Spring 2017

Trump Finds Support in Britain’s Brexit Capital

– Caitlin Randall

The anger and resentment that helped elect President Trump in the United States finds a mirror image in the heart of small-town Britain.

When Mick Harold woke up on November 9, 2016 to the news that Donald Trump had been elected president of the United States, he punched the air in silent celebration.

“I had a good wager on Trump, a couple of hundred pounds at 8-to-1 odds,” says the 55-year-old politician from Stoke-on-Trent. His city is nicknamed Britain’s “Brexit capital,” as nearly 70 percent of residents who participated in the June 2016 European Union (EU) referendum voted for Britain to leave the bloc. “It’s hard to stand out from a crowd when they’re all baying at you. It takes bottle to knock the establishment. Trump and Farage have it, and people responded.”

Harold, who chairs the anti-immigration UK Independence Party (UKIP) in Stoke Central, credits long-time party leader Nigel Farage with helping Donald Trump press his case to the American people. In the days just after U.S. election, while much of the world was still absorbing the shock, Trump rewarded Farage for his loyalty. Invited to Trump Tower, the UKIP founder was the first foreign politician to meet the president-elect. The former commodities trader could hardly contain himself, gleefully tweeting a photo of the occasion: both men, puffed up and beaming, are standing shoulder-to-shoulder before a set of gilded doors. Later, Farage, barnstorming before the Conservative Political Action Conference, would claim Trump’s victory and Brexit as “the beginning of a great global revolution.”

Like Trump, Farage, who spearheaded the campaign to take Britain out of the EU, has championed his own home-grown populist revolt. He has called on voters to buck “global corporatism,” uncontrolled immigration, and the neoliberal ruling elite. And while the blustering right-winger is hardly a popular politician in Britain — he has lost seven elections to become a member of Parliament — like Trump, he has successfully tapped into portion of the voting public that feels a growing sense of alienation from the political class.

Most Britons do not like Donald Trump. Poll numbers are clear: 70 percent say they have an unfavorable opinion of the new president, with 56 percent holding a very unfavorable view, according to YouGov polling data. As in the United States, anger over Trump’s election quickly spilled into the streets. On the first day of his presidency, in the cold mist of a January morning in London, banners were unfurled from bridges across the capital. “Build Bridges, Not Walls,” read one draped from the city’s landmark Tower Bridge. Another banner outside Parliament declared “Migrants welcome here.” The message was evident: Trump’s threats about immigration had no support in Britain.

Nearly two million people have signed a petition to stop the new president from making a state visit.

That weekend, in solidarity with the Women’s March in the United States, some 100,000 anti-Trump protestors thronged London’s streets. Since then, nearly two million people have signed a petition to stop the new president from making a state visit to the United Kingdom. Prime Minster Theresa May’s government, which is eagerly seeking a post-Brexit trade deal with the United States, is adamant that President Trump will come to England. Indeed, plans are afoot for the visit to take place in October, when Parliament is not in session — thereby avoiding the spectacle of an address before protesting MPs. Anti-Trump activists in Britain also have plans of their own. In a statement, the UK-wide Stop Trump Coalition promised: “The opposition to this state visit, and to Trump’s policies, is growing every day. Whether he comes in spring or autumn, or to London, Birmingham or Scotland, we will meet him in huge numbers to say that the politics of hate and prejudice are not welcome here.”

But Britain, like the United States, is a deeply divided nation.

To get a sense of England’s political schism, go to Stoke-on-Trent, which sits between Manchester and Birmingham in the country’s hard-pressed north. The shadow of its lost industrial past hangs over this small-scale city, where boarded buildings and abandoned factories dot the urban landscape. Haunted by the decline of its manufacturing core, including the once-famous pottery industry — at the peak of its productivity, local workers kiln-fired millions of colorful plates, tiles, and bowls to sell in fine ceramic shops around the world — Stoke is now a hotbed of working-class disaffection.

“There’s a portion of the population who feel they have no voice, who feel alienated from politics, and feel their views are being excluded from the political agenda,” says Mick Temple, a professor of journalism and politics at Staffordshire University in Stoke.

In February, Stoke voters went to the polls to fill a vacant parliamentary seat, a by-election hyped as a moment of truth for UKIP and Britain’s left-leaning Labour Party, alike. The Conservative party, which holds a majority in government, had only a minor role in the political calculus here. Stoke-on-Trent has been a Labour stronghold since the constituency was created in 1950, and a loss here would have shaken a party already suffering nationally from historically poor polling figures. A win by UKIP, which hoped to capitalize on its support for last year’s Brexit referendum, would have given the small party a second member of Parliament.

On the day of the crunch election, gale-force winds and driving rains battered northern England. Voter turnout was discouragingly low, and the Labour candidate squeaked into office with 37 percent of the vote. The UKIP candidate, the party’s current leader, Paul Nuttall, dogged by controversy and perceived as an outsider, managed to increase UKIP’s vote count from its standing in the 2015 general election, but still failed to win the day.

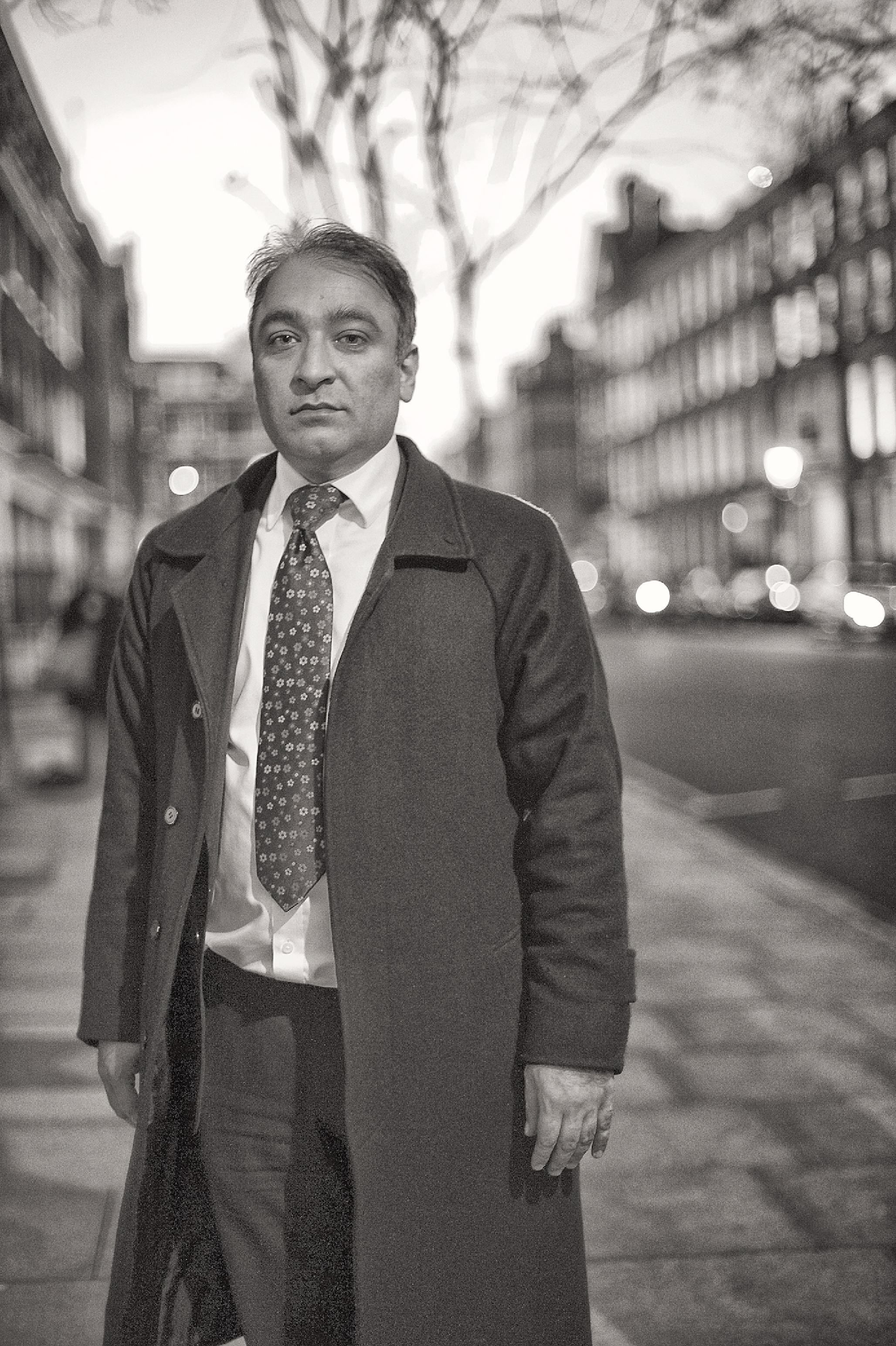

“We should have had a local candidate. There was a general concern and resentment that Paul was parachuted in to run for parliament,” says Tariq Mahmood, a barrister, practicing Muslim and the son of Pakistani immigrants — an unusual pedigree for a UKIP activist.

Mahmood had left the Labour Party to run as UKIP’s Stoke-on-Trent South parliamentary candidate in 2015. He denied that UKIP’s road to parliament looks rockier than ever, noting that in 2017, his party had cut further into Labour’s vote share, which had dwindled by half.

Temple sees UKIP’s blunt, often simplistic message as the kind of populist rhetoric that is winning over working-class communities.

“It was Paul Nuttall’s to lose,” counters Mick Temple of Staffordshire University, arguing that the UKIP candidate’s message to the working class was diluted by a series of “lies, fabrications, and fantasy” peddled in weeks of intense campaigning. But Temple sees UKIP’s blunt, often simplistic message as the kind of populist rhetoric that is winning over working-class communities. “Industry here — steel, coal, and potteries — was decimated in the 1980s,” he adds, noting that Stoke is still plagued by poor job prospects, low pay, and government budget cuts that have squeezed social services like health and education. A breakdown of Stoke’s demographics shows that 6.2 percent of adults in Stoke Central claim unemployment benefits, almost double the national average of 3.8 percent.

“It’s a similar core audience as Trump’s,” Temple says. “In America, it’s disaffected Republicans and a white working class that was previously largely apathetic about politics. Here,t’s former Labour voters who are driven by resentment towards the traditional elites and the parties in power.”

In the North Staffordshire YMCA, the community café is buzzing. It’s the first Friday of the month and the center offers locals a free meal and a chance to mingle. Danny Flynn, the local YMCA’s chief executive officer, bobs from table to table in the crowded hall. Flynn started his working life at 16 as an apprentice diesel-fitter not far from Stoke. Now 52, he still carries that experience with him, falling into easy conversation with factory workers, unemployed laborers, and teenage runaways. He’s clued in to this working-class area in a way that many politicians would envy.

“The pottery industry in Stoke-on-Trent in the 1988 employed 60,000 people. Now 6,000 work in the industry. That’s a 90 percent attrition rate,” says Flynn. Traditionally, he argues, working people would not hesitate to back Labour, but have increasingly turned to rightist populism for solutions.

“Labour supporters under [Party leader Jeremy] Corbyn are seen as fiercely ideological, and part of the educated, London elite that doesn’t speak for working-class communities,” Flynn says. “It’s a portion of the population that feels that for years and years, the government, the parties, and the institutions have abandoned them.”

Despite the derelict mills and boarded storefronts, there are sparks of hope in Stoke. Staffordshire University has a student body of 15,000, and what’s left of the city’s potteries has seen a small resurgence, with manufacturers like Emma Bridgewater even thriving. Ironically, in a city that voted by 66 percent to leave the EU, an end to tariff-free access to the single market may hit hard. And there is also the worry that the Stoke and Staffordshire region is set to lose £157 million in EU-allocated regeneration funding in the wake of last year’s referendum.

If there is a single issue that divides Britain, it is Brexit. The big cities in Britain chose one future; the rest of the country, another. That rupture closely echoes the results of the U.S. presidential election: a gulf between cities that are disproportionally made up of the young, educated, and multicultural, versus non-urban communities that are aging and largely white, and have a workforce that has been left behind by a changing economy.

In Britain, immigration has become the biggest scapegoat for all the country’s challenges.

In Britain, immigration has become the biggest scapegoat for all the country’s challenges. Brexit voters ranked immigration at the top of their list of concerns. “Take back control of our borders” was the chant, and those views have had an outsized impact on British politics. Echoing Trump’s incendiary campaign rhetoric about walling off Mexico, Farage set off a firestorm in the closing weeks of the Brexit campaign when he unveiled a billboard showing a desperate line of mostly non-white refugees trying to reach Europe under the tagline “Breaking Point: The EU Has Failed Us All.”

The county of Essex, just north of London on England’s eastern seacoast, facing mainland Europe, is UKIP’s heartland. The party’s only current MP, Douglas Carswell, won a parliamentary seat here. Every district in the county voted to leave the EU, with 62 percent overall opting for Brexit. And while only 3 percent of the population of Essex is registered as immigrants, the general view here is that uncontrolled immigration is at the root of Britain’s troubles.

“The problem for us is that we see our way of life disappearing,” says Alan Bayley, one of six UKIP Essex County councillors. Bayley argues that social services, from the National Health Service to police protection, have been strained to the breaking point by an influx of economic migrants to Britain, mostly from Eastern Europe. His neighbors from Castle Point and nearby Canvey Island — the self-proclaimed “most British place in Britain” — are quick to agree, despite a local population that is 95 percent white British. UKIP has gained traction here, primarily because of its stand on immigration.

Canvey Island in south Essex is separated from the mainland by a network of creeks that feed into the Thames estuary. A once lush expanse of marsh is now marred by housing estates, shuttered oil refineries, and electric pylons that march across the flatlands. Nearby, in a busy shopping district that is more strip mall than town center, locals chat outside the Sunshine Launderette.

Len, who is 52, is happy to discuss immigration on both sides of the Atlantic. “We have to do something about immigration,” he says gruffly. “It’s the same in America. I’m not saying Trump should build his wall, but he’s got the right idea to hold the line on who is coming in.” His views reflect a recent YouGov finding that Trump’s migrant ban holds some appeal here, with 29 percent of British respondents backing it.

Chris, a 58-year-old grandmother, chimes in. “The wall is a load of rubbish. Trump’s a fake and all his talk is just playing to the crowds,” she says, but defends Farage as “honest.” Carswell, whose Clacton constituency is just up the coast, is viewed with suspicion. “I’m not convinced he really supports Brexit,” says 51-year-old Gary, a local builder.

In a small conference room in Portcullis House, a bulky Thames-side parliamentary office building distinguished by its rows of tall, stylized chimneys, Douglas Carswell bounces into the room. He’s late, running from a meeting with his publishers, and eager to discuss big ideas — the death of liberal politics and the rise of “alt-right” radicalism — ignoring the internecine squabbles in UKIP that have lately grabbed the eye of the British press. A Conservative Party defector who joined UKIP in 2014, he has been tagged a “Tory posh boy” by Farage, who demanded that he be expelled from UKIP for not talking tough on immigration. Adding fuel to that fire are reports that Carswell may have sabotaged Farage’s secret campaign for a knighthood.*

“I’m much more interested in talking about your great republic than my career,” he says, struggling to relax into a straight-backed wooden chair.

Carswell is 46, with a long, oval face, jutting jaw, and lopsided grin. The son of two doctors, he lived in Uganda until his teens, when he was sent to Charterhouse, one of Britain’s oldest boarding schools. His view of the new American president is mixed. “I was bemused, somewhat confused, perplexed, but also slightly delighted at his election,” he says. But as the confusion of Trump’s first few weeks mount, along with an alarming number of bombshell Tweets, he wonders “if Trump’s critics were right after all.”

“Trump is no American Caesar about to cross some sort of Constitutional Rubicon,” he says.

A professed libertarian, Carswell argues that Trump’s election, like Brexit, was a phenomenon destined to occur. “The death of the center-left is a phenomenon that is happening throughout the Western world,” he says, arguing that a “technocratic, managerialist cadre of politicians” at the top of the leading parties in both Britain and the United States have “incubated the conditions that have allowed this alt-right, anti-politics, anti-establishment backlash” to occur.

On Brexit, Carswell insists that immigration was not the primary motivation, calling it “a shorthand” way of expressing a profound sense of lost control.

On Brexit, Carswell insists that immigration was not the primary motivation, calling it “a shorthand” way of expressing a profound sense of lost control. “If you deconstruct the objection to immigration, it’s not the number of foreigners in the country; it’s the fact that people can’t get into a [doctor’s office] to see a GP on a Saturday, which ends up the fault of a glutted health care system.”

Farage and a hefty number of UKIP supporters would likely disagree. Speaking to a radio station in Jackson, Mississippi in the months leading up to the U.S. election, Farage argued that immigration played a pivotal role in the Brexit campaign, a strategy he said that would help propel Trump into the White House. “Gradually,” Farage told listeners on SuperTalk FM, “people saw their way of life was changing, their quality of life deteriorating, and they kept being told by their leaders, ‘Oh, don’t worry about it, because our GDP is going up, so all immigration must be a good thing’…but who’s benefiting? It’s the big businesses getting cheap labor who are benefitting.”

Farage’s harsh rhetoric poisoned the debate on immigration, according to Staffordshire University’s Mick Temple, while the Labour Party “demonized” any legitimate worries that working-class voters may have had about the influx of economic migrants into Britain, quickly dismissing it as racism.

In the U.S. context, Nolan McCarty, a political scientist at Princeton, offers a similar argument. In an interview with New York Times columnist Thomas B. Edsell, McCarty concludes, “The Democrats have played immigration badly… They... (have been) deaf to concerns that many voters have about the effects of immigration on wages and public services… The Democrats have to do better than dismiss all opposition to immigration as racism.”

If Britain’s Labour Party and the U.S. Democratic Party are to reconnect with the hearts and souls of their constituencies, they will need to try to understand, not shame, the swathe of voters in both countries who feel left out of the prosperity that has prevailed in many metropolitan centers. If the Left hopes to upend right-wing populism, it first needs to address the movement’s roots.

* * *

*On March 25, UKIP MP Douglas Carswell resigned from his party, declaring he would continue in Parliament as an independent. He said he left UKIP “amicably” and in the knowledge that “we won," referring to Brexit. UKIP grandees were furious at the the news. In late April, Prime Minister Teresa May called a national election. Carswell has since announced he will stand down in the June 8 election and vote Conservative.

* * *

Caitlin Randall is a London-based freelance writer who has worked as a staff reporter for Reuters and Dow Jones Newswires and written for a wide variety of newspapers and magazines.

Cover photo courtesy of Peter Crabtree