The Dead Sea isn't dead… yet

– Laura Kurek

A water crisis could dry out the biblical salty lake, and the proposed solution is rife with problems.

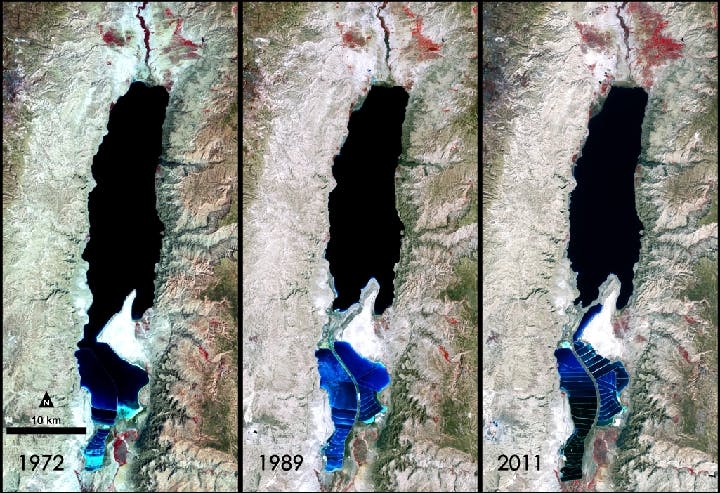

The Dead Sea is fighting oblivion. Renowned for its cobalt waters, high salinity, and religious significance, the biblical lake faces a slow death as its tributary, the Jordan River, is continually overdrawn to satiate the demands of Jordan, Israel, Lebanon, and Syria. Each year, the Dead Sea’s water levels drop by approximately 3.3 feet.

The desiccation of the Dead Sea is a part of a greater water crisis unfolding in the region. Israel, Jordan, and Syria syphon water from the Jordan River to grow crops and provide potable water for their people — demand that spiked with the arrival of Syrian refugees. As a result, 90 percent of the Jordan River no longer flows into the Dead Sea. Some researchers estimate that, without intervention, the sea will be reduced to a puddle by 2055. Beyond the question of survival, tourism and mineral industries evaporate as the sea recedes. More troubling still are the massive sinkholes: fresh water from underground aquifers can seep into salt deposits in the dried seabed, dissolving the salt and creating cavities that ensnarl buildings, roads, and humans.

For decades, scientists have warned of the Dead Sea’s demise, spurring action that has heretofore been inadequate. Serious discussions on how to save the Dead Sea began in the 1990s. In an early proposal, a pipeline connecting the Red Sea to the Dead Sea would have provided 900 million cubic meters (cbm) of water annually to be desalinated for civilian use. Another 900 million cbm would be added to the Dead Sea each year, allowing it to maintain its volume. Scientists voiced their concerns. Red algae from the Red Sea might float on the buoyant Dead Sea’s surface and, with relentless sunlight, the invasive species could multiply and stain the Dead Sea crimson. For a region so intertwined with Abrahamic faiths, the irony would not be missed. (Think Moses turning the Nile River into blood). Gypsum could form due to the incompatibility of the Red Sea and Dead Sea’s respective mineral contents, coloring the Dead Sea a chalky white. Other scientists took issue with the pipeline itself, which transverses an earthquake zone; if the pipeline should leak, underground freshwater aquifers could be contaminated by salt, compromising water stores for local farming and consumption.

With such dismal scenarios predicted, Jordan, Israel, and the Palestinian Authority asked the World Bank to conduct a $16.5 million study to investigate the risks. The World Bank’s verdict conceded that 900 million cbm a year of Red Sea water would potentially dye the Dead Sea milk white or blood red, and would definitely spoil underground freshwater. The three party states scaled back their ambitions and agreed in December 2013 to build the Red Sea Dead Sea water conveyor (RSDSWC), a 112-mile pipeline that will transport a reduced 200 million cbm of water annually.

The RSDSWC will refill the Dead Sea while providing potable water to the region, courtesy of a desalination plant at the Gulf of Aqaba. The drinkable product — 80 million cbm per year — will be divvied between the Israelis and Jordanians. The Israelis, in turn, will sell freshwater from the Sea of Galilee to Palestinians and Jordanians. This exchange is intended to ameliorate both regional water scarcity and fraught diplomatic relations: “Building the pipeline will enhance political stability and have an overall positive effect on the peace process as these countries work together,” said World Bank water specialist Alexander McPhail. The briny water from the desalination process will be slowly introduced into the Dead Sea to counteract its retreating shoreline. At a rate of 80 million cbm annually, the Red Sea water should not cause severe changes in coloration as the earlier, larger-scale proposal would have.

A microscopic frontier lies at the bottom of the Dead Sea

It sounds like an innovative idea to remedy an environmental concern and bridge a political chasm, right? Unfortunately, there’s a catch.

The Dead Sea’s namesake comes from its high salinity, long thought to preclude life from forming. In 2009, German marine scientist Danny Ionescu found otherwise. Exploring freshwater springs that dot the seabed, Ionescu discovered species never before seen: “Life [was] screaming at us — an entirely new microbial ecosystem in the Dead Sea.” The Dead Sea, in fact, is living.

Ionescu’s discovery of these primitive lifeforms — species with fantastic abilities, including their survival through severe oscillations in salinity — could further our understanding of life’s origins. The presence of these creatures, however, complicates the RSDSWC project. Ionescu predicts that Red Sea water would enable these organisms to thrive at the sea’s surface – changing its color, a problem thought to be solved by the RSDSWC’s slower flow design. Ionescu and other scientists hypothesize that Red Sea water, no matter how quickly or slowly added to the Dead Sea, will dissolve salt deposits, create more sinkholes, and contaminate local freshwater. A new species of green sulfur bacteria discovered by Ionescu could accelerate the process.

A microscopic frontier lies at the bottom of the Dead Sea, but its discovery came too late to be considered in the World Bank’s report. The RSDSWC project has been greenlighted and is scheduled to be operational by 2018. How this miniature ecosystem will react to Red Sea water remains unknown. Ionescu and other scientists, meanwhile, urge consideration of alternate solutions, such as charging factories fees for diverting Jordan River water that would otherwise feed the Dead Sea.

In reality, protecting an ecosystem is not as seductive as the potential of regional peacebuilding. The diplomatic and environmental outcomes of the RSDSWC remain to be seen, as does the ability of scientists to convince policy-makers to proceed with caution. In the brawls between science and politics, though, history has favored the politicians.

* * *

The Sources: Pamela Weintraub, “The Dead Sea Lives! Why scientists question the longstanding plan to merge the Dead Sea and the Red Sea,” Nautilus, 2015.

Suleiman Al-Khalidi, “Jordan, Israel agree $900 million Red Sea-Dead Sea project,” Reuters, 2 February 2015.

“Jordan hopes controversial Red Sea Dead Sea project will stem water crisis,” The Guardian, 20 March 2014.

Photo courtesy of NASA/GSFC/Landsat