WQ Dispatch - June 2021

– Richard Byrne

A monthly look at what we're reading and watching.

We are working busily on the Summer 2021 Wilson Quarterly. The theme for the issue is "Conflict/Resolution," and we will examine treaties and agreements in an age of hyper-nationalism, discord and strife with essays and interviews on global health, intellectual property, energy and national security.

Look for the Summer 2021 WQ in your email in late July.

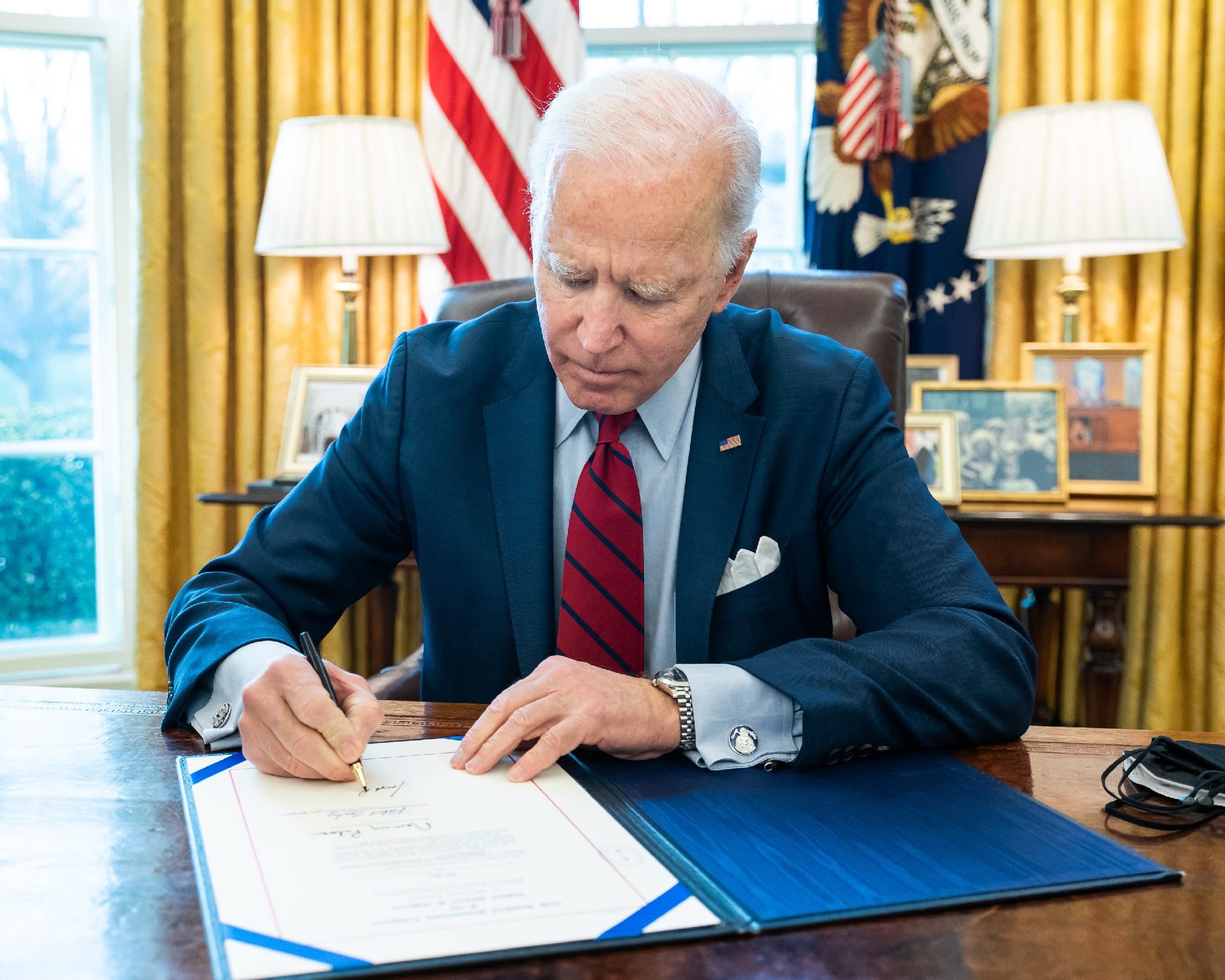

Our lead essay in the Winter 2021 issue – “The Hundred Day Mistake” – was among the most widely-read Wilson Quarterly pieces in recent memory. Alasdair Roberts – a professor of public policy at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and director of its School of Public Policy – made the case that the “First 100 Days” used to measure success since President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s push for a New Deal in 1933 would be unhelpful to the Biden White House.

Roberts' essay helped shape the conversation around expectations for President Biden in the administration’s opening days. (His argument against the "First 100 Days" framing even ended up on the front page of the Sunday edition of The New York Times in January.)

After President Biden’s first 100 days arrived on April 29, 2020, we reached out to Roberts to see what he made of Biden’s first months in office – and what may lay ahead for the president and his agenda:

Q: Your essay was very close to the mark on how President Biden approached his first 100 days - despite the Democrats winning slender control in both Houses of Congress. What did you make of Biden’s successes and failures in the opening months of his presidency?

A: The Biden White House did a good job of tailoring expectations about what could be done in the first hundred days. It moved attention away from the usual measure of success – a battery of legislative victories – and toward objectives that were important and achievable, like getting Americans vaccinated and providing economic relief. This was the right thing to do in terms of both politics and statecraft. The White House also made significant progress in getting key appointments settled, reversing Trump-era executive actions, and staking out its position on key issues. It lowered the temperature and conveyed the sense that it had matters in hand. Given the present-day realities of Washington politics, that is an impressive record.

Q: Your article challenged the necessity of a first 100 days blitz for new presidents. Does Biden's approach strengthen the argument for looking beyond this expectation?

A: Absolutely. It's unreasonable to expect any new president to achieve a swath of legislative accomplishments in the first 100 days, given the complexities of government and politics today. Moreover, there are real dangers in trying for a legislative blitz – the result might be bad law and even more political rancor. Treating the hundredth day simply as a "check-in" on presidential progress is less problematic, of course. Even then, however, it would make more sense to give a new president a longer stretch – maybe six months – before passing judgment on how a new administration is doing.

Q: Structural challenges and polarization will vex Biden going forward. In many ways, they have even intensified. Is Biden's approach to his first months in power a necessary path to achieve his aims leading up to 2022 midterms?

A: The room for maneuver in terms of achieving new legislation is very narrow, and the Biden White House will need to think very carefully about where to allocate its energy and political capital. The temptation, understandably, is to focus on major changes in substantive areas of policy. But I wonder whether the top-most emphasis ought to be on fixing the fundamental rules of the game – that is, legislation about elections and voting rights. This would have critical implications for policymaking in Washington for years to come.

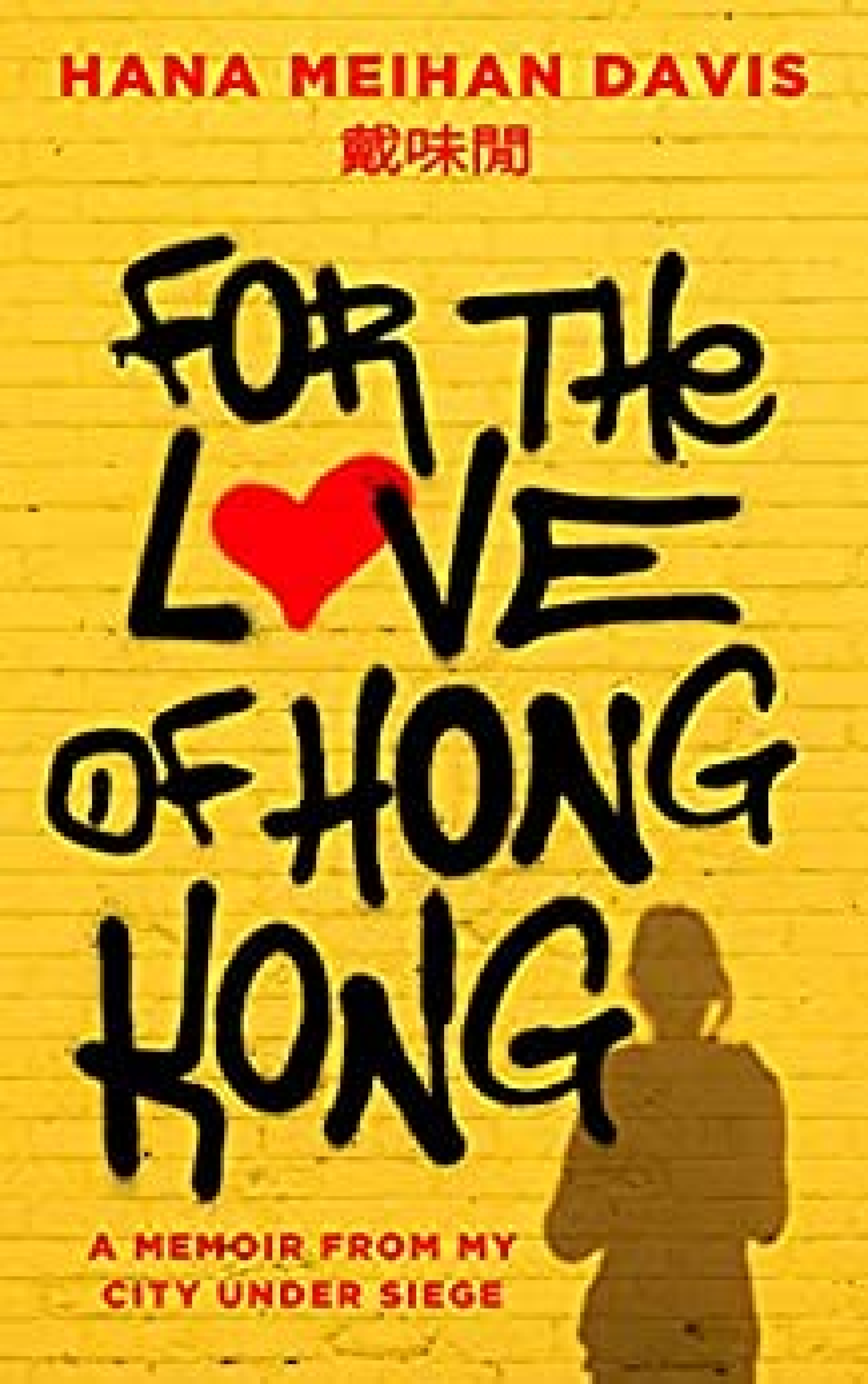

At the center of the WQ’s Winter 2020 issue (The Power of Protest) was “Protest Tech: Hong Kong” – an interactive examination of how Hong Kong’s massive 2019 protests were not only a manifestation of the city’s desire to retain its status as a bastion of liberty within the People’s Republic of China, but also a teeming laboratory for the future of organized protest in a surveillance state.

Over the past eighteen months, however, the democracy movement in Hong Kong has encountered setback after setback. China’s rulers leveraged the global pandemic to accelerate their timetable to seize control of Hong Kong, and strip away the protections built into the 1997 handover of the province to that nation by the United Kingdom. Sweeping and draconian laws have been introduced to neuter electoral politics, stifle protests and clamp down on free speech. In late June, one of the few independent media outfits still operating in Hong Kong – Apple Daily – was shuttered.

Global Fellow Michael C. Davis co-authored our interactive piece, and he is also a key figure in For The Love of Hong Kong: A Memoir From My City Under Siege (Global Dispatches) – a riveting new memoir about Hong Kong written by his daughter, Hana Meihan Davis.

Hana Meihan Davis’ sharp, evocative and economical prose makes For The Love of Hong Kong a perfect introduction to the current crisis – as well as a succinct primer on the history of the city and its democracy movements.

“Hong Kong is, after all, a city co-authored by Chinese imperialism, British colonialism, and the tightening stranglehold of Communist Chinese domination,” she observes. “To be a Hongkonger is to be a product of colliding empires, a rootless child defined by powers far away. The city is in many ways itself the exile, not fully belonging to the East or to the West. To be a Hongkonger is to be a dreamer, an inventor, a storyteller. Hong Kong needs its Platonic orators clinging tirelessly to its myth in order to survive.”

Proximity lends the author of For The Love of Hong Kong both perspective and authority in depicting the terrain of democratic struggle there. Not only are Hana Meihan Davis’ parents central figures in the movement, but her godfather, Martin Lee, remains a key mover in Hong Kong's democracy battles. Yet her account is very much the viewpoint rooted in her own generation's perspective.

“With no memories of a British Hong Kong,” she observes, “and no attachment to China, mine is the generation that most adamantly regards itself as “Hongkongers” — a term added to the Oxford English Dictionary after the pro-democracy Umbrella Movement brought the city to a 79-day standstill in 2014.”

Yet Hana Meihan Davis’ passion for Hong Kong isn’t purely political. Also woven into the book are richly-drawn reminiscences of her city, glimpsed from an exile imposed upon her by both pandemic and her status as a dissident in the city's new political landscape.

“While I assuage my appetite with regular trips to Chinatown,” she writes, “what I really crave is the ramshackle symphony of Hong Kong, to step from the too-cold air conditioning of the airport into the gasoline-tinged perfume of my city. I miss Hong Kong’s early-morning clamor, how it smells of chestnuts and exhaust fumes on hazy winter days, the red glow of wet market fruit stalls under the fading evening light, the loneliness that settles on midnight trams.”

For The Love of Hong Kong: A Memoir From My City Under Siege is published as part of a new imprint for short nonfiction works on world affairs created by Mark Leon Goldberg, host of the Global Dispatches podcast and creator of the UN Dispatch blog.

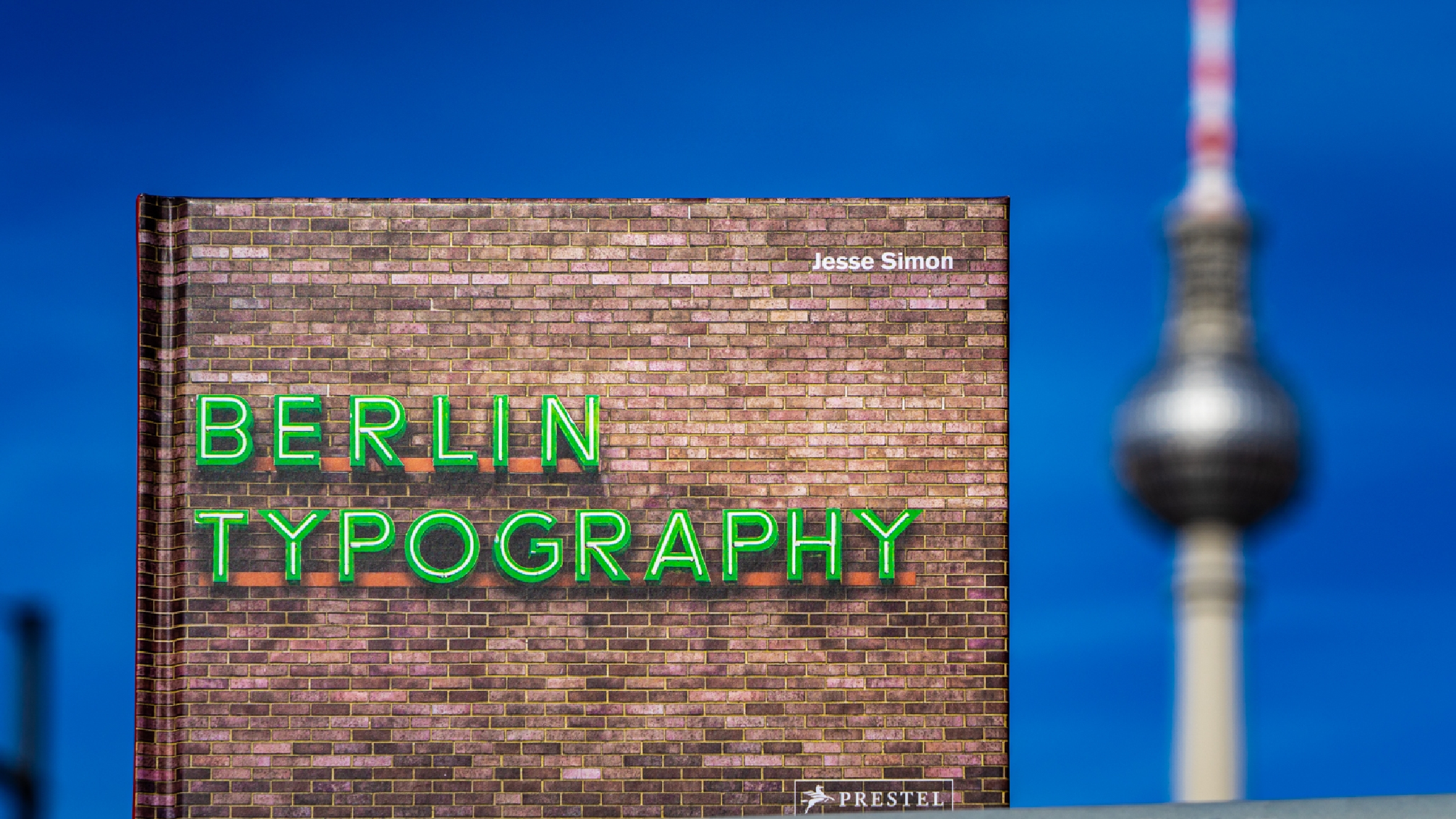

“Words define a city.”

That is the powerful argument advanced by Jesse Simon in Berlin Typography (Prestel) – a splendid new book that examines the power of public language manifested in the commerce, transit system and public spaces of Germany’s capital.

Simon has been working on the project since 2016, and publishing images and mini-essays on a website and on an active Twitter account. The author adds that the ephemeral nature of the Berlin words which he tracks so assiduously plays a key role in his quest:

When the Berlin Typography Project started in 2016, it was conceived initially as an informal investigation into the role of typography within the urban landscape, but it soon turned into a race against time. Signs are disappearing at an alarming rate, and it appears unlikely that much of the typography which defined Berlin in the twentieth century will survive the coming decades: metal corrodes, neon tubes break, paint fades, and even stone is smoothed by weather and time.

Berlin Typography places Simon’s photographs of the city’s distinctive words and typefaces at the center of the book. But there are abundant pleasures to be found in the author’s descriptions of various signs and other public language, some of which boast the tart laconic bite associated with the work of German-British art historian Nikolaus Pevsner. (A description of a sign for “Disco and Live-Musik” in the Wedding neighborhood notes drily that “ There has been no disco here for some time.”)

As I paged through Berlin Typography, I recalled my own first visit to Berlin in early 1991, a little more than a year after the Berlin Wall fell. One could still see and feel the divisions of the suddenly-open city.

On that trip, I stayed in Charlottenburg, which was still awash in neon. Simon observes that West Berlin “was a city of neon” in the 1960s, and quips that “ [e]ven funeral parlors were not afraid to break the sombre tone of their trade with a splash of neon.” Yet curiosity took me often over to East Berlin, where one could glimpse an entirely “other” city, with buildings still pockmarked with bullets from the battle for the city in 1945 and an entirely different aesthetic sensibility. Prenzlauer Berg, for instance, was bubbling over with new art galleries, seedy clubs, and squats.

Berlin Typography is essential reading for anyone who loves Berlin. But it should also appeal to anyone who values the character and distinctiveness that is lost as cities renew and reinvent themselves.

Cover photograph: Konstanzer Apotheke, Wilmersdorf, Berlin. (Image by Jesse Simon.)