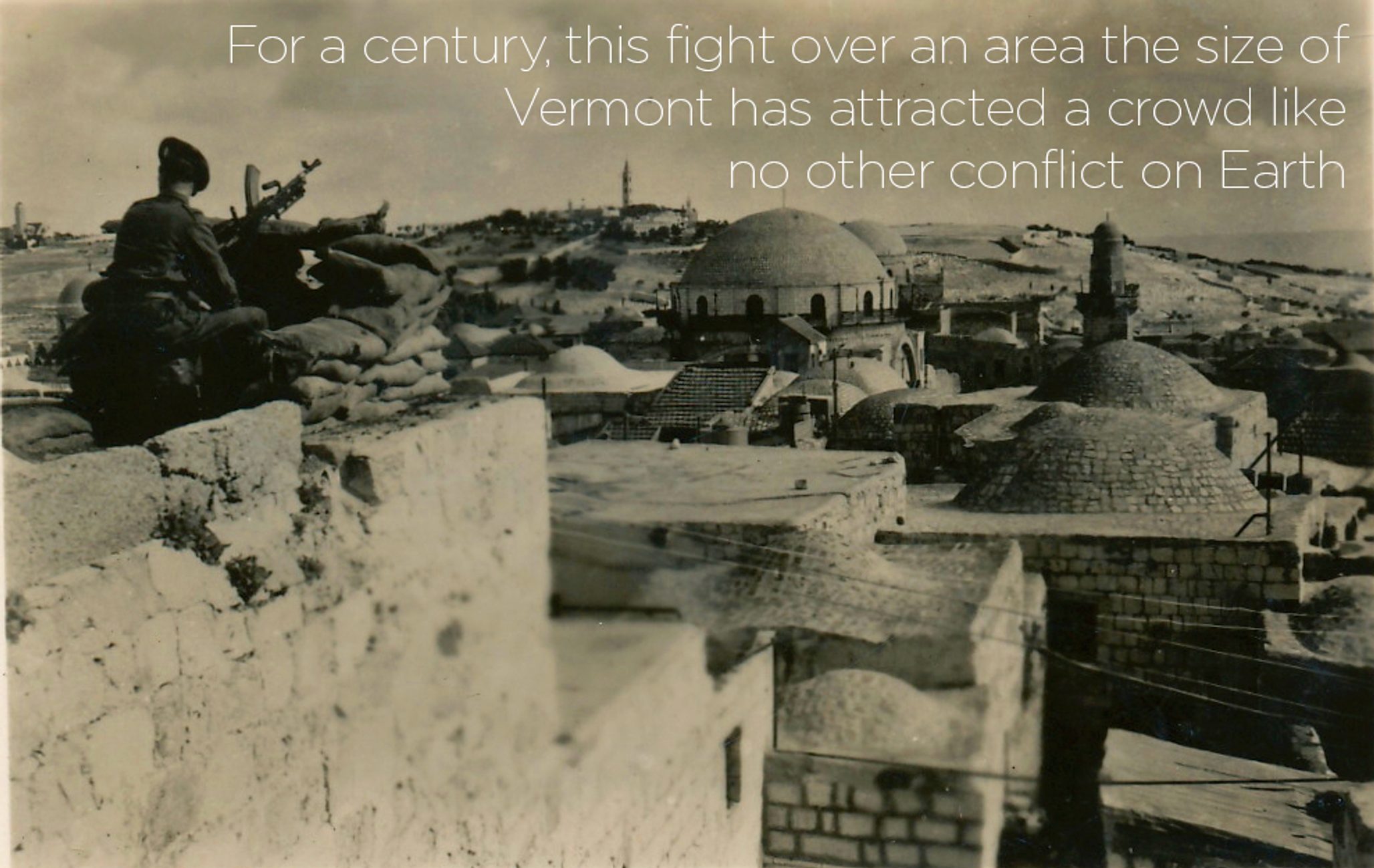

The Making of the Modern, Muddled, Middle East

– David Schoenbaum

Why and how the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is more equal than all the others.

Everything is very simple, said Carl von Clausewitz. But the simplest thing is difficult.

He was talking about war, but he could as easily have been talking about “The Eastern Question” — 19th century diplomatspeak for what to do about the Ottoman Empire. Or the geopolitical tangle Princeton historian L. Carl Brown would call “the most ‘penetrated’ diplomatic system in the world” 150 years later. Or the nation-state called Israel and the non-state nation called Palestine.

Whether as egg or as chicken, any one of them was practically guaranteed to lead to the other. Already on the skids by the time Clausewitz died in 1831, the Ottoman Empire would eventually disappear. The Gallipoli campaign, a century ago this year, helped it on its way. For the British, who had hoped to force the Straits come to the aid of their Russian ally and seize the Ottoman capital, it was a disaster. But it was a nation-building triumph for the Young Turks, whose primary concern was Turkey, not the empire.

What the war didn’t accomplish, the diplomats did. The first troops landed at Gallipoli on April 25. Six months later, Sir Henry McMahon, the British High Commissioner in Egypt, invited Hussein bin Ali, the Sharif of Mecca, to join the war against the Ottomans in return for Arab independence. In 1916, Sir Mark Sykes, a Tory baronet with a claim to Middle East expertise, and François-Georges Picot, a French diplomat from a colonial family, drew up a very different postwar map. Two years before the war ended, it divided the Ottoman Empire between Britain and France with minimal regard for the Arabs who actually lived there.

In November 1917, with eyes on Russia and America, Britain’s foreign secretary Arthur James Balfour assured the infant Zionist movement through a proxy that His Majesty’s government viewed “with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.” A few weeks later, Edmund Allenby, a British general, entered Jerusalem, accompanied by French, Italian, and American military attachés. He was received by guards representing England, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, Australia, New Zealand, India, France, and Italy. In 1922, the League of Nations awarded Britain a mandate to govern Palestine. It barely survived a generation.

In 1937, Britain’s Peel commission proposed partition of mandatory Palestine into a Jewish and an Arab state. A decade and another World War later, the United Nations General Assembly reaffirmed the proposal in Resolution 181. This time it was acted on. Israel declared its independence. The neighboring states declared intransigent opposition. Hostilities ended with a matched set of bilaterally negotiated armistice agreements. Pending a settlement that never came, an estimated 750,000 Palestinian Arabs took up residence elsewhere as refugees. Only Jordan offered them citizenship.

In 1967, the Security Council reaffirmed partition again in Resolution 242. In 1973, it reaffirmed it once more in Resolution 338. Though neither side was happy with it. Israelis said yes. Palestinians said no as they would again in 1979, 2000, and 2008. Abused and neglected by both sides, the Oslo Accords of 1993 withered and died on the threshold of the new century.

Yet it is also not true that nothing moves. In 2001, the Arab League’s Three Noes of 1967 — no peace, no recognition, no negotiations — gave way to an Arab peace initiative. DOA? There’s certainly a case to be made. But even after 14 years, Snow White awaiting her prince is at least worth a thought experiment. Cold though they may be, peace treaties with Egypt and Jordan remain in place. Palestinians, once extras in a movie produced in bickering Arab capitals now bicker for themselves, and at least intermittently with Israelis. “There were no such thing as Palestinians. … They did not exist,” Israel’s Prime Minister Golda Meir told The Sunday Times in 1969. Years have passed since Israelis last denied that Palestinians exist. Both Israeli and Palestinian majorities still accept the two-state principle, If only as the least bad option. Even Benjamin Netanyahu, who came out for two states in a much-quoted speech in 2009, declared that he was still for it after declaring against it on the eve of the March 2015 election.

Nearly a century after the passing of the Ottoman empire, its legacy and loss can still be seen and felt from the Mediterranean to the Khyber Pass. Since World War II, the region has done its bit to finish off the British and Soviet empires; turned the United States into history’s most reluctant Middle Eastern power, and upended at least two American presidencies.

Since 2001, alienated young Muslims have weaponized airliners, kidnapped Nigerian schoolgirls, devastated shrines from Timbuktu to the Hindu Kush, and declared war on presumptive non-believers (including fellow Muslims). Only recently, a corps of zealots recruited from many countries has dismayed much of the world with historical reminiscences and theological fantasies that even fellow Muslims denounce. The sophistication of its fundraising and money-laundering operations might shock and awe a Mexican drug lord, and its videos, as professional as they are horrific, enjoy real time attention exceeding anything Gavrilo Princip ever dreamed of.

Since 2003, Iraq has repeatedly stared into the abyss, Libya has imploded, Syria has disintegrated, and Egypt has exchanged a tired old military dictatorship for a fresh new military dictatorship. Lebanon has regained its default position as a civil war waiting to happen. After 13 years of American intervention, attention, and cascades of money, Afghanistan has advanced at best from a black hole to 50 shades of grey. Even Yemen, ordinarily as obscure as Paraguay, has become news fit to print.

Even as Iranian centrifuges continue to spin and wrecking balls of virtually every sort and size short of nuclear pound the house that Sykes and Picot built, the latest Israeli election, like the war in Gaza that preceded it, and the war in Lebanon that preceded that, only confirms what has been clear for more than half a century: The Palestine conflict can be relied on to draw a crowd like no other conflict on the planet.

To call it ‘unique’ is a generalization too far in a world where there are already enough national and territorial conflicts to go around. Sri Lanka, Cyprus, and Ireland show that even island conflicts have global potential. Both the construction and deconstruction of Yugoslavia set off shots heard round the world. India and Pakistan have gone to war four times since 1947, and the Kashmir conflict is still unresolved. Meanwhile, both parties have become nuclear powers. In 1982, Britain and Argentina went to war over the Falkland Islands, a territory with fewer than 3,000 people and a half-million sheep. Only recently, China and Japan approached the flashpoint over islands with no inhabitants at all.

Yet the conflict once known as Arab-Israeli (and now more accurately as Israeli-Palestinian) remains a phenomenon unto itself, as seemingly indestructible as it is seemingly insoluble, with media spin, novelists, and even dueling archaeologists regularly deployed as weapons of mass instruction.

In 2007, Israeli restoration of an access ramp to archaeological excavations under the Temple Mount drew protests from as far away as Malaysia. In April 2014, Saeb Erekat, a senior Palestinian official, took Martin Indyk, a senior American official, to Jericho, where time is measured in millennia. His message in the 47th year of Israeli occupation was substantially the same as Shelley’s in “Ozymandias,” a sonnet first published in 1818.

Winston Churchill famously defined the Soviet Union as “a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.” Translated into Churchillian, today’s Palestine conflict could be defined as a nationality clash wrapped in historical and religious claims to an area the size of Vermont, where local, regional and global concerns fit one within the other like a set of matryoshkas.

With or without Jews, Palestine is the territorial hinge between the Arab world of the Nile and the Arab world of the Fertile Crescent. From ancient to modern times, from Assyria to Egypt, Italy to China, Britain to India, it has stood astride the Silk Road, bridged the Red Sea and Mediterranean, and flanked Suez. Long before the age of Mohammad, Mecca was already a natural entrepôt and business center, not unlike Doha and Dubai today. For the next 1300 years, the isthmus of Suez was a canal waiting to happen. With or without Jews, Jerusalem has been a midpoint between Cairo, Damascus, and Baghdad; sacred to Jews since David, the city has been sacred to Christians since Jesus and Muslims since Mohammad. But invaders from Sennacherib and Nebuchadnezzar to Allenby and Abdullah never lacked for reasons to lay siege to it. Religion, rarely sufficient and often not even necessary, is only one of them.

Measured in millennia, today’s Palestine conflict is actually a relative youngster. Jews have never ceased to be a part of the Middle Eastern landscape, even though the last nominally independent Jewish kingdom capitulated to the Romans a few decades before the Common Era. From the middle of the 8th century to the end of the 15th, Jews, Muslims, and Christians coexisted in Spain. For centuries, Jews, Turks, and Arabs coexisted in the Ottoman empire. From the Romans to the Ottomans, Aleppo was a center of Jewish scholarship and commerce. In 1900, Jews comprised a quarter of the population of Baghdad. In 1948, there were an estimated 140,000-150,000 Jews in Iran.

Long forgotten, there might have been an exit ramp or at least an alternative scenario to what we now know as the Palestine conflict before it even began. In 1903, the British proposed the establishment of a “Jewish settlement or colony” in Uganda. The Zionist Congress, the movement’s governing body, voted 295-178 to dispatch a committee to look into the proposal. But it sank like a stone two years later when the group reconvened in Basle, and declared Palestine the only possible Jewish national home. The tug of war has been with us ever since.

Like geography, resources are a crucial part of the big picture. Cotton for the mills of Britain and France led to British foreclosure on a hopelessly indebted Egypt in 1882. Oil for Britain’s Royal Navy on the eve of World War I came next, with long-term consequences for Iran, the region, and the world economy. With coal’s steady retreat, the Middle East, with up to two-thirds of the planet’s known oil reserves, remains the world’s energy supplier.

Unsurprisingly, the geography that favored commerce also favors diversity within diversity; a maximum of e pluribus and a minimum of unum. At least a dozen local or imported languages are spoken daily in 18 countries by at least two dozen nationalities and ethnicities. It’s not for nothing that the tower of Babel is a formative myth. Irrespective of venue, archaeological museums confirm that armies — native and foreign, tribal and imperial — have criss-crossed the region, from Assyrians, Egyptians, Persians, and Greeks, to Napoleon, Rommel, Nasser, and Sharon. Benchmarks of regional history dot the landscape: the Western Wall in Jerusalem, the only survivor of the Second Temple; the Arch of Titus in Rome, commemorating the conquest of Jerusalem and the Temple’s destruction, stands as a victory lap in stone.

Religion, of course, adds still more faces to the geopolitical polygon. Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, the great monotheistic religions, share Middle Eastern roots and theological DNA. Though each established a global presence early in its millennial history, each has remained spiritually and physically attached to its regional roots.

Both in and beyond the region of their birth, these religions have inclined to conflict. Within a century of Mohammad’s death, Islam established itself from Spain to India, sometimes peacefully, sometimes not. His successors split irreversibly over the succession. For 200 years, West European crusaders, hellbent on hostile takeover of Christianity’s birthplace, inflicted mass mayhem on Jews and Muslims. From 1517 to 1648, European Christians turned their fratricidal attentions to one another while Ottoman armies advanced on Vienna. In the 1850s, Catholic French and Orthodox Russians insisted that each had a more legitimate claim to Jerusalem than the other. Their claims helped ignite the Crimean War.

In 1898, Germany’s Wilhelm II visited Jerusalem to dedicate the city’s second Protestant church. Before leaving, he received Theodor Herzl, who hoped the kaiser might lobby the Turkish sultan on behalf of infant Zionism. Instead, Wilhelm proclaimed himself protector of the Muslims en route home via Damascus. In the 1930s, for lack of secular alternatives, Palestinian Arabs looked to a cleric for leadership: Haj Amin al-Husseini, the deeply anti-Jewish, anti-British Grand Mufti of Jerusalem. Husseini, in turn, looked to Hitler’s Germany and spent the war years in Berlin.

Despite fond hopes, practical indifference or well-intentioned ignorance by the heirs of Sykes and Picot, Syria and Iraq are one more tutorial on what can happen in a political ecosystem where the secular nation-state remains the exception, and religious identity is a surrogate for national identity. In both countries, as well as Egypt, Christians are now an endangered species, while relations between Shi’a and Sunni, Iran and Saudi Arabia, increasingly recall early modern Europe’s Thirty Years War, with no Treaty of Westphalia in view at the end of the tunnel.

With 5 million people and 18 recognized religious communities, Lebanon alone is a walk-in tutorial on the facts of regional life. Beginning in 1975, sect battled sect and proxy battled proxy. Israelis arrived in 1982 to battle Palestinians in a joint venture with the Maronite Christians only reluctantly acknowledged by both sides. By 1990, when the war ended, the body count was estimated at five percent of Lebanon’s population. As an Israeli sergeant explains to his platoon in the 1986 film Richochets, Lebanon is a metaphor for the whole region: “everyone hates everyone, but they all hate us.”

Syria and Iraq are one more tutorial on what can happen in a political ecosystem where the secular nation-state remains the exception, and religious identity is a surrogate for national identity

Add oil, two world wars, and Cold War geopolitics to the regional mix. World War I gave Britain cause to seek clients among both Jews and Arabs. World War II produced the Shoah and gave the American military government in Germany cause to steer its survivors to Palestine despite deep ambivalence in Washington, let alone London. The Cold War gave the Soviet Union cause, in 1955, to sell arms to Egypt via Czechoslovakia. The Czech arms deal gave the United States cause to respond in kind, pushing ahead with plans for a kind of Middle Eastern NATO that included Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and even Pakistan. As usual, external concerns and local predilections turned the global local, and vice versa. The Middle East was now an accessory to the Cold War, and the Soviet Union an accessory to the Palestine conflict.

A year after the arms deal, Egypt’s decision to nationalize the Suez Canal led to war with Britain, and reminded an isolated Israel, exposed to attack from Gaza, that it was in serious need of friends. Short-term fallout included the loss of over 10 percent of world oil output (with obvious consequences for a Western Europe that relied on the Middle East for two-thirds of its oil) and the collapse of the pound sterling, still one of the world’s reserve currencies. Long-term consequences included an ever-larger American role and stake in an unfamiliar and accident-prone corner of the world, and an unacknowledged Israeli Bomb, which remains one of the world’s most public secrets.

A far more dramatic war in 1967 ended in six days. Israel’s stunning victory averted direct extra-regional intervention, but it left the West Bank a juridical white space, provisionally filled by an Israeli occupation still in place nearly a half-century later. It also emancipated Palestinians from the fraternal tutelage of their Arab neighbors, freeing them, for better or worse, to act on their own.

Three years later, emancipated Palestinians hijacked four international flights and attempted to overthrow the Kingdom of Jordan. When Syria came to support the Palestinians, Israel threatened to defend Jordan’s crown. When the Soviet Union threatened to support Syria, the United States threatened to support Israel. The Sixth Fleet and contingents at Fort Bragg and in Germany were reportedly at the ready before the passengers disembarked and the hijacked planes were blown up live on TV for viewers around the world to see. The plan was “to bring special attention to the Palestinian problem,” said a spokesperson. It did. But this time, the defeated Palestinians were forced to retreat to Lebanon.

In a 1973 sequel to the 1967 war, Egypt and Syria resumed their offensive with coordinated assaults on the Suez Canal and the Golan Heights, while the oil producers imposed an embargo on states they considered neutral or friendly to Israel. Shock waves from both the war and the boycott would be felt around the world for the rest of the decade. According to credible reports, by the second day of the war, things looked so dark that Israeli Defense Minister Moshe Dayan proposed a nuclear demonstration as a show of force. Prime Minister Golda Meir was unequivocally opposed. A few dramatic days later, the Soviet Union resupplied its clients. The U.S. not only did the same, it placed the Strategic Air Command, Continental Air Defense Command, European Command, and Sixth Fleet on DEFCON 3, the highest level of peacetime readiness.

Nuclear war didn’t materialize, but the Cold War proxy battles continued. Palestine was nowhere in view in 1979, when Soviet invasion of Afghanistan led to one of America’s most celebrated covert operations, a joint venture with Saudi Arabia and Pakistan in support of local resistance. But the Israeli-Palestinian issue did surface briefly in 1990, when Iraq’s Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait and threatened to rain rockets on Israel. The U.S. persuaded Israel to abstain in return for an American-manned umbrella of Patriot missiles while America mobilized a formidable alliance of European allies and Arabs. A few years of relative calm ended on September 11, 2001, when the horrific blowback from Afghanistan struck civilians on American soil while Israelis contended with a Palestinian eruption known as the Second Intifada. It came as no surprise that Israelis and Americans saw one another as natural allies in what was now known as the War on Terror.

It has been said that Jews are like everyone else, only more so. In the same sense, it could be said that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is like every other Middle East conflict, only more so.

In the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, two secular historical experiences superimposed a global morality play without historical precedent. One was the Nazi murder of some two-thirds of Europe’s Jews by the end of World War II. The other was the progressive decolonization of Asia and Africa, which began almost immediately after the war’s end. Both inevitably left their traces on the usual suspects in the usual capitals. Eager to get Britain out of the approaches to the Black Sea, the Russians were within minutes of being first to recognize Israel. Stalinist paranoia, traditional anti-Semitism, anti-colonial ideology and geopolitical strategy then led to recalculation and a fateful tilt to the Arabs. Eager to minimize external commitments and encourage anti-communist nationalism in the Arab capitals, the executive branch in Washington labored into the mid-1960s to keep Israel and the Zionist enterprise at arm’s length. Congress was reluctant to commit money, let alone weapons, but civil society was a natural constituency from the beginning.

As might be expected, the world’s largest surviving Jewish community was intensely interested, passionately involved, and increasingly influential. An established community, well represented in states rich in electoral votes, identified effortlessly with Israel as comrades and landsleit. Important, too, was a national narrative that made it easy for millions of non-Jewish Americans to look at Israel with its pioneers, its immigrants, and its embattled democracy, and see themselves. “We are both of pioneer stock,” President Lyndon B. Johnson told Israeli dinner guests at his Texas ranch in 1968. “We both admire the courage and resourcefulness of the citizen-soldier.”

The dynamic evolved as the Cold War matured. Henry Kissinger snickered behind his hand in 1970 when Golda Meir declared Richard Nixon a friend of the Jewish people. Yet by any conventional measure — beginning with arms transfers — he certainly qualified as a friend of Israel. Ever more engaged in the Middle East as the historic European powers receded and withdrew, successive U.S. administrations were increasingly inclined to invest money, arms, and diplomatic facetime. In part, the commitment was a down-payment on regional peace, with complementary shares for Egypt as well as Israel; in part, it was equity in what the Pentagon and CIA had come to see as a strategic asset.

Domestic support moved. If support for Israel tilted to the left, it moved ever further right as evangelical Christians discovered their inner Zion. Once-obligatory photo ops with yarmulkes and Ashkenazic comfort food gave way to strategically timed visits to Israel. Presidents, irrespective of party, showed up for the annual convention of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), the powerful American pro-Israel lobby. Israeli prime ministers addressed joint sessions of Congress — most recently at the invitation of a Republican Speaker of the House of Representatives without prior notice, let alone consultation with the White House. Right or left, right or wrong, what happened in and to Israel not only remained news fit to print, but reliable media material. Even in the sunset of the foreign correspondent, American media maintained nine bureaus in Jerusalem, compared to seven in Paris, seven in Berlin, seven in Rome — Jerusalem second only to the 13 bureaus in London.

Palestinians, too, had their storyline and constituency. Once the preserve of a handful of liberal journalists, East Coast establishmentarians, and so-called State Department Arabists, it would eventually include an ad hoc alliance of oil companies, Protestant denominations with missionary pasts, aging New Leftists, and, after the 2014 Gaza invasion, an actual majority of American 18-to-29-year-olds.

Polls revealed increasing differentials on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict by gender, race, and party affiliation. Two-thirds of self-identified Republicans tilt toward Israel; pluralities and near-majorities of women and non-whites tilted toward the Palestinians, but the aggregates remain virtually constant. Between 1988 and 2014, American sympathy for Israel fluctuated from under 40 to over 60 percent, but remained high and virtually constant between the Second Intifada in 2002 and the latest invasion of Gaza, while sympathy for Palestinians failed to surpass 18 percent.

Shlomo Ben-Ami, a former Israeli diplomat, has astutely observed that Europe, where a Jewish complex coexists with a colonial complex, is different from the United States. A 2007 survey by the Anti-Defamation League found that in Europe, there was no popular majority for either side in the conflict: a plurality of Europeans leaned towards neutrality. Yet this neutrality was disinterested in only the technical sense: Sympathy for Israel, once taken more or less as a given, tends increasingly to the pro forma. Differentiation of anti-Zionism from anti-Semitism is obligatory, but as Ian Buruma and others have pointed out, not always convincing.

Both anti-Israel and anti-Muslim leanings have meanwhile taken alternately right-wing and left-wing forms. At least politically, some of Israel’s most voluble partisans descend from grandparents and great-grandparents who were anti-Dreyfusards or voted for Hitler. Palestinian sympathies are now found among one time '68ers and their intellectual progeny, as well as in growing (and increasingly activist) communities of immigrants from North Africa, the Middle East, and Pakistan. Survey data confirm that Europeans, too, follow news from the Middle East with regularity and concern; they also show, at least subliminally, how they wish it would go away. They are hardly alone in this.

In 1951, after a tour as America’s first ambassador to Israel, James G. McDonald wrote that the country’s future would be as a sort of Middle Eastern Switzerland, neither martial nor messianic. He has a modern-day echo, perhaps, in celebrated Israeli novelist Amos Oz, who last year told Deutsche Welle that his “hope and prayer” is “to see Israel removed once and for all from the front pages of all the newspapers in the world, and instead conquer, occupy, and build settlements in the literary, arts, music and architecture supplements.”

Churchill reportedly said of the Balkans that they “produce more history than they can consume.” The same can be said of the Middle East, where miracles, once widely reported, are now uncommon.

There is, at least, agreement that no news would be good news. But news remains a major export, and no one expects Israel to be confused with Switzerland anytime soon.

* * *

David Schoenbaum is the author of The United States and the State of Israel and a former scholar at the Wilson Center. Edited by Zack Stanton.

Cover image courtesy of Vimeo