Fall 2016

Walking in Each Other’s Shoes, Through the Iron Curtain and Back

– Izabella Tabarovsky

July 2017 marks exactly 40 years since the Photography USA exhibit came to my hometown of Novosibirsk, in what was then the USSR. It was part of one of the most successful hearts-and-minds campaigns the United States has ever undertaken.

In my Siberian hometown of Novosibirsk, the chances of walking out onto the street in 1977 and running into a living, breathing American were virtually nil. The Soviet Union, which would start to unravel a short eight years later, seemed as solid as ever. Barely a generation separated the country from the peak of an orgy of mass repressions. While society was starting to open up, fear still hung in the air.

And yet, a group of some thirty Americans came to my hometown that summer. They were guides and professional staff of the Photography USA exhibit, one of many such exhibits put together by the United States Information Agency (USIA) in the decades after the 1958 Lacy-Zarubin Agreement on exchanges in culture, science, and education between the United States and the USSR. For a full five weeks, they walked the streets of the city in the open, and they could be touched and talked to. It was even possible to invite them over to dinner at your apartment, and if you did, they would likely have accepted the invitation.

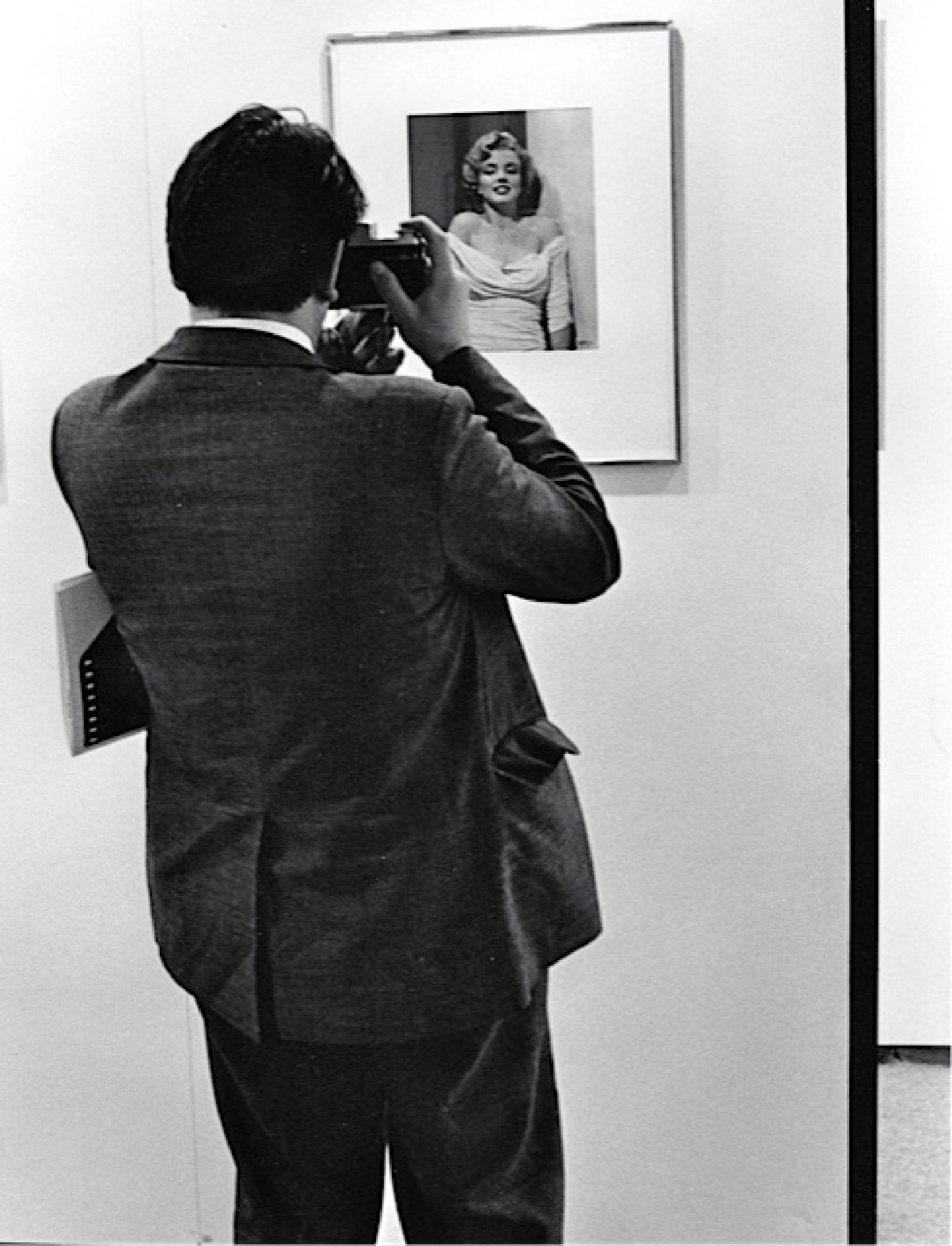

Undoubtedly, the exhibit had much to offer. Inside the giant geodesic dome that the Americans had set up in the center of the city were more than 400 prints by some of the most influential American photographers of the day, from Irving Penn to Mary Ellen Mark to Flip Schulke. The Polaroid Corporation set up a stand where American photographers could photograph Soviet visitors and produce prints in seconds. They even built a darkroom with a special glass wall that allowed visitors to watch the American staff develop the photographs.

In the visually austere Soviet environment, the images lining the walls aimed to fascinate and impress. The latest achievements in American photographic technology were on display, as well as a variety of subjects, including underwater fashion photography, time-delayed shots of a flying bullet, and artistic semi-nudes that would have raised the hackles of a Soviet censor.

No question was off limits, from the most innocently ignorant (“Do American cows have false teeth?” “Is it true that American women can have a child in five months?”) to the utterly hostile (“Why are you bombing our sailors in Vietnam?” “Why do you kill black people?”).

Still, none of these compared to the most fascinating exhibit of all: the guides who accompanied the show. It was these young, friendly, outgoing Americans, who day in and day out demonstrated the equipment and answered Soviet visitors’ eager questions, who were the primary attraction. No question was off limits, from the most innocently ignorant (“Do American cows have false teeth?” “Is it true that American women can have a child in five months?”) to the utterly hostile (“Why are you bombing our sailors in Vietnam?” “Why do you kill black people?”).

Craving Human Contact

By the time Photography USA arrived in Novosibirsk, USIA had been sending exhibits to the Soviet Union for nearly 20 years. The first exhibit coincided with Nixon’s 1959 visit to Moscow. It was here, at the American National Exhibition in Sokolniki, that the famous Nixon-Khrushchev kitchen debate took place. It was then that the USIA officials took note just how wildly popular the Russian-speaking American guides were.

The exhibit program that developed over the years was elaborate, well-organized, and well-funded. From 1959 to 1989, USIA put together 19 exhibits that touched on a wide range of topics, from American leisure to education, from architecture and design to American technology in the home. The exhibits traveled to two dozen Soviet cities in total. Toward the end of the program, one former USIA official estimated, it cost some $20 million to put an exhibit together, ship it overseas, and show it on a typical six-city tour.

In all, over 17 million Soviet people are estimated to have seen the exhibits, and the impressions of each lingered and reverberated. People held on to the brochures and pins from each one, passing them on to others. Some 30 years after his work as a guide with Photography USA, John Beyrle, who went on to become U.S. ambassador to Russia, discovered that some of the people who had attended the exhibit still had those brochures. Hundreds of people must have read each copy, he told me. Today, there are chat rooms on the Internet where Russians still talk about the impact the exhibit had on them. They can still remember and accurately describe the images they saw.

As much as technology and other display items served as a point of interest, it is fair to say that it was human contact that people craved the most and that left the deepest impression. Isolated from the rest of the world, Soviet people wanted to know what life was like on the other side of the Iron Curtain. With their questions, they tested every one of the assumptions, shaped by Soviet propaganda, that they held about the United States. But more than anything, they wanted to satisfy the basic human urge to get to know another person, to swap life stories with a stranger, to learn about others’ experiences, and make new friends.

As much as technology and other display items served as a point of interest, it is fair to say that it was human contact that people craved the most and that left the deepest impression.

The Mystery

What happens when you first meet a person whom you had always been told was your enemy? At what point do you realize that standing in front of you is simply another human being? Staring at each other across the symbolic divides of the exhibition space — Americans on platforms, the clamorous crowds surrounding them — each side had to set aside their stereotypes. Confronted with one another, both sides were forced to replace the propaganda images they carried with images of real life and allow themselves to be affected by the truth of what they saw.

In that encounter, there was mystery. Both sides saw the other as exotic and enchanting, though for entirely different reasons. Young Americans were fascinated by the austere environment of Soviet cities, where the only commercial signs on the buildings were the generic “Meat,” “Bread,” and “Fabrics.” Some were charmed by the decaying chic of the Moscow Metropol Hotel and the legendary poor service in Soviet restaurants. The red-lettered “exhortations” on the buildings urging Soviet citizens toward greater socialist achievements left a lasting impression on others.

Many Soviets visitors to the exhibits, on the other hand, were fascinated by the fact that the female guides, most of whom were in their 20s, were not married and did not have children. In a country obsessed with the nationality question since the 1917 revolution, they endlessly probed the guides’ ethnic origins. Some guides recalled that saying they were American was not enough. Their interlocutors wanted to get to the roots of their heritage, to decipher the meaning of a guide’s dark curls or “oriental” facial features.

The crowds were not always friendly. Agitators abounded, rehearsing staples of Soviet propaganda regarding high medical costs, unemployment, and racial tensions in the United States and pushing the guides to the wall with hostile and unrelenting questioning. “Why does the United States support the racist regime of South Africa?” “Why do you have so much crime in America?” “Is it true that people are afraid to go outside at night?” “Why does your president say we don’t have human rights? What rights is he talking about?” “Why does the United States have military bases around the world? We don’t have any outside our own borders.” “You say Communists aren’t persecuted in the United States. What about Angela Davis?” Some of the questioners were so relentless that they brought a number of guides to tears.

Thrown into this experience, and largely left to sink or swim, the guides quickly learned to work the crowds. “When you were on the ropes, when the agitators had the upper hand and were dominating the conversation, you would look around in the crowd for people who could be potential sympathetic voices,” John Beyrle told me. “You could almost feel, by looking at their faces, who was unhappy that you were being subjected to a grilling by these agitators. Maybe they wouldn’t jump to your defense, but if you appealed to them and said, ‘I’m a guest in your country! Is this how you treat your guests?’ — that was immediately an opening for someone else to say, ‘Enough of that, I’d like to ask about something else.’” Questions about life in America often followed, prompted by simple curiosity about family, education, and the cost of living in another country.

Representing Themselves

I, too, had a question that I posed repeatedly to the guides. I wanted to know whether they received some special training from intelligence services before they traveled to enemy territory. Did someone take them to some CIA bunker and brief them on how to handle conversations with the Soviets? Were they told what to say? Didn’t they at least have talking points: if they ask you this, you say that; if they ask you that, you pivot in this direction?

I eventually had to believe what the guides were telling me. To be sure, they were supposed to have conversational Russian skills and know basic facts about the United States to share with the visitors. What was far more important for USIA officials, though, was that the guides had good communication skills and could represent themselves. In USIA’s eyes, these young kids, with their individuality, their own political views (and lack of fear in expressing them), their own cultural preferences, and their own perspectives were America’s greatest product — one that stood in great contrast to the imposed uniformity of thought in the Soviet Union.

This decision proved prescient. Most of the guides were young college graduates, largely liberal in their political views, and they did not hold back from strongly criticizing their government and its foreign policy — especially with respect to the Vietnam War. The fact that employees of the American government could do so and still be back at work the next day was a source of great surprise and confusion for the Soviet visitors. In a country where conformity was a matter of survival, this freedom of expression told vastly more about America than anything else at the exhibit could.

While the visitors largely shied away from political conversations in public spaces, they reciprocated in other ways. The guides had more invitations to dinners, dachas, and social events than they could handle. They were given gifts — usually items of little monetary value but of tremendous personal significance. And they reveled in long, soulful conversations with their Russian friends that went on deep into the night. In Russia, they found a different model of relating and valuing life’s experiences. Many remarked on the profound significance of friendship in Russia.

And so, as much as Americans opened the eyes of Soviet visitors to a new world, the guides, too, found that the encounters forced them to grow up and confront their own preconceived notions. In the Soviet Union, they were surprised to find a society that was less uniform than they had expected. They found that the experience made them more independent thinkers, or forced them to realize they had been living in a bubble. “I’d thought they would all hate us, that we were enemies, but the vast majority of people did not relate to us that way. To realize that they were very warm and welcoming to us was life-changing for me,” Roland Merullo told me.

Like astronauts returning from space, many came back to the United States unable to explain what they had seen over there, on the other side. After all, America had a propaganda of its own that shaped views and attitudes. The notion that there, on the other side of the divide, were real human beings who bore little hostility toward ordinary Americans, did not square with accepted wisdom. And so, like soldiers who bond in the crucible of a tough experience, many of the guides stuck together, maintaining lifelong friendships and even marrying one another. And they kept going back for more.

Like astronauts returning from space, many came back to the United States unable to explain what they had seen over there, on the other side.

From Hate to Love

For the Photography USA guides who continued working on the exhibits program — some as employees of increasing seniority at the Moscow embassy, USIA, or the State Department — a funny switch occurred as the years progressed. In the 1970s, they had the frustrating experience of having to correct the negative myths about the United States that pervaded the attitudes of Soviet visitors. By the late 1980s, they had to do the opposite — convince many Soviet citizens that the streets in the United States were not paved with proverbial gold.

Did the exhibits contribute to this turnaround in attitudes and the ultimate demise of America’s greatest geopolitical rival? Some guides believe they did. “In the six years that I worked on the exhibits,” Ambassador Tom Robertson told me, “I saw a change in the Soviet propaganda when it talked about problems in the United States. When we got there, they were talking about how terrible American unemployment was. By the time we left, in ‘78 to‘79, you would notice that the attacks on the U.S. domestic political system had changed. It became more sophisticated. They would now mention posobiya po bezrabotitse (unemployment benefits).” In his view, after millions of people in the Soviet Union’s major cities saw the exhibits and heard the guides talk about unemployment benefits, the Soviets simply couldn’t continue saying that Americans were dying in the streets because they were unemployed. In 1977, the Russian girlfriend of one of the Photography USA guides thought that for him, going back to America must have felt like going back to jail, but in the 1980s the same guide reported an encounter with an exhibit visitor in Moscow who told him, “It will take us 500 years to catch up to you. 500 years!”

As I talked to the guides, another question kept popping up: why did the Soviets even allow the exhibits? They must have realized the psychological impact that they had on visitors, creating or reinforcing for many the longing for a new and freer life, demolishing the results of decades-long propaganda efforts. The talkative, direct, and fearless American kids standing in the middle of crowds of Soviet visitors, honestly answering questions in these unmediated encounters, should have epitomized everything the Soviet system feared.

In fact, they did; the exhibits were a non-negotiable part of the agreement for the Americans, the quid pro quo in return for the scientific exchanges that were so critical for Moscow. And so the Kremlin had to let what from their perspective must have been a corrosive influence into their country. Having agreed to the exhibits, the Soviets did as much as possible to make the organization difficult and to undermine attendance. They prohibited media coverage and harassed people standing in line. Those who spent too much time in the company of the guides were liable to attract negative attention from the authorities. But none of that deterred the crowds.

Wearing Each Other’s Shoes

I didn’t go to that photo exhibit in Novosibirsk. I was only seven at the time and that summer my parents were busy preparing me for my first year in school. Preparations often involved traveling to Moscow to stand in long lines to purchase school uniforms, school bags, “decent” (i.e., imported, usually from Soviet bloc countries) shoes and clothes, and other items that often could only be purchased in the capital. They also involved feats of do-it-yourself design and sewing to create additional accoutrements, such as dressy, white aprons that all Soviet girls wore to school on special occasions.

This aspect of my Soviet childhood may be one of the reasons that one particular story stands out among the many that the guides shared with me.

One day, Kathleen Rose and another female guide came into the possession of Soviet schoolgirl uniforms. Kathleen, who decades later posted the story on Facebook, wrote that they “hatched a plan to put on [the] uniforms and wander around Moscow. We had spent so many months being foreigners / outsiders that we wanted to know what it felt like to belong and hoped that in the uniforms we just might pass as natives, given that we were only a few years older than actual Soviet high-schoolers.”

“We wandered around the city, arm in arm, as we had seen schoolgirls do. When we came back to the Metropol Hotel, where we were staying, they wouldn't let us in. It appeared that we had gotten our wish to be taken as natives, but not in the way we had hoped.

“Unable to convince the authorities that we were hotel guests, we had to request that someone bring us our passports. Finally, after much bureaucratic kabuki, we were allowed in the hotel. As we walked down the hall to our rooms, we saw our dezhurnaya [the hotel floor attendant] sitting at the end of the hall. A friendly, grandmotherly figure, she had taken us under her wing during our stay in the hotel. At the time, I thought of her as ancient, though she wasn't even as old as I am now. This time, when she saw us in our outfits, she drew herself up to her full five feet and said, ’You have no SHAME.’”

It made Kathleen feel guilty: “It had never occurred to me that wearing the uniforms was going to offend someone. Perhaps it was the Young Pioneer scarves that put her over the top.” She concluded:

“Recently, a Russian friend saw the picture of us and opined that the reason we were not let in the hotel was that we looked more like hookers than schoolgirls. This had never occurred to me either, though looking at the picture now, I see her point. Definitely a failed cultural experiment.”

What surprised me, profoundly, about this story is that these American women had a desire to walk in our shoes at all — or our uniforms, as it were. Thinking back to that time, I could imagine myself longing to trade places with the guides, wanting to try on their clothes, their ways of being, their entire lives. We would have desperately wanted their approval. Among the representative questions that the guides reported to USIA were these: “Do American young people dress differently from us?” “How do our young people look to you? Do they look and dress like Americans?”

I could have never imagined that Americans might have wanted to do the same- that as much as we wanted to understand what life felt like as a young American, they wanted to understand what it felt like to be in our Soviet school uniforms, in our homes, in our lives.

Maybe that was the most powerful aspect of those cultural exchanges. It gave both sides a chance to try on each other’s lives, to travel through the looking glass and see what life was like on the other side. Just as the Soviet citizens remembered those exhibits for the rest of their lives (my father claims that the Education USA exhibit, which he saw in 1970, solidified his desire to emigrate), for the young guides, their lives after those journeys were never quite the same. Many went on to pursue careers in the Foreign Service, moving as high up as an ambassadorship.

Perhaps even more importantly, all have remained keenly interested in Russia. Their interest in the country is genuine and open-minded. They see the negatives, but they also know the positives, because back then, many years ago, they allowed the people they met there into their hearts. By breaking through the veneer of propaganda and political posturing, USIA helped connect everyday Americans and Russians in a way that the Cold War rarely allowed for. Although sprawling and massively expensive, the program brought together elements of each country’s society in perhaps one of the most successful hearts-and-minds campaign the United States has ever undertaken.

* * *

Learn more about the guides and read their recollections here.

See rare photos of the Soviet exhibit-goers here.

* * *

Izabella Tabarovsky is a Senior Program Associate at the Kennan Institute. She writes about the politics of historical memory in the post-Soviet space, the Holocaust in the Nazi-occupied Soviet Union, and Stalin’s repressions.

Cover photo courtesy of Robert Fenton Houser