Winter 2020

Why Protest?

– S. Erdem Aytaç and Susan Stokes

2019 was a year of global protest. Was it democracy in action, or democracy in crisis?

The second decade of this millennium will be remembered as a decade of protest.

In early 2011, the Arab Spring surprised the world – as well as the autocrats that these movements targeted. Toward mid-decade, massive demonstrations took place in Brazil, Turkey, Ukraine, and Hong Kong. On January 21, 2017, the largest number of demonstrators ever – five million of them – massed on the streets of American cities for the Women’s March.

The consequences of the Arab Spring protests rippled through the decade, bringing regime change, warfare, and refugee crises. In Tunisia, they paved the way for a sustained new democracy. Yet the magnitude of these protests pales in comparison to the end-of-decade tsunami of mass demonstrations. Several million citizens have mobilized around the globe in 2019, crowding into streets and squares from Ecuador to Tehran, Santiago to Beirut, Delhi to Paris, and beyond. In Hong Kong alone, as many as 1.7 million citizens have demonstrated on a single day – in a city whose total population is seven and one-half million.

What are the causes of these protests? Why do they appear to be on the rise and clustered in time, as in “waves,” and which dynamics play a role in people’s participation in them? Why do protests sometimes provoke harsh governmental responses, and, at other times, concessions? Are protests a symptom of democracy in action or democracy in crisis?

Sparks Into Conflagrations

Along with petitions and initiatives, citizens have used street demonstrations to bring grievances before the public and make claims against governments for centuries. And although public, open-air meetings have long been deployed by political parties and labor unions, open-air demonstrations now are increasingly used by less tightly organized sets of citizens and residents, including people who take part alongside of friends and family, as members of neighborhood groups, or even as a result of their own initiative.

These organizationally inchoate protests often begin with very specific complaints, but grow to have a broader meaning and to embrace broader demands. In the present wave of protests, the spark may be an assault on citizens’ pocketbooks – a spike in taxes (Lebanon), gas prices (Iran), or public transit fares (Chile), or more general economic grievances (France, Colombia, and elsewhere). Sometimes politics provides the spark – an election stolen (Russia, Bolivia), passage of an unpopular law (Hong Kong, India), or the revelation of corruption (Iraq). Sometimes government inaction creates the grievance, such as pervasive gun violence in the U.S. or global protests about climate change.

Protesters’ demands often broaden once the spark leaps into flame. The Hong Kong protests began in June 2019, after the government proposed an extradition bill that would have allowed the transfer of individuals to mainland China. Yet the proposed law also raised questions about a more significant erosion of the one country, two systems principle that links Hong Kong to mainland China, and protesters’ demands soon grew to include the resignation of Chief Executive of the Hong Kong government.

.jpg)

In Iran, protests against gas-price hikes took on broader anti-government connotations. And in Chile, resistance to public transit fare increases morphed into complaints about government indifference to income inequality and about constitutional provisions put in place by the military regime, thirty years earlier.

These kinds of grievances are powerful, but they are not new. Why, in our age, are so many people on the streets in so many regions around the world?

Several explanations have been offered for the recent wave. One is that income and wealth inequalities have persisted and worsened in many regions. Recent reports of the U.N. Development Program indicate that the majority of households in developing countries live in societies where income inequality is worse than it was in the 1990s, and that people who are already at the very top of income distribution benefit most from economic growth. The U.N. also warns that if current trends continue, the global top 0.1 percent will own as much wealth as the middle 40 percent of the world’s population.

Protesters’ demands often broaden once the spark leaps into flame.

“Democratic deficit” is another factor. In countries that are formally democratic, and especially in new democracies, the public has grown disappointed by corruption, incompetence, and lackluster economic results. A recent cross-national poll reports that 85 percent of citizens in Mexico are not satisfied with the way democracy works in their country; 83 percent of Brazilians, 70 percent of Tunisians, 64 percent of South Africans, and 63 percent of Argentines are likewise dissatisfied, Such discontent with democracy has increased over time in many countries. And pessimism about economic opportunities and frustration with elected officials is related strongly to dissatisfaction about the way democracy works.

Many analysts also point to a third common factor: the digital revolution. Social media and mobile phones with cameras have become especially important. Social media platforms allow organizers to spread the word about demonstrations efficiently and effectively, allowing would-be participants to learn about protest events with negligible information-gathering costs. One study even found that cell-phone penetration was a predictor of the size of protests during the Arab Spring.

In Hong Kong, protesters have used an app showing the location of the police, water cannons and tear gas use, allowing them to avoid potentially dangerous areas. Apple later removed this app from its store, a day after facing criticism in the Chinese state media, but it remains available on other platforms.

A fourth likely factor in the rising frequency of protests is cross-fertilization or demonstration effects. Governments themselves claim that foreigners instigate rebelliousness, as when leaders in Bolivia and Ecuador complain of Venezuelan instigators (not very credibly, in these instances). Beijing’s claim of US instigation of Hong Kong protests (and interference in November local elections) is likewise fanciful.

One study found that cell-phone penetration was a predictor of the size of protests in Arab Spring cases.

More plausible is not direct organizational support from foreign sources, but rather the encouragement that demonstrations occurring in one country – often disseminated globally on social media as well as in news outlets – can offer to potential demonstrators in other countries.

Why Bother?

While these factors are compelling, they fail to account fully for an individual’s participation in protests. After all, the participation of any given individual is unlikely to make difference to the protests’ success; moreover, in most circumstances everyone would benefit (or suffer) by the outcome of the movement regardless of taking part or not. There are also what social scientists would call costs of participation: time, money, and effort one puts into the movement. Thus, even in the presence of the structural factors mentioned above, the question remains: Why bother?

In our research, we argue that focusing only on the costs of participation is one-sided. In certain circumstances, people experience an internal friction when they fail to take part in collective actions, like protesting, aimed at producing goals that they support. That is, just as participation in protests is costly, abstention can be costly as well. The costs of abstaining from a protest are intrinsic and psychological, but no less real for that. It is this play between costs of participation and costs of abstention that determines people’s likelihood of coming out into the streets, and hence the size of protests.

We have shown that the costs of abstention mount when one feels that much is at stake in a given protest. The manner in which movement activists frame these grievances matters, too; appeals to emotions and conscience can be powerful mobilizers. When people experience anger or moral outrage, which psychologists call approach emotions, they are energized and more willing to engage with others and tolerate risk.

Social movements that successfully construct a causal framework that casts grievances as a form of injustice, especially an injustice purposely carried out by an identifiable agent, are more likely to see angry people pouring into streets.

This framework also explains an unexpected effect of police violence. Sometimes, such violence stokes protests, rather than suppressing or deterring them. Recent mobilizations in Chile and Hong Kong illustrate this dynamic of repression, in which street conflict sometimes encourages – rather than discourages – particular protests.

.jpg)

We argue that repression can drive up people’s costs of abstention by eliciting by-standers’ outrage and anger and their sense of being remiss if they stay home. The proliferation of hand-held cameras also allowed video clips of police abuses of demonstrators to be captured easily and communicated widely to the public. This dynamic was at work in Turkey’s Gezi Park protests in 2013. One protester explained to us in an interview:

“When [most people] saw the pictures or the video footage [of repression] they were scared. But they thought that they had to be there, because people like them were being attacked, persecuted, suppressed, and almost everybody said, ‘I had to be here.”’

The costs of abstention mount when one feels that much is at stake in a given protest.

Surely, tear gas, pepper spray, and police bludgeons by definition increase the costs of participation, and, thus, create a demobilizing effect. What we have found is that low-to-medium levels of repression can increase protest sympathizers’ costs of abstention more quickly than it raises their costs of participation, and draw them into the streets. At higher levels of repression, the instinct to protect oneself from harm is likely to dominate any urge to participate in most people.

In sum, police repression can both mobilize and demobilize protesters and bystanders; its impact will be the net of the two effects. Social movements that maintain an image of nonviolence, and at the same time publicize acts of violence by the other side, are likely to mobilize more people among their ranks.

Movements that can field large crowds initially and keep this momentum alive are likely to draw even more people among their ranks. Success breeds success. Large crowds can be a source of enthusiasm or give the impression that the movement is likely to succeed; not taking part in such circumstances leads to greater psychic dissonance than in the case of a small protest.

When Do Governments Crack Down?

When protests are sufficiently large or disruptive, governments respond. Sometimes they respond harshly, and sometimes they offer concessions. What explains this variation?

In our research, we identify a particular government’s security in office as a key factor. Secure governments are the ones that maintain stable electoral support, and they calculate that their electoral security is unlikely to be disturbed by repressing protesters. Therefore, they feel free to inflict harm at higher levels and suppress protests.

Vladimir Putin’s government in Russia exemplifies an electorally secure government facing protests. When opposition-leaning Muscovites filled the streets in the summer of 2019 to protest, a violent crackdown by police ensued, leading to detention and arrest of hundreds of protesters.

.jpg)

In contrast, less secure governments, those with volatile electoral support, are warier of (future) electoral sanctions when they repress protests. They behave with more restraint. These governments are more prone to back down and make concessions to protesters, even if this entails costly policy reversals.

In Chile, during most of 2019, more people disapproved than approved of President Sebastián Piñera’s performance. At the time when the protests began, the gap between approvers and disapprovers was 20 percentage points. After the initially harsh treatment of protesters, Piñera’s disapproval rate surged to 78 percent, and his approval sank to 14 percent. This helps explain why Piñera backed down on transit increases, reshuffled his cabinet, and made proposals for constitutional reforms.

Raising the stakes for governments, the precise effects of repression – the degree to which it will encourage or discourage further mobilization – can be hard to calculate, ex ante. Even in authoritarian Iran, where an apparently entrenched government met November 2019 protests over gas-price increases with brutal force, there were signs of the government trying to soothe a seething public, after civilian deaths numbering in the hundreds.

A Corrective to Malaise?

We have observed that the past decade of protest has also been an era of skepticism about democracy, raising questions about whether elections can serve as a mechanism of accountability, and result in the elevation of responsive governments to power. Might protests serve to counteract this democratic malaise?

There are several reasons why this is unlikely to be the case. Protests are typically anti-deliberative: they are more about showing off power-in-numbers than deliberation and persuasion. Social movements are well suited to put brakes on bad policies but unlikely to usher new alternatives or policy coalitions.

Also: Even the biggest protests represent only a fraction of citizens in a country. Therefore, they cannot claim to represent the society, and potentially undermine both representation and majority rule. Disturbing the democratic equilibrium can easily provoke authoritarian backlashes approved by the broader public to restore order and cement majority rule.

The AKP government in Turkey, for instance, framed the 2013 Gezi Park protests as a major threat to representative democracy. The party successfully counter-mobilized its conservative base through “Respect for the National Will” meetings throughout the country, which helped to generate consent for its increasingly authoritarian practices among its supporters.

At the same time, protests can play a positive and crucial role for democracy. Most institutionalized mechanisms of democracy violate political equality one way or another. Simply put, those with more resources are more likely to shape election outcomes and public policy.

Social movements can serve as a powerful tool of disadvantaged groups and put pressure on the privileged. While elections are blunt instruments of accountability because they reduce many issues into a single choice, protests can channel specific demands, potentially enhancing government responsiveness. Similarly, elections happen only intermittently; protesters can react in real time to the actions of governments; this should lead to a more responsive government as well. Protesters in Brazil in 2013 and in Chile in 2019 were able to force governments to reverse unpopular increases in prices of public services without having to wait until the next election.

Raising the stakes for governments, the precise effects of repression – the degree to which it will encourage or discourage further mobilization – can be hard to calculate, ex ante.

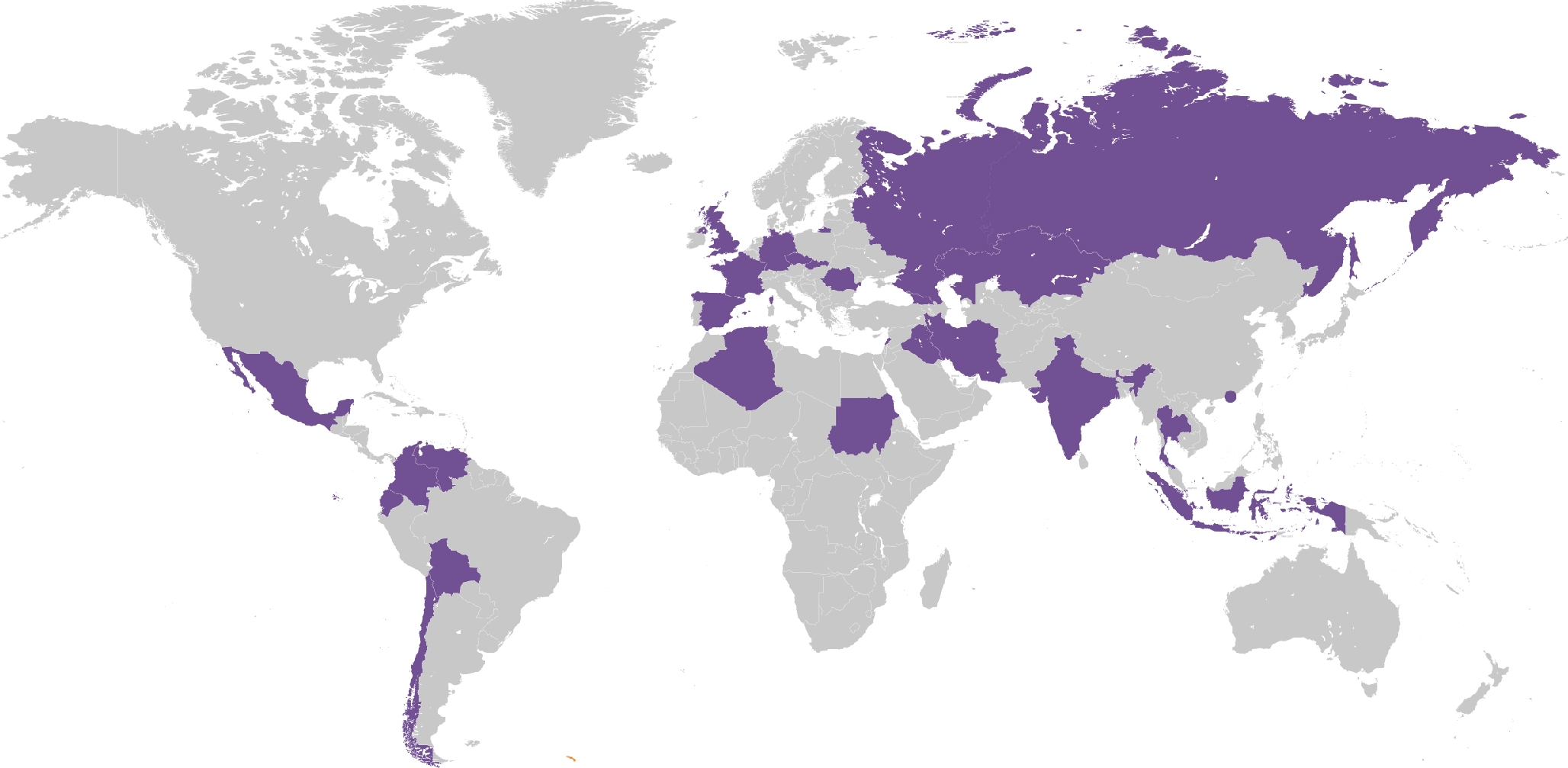

Finally, in a period where the greatest threats to democracy often come from elected leaders, social movements provide a crucial platform for resisting democratic backsliding. The Democratic Erosion database lists 119 non-violent protests in resistance to backsliding in countries around the globe, with mobilization especially frequent in South Korea and India but present in an additional 50 countries.

Would-be autocrats do not back down easily, and can be expected to raise the costs of participation of those who resist democratic backsliding. But the experience of street demonstrations everywhere shows that they do not inevitably succeed. Their actions can increase the moral and psychological costs to would-be demonstrators of staying home. When these costs of abstention outstrip the costs of participation, the streets will remain foci of democratic contestation.

S. Erdem Aytaç is an assistant professor in the Department of International Relations at Koç University in Istanbul, Turkey.

Susan Stokes is the Tiffany and Margaret Blake Distinguished Service Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Chicago and Director of the Chicago Center on Democracy.

Aytaç and Stokes are the authors of Why Bother? Rethinking Participation in Elections and Protests, published by Cambridge University Press (2019).

Cover Photograph: Communist party supporters wave red flags during a protest in the center of Moscow, Russia, on August 17, 2019. (AP Photo/File)