Fall 2016

The Hesitant U.S. Rescue of the Soviet Economy

– Diana Villiers Negroponte

As the Soviet Union crumbled, Mikhail Gorbachev sought foreign grants and loans to enable the transition to a free market economy. Only in December 1991, when he resigned and the Soviet Union morphed into 12 republics, did President George H.W. Bush send a major economic support package to Congress.

The refrain from a song in West Side Story rings in our ears as we review the first 18 months of George H. W. Bush’s administration: “Play it cool, boy, real cool.” The rapid disintegration of the Soviet empire, support for East German withdrawal from the Soviet bloc and its integration into NATO, dwindling Soviet support for national revolutionary movements in Central America, and the slow but steady support given to states seeking independence in the Baltics were all managed with firmness and caution. Throughout the Soviet retreat, there would be neither a victory parade nor any dancing on tanks. Any boasting risked hardliners in the Kremlin throwing out the reformist Mikhail Gorbachev as he sought to transform the Soviet economic and political systems through perestroika (restructuring) and glasnost (opening).

As in West Side Story, the ”Jets” faced the “Sharks” with intensity and knives as Secretary of State James A. Baker III held together a coalition of unlikely global partners to confront Saddam Hussein’s occupation of Kuwait. With Gorbachev’s acquiescence, Baker gained the overwhelming majority of the UN Security Council to use “all necessary means” should the Iraqis not withdraw of their own accord from Kuwait. Behind the discipline of a highly skilled domestic political operator, backed by foreign policy experts, lay remarkable drive to succeed. The United States could stabilize the international order and reign in the mavericks through careful diplomacy and the weight of American military might. Its economy, though weakened by a mild recession in 1990, remained stronger than those of its European partners and potential competitor Japan.

Why then did the United States not take the lead in supporting Gorbachev’s perestroika as he struggled to turn a command economy into a free market? USAID, supported by congressional appropriators, found $300 million to support Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia in the years 1989-91. Technical advice, credits, and seed money were given to enable these three countries to transform their economies and aspire to one day join the European Economic Community.

Said Baker, “All of us recognize that you cannot build a market economy by throwing money at a disintegrating command economy.”

However, the treatment of the Soviet Union was distinct. There was no grant money, no loans, only commercial credit guarantees for the purchase of American wheat benefiting Midwest farmers. National Security Adviser, retired general Brent Scowcroft described the Soviet economy as a “rat hole.” Baker did not respond to Gorbachev’s requests for credits to hold over the Soviet economy through 1990 and 1991. President Bush even rejected an invitation to the Soviet leader to appear at the London Summit of G7 leaders in July 1991, because he saw no practical Soviet plan to enact the economic reforms. With regard to supporting a transition to democracy and market economy, the US leadership played it cool. The German and French leaders considered the Bush administration to be obdurate and asked where was the leadership that had introduced the Marshall Plan and the economic revival of Europe after World War II. Until Gorbachev’s resignation in December 1991, no American grants or loans would help the Soviet leaders in their struggle to turn 70 years of communist totalitarian rule into a Western-styled socialist democracy.

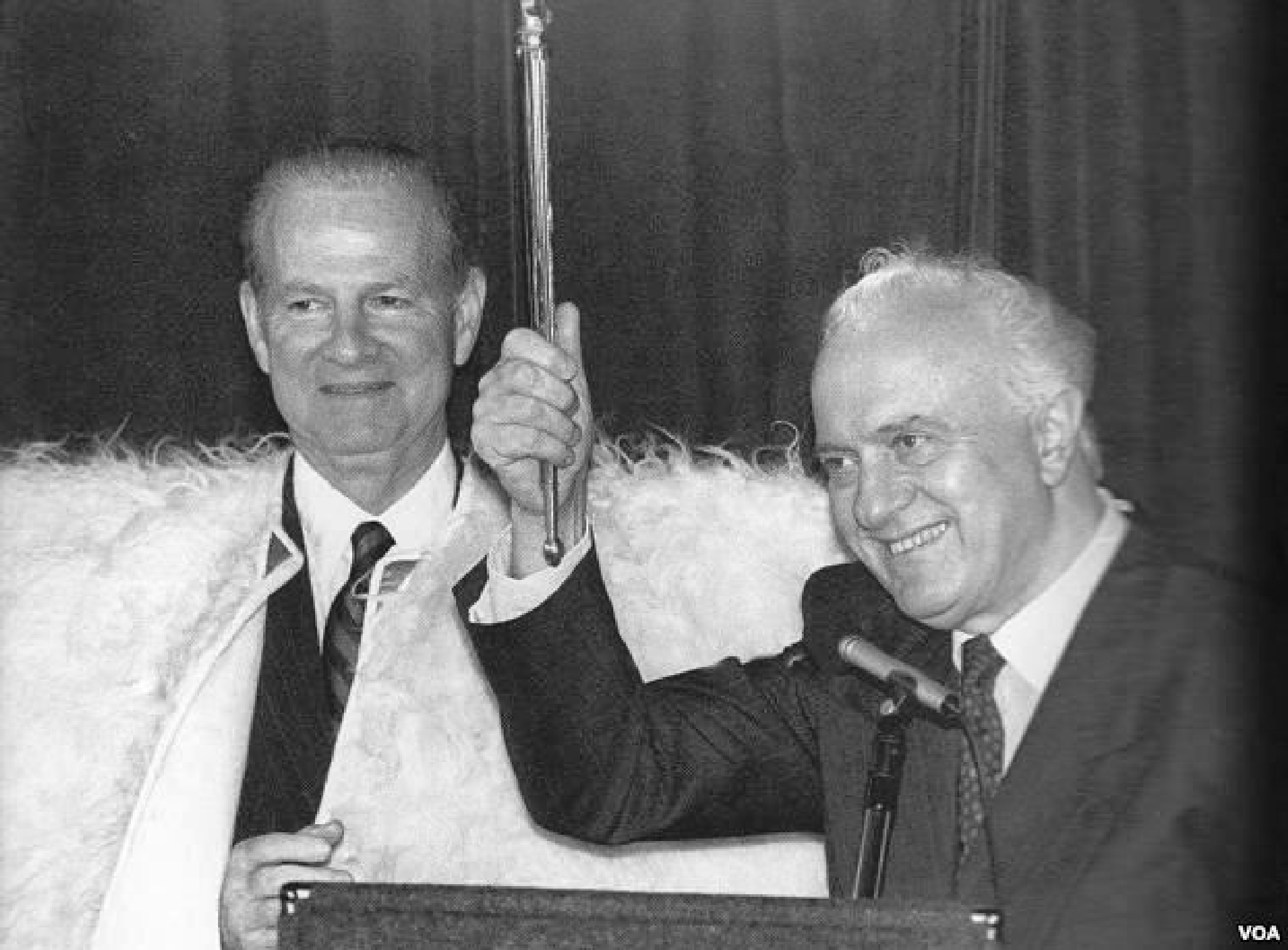

James Baker III Dialogue with Soviets

From his one-on-one talks with Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze as they flew westward to his ranch in Wyoming, Baker understood the consequences of a collapsing Soviet economy. That September 1989 marked the beginning of Baker’s dialogue with his Soviet counterpart and Gorbachev over the necessary reforms, beginning with convertibility of the currency and a free market made through supply and demand. Technical support — advisers and businessmen — to show them how to distribute food, develop their considerable energy resources to attract private investors, and convert military facilities into commercial centers for the production of consumer goods became the second most important topic, after arms control, in US/Soviet dialogues. In his discussions with Soviet leaders in Moscow and Washington, Baker talked about the necessary political and legal conditions for markets to flourish and attract private capital. He emphasized the need to introduce incentives, competition, prices, and a convertible currency, but he would give away no cash. Said Baker, “All of us recognize that you cannot build a market economy by throwing money at a disintegrating command economy.”

Gorbachev pleaded for grants and gained DM30 billion from Chancellor Helmut Kohl of Germany, but that money was soon spent and more was needed. Gorbachev came back to Kohl with a request for soap and coal, both precious consumer goods to help the Soviet people through the winter. In the winter of 1990, Shevardnadze pleaded with Western countries for $20 billion more to enable the reforms to begin. France, Italy, and Great Britain were sympathetic, but they looked to Washington for leadership. Baker had other problems on his mind as he waited for a Soviet economic plan that would demonstrate practical results.

The Grand Bargain

By November 1990, Professor Graham Allison of Harvard University had become alarmed at the deterioration of the Soviet economy. Partial reforms had allowed cooperatives to make and keep profits and raise salaries, but prices remained fixed to maintain social stability. Shortages resulted. Anticipating shortages of basic consumer goods, people began to hoard leather, cloth, winter coats, even soap. Store shelves were empty, and hoarding had became so habitual that doctors in Tadzhikistan claimed that children were suffering from serious allergies due to the quantity of soap stuffed in their homes. Cooperative managers were encouraged to make their own decisions for the profitability of their enterprise, but old-time government officials were not going to be left out of regulating production. Thus, private investors had to negotiate with both the cooperative managers and the government officials, often operating at cross-purposes. The reform of cooperatives was a failure, and economic chaos loomed.

The West had to be alert to the possibility that hungry, cold Soviet citizens struggling through another bitter winter could lead to chaos and the return of hardline Soviet leaders who would reject perestroika and glasnost.

Allison found a partner in Grigory Yavlinsky, a prominent reform-minded economist and close adviser to Shevardnadze. They collected together Soviet and Western economists to produce a Joint Plan for Economic Revitalization, otherwise known as the Window of Opportunity, the Grand Bargain. President Bush and Secretary Baker received their copy in June 1991, a month before the G7 meeting in London. The Grand Bargain reminded readers that the economic misery of Germany after World War 1 had led to rampant inflation and the emergence of the Weimar Republic. The West had to be alert to the possibility that hungry, cold Soviet citizens struggling through another bitter winter could lead to chaos and the return of hardline Soviet leaders who would reject perestroika and glasnost.

Allison and Yavlinsky argued that the United States should lead in the same way that President Truman and Secretary of State George Marshall had done in 1947: produce a Marshall Plan for the Soviet Union. In their analysis, a democratic transition would take place only if a stable economic transition was in place. The economic reforms, supported by Western funds, had to lead the process of political reform. Without that help, the political reforms were at risk.

Allison lobbied the Bush administration and the Congress. Members of the Democratic Party were sympathetic, and congressional hearings were held in which Allison and other supporters of Soviet aid made their case. But Bush and Baker continued to play it cool. They faced a seemingly unsolvable problem. Gorbachev insisted that he would carry out the recommended reforms after receiving Western aid with which to persuade reluctant Soviet citizens that life under economic reform would be better. Bush and Baker insisted that the reforms come first to prove that Gorbachev had the ability to carry out the changes, after which Western aid would flow.

By spring 1991 and despite the presence of technical advisers from the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, there still was no Soviet plan. Instead there were three plans, and the third one, Yevgeny Primakov’s plan, was nothing more than the central government’s management of a market economy. Washington was not impressed. Gorbachev had ignored IMF technical advice out of fear that the economic transformation would weaken his authority and ability to carry out the political reforms. For him, market prices meant higher prices. Privatization of cooperatives meant unemployment. Ending the construction of unoccupied buildings meant no jobs for construction workers.

G7 Meeting in London

When the seven major industrialized leaders met in July 1991, President Bush was under considerable pressure from Prime Minister John Major, President François Mitterand, and Chancellor Kohl to lead the rescue of the Soviet economy. All recognized that the Soviets were no longer creditworthy with $65 billion in outstanding debts; even German commercial bankers were reluctant to extend further credit to the Soviets. President Bush met the Europeans halfway. Technical assistance could enable the turnaround, but any cash now risked Gorbachev’s putting off the hard decisions that he had to make. Baker encouraged investment in the energy sector so as to earn hard currency and provide an example of a successful sector operating with property and contract rights. Military bases could be converted into civilian use. Food distribution could be made effective and efficient to provide goods for consumers through market incentives. However, beyond technical advice provided through the IMF and World Bank, the only US contribution was a significant $1.5 billion credit guarantee for the purchase of American wheat.

Instead, Baker asked others to cough up. He was happy to ask the Saudis, Kuwaitis, and Gulf States to support the Soviets with loans totaling $6 billion. He suggested that the German government might be willing to increase its financial support with a further DM12 billion to pay for the redeployment of Soviet troops, and he applauded the Japanese government for offering to extend $2.6 billion in credit with the expectation that it might regain control over the four disputed Kuril Islands.

Consequences of the Soviet Coup d’état

Only the coup d’état against Gorbachev in late August 1991 and the rise of Boris Yeltsin brought about change in the White House. Gorbachev overcame the plotters within his own Politburo, but he was seriously weakened. Those who had sought to return to the Leonid Brezhnev days had failed, bringing down the old communist system. Gradually, Bush and Baker recognized that Gorbachev was too wounded politically to hold the Soviet Union together. Yeltsin and the leaders of Ukraine, Byelorussia, and Kazakhstan were leading the breakup of the empire with dangerous consequences for economic management and the control of nuclear materials. No longer could the White House play it cool. What if Washington had to negotiate with 12 new nation-states over economic issues, defense matters, and arms control? Would each move toward a Western-style market economy, or would some retain their command economies? Bush and Baker had banked on Gorbachev’s enduring leadership, but in December 1991 they reluctantly concluded that his rule was over and a new Commonwealth of Independent States was emerging. The recently elected president of the Russian Republic, Boris Yeltsin, replaced Gorbachev on December 25, and a new US policy was needed.

The winter of 1991-92 awoke the American public’s attention. There were serious hunger and early signs of starvation in Armenia. Television footage of empty shelves and the haggard faces of elderly citizens alerted Americans to the downfall of their Cold War enemy. In a true spirit of American generosity and avoiding a victor’s jubilation, American citizens sought to help ordinary Russian citizens. Philanthropic organizations gathered clothes, medical supplies, and milk powder for people they had never known but now sought to help.

Project Hope, Americares, World Vision, and other US philanthropic organizations gathered needed supplies for suffering people, but they needed transport to deliver their gifts. The president committed $100 million to pay for US military transport, and 103 military flights delivered goods and people. Eight hundred American volunteers flew to Russia and the republics to teach efficient farming, food storage, and effective food distribution. In so doing, Americans met and befriended people whom they had previously considered the enemy.

Apart from facilitating the generosity of the American people, the federal government’s response was meager. Additional credit guarantees of $1.5 billion raised the amount of wheat that Russians could buy. Food aid totaling $165 million, including meals ready to eat left over from the Gulf War, were sent to Moscow and Leningrad, now renamed St. Petersburg. However, many of the boxes contained nothing more than paper cups and plates, and much of the fruit juice left from the war had turned rancid.

Growing Political Divisions

As 12 republics took the place of the Soviet Union, a US presidential election year began. Effects of the 1990 recession lingered, and the call for jobs in America was loud. In this context, a clear divide emerged. Conservative economists believed that the basic problem in Russia was the absence of property rights, a commercial code, and sound money, without which markets could not function. They maintained that US funds would be wasted or stolen or would dampen private sector growth by propping up the old bureaucracy. They favored sending technical advisers, opening Western markets to exports from the new republics, and helping the Russians dismantle their nuclear arsenal. Their advice was in keeping with the priorities of the Office of Management and Budget as well as the Treasury Department.

In their view, this aid was a bargain compared to the trillions of dollars that the US and Western Europe had spent on military defense against the Soviet threat in the Cold War.

On the other side were the liberal economists who believed that aid could buy both confidence and time for the reforms to work. They pointed to Korea in the 1950s, Europe after World War II, and Mexico at the start of the ’90s as examples of how foreign aid — tied to strict conditions — could play a positive economic role. Larry Summers, chief economist at the World Bank, and Stanley Fischer of MIT argued that $30 billion in financial assistance each year for several years was needed to sustain Russia and the other republics as they carried out the IMF reforms to privatize, marketize, and monetize their economies. In their view, this aid was a bargain compared to the trillions of dollars that the US and Western Europe had spent on military defense against the Soviet threat in the Cold War.

The divide played into party politics, with the White House and Republicans favoring conservative positions while Democrats favored the more liberal policies. Democratic congressman Richard Gephardt wrote that “US assistance and commercial presence in the Commonwealth of Independent States is negligible.” He argued for preferential trade status, exporting computers and telecommunications products as well as support for American business investment in Russia and the other republics. “Every day of delay endangers democratization and market development.…”

Freedom Support Act of 1992

In Russia, President Yeltsin struggled to carry out the economic reforms and introduce political pluralism while hardline opposition grew and threatened his tenure. In March 1992, the approval of $6 billion from the IMF to stabilize the ruble had gone some way to shore up Yeltsin and the Russian economy. However, the Russian Congress was due to meet in mid-April, and a majority was likely to rebuff Yeltsin and his reforms. Alarmed and faced with the likelihood of Yeltsin losing the vote, the White House sought Senate authorization for a package of measures to support the Russian economy.

Included in the Freedom Support Act of 1992 was $1.5 billion toward the IMF’s ruble stabilization fund; $2 billion to help plug Russia’s balance of payments; $600 million in humanitarian, technical, agricultural, and scientific research assistance; a further increase in guaranteed credits for the purchase of American wheat; and commercial loans to private US business seeking to invest in the former Soviet Union, known in Washington as the FSU. It also eliminated the various laws that restricted US trade with the former Soviet Union.

Related to funding for the FSU and Eastern Europe was a request for $12 billion to replenish the US contribution to the IMF. The proposed legislation was bold, but the likelihood of passing an aid package of this size before the November elections was very low. Baker tried, but he was a realist. Arkansas governor and presidential candidate Bill Clinton welcomed the package but joined others in criticizing the Bush administration for being overly cautious on the issue of aid to Russia.

A Washington observer noted, “Yeltsin’s over there trying to change the world, and we are saying, ‘Don’t bother me until November 4.’ ”

In Congress, there was little Republican interest in pushing forward a bill to support foreign aid for Russia and the former Soviet republics. With a presidential election seven months away, the secretary of state’s leverage to gain congressional support was squeezed. Within the Republican Party, former president Richard Nixon criticized the Russian aid measures as halfhearted, and presidential primary challenger Pat Buchanan called for less attention to foreign policy and more attention to the US economy. On the Democratic side, Senator Joe Biden was among the few supporting the aid package, and Bill Clinton accused President Bush of foot dragging on Russian aid. A Washington observer noted, “Yeltsin’s over there trying to change the world, and we are saying, ‘Don’t bother me until November 4.’ ”

Secretary Baker was approaching the time when he would leave the management of foreign affairs for the management of Bush’s reelection campaign. He knew that a second term would be needed to finish much of the foreign business he had begun. President Bush and his national security team had played it cool for too long. When they pulled out their knives to fight for major US economic assistance for Russia and the republics, it was late, and the demands of an electoral battle had replaced the urge to help former enemies.

* * *

Diana Villiers Negroponte is a Wilson Center public policy scholar. This article is a compressed version of a chapter from her forthcoming book, Master Negotiator: James A. Baker III’s Role at the End of the Cold War.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons