Fall 2016

The Communist Domino That Would Not Fall: China’s Resilience at the End of the Cold War

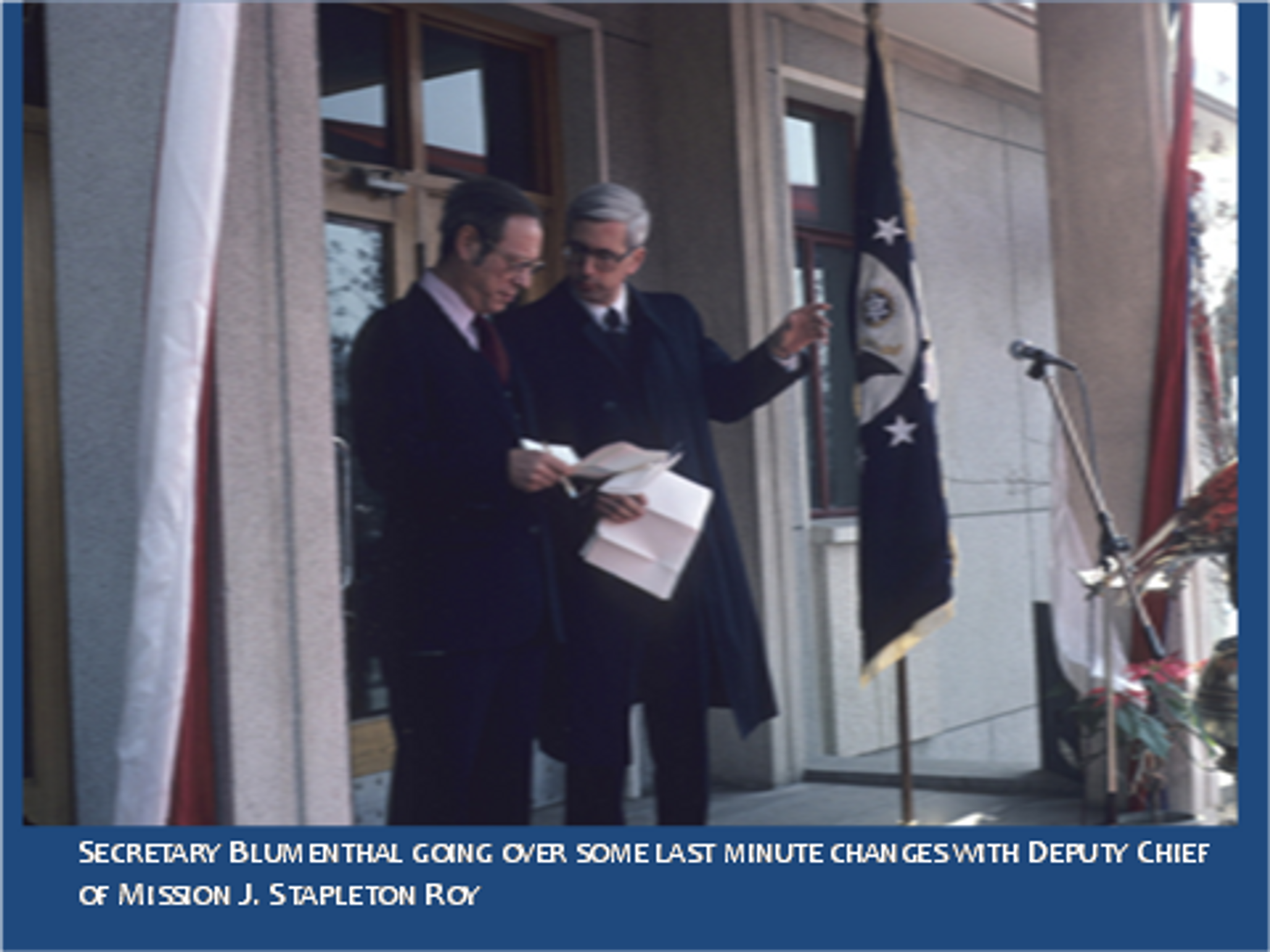

– J. Stapleton Roy and Charles Kraus

As the communist world was crumbling, China stood alone. Stapleton Roy, former US Ambassador to China, gives insight into his post to Beijing 25 years ago and the global geopolitical currents that were roiling at the time.

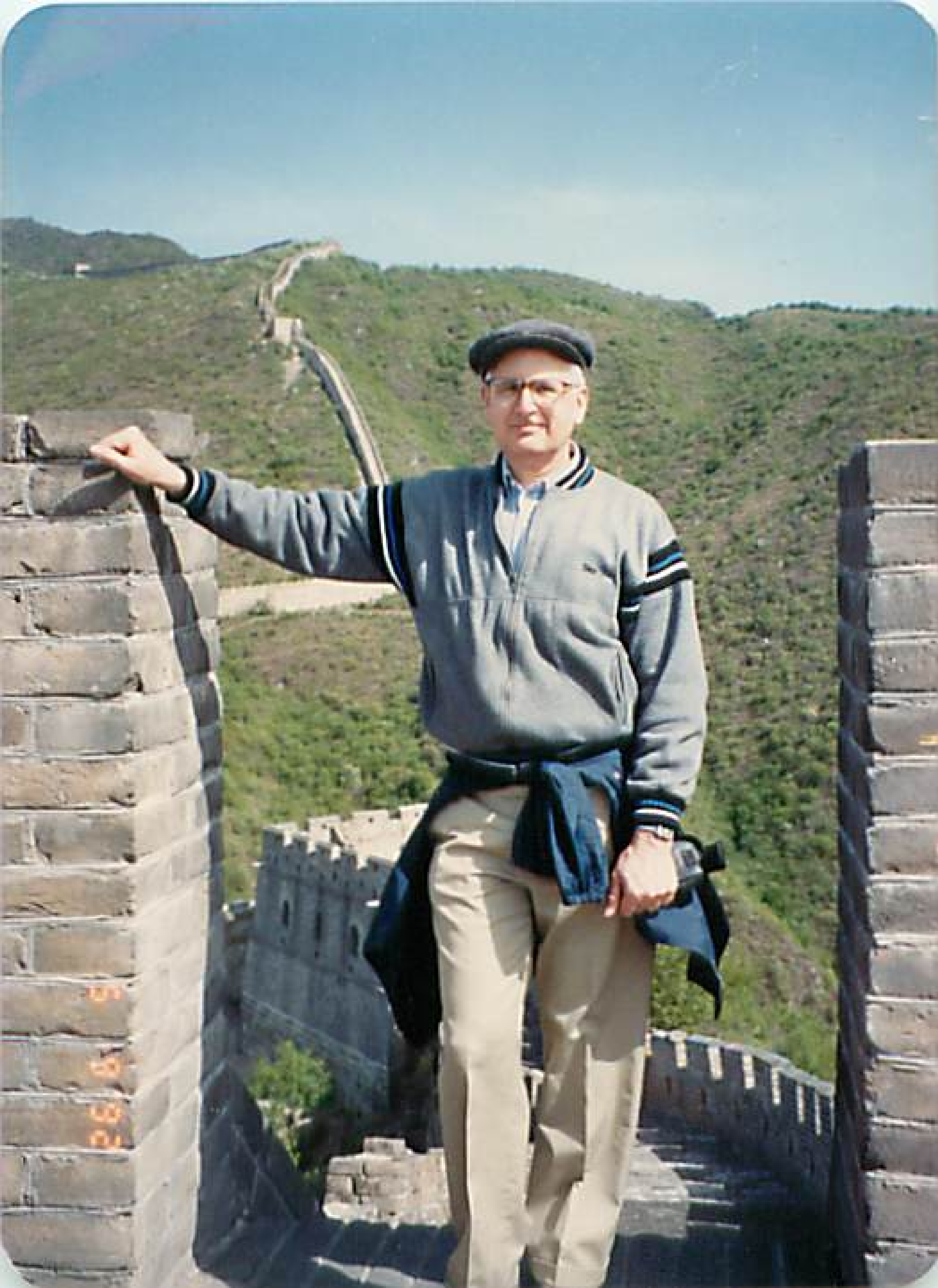

Charles Kraus, a China specialist and Program Associate with the Wilson Center’s History and Public Policy Program, sat down with Stapleton Roy, former US Ambassador to China and Director Emeritus of the Kissinger Institute, to talk about China and the break-up of the Soviet Union. Ambassador Roy joined the US Foreign Service immediately after graduating from Princeton in 1956, retiring 45 years later with the rank of Career Ambassador, the highest in the service. During a career focused on East Asia and the Soviet Union, his ambassadorial assignments included Singapore, Indonesia, and of course, China. He arrived in Beijing in August 1991, just as the coup attempt against Mikhail Gorbachev was taking place in the Soviet Union. In 2008 he joined the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars to head the newly created Kissinger Institute

Their conversation focused on the collapse of the Soviet Union and the tense diplomatic atmosphere in which Ambassador Roy assumed his post in 1991. The communist world was crumbling, and it was unclear to outside observers whether China would be the next domino to fall—speculation of which the Chinese leadership was keenly aware. The conversation below covers developments both within and outside of China at the end of the Cold War, painting a picture of domestic tumult and existential questions within China itself but also of a United States which fundamentally misunderstood China’s trajectory at this critical juncture.

Charles Kraus: Ambassador Roy, you arrived in China in August of 1991. This was only two years after the tragedy at Tian’anmen Square, and the bloody crackdown on student protests. The Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party Zhao Ziyang had also been purged. Can you describe what it was like to go to China at this time, what was the sting of the Tian’anmen tragedy, and how did it affect US-China relations, and your work on the ground in Beijing?

Stapleton Roy: It was a very exciting time when I went to Beijing….During this period we had the coming down of the Berlin Wall, and we had the gradual loosening of the Soviet grip on Eastern Europe, but at that time it was not anticipated that the Soviet Union itself would dissolve. When I arrived in Beijing in August of 1991, it was right at the time of the August Coup against Gorbachev, that began the process of the breakup of the Soviet Union, and in fact when I presented my credentials to the president of China, it was during the coup and both of us had been watching the events in Moscow on CNN and that was the topic of the conversation I had with him after presenting my credentials. The breakup of the Soviet Union was very significant, it had a domestic impact in China, and it had an international impact. Domestically, there had been a sort of glamor about the US-China relationship because even though China and the United States achieved a great breakthrough that led to the establishment of diplomatic relations, during the final stages of Cultural Revolution, when conditions in China were terrible, but everybody recognized that this was a breakthrough of enormous significance, and in fact it was the turning point of the Cold War. Psychologically after 1972 when President Nixon went to China the United States became self-confident that the trend of history was on our side. Even though we didn’t expect there to be breaking up of the Soviet empire.

When the events in June of 1989 occurred, it essentially destroyed the image of China in the United States. James Lilley our ambassador to China at that time had a very difficult time because one of the dissidents had achieved asylum at the US embassy attitudes were very hostile to our embassy in Beijing. As a result Ambassador Lilley’s assignment ended after two years and I was sent in as his replacement. Attitudes in the United States were hostile to China. The issue of China was being used by Democrats in Congress to attack a president whose big strength was foreign policy. On most issues they had no ability to criticize his handling of things. They seized on the China issue which was of course of particular interest of his because of his earlier assignment as the head of the offices in Beijing. So I arrived in China under these circumstances, and the first thing that occurs after I arrive there is the beginning of the process of the unraveling of the Soviet Union .

So this had two important consequences: One was domestically in China. The events in June of 1989 had undermined the legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party and some of the people watching what was taking place in Beijing in 1989 thought that communist rule in China might be coming to an end. In fact that was not the case. And China was able to restore stability in China, so when I arrived in China the legacy of Tian’anmen was no longer an active event in China. But the international impact of the events in Tian’anmen were still very alive and as the Soviet empire began to unravel, with the loosening of Soviet control over the Eastern European satellite states and then the gradual declarations of independence by the individual republics of the Soviet Union. It looked as though communist rule was collapsing globally, and that meant many people wondered whether this was going to have an impact on China. The Chinese leaders were very conscious of this. So this was a very delicate time in China. Because not only not only was the communist world losing the position that it had occupied since world war 2, but China itself was in the spotlight as to what might happen.

So one of my early challenges in China was to convince Washington that it should not base policy toward China on the assumption that communist rule in China was about to collapse because in fact, our understanding of the situation in China in that time was that stability had been restored and that the ruling group in China was not under any immediate challenge that might threaten its rule.

So one of my early challenges in China was to convince Washington that it should not base policy toward China on the assumption that communist rule in China was about to collapse because in fact, our understanding of the situation in China in that time was that stability had been restored and that the ruling group in China was not under any immediate challenge that might threaten its rule. The second impact of the collapse of the Soviet Union was it removed the Soviet threat. I think we all know that the breakthrough to China occurred in 1971 and ‘72 because the United States and China were both so concerned by the Soviet threat that they decided that cooperation between them was worth doing even though we had a hostile relationship up to that point and from ’72 until we established diplomatic relations in 1979, and then from the decade after that, we had been busily trying to expand our relationship with China based on our common sense that the Soviet threat still was a potential danger to our national interests.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, all of the sudden that rationale was removed, and this occurred at a time when the image of China had turned hostile in the United States, and so that meant, with a new administration coming in in Washington the strategic underpinnings of the US-China relationship had been removed, and as you recall the Clinton administration began with the sense that the primary focus of our relationship to China would be human rights. And early in my assignment there, the President made the decision to attach human rights criteria to the US decision as to whether or not we would renew their Most Favored Nation trading privileges for China. So not only did I have hostile public opinion in the US that affected the relationship, but I also had an administration that no longer had a clear sense of what the strategic basis for dealing with China should be. So there was a significant impact on the US-China relationship from both of these developments

CK: You had mentioned that, as you were presenting your credentials you watched on TV with your Chinese counterparts, news of what was happening on in the Soviet Union. How else did you keep appraised of what China and Chinese leaders were thinking about what was going on in the Soviet Union? Was this a frequent topic of conversation you had with Chinese counterparts, or were you mostly reading the tealeaves in the media, in the Chinese media?

SR: Embassies do both. Our embassy was still relatively small but it was very, very competent, and naturally we had contacts throughout the Chinese government, we had contact throughout the diplomatic community, there was a Soviet embassy in Beijing at the time and the US embassy was in touch with them, so we could not only go out and talk to Chinese to get their impressions of what was going on, but we also could talk to our diplomatic colleagues some of whom were Eastern Europeans or neighbors of the Soviet Union, some of them were the Soviets themselves, and we had contacts with all of those people, plus we had access to the international news media, and we had the experience that many of the officers had already developed over the decades before that.

CK: And based on what you had previously said, you had sensed that stability would prevail in China, even as communism was collapsing in the Soviet Union. On the other hand, many people held different views; many people thought the same thing could happen in China. What was the source of your view that China would endure and continue to be led by the Chinese communist party even after 1991.

I remember when I arrived in China in 1978 we had to bring with us all of the everyday necessities you would expect to use in a post, and when I went back to China 10 years later, all of those commodities were available freely in China. So the price reform had had a dramatic impact on what was produced in China but at the same time it resulted in enormous increases in the prices of everyday commodities. And the result was it wasn’t simply the political ferment that was made possible by the opening up of the domestic environment in China but there were also these economic difficulties that people had to cope with because of the changes in price structures that affected their everyday lives.

SR: The principal change was on the part of the Chinese themselves. What made the 1989 events so difficult for the Chinese Communist Party to deal with was there was considerable sympathy for the desire of the student demonstrators in Tiananmen for an opening up of the political system. And if you recall the demonstrations occurred because of the death of Hu Yaobang who had been liberal-minded General Secretary of the communist party in the early 1980s he was removed in 1986 by Deng Xiaoping because the reform and openness process had resulted in some instability in student populations around China and Deng felt that Hu had not been handling that with sufficient rigor to maintain stability so he was replaced by Zhao Ziyang who up to that point had been the premier. So in the lead up to Tian’anmen we had this ferment taking place in China, and in the middle of the decade China carried out a price reform which completely transformed the economic system in China, up to that point the desirable goods in china were all in scarce supply. I remember when I arrived in China in 1978 we had to bring with us all of the everyday necessities you would expect to use in a post, and when I went back to China 10 years later, all of those commodities were available freely in China. So the price reform had had a dramatic impact on what was produced in China but at the same time it resulted in enormous increases in the prices of everyday commodities. And the result was it wasn’t simply the political ferment that was made possible by the opening up of the domestic environment in China but there were also these economic difficulties that people had to cope with because of the changes in price structures that affected their everyday lives. So it was the combination of these things that came together, and what it did was it produced a split in the communist party leadership over how they should be managed, with some people such as the General Secretary Zhao Ziyang believing that China should accommodate this process and others believing that it had already gone too far, and there should be a crackdown. And it was the events in the lead up to the Tian’anmen events of June of 1989 when this split became acute and this led to the removal of Zhao Ziyang as the Secretary General of the Chinese communist party. So this was a period of great ferment in China. While the students were in the square, many people in the bureaucracy in China were sympathetic to what the students were doing. But when I returned to China in 1991, I found that that sympathy had changed. The conclusion of the people who had been most sympathetic to the student demonstrations was that it had gone too far, it had set back the reform process in China, and that the government was justified in cracking down in order to maintain stability, because there is a general feeling in China, based on its modern history during the 20th century that instability is the biggest threat to China. Therefore, anything that threatens stability tends to cause people to support efforts to intervene in order to maintain stability. So that was the prevailing mood when I came back. So I had been in China in 1989 on visits, and when I went back in 1991 I found the mood had changed very significantly.

CK: So it sounds like in the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union, you believe the United States got its China policy wrong in the sense that the administration failed to come up with an overarching priority for the relationship that could replace the former Soviet threat. What would you say the United States got right in its china policy in the immediate aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union?

SR: Well we have to differentiate here. I think the technical aspects… I thought it was a mistake at the time, but I did my very best to carry out the president’s decision to achieve improvement in various areas of human rights. And in fact, I found the Chinese were willing to work with us on that question, but this was during the Clinton administration. In the Bush administration, the real problem for the President was trying to salvage the relationship because of the damage caused by the television coverage of the bloody crackdown in Beijing in June of 1989. The Clinton administration came in with an ideological view of China as opposed to a carefully considered objective view of what the circumstances were in China. If you recall during the presidential election campaign in 1992, candidate/governor Clinton compared Beijing to Baghdad. Well in fact the comparison between Beijing and Baghdad was not an accurate one. Beijing was very, very different, Beijing was carrying out a… even though the reform process had been pushed back, but… before the president took office you had the 14th Party Congress in China, in the fall of 1992, and it had pushed the Tiananmen freezing of the reform process in China behind it, and it had strongly reaffirmed the reform and openness policies that Deng Xiaoping had initiated at the beginning of the 1980s. So the Clinton administration came into office critical of China for its crackdown on Tiananmen at a time when China was putting Tiananmen behind it and moving rapidly toward economic development. The American business community spotted this trend immediately. Washington was not interested in that trend. Washington still saw China as a pariah state, with a bad domestic human rights situation, and it wanted to use the economic leverage that we had with our trade relationship in order to force China to bring about significant improvements in various human rights areas within one year. That was an unrealistic goal, but my judgment as ambassador was- it would be possible to make progress in all of the areas, but how significant that progress would be remained to be seen. My problem was, there was a dispute in Washington, between those who, having put the linkage between human rights and Most Favored Nation treatment of China in place, they didn’t to remove them. So in their view, no matter what China did, they wanted to keep those linkages in place, whereas other people in the administration recognized that China’s economy was growing rapidly again, and we ought to be trying to expand our trade relationship with China. So there was a dispute in Washington, which made it impossible for me as American ambassador to get guidance from Washington that I could use in working with China in trying to get human rights improvements, because if you want somebody to do something, you have to be able to tell them what you will do, if they are prepared to do what you are asking them to do, and Washington was frozen up on that process. So this was a very difficult time in managing the US-China relationship, but the general intent of the Clinton administration was to improve our relations with China, and after the President made the determination in 1994 to break the linkage that we had put on in 1993, we actually began to resume visits to China at the cabinet secretary level; our secretary of Defense came, our secretary of Commerce came, our secretary of Labor came, and finally our relationship began to be slowly moving back toward a more normal situation.

So the Clinton administration came into office critical of China for its crackdown on Tiananmen at a time when China was putting Tiananmen behind it and moving rapidly toward economic development. The American business community spotted this trend immediately. Washington was not interested in that trend. Washington still saw China as a pariah state, with a bad domestic human rights situation, and it wanted to use the economic leverage that we had with our trade relationship in order to force China to bring about significant improvements in various human rights areas within one year.

CK: What do you think the key lesson that China drew from the collapse of communism in the Soviet Union in Eastern Europe was? If they drew one, big, broad lesson from this experience, what was it for China?

SR: They did a thorough assessment of what it was that caused the Soviet regime to collapse so suddenly in the Soviet Union, because China had no more anticipated this than other outside observers. Their conclusion was that the villain was Gorbachev. They felt that he had opened up the system much too rapidly without delivering any economic benefits. In other words, they saw his reformasi and glasnost policies as increasing instability factors in Soviet Union without delivering the benefits that could shore up the wisdom of the changes that were taking place. So in their minds, Gorbachev became the symbol of what China itself wanted to avoid, so while they were rapidly implementing very far reaching market reforms in China’s handling of its economy they kept a very tight grip on the political system, in order to avoid making what in their view was the mistake that Gorbachev had made.

CK: Ambassador Roy, thank you very much for sharing your thoughts on the end of the Cold War and the changes in the US-China relationship.

* * *

Charles Kraus is a China specialist and Program Associate with the Wilson Center’s History and Public Policy Program.

J. Stapleton Roy is former US Ambassador to China and Director Emeritus of the Wilson Center's Kissinger Institute on China and the United States.

* * *

Cover photo courtesy of Flickr/Yinan Chen