War in the age of the smartphone

– Miriam Kelberg

Like regimes throughout the world, Syria’s Assad has routinely shut down his nation's internet access in order to secure military victories. What is it about the internet that so threatens the world's despots?

Over the duration of the Syrian Civil War, there have been countless instances of nationwide internet, mobile phone service, and electrical blackouts. A new study by Anita R. Gohdes, a researcher at University of Mannheim, argues that these instances are not accidental. Instead, they are strategically executed by the Syrian government as a part of their military strategy against rebels.

It’s not new for incumbent regimes to use internet blackouts to squash opponents — both real-life and imagined. In the 2009 uprisings in Iran, the government allegedly disrupted internet access soon after the elections, while text messages were blocked during the entire election period. The regimes in Libya and Egypt acted similarly during antigovernment demonstrations in 2011, cutting off Internet access in a failed attempt to hold onto power.

The Syrian government clearly understands the importance of a strong online presence. President Bashar Al-Assad’s dynamic Instagram account updates the world on his goings on, with the evidence of a civil conflict curiously absent from his narrative. Given the Assad regime’s robust Internet presence, what advantage do they (or other regimes) gain from limiting internet access? It all has to do with the myriad ways technology has changed how war is fought.

“The civil war in Syria presents the first case of large-scale civil conflict that has been painstakingly captured, documented, and communicated via the internet,” writes Anita R. Gohdes in the Journal of Peace Research. Whether through YouTube videos, tweets, or Facebook posts, the internet has been key to moving information out of Syria and into the broader world. For rebels inside the country, smartphones allow for speedy coordination of people, strategy, goods, and, ultimately, mobilization. Geographical location systems and apps like Google Maps and Google Earth enable rebel groups to target regime forces with “a level of precision that was not available a decade ago,” writes Gohdes.

Recent interviews with members of the Free Syrian Army (FSA) offer further insight into the practical uses of smartphones in wartime Syria:

“Every fighter seems to have at least one mobile phone, used to speak with families, Skype ... and even advise Syrian soldiers how to defect to the opposition. Some note the difference a generation can make to the fate of their challenge against the government — and providing video evidence of atrocities and war crimes that are corroding the legitimacy of the regime.”

Gohdes’ study finds that short, nationwide shutdowns have been used in order to disrupt digital networks and win short-term military victories against rebel groups. Using a Poisson exponentially weighted moving average model to analyze the correlation between internet shutdown and increases in the number of deaths among antigovernment forces, Gohdes found that “on average, the level of violence increases by 26.3 percent on the day prior to an internet outage. During the actual blackout, violence is predicted to increase by 8.6 percent, and when looking at the time window, the average increase is predicted to be almost 47 percent.”

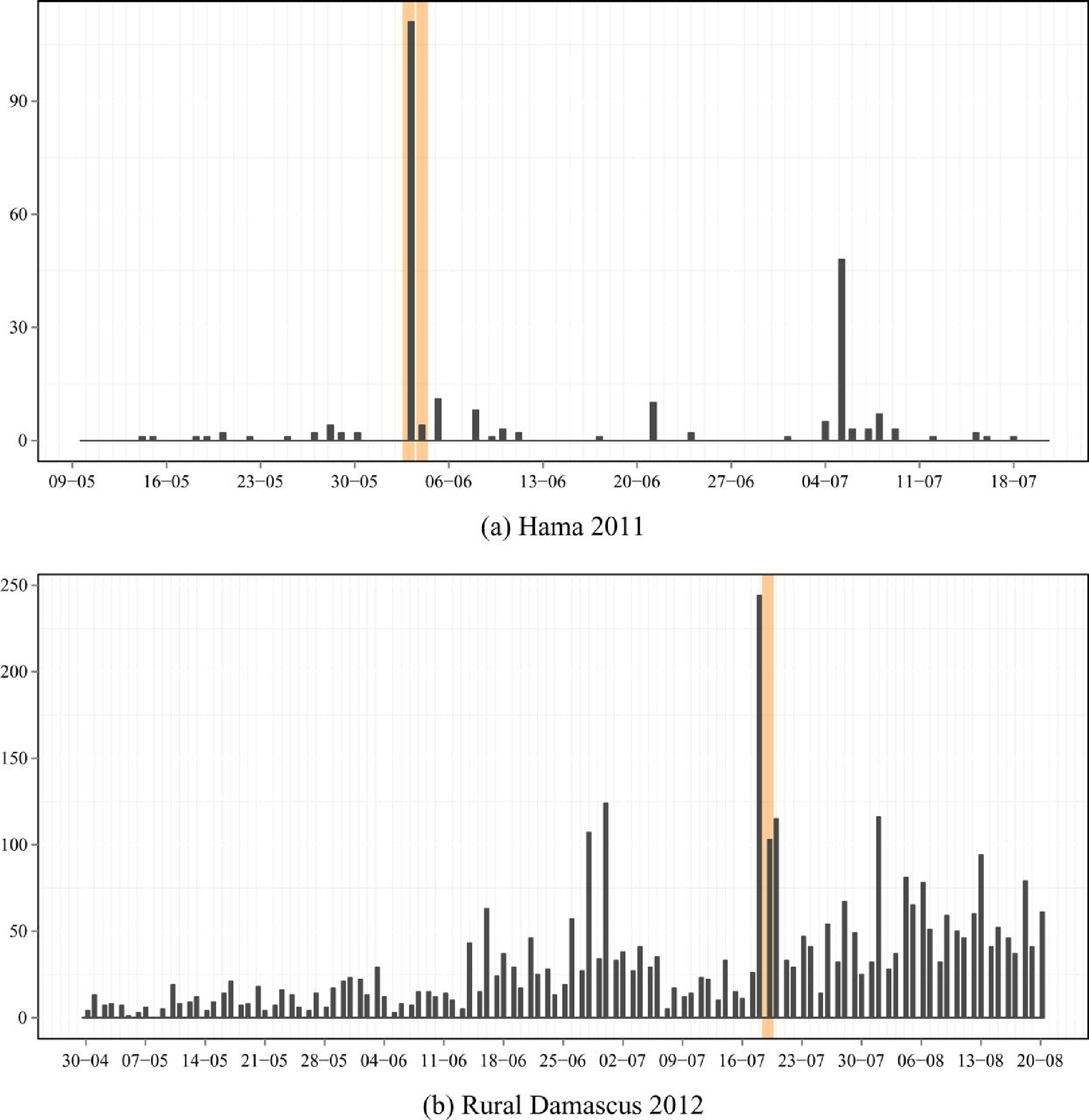

The graphs below show the number of deaths per day in Homs (a) and rural Damascus (b) in 2012, with the orange-shaded days representing periods when the internet was down nationwide. During the internet shutdowns, the death counts are remarkably higher, suggesting that the shutdowns have been effective for the regime, at least in the short term.

Some observers have speculated that shutting down the internet is a strategic choice by the Assad regime, giving them cover to commit mass atrocities while opponents are unable to tell the international community in realtime. Ultimately, Gohdes argues that this is not the case, pointing out that the victims during internet shutdowns are more likely to be civilians — a different population than those killed in non-shutdown times (who are more likely to be insurgents). Moreover, significantly increased fighting occurs in the day prior to blackouts, which perhaps would not be the case if the government was using the shutdown to hide an atrocity from the international community.

No one seems to know when the conflict will end in Syria or when people will be able to rebuild their communities. One thing that is known: the internet is rapidly changing the way insurgency warfare is fought.

* * *

The Source: Anita R. Gohdes, “Pulling the Plug: Network Disruptions and Violence in Civil Conflict,” Journal of Peace Research 52:3 352-367.

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock/1000 Words