A New Migration Agenda between the United States and Mexico

– Andrew Selee

Behind the rhetoric, what is the reality of U.S.-Mexican migration today?

Almost 16 years ago, two recently inaugurated presidents, George W. Bush and Vicente Fox, met at Fox’s ranch in Guanajuato to discuss matters of state and ended up tracing the broad outlines of a potential agreement on migration. Back then, they were both concerned with the large numbers of Mexicans coming across the border without documents, and wanted to make efforts to reduce and regularize this flow.

Today, the reality could not be more different. The number of Mexicans crossing the border illegally has dropped to a 40-year low, and there are almost certainly more Mexican immigrants leaving the United States than arriving. A majority of the immigrants crossing the U.S.-Mexico border illegally are now Central Americans, and the U.S. and Mexican governments have been working closely to find ways to limit this flow and keep people from making the dangerous journey north. And, perhaps most surprisingly, the number of Americans in Mexico has been growing rapidly, reaching somewhere around a million people, almost as large a group of U.S. citizens as live in all of the countries of the European Union combined.

The migration agenda between the two countries needs to be radically different today from what it was 16 years ago. Both countries have an interest in limiting unauthorized flows of migrants, ensuring an orderly, legal flow of people between the two countries, and ensuring expatriate services and consular protections to their citizens living in the other country. But each government will need the cooperation of the other to achieve these goals.

While public discussions of migration in both countries will continue to focus on the emotional issue of unauthorized migration between the United States and Mexico, the most important flows northward will continue to be from Central America, which requires bilateral cooperation rather than unilateral efforts. And public polls show that unauthorized immigration overall is actually an issue that matters less and less to the American public, who actually show more interest in fixing the legal immigration system.

Today, Mexico is a sending country, a country of transit, and a receiving country for migrants, while the United States is both a sending and a receiving country. We need to adjust our frameworks to recognize this new reality, and begin to develop policies that address greater complexity in the migration relationship between the two countries. Fortunately, over the long term, this greater complexity will actually present a source of balance for the bilateral agenda and an opportunity for creative engagement, although it may take a while for both public perception and public policy to catch up to our changed circumstances.

Mexican Migration to the United States

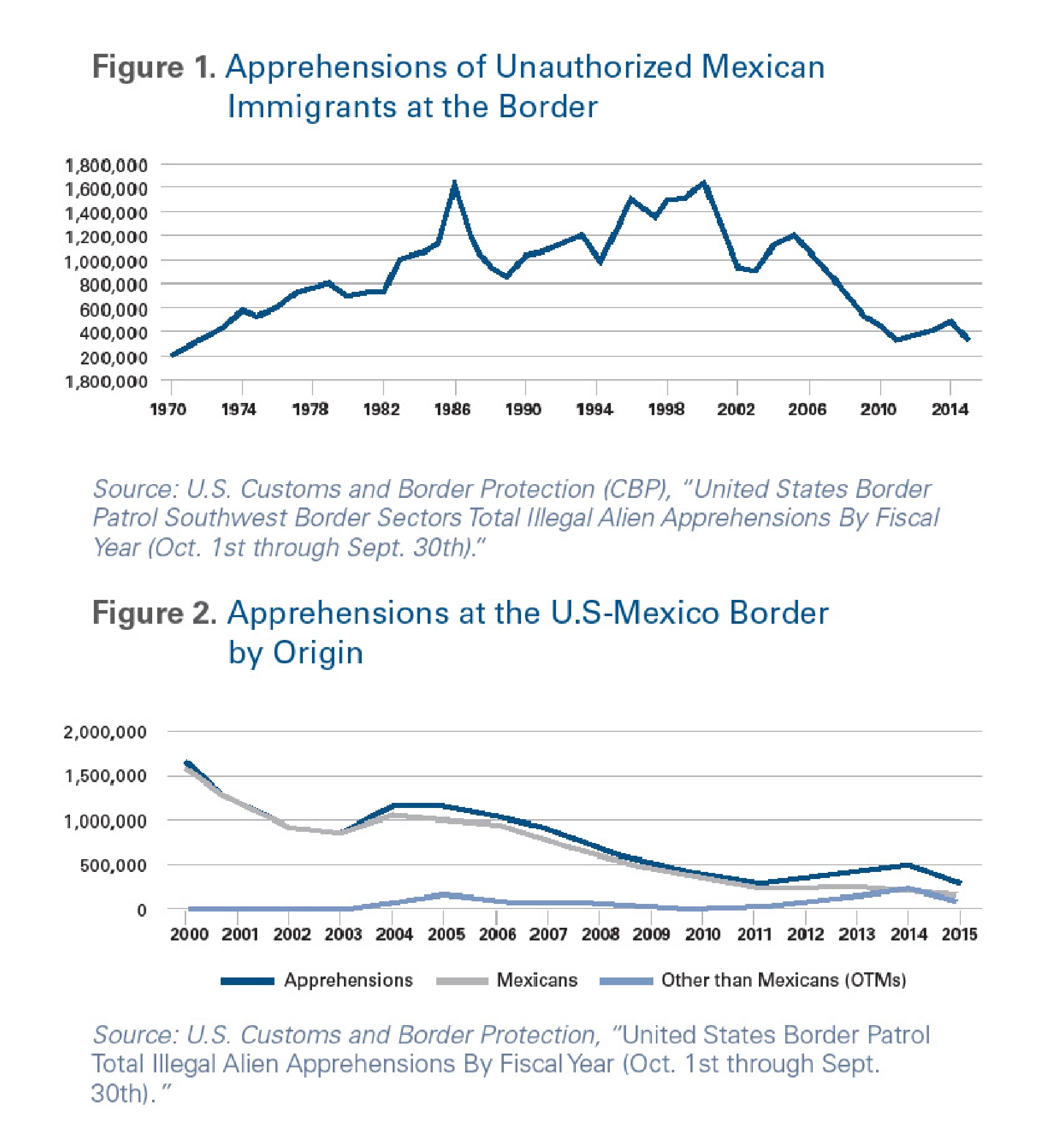

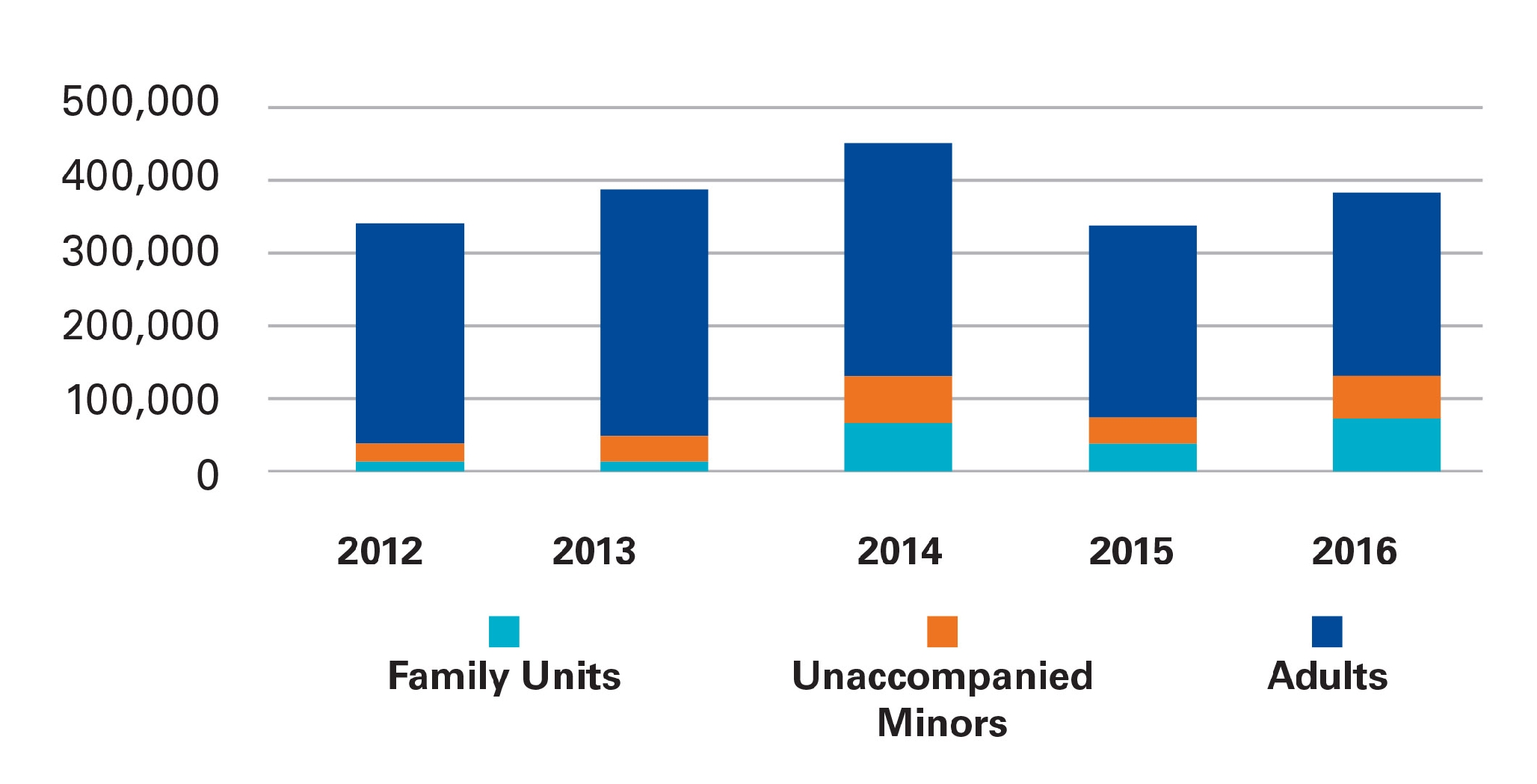

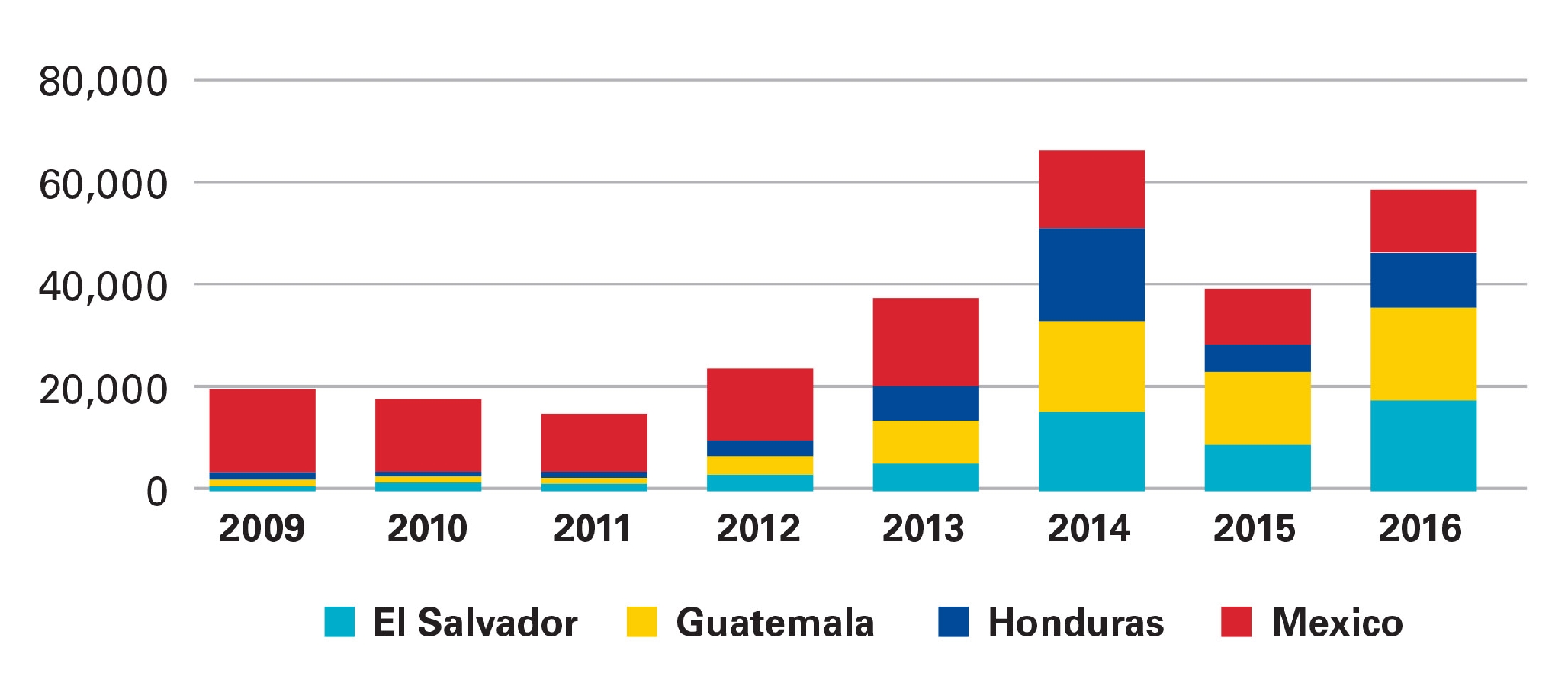

Unauthorized migration from Mexico to the United States once dominated the bilateral relationship, but it has reached a low point after four decades, according to apprehension statistics kept by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (figure 1). As the numbers of Mexicans crossing the border illegally has dropped, the number of Central American unauthorized immigrants, fleeing both poverty and violence in the Northern Triangle countries of Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras, has increased and now has surpassed Mexican unauthorized migration in both 2014 and 2016 (figure 2).

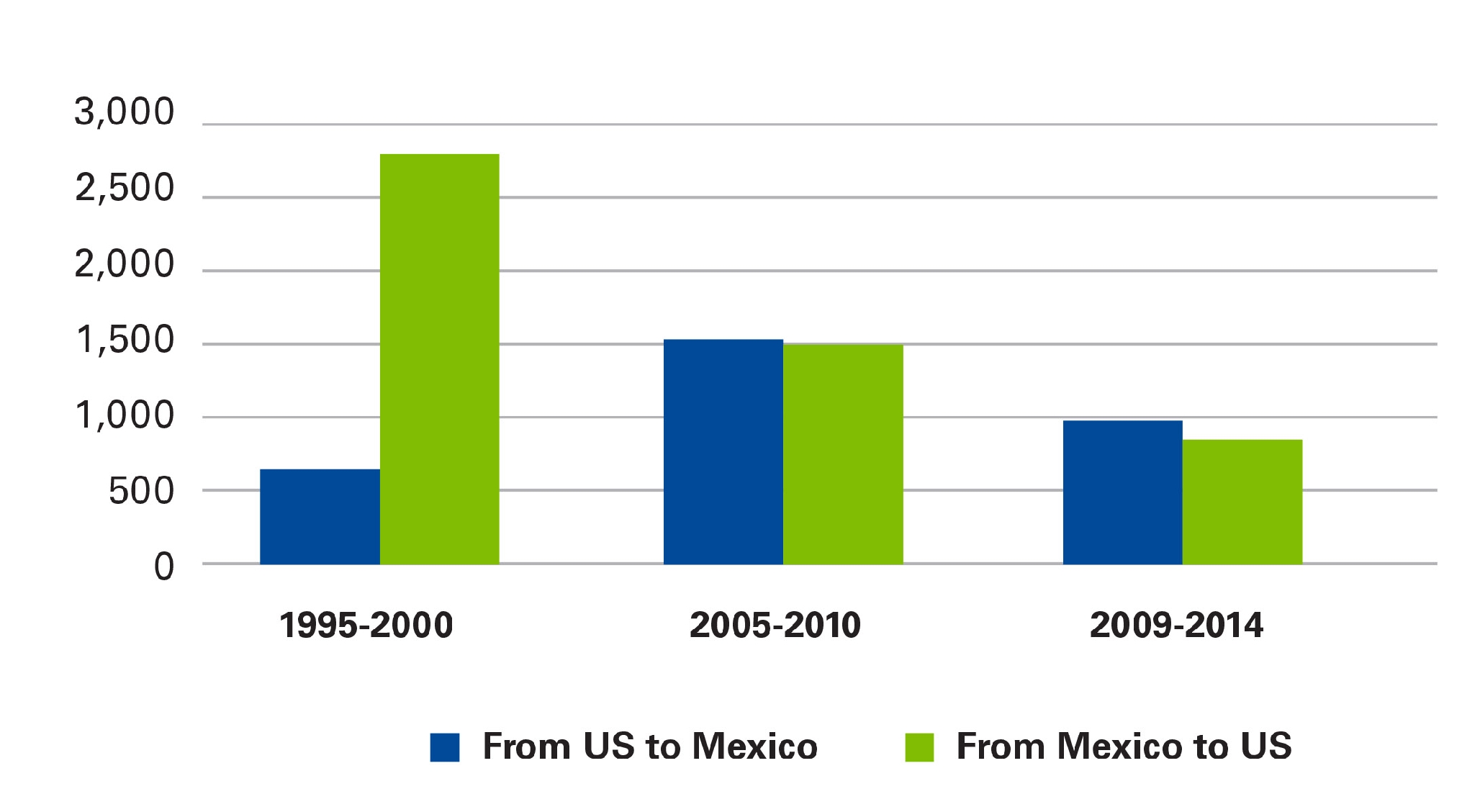

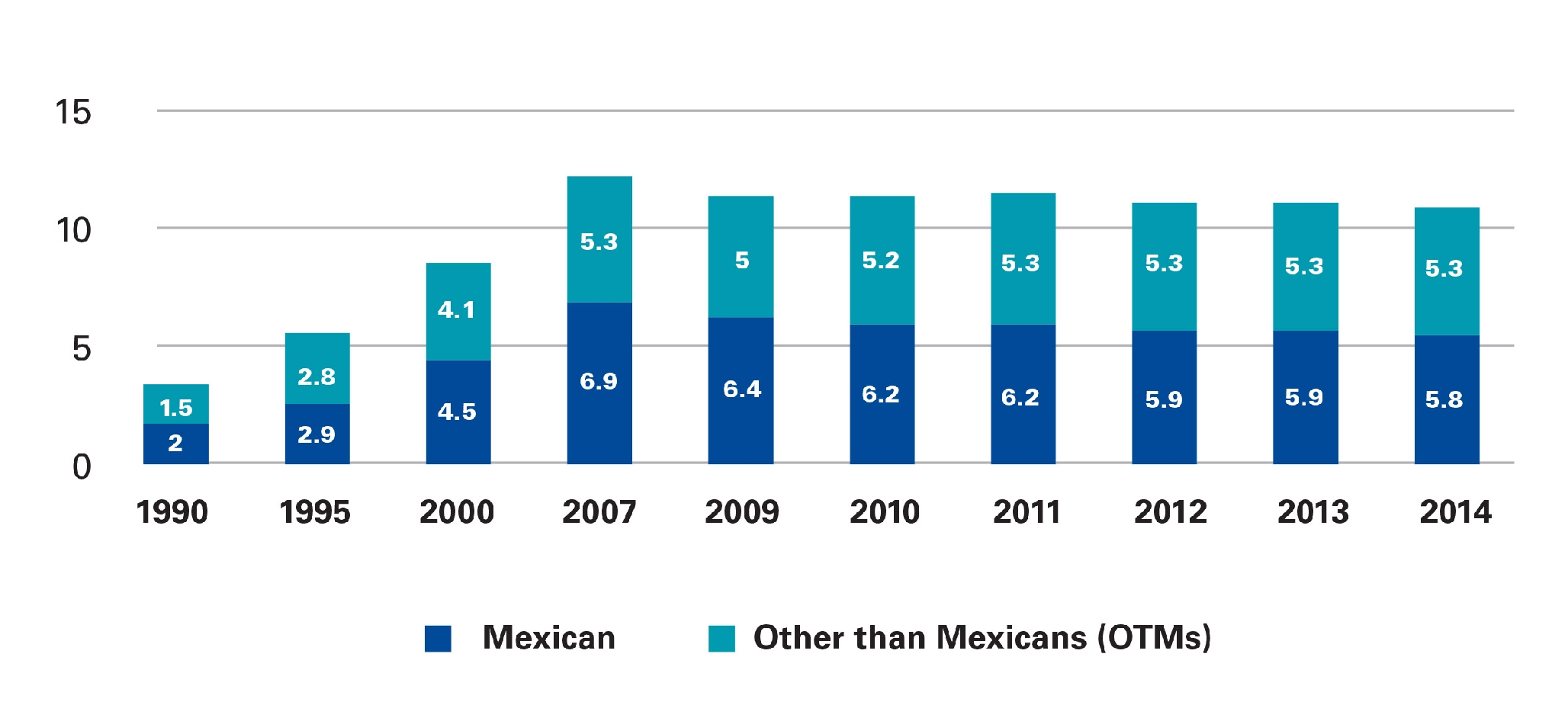

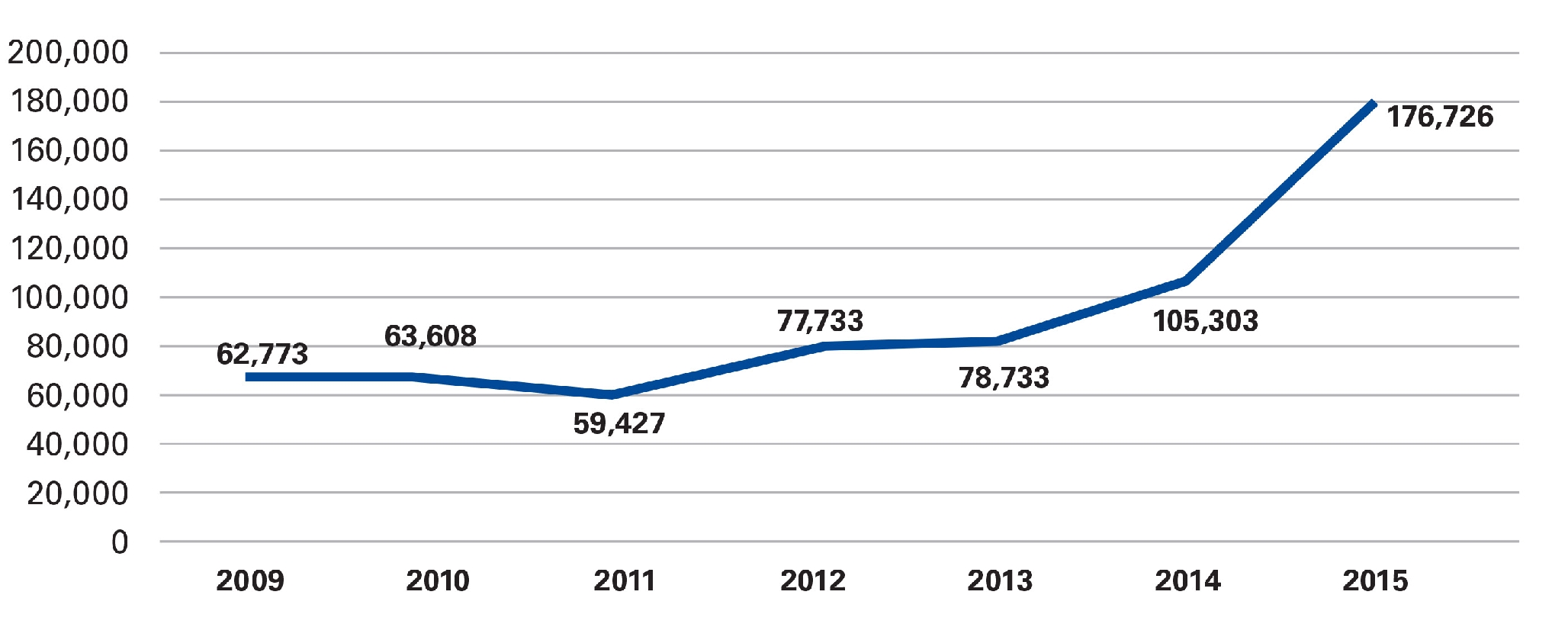

There has also been a marked uptick in the number of Mexicans returning to Mexico, including large numbers of unauthorized immigrants, according to research by the Pew Research Center. Today, more Mexican immigrants are leaving the United States than are entering (figure 3), and they are a declining percentage of the unauthorized population as a whole (figure 4).

Figure 3. Mexicans Migrating North and South

Figure 4. Unauthorized Population in the U.S. by Origin (in Millions)

By all appearances, this shift is a result of three factors. First, better opportunities in Mexico and a slower-than-usual U.S. economy have made it more attractive for Mexicans to stay in their own country than migrate northward. Mexico’s economy has been growing slowly over the past two decades, and incomes are roughly a third greater than what they were 20 years before while education completion has expanded by more than 50 percent. Second, Mexico is also facing the end of the demographic youth boom, with fewer young people ages 15 to 29 willing to migrate north for the first time.

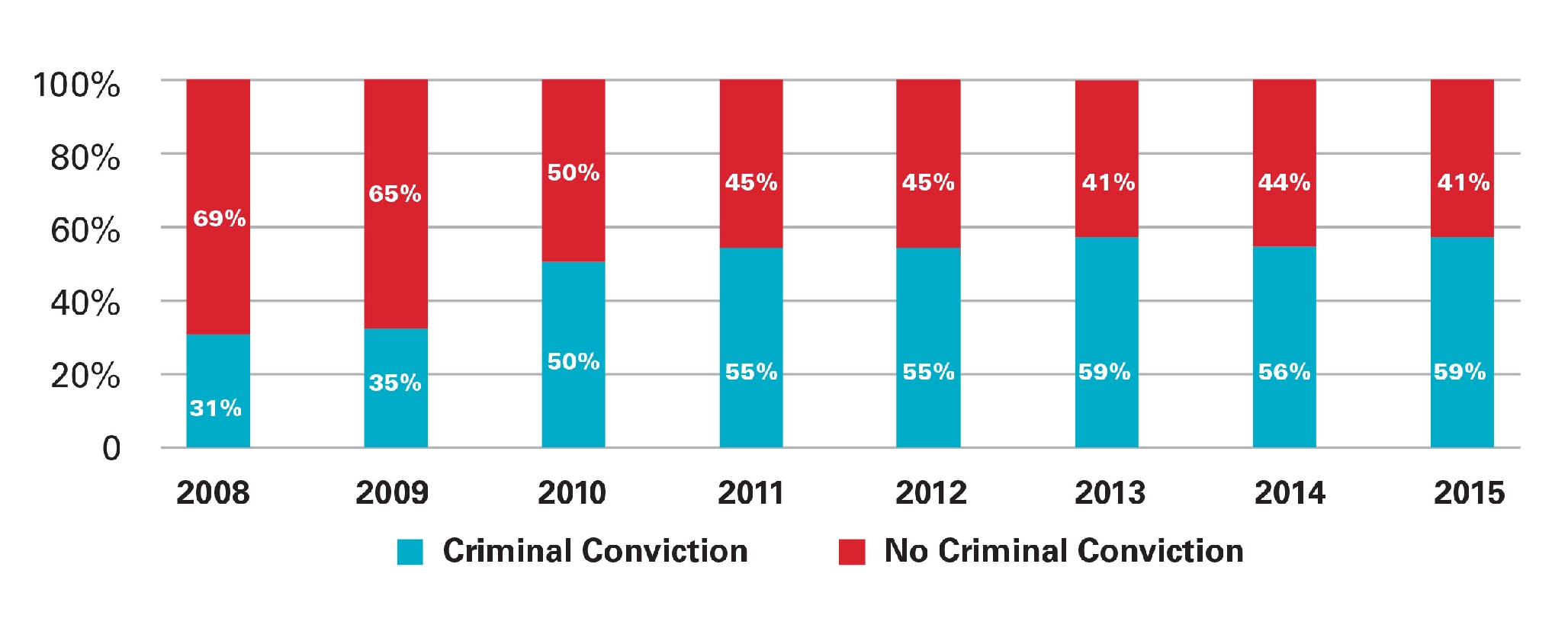

Finally, tighter border security and internal immigration enforcement have made it harder and more expensive to cross the border. This has included a 15-fold increase in immigration enforcement agencies’ budgets since 1986, which now spend more than all other federal law enforcement agencies put together; a gradual expansion of E-Verify to determine work eligibility at nearly a quarter of all places of employment; and significant new technology that makes detection of unauthorized border crossers easier. The expansion of cooperation between local law enforcement and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has also made it easier to identify and deport unauthorized immigrants with criminal convictions, who today comprise roughly 59 percent of all deportations (figure 5).

Figure 5. Percentage of Deported Immigrants with a Criminal Conviction

Immigration enforcement accounts for a significant part of the decline in unauthorized immigration, especially at the U.S.-Mexico border, but economic factors — the laws of supply and demand — have played an even greater role in this decline. Part of the challenge going forward will be to ensure that there is a balance between enforcement, which plays a legitimate deterrent effect on unauthorized immigration, and encouragement for continued progress on economic gains in Mexico, which is the single most important factor for limiting out-migration from Mexico. The United States has a powerful self-interest in ensuring that the Mexican economy continues to grow and develop, since that is the primary anchor preventing a return to large-scale migration north. There are also good reasons to continue to focus enforcement efforts on unauthorized immigrants with criminal records, a number that the Migration Policy Institute estimates at a little more than 800,000 individuals, of which roughly 300,000 have felony convictions, as a priority, while continuing to enhance the technological capacities for detection of unauthorized crossings at the border.

Policymakers would be wise to separate out concerns about illegal immigration, which occurs primarily between ports of entry and is dropping, from those about organized crime and drug trafficking, which overwhelmingly use ports of entry to traffic illegal narcotics, cash, and weapons — and by all appearances have not abated. This concern argues for a renewed focus on border enforcement at ports of entry, rather than between them, but by using risk management techniques and investments in technology and infrastructure that make these ports both safer and more efficient, as is argued in the chapter on border management in this report.

The U.S. and Mexican governments will also need to have a sustained conversation about procedures for deporting migrants who are returned to their country of origin. In the past, the two governments have reached agreement on interior repatriations, which allows migrants to be flown into the interior of Mexico, nearer their hometowns. This has the advantage of discouraging repeated attempts at crossing the border and avoiding a large concentration of unemployed returnees in border cities, where they become prey to the efforts of criminal groups to recruit them.

Of course, a change in economic fortunes on either side of the border could reignite migration, but it seems increasingly unlikely since Mexican migration has only continued to drop since 2007. It is likely that the financial crisis served as a tipping point in the migration relationship between the two countries, while long-term structural changes have helped preserve this shift. Like Ireland, Italy, Germany, and other countries that once went through long periods of intense out-migration, Mexico may simply have reached the point where migration has ceased to be a necessary escape valve for a weak labor market.

This is not to say that all is well in the Mexican economy or that Mexican migration will cease completely. As long as gross domestic product (GDP) per capita in Mexico is more than four times lower than it is in the United States, there will be a reason for some Mexicans to move north, whether with legal visas or not. But slow and consistent economic growth in Mexico, together with a rapid expansion of education and health care availability, have created greater opportunities for those who stay.

The U.S. Congress has attempted to address unauthorized immigration — which is not Mexico-specific — through a three-pronged approach that would create new legal visas, regularize the status of those in the country who have established community ties, and provide enhanced border security and interior enforcement. To date, these efforts have failed, and it appears doubtful that this will be attempted again any time soon. This opens up possibilities for new kinds of thinking for how to address this issue, such as those laid out in influential reports from the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) and the Migration Policy Institute (MPI).

One recent report from a high-level task force convened by the Center for Global Development suggests that increasing legal visas for Mexicans, in particular, would help reduce the flow of unauthorized workers substantially, and past evidence suggests that even modest increases in temporary visas for work do reduce these flows. In the past, both Republican and Democratic administrations have expanded existing visa categories to accommodate additional workers, which appears to have contributed to the drop in unauthorized immigrants from Mexico, and additional categories that are more flexible might achieve this same purpose.

Many young Mexican immigrants who came to the United States as children have become eligible for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), which now provides more than 800,000 young immigrants, roughly 77 percent of them Mexicans, with the ability to remain legally in the country and to attend school or work. President Donald Trump has indicated that he would like to end this program, which he argues skirted existing laws and was an overreach of presidential authority, and his administration and legislators would do a great service by finding a more permanent legislative solution for these young people who came to the United States as children and know no other country but this one.

Unauthorized Mexican migration to the United States will remain a politically sensitive issue for the future, but the reality on the ground has shifted dramatically and policies will have to catch up quickly. While the U.S. government has good reasons to invest in border security and interior enforcement to ensure that existing laws are respected, it also has equally good reasons to ensure fluid cooperation with Mexico on Central American migration, help Mexico strengthen its economy, and find creative ways to expand legal flows.

Central American Migration

The number of Mexican migrants has dropped dramatically, but the number of Central Americans migrating to the United States through Mexico has increased dramatically. Many of these migrants come as full family units or are composed of unaccompanied minors, fleeing not only extreme poverty but also rising violence in El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala (figures 6 and 7). While overall flows across the U.S.-Mexico border still remain far lower than experienced a few years ago, this sudden spike has focused renewed attention on the border and contributed to a new public backlash against immigration in some parts of the United States. It has also taxed scarce resources for housing and adjudicating the cases of minors, who require special protection, and raised humanitarian concerns about the fate of minors who suffer severe mistreatment on the journey from their home countries, especially in Mexico. Many school districts have also faced strains as a result of the sudden influx of students with limited English skills.

Figure 6. Apprehensions at the Southwest Border by Type

Figure 7. Unaccompanied Minors Apprehended at the Border by Country of Origin

The U.S. and Mexican governments have worked closely to try to stem the tide of Central American migrants. Indeed, the number of apprehensions of Central Americans in Mexico has skyrocketed, with U.S. know-how, equipment, and funding underpinning what both governments call “The Southern Border Strategy” (figure 8). In fact, in 2015, more Central Americans were deported by the Mexican government than by the U.S. government, reducing pressure on the U.S.-Mexico border. If the U.S government hopes to preserve this cooperation, which has raised concerns in Mexican public opinion, it will have to work carefully with the Mexican government to craft the parameters of this cooperation. Meanwhile, the Mexican government will need to ensure that greater enforcement takes place in the context of rule of law, with full respect for the rights of the increasing number of immigration detainees in Mexican territory.

Figure 8. Central American Immigrants Deported/Returned by Mexican Authorities

One prong of the strategy to stem the flow of migrants from Central America has been to try to determine those who have legitimate asylum claims before they leave their home countries. The U.S. government also has begun receiving some asylum applications in Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador, although this is currently limited to those who have immediate family members already in the United States. It would also be worth considering whether the two governments could work together, possibly with the UNHCR as a partner, to adjudicate asylum claims in Mexico’s southern border region as well. This would require building a legal and physical infrastructure to process claims of migrants detained in southern Mexico to see if they have legitimate asylum claims and could be placed in either the United States or another country willing to resettle them.

Finally, both Mexico and the United States have an interest in addressing the underlying conditions of poverty and extreme violence that are leading people to abandon their home countries in Central America.

Americans in Mexico

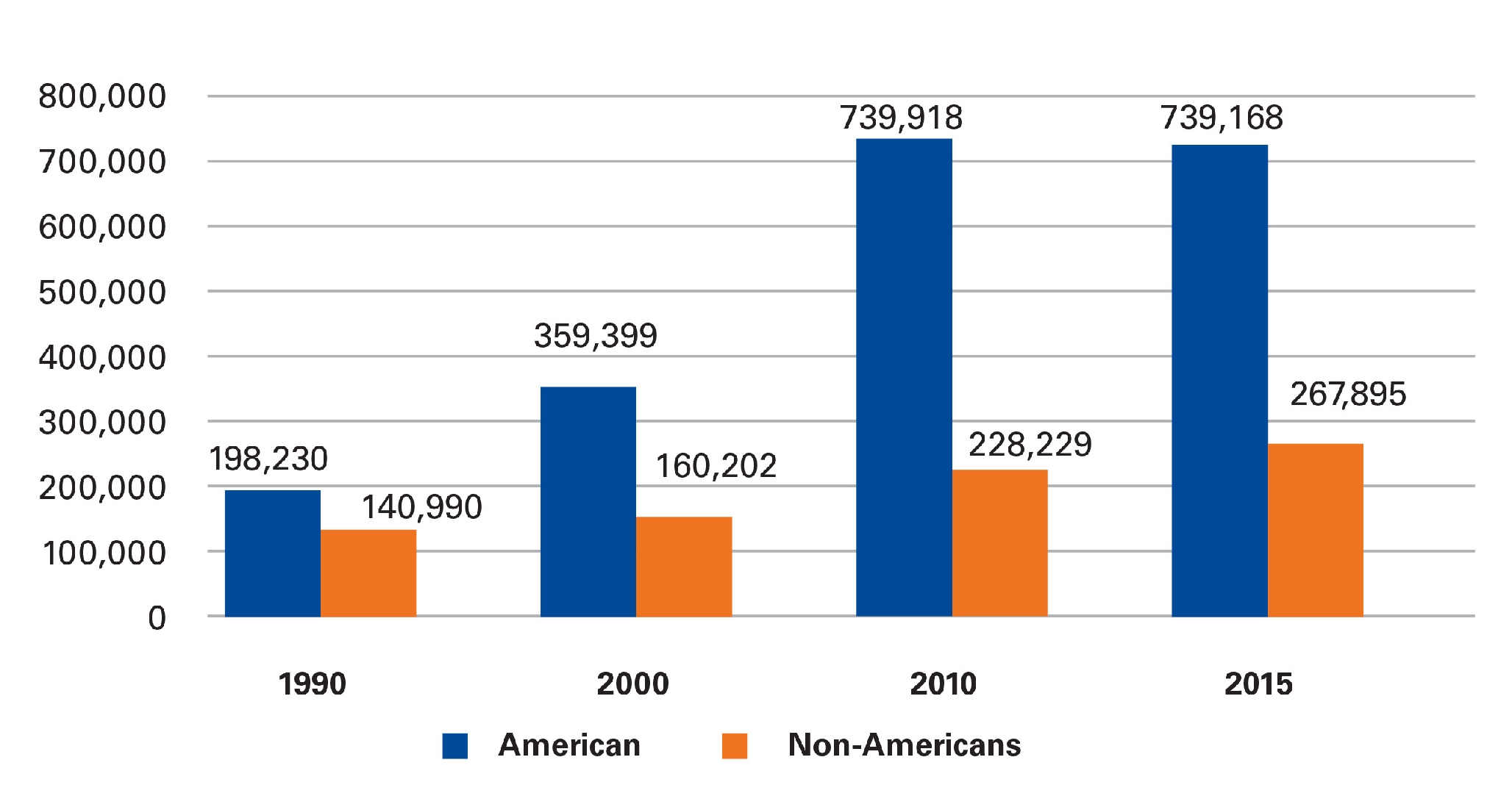

The U.S. Department of State estimates that there are roughly a million Americans in Mexico, and the Mexican population bureau puts the number slightly lower at 739,168 out of slightly more than a million foreign-born. Americans comprise roughly three-quarters of all immigrants in Mexico, and they are geographically distributed throughout the country (figure 9). Ironically, only a few of these U.S. immigrants have applied for legal residency in Mexico; technically, most are unauthorized immigrants.

Figure 9. Immigrants in Mexico

At least half or more of these immigrants are almost certainly children and spouses of Mexicans who have returned to their country of origin. According to the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (National Institute of Statistics and Geography; INEGI), most returnees have come back of their own free will, though a substantial number have been deported with family members following them. These U.S. citizens (especially children) often have Mexican heritage and speak Spanish at home, but they are usually culturally and educationally American, and they come up against both personal and logistical barriers integrating into life in Mexico. These range from discrimination against children who do not speak Spanish perfectly to difficulties in registering for school or for local services because they have only U.S. birth certificates and school documents, which are not always accepted by Mexican local governments and school systems. Many college-age students with only U.S. high school certificates, for example, find that they cannot apply to public universities in Mexico.

There are also two other sets of Americans living in Mexico — those who moved there for work opportunities and those who moved there for retirement. These groups, which together number several hundred thousand people, are more geographically concentrated in major cities and a in a few regions that have become magnets for retirees and self-employed Americans, including the Lake Chapala region of Jalisco, San Miguel de Allende in Guanajuato, Puerto Vallarta in Nayarit, and several border cities, including the coastline of Baja California.

There will be an increasing need for U.S. consular services to address basic needs of U.S. citizens living in Mexico and a growing flexibility of Mexican local authorities to adapt their practices to a growing immigrant population. Mexico has rarely thought of itself as a country of destination for migrants — with the partial exception of temporary flows of refugees from Central America in the 1980s and of small flows of refugees from Spain and South America in earlier periods — but increasingly, it is a country that is receiving a large number of immigrants from abroad and needs to be able to adjust policies, especially in education and health care, to address these new populations.

Conclusion

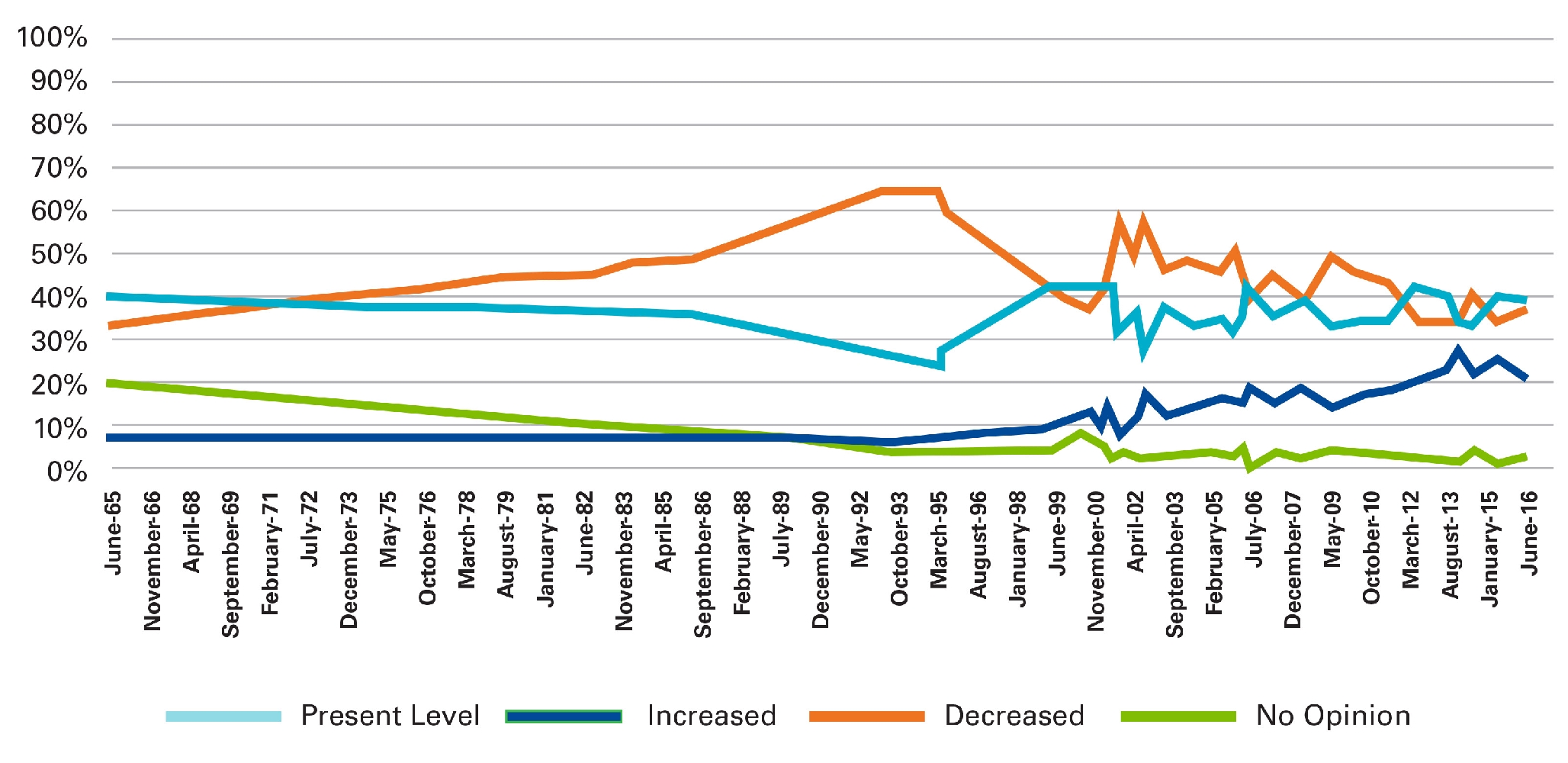

The public debate in both countries will likely be dominated by the issue of Mexican migrants to the United States for the foreseeable future because of political sensibilities in both countries. Nevertheless, public polls show immigration declining over time as a source of concern among Americans (figure 10), and even the recent presidential elections polls suggest that 70 percent of Americans would prefer to legalize rather than deport those who are in the country illegally.

Figure 10. Public Opinion on Immigrants to the U.S.*

*Thinking now about immigrants - that is, people who come from other countries to live in the United States, in your view, should immigration be kept at its present level, increased or decreased?

The government-to-government agenda, while continuing to focus on Mexican migration to the United States, increasingly will also have to pay attention to Central American migration through Mexico, which requires cooperation between the two neighboring countries, and to the large number of Americans migrating to Mexico. Over time, this will create a more nuanced and balanced migration agenda between the two countries, where cooperation is more useful than conflict and where interests converge in a way that would have been unthinkable a decade and a half ago. However, this shift will take time to develop, and there may be initial conflicts about migration policies before both countries realize their need for greater cooperation.

The United States and Mexico each have interests in protecting their sovereignty and enforcing their immigration laws, but they also will need to work together to address Central American immigration, ensure robust growth in Mexico that keeps migration from starting up again, and protecting their own citizens living in the other country.

The author would like to thank to Ana Isabel Abad Bagnasco and Miguel Toro for research assistance.

Andrew Selee was named executive vice president of the Wilson Center in January 2014. Prior to this position, Selee was the Wilson Center’s vice president for programs and the founding director of the Center’s Mexico Institute from 2003 to 2012.