who advises the World Bank, says that migration “may be the only way to prevent a Malthusian meltdown.” With aid from the World Bank, the Malawian government has started a resettlement scheme, bringing people from the country’s overcrowded south to the north, but the effort helps relatively few. Another possibility is to encourage people to leave the country, just as migrants left Germany and Ireland during times of economic hardship. Land is plentiful in neighboring Mozambique, for example, and many people in both countries speak the same indigenous language and share customs. Zambia, another neighbor, needs more farm workers for its fertile land. Mobile Malawians could benefit both countries.

Time and again, of course, human ingenuity has provided an escape hatch, giving the lie to Malthus’s central claim that population growth invariably outstrips food production. In Malawi, however, the chances are growing that his grim forecast is right on target.

While much of the world worries about declining birthrates, overpopulation is the most serious threat to Africa's well-being.

Even here, though, there is reason for hope, if only farmers can be roused to do more. Nyaka, for instance, lives within 200 yards of a working well. Water flows all day long. If he carried water to his land, he could bucket-irrigate vegetables during the long dry season. When I ask him why he won’t irrigate in this manner, he creases his brow and shakes his head. The possibility is inconceivable.

Yet 30 miles away, outside the old colonial town of Zomba, nestled in the central highlands of Malawi, Philere Nkhoma, an inspired trainer in one of the Millennium Villages demonstration projects masterminded by Columbia University economist Jeffrey Sachs, is showing farmers the benefits of hand-irrigation. On the morning I visit, dozens of men are dripping water on row after row of vegetables in a “garden” the size of a football field. This method of babying high-value crops goes beyond watering. While Nkhoma chews on a piece of sugar cane, men feed spoonfuls of fertilizer to a row of cabbage plants. Nkhoma shouts encouragement to one farmer, addressing him as “brother” and complimenting him on his effort. “One secret of this thing,” she says later, “you need to know how to speak to the people. You should make sure you’re part of them.”

Nkhoma’s close involvement with hundreds of small farmers in central Malawi won’t grab headlines, but it represents a radical new beginning for farmers, long ignored by the very people paid to help them. Malawi’s “agricultural extension service has collapsed,” according to a confidential British report. The gap is partly filled by aid projects such as the one that employs Nkhoma, whose own life story mirrors the shift in the status of farming in Africa. She’s part of a new generation of urban Africans unafraid of getting their hands dirty. After more than 10 mostly frustrating years as a government farm adviser, she was chosen by a foreign donor to earn a bachelor’s degree in agriculture. After graduation she joined the Sachs project, where she has wide latitude to innovate and the resources to carry out plans. “If you have an energetic extension worker, you only need to change the mindset of the people,” she says. “When that happens, change can occur very quickly.”

Indeed, last fall Malawi posted a record corn crop, far exceeding expectations and eliminating, at least for now, any threat of general famine in the country.

MEN AND WOMEN DO NOT LIVE BY BREAD ALONE. I am reminded of this cliché on a cool September afternoon in Kampala, where I meet Ken Sakwa inside a fast-food restaurant called Nando’s. Sakwa is in the capital alone, having traveled from his village in eastern Uganda in a rickety van. He looks fit, if a bit thinner than I recall him.

As we munch on grilled chicken and french fries, he recounts his latest achievements. In February he leased another piece of land, bringing his total acreage to 12, and he now regularly employs six of his neighbors to help him work his fields. In a sign of his standing in his community, village elders brokered a favorable settlement of his vexing dispute with the brother of a neighbor from whom he had leased land. Managing the resentments of less prosperous farmers in the village remains a burden. Sakwa tells me that lately he has been finding small bottles, stuffed with curious contents, near his house. He ignores them, though he knows they are meant as a form of juju, intended by his neighbors to put a hex on him. To smooth relations, Sakwa now lends money to people in need, but he admits, “I usually don’t get paid back.”

Sakwa’s success is indeed striking. He has saved more than $10,000 out of his farm profits over the prior five years, and he’s now constructing a large commercial building along the main road near his village. He plans to rent out about a dozen shops, then sell the building and bank his profits.

While we talk, one of Sakwa’s cousins, a younger man who lives in the city, joins us. “My relatives in Kampala think I am rich now,” Sakwa says. “But I feel I overwork myself.” He normally works from dawn until dusk, and unlike many farmers he never drinks alcohol, sparing himself the expense of buying the local brew from the makeshift village pub.

I ask Sakwa whether he might make an exception today and share a Club beer with me. We have something to celebrate. His wife, Jessica, gave birth to twin daughters a few months before, and I imagine he must be proud. He says nothing. When his cousin steps away to the toilet, Sakwa whispers to me, “The children are sick.”

He adds, “I am here to get medicine for them.” Oh, no. Earlier, I told a friend of mine that Sakwa was traveling to Kampala for no apparent reason. She is from the same region and ethnic group as Sakwa and guessed that he must need “special” medicine that he is afraid to obtain near his village. I scoffed at her suggestion. I lean toward Sakwa and say softly, “Your newborn babies have AIDS.”

Sakwa purses his lips and nods. Suddenly, his loss of weight seems ominous. His eyes look gaunt. “And you?” I ask.

“I tested positive. Jessica also.”

I ask Sakwa if I can telephone my friend. She counsels people with the disease, helping them to get services and anti-retroviral drugs, often provided at no charge by foreign donors and the government. The ARVs are indeed remarkable, bringing many years of health to most who take them properly.

An hour later, I sit in an outdoor café with Sakwa and my friend. They immediately begin speaking in Gisu, the language of their ethnic group. “You can still be a successful farmer, even more successful,” she tells Sakwa. “So long as you get treatment, you can still farm as well as you do now.”

I wonder whether he believes her. She looks him in the eyes and says, this time in English, “Don’t let the disease take away your success.”

The woman, who is a few years younger than Sakwa, realizes that her sister attended school with him. She promises to help him and Jessica get treatment quickly.

Sakwa thanks us when he leaves. It is night in Kampala now, and I sit in the darkness. The electricity is out, and I clutch my Club beer, sipping at the bottle even though it is empty.

My friend orders me another beer, and a soda for herself. “It is good we can deal with what is,” she says.

* * *

G. Pascal Zachary teaches journalism at Stanford University and is finishing a book on Africa for Scribner.

Photo courtesy of Flickr/Carsten ten Brink