Winter 2017

The Mérida Initiative and Shared Responsibility in U.S.-Mexico Security Relations

– Eric L. Olson

How a longstanding initiative has shaped cross-border cooperation

The election of Donald J. Trump as president of the United States opens a new era in U.S.-Mexico security cooperation. It is still unclear whether the framework of “shared responsibility” that has guided security cooperation between both nations will be deepened and strengthened, as it has been over the past decade, or is completely overhauled. By looking at the bilateral security relationship in its most recent historical context and seeing how it has evolved beyond the original “Mérida Initiative” set out by Presidents George W. Bush and Felipe Calderón Hinojosa, it is possible to see a number of options for building on and improving this relationship.

The safety and security of the United States and Mexico have always been intertwined. Nevertheless, suspicions based on historic conflicts; skepticism, and distrust on both sides of the border, as well as effective neglect by both governments, left their security cooperation mostly as an afterthought throughout much of the 20th century. The United States was often frustrated with what it saw as Mexican inaction against drug traffickers, with seeming tolerance for elevated levels of corruption and penetration of the state by criminal interests and a lack of systematic and robust focus in confronting drug traffickers. For its part, Mexico often felt blamed and victimized by crime and corruption that resulted from criminal groups seeking to supply a vast consumer market for illicit drugs in the north. Mexico felt pressured to deal with a problem that they viewed as largely in the United States, and pointed to U.S. failure to reduce consumption and better regulate access to firearms as the source of many of Mexico’s own problems with corruption, violence, and impunity. Not until the early 21st century, when escalating violence and the undeniable impact of transnational organized crime on the safety and well-being of all Mexicans became apparent, did both countries seek to define a policy of “shared responsibility” and mutual action to address these challenges.

The new security framework hammered out between the Felipe Calderón and George W Bush governments in 2007 became known as the “Mérida Initiative,” after the Mexican city where the framework agreement was signed. The initiative has been consistent in its commitment to a shared approach to addressing common security concerns, but it has not been static. It has evolved and expanded during the subsequent Obama and Peña Nieto administrations. Each successive government has added its own emphasis to the relationship, which now includes a robust framework for dialogue on multiple security fronts despite decreasing monetary commitments from the United States. With the new Trump administration, the security relationship is likely to be further reviewed and modified. The question is whether it will continue to deepen or experience a reversal to the more distant relationship of the past.

Origins of the Mérida Initiative

Although the U.S.–Mexico security relationship stems back many years, it had entered a particularly turbulent time during the mid-eighties and through the end of the next decade. The murder of DEA agent Enrique “Kiki” Camarena in Mexico in 1985 and the 1997 downfall of Mexico’s then-drug czar for connections to trafficking organizations were two major stumbling blocks. Efforts in the U.S. Senate to “de-certify” Mexico for failing to cooperate with the United States on counternarcotics efforts further exacerbated an already tense relationship.

Mexico also began to experience an uptick in crime-related violence in the later part of the nineties and the first years of the new millennium. Some of the violence occurred as a result of Mexico’s changing political landscape and the disintegrating centralized control of the long-ruling Partido de la Revolución Institucional (PRI). Shifts in international drug trafficking routes away from the Caribbean and into Mexico were also a factor.

Between the mid-1990s and the mid-2000s, Mexican criminal organizations and traffickers became major international players, often replacing Colombian organizations as the main buyers, transporters, and distributors of cocaine into the United States. What had once been primarily a Mexican marijuana trafficking business now became a lucrative transnational criminal enterprise that could move large quantities of cocaine and other illegal drugs into the United States. With major increases in the power and influence of Mexico’s organized crime groups, conflicts over routes and control of territory became a driving force behind shocking new displays of brazen criminal violence.

In the aftermath of a tightly contested presidential election in July 2006, Mexico’s President-elect Felipe Calderón reportedly became convinced that his country faced a dire situation in which the power and violence of criminal networks were threatening national security and stability. At the time, government action against criminal groups was less focused and aggressive than many thought necessary. Calderón’s alarm was so great that, according to an account by Alfredo Corchado in the book Midnight in Mexico, during his inaugural meeting with President Bush he raised the possibility of greater U.S. collaboration and support for his plans to confront criminal organizations: “I’m ready to do my part,” he said to Bush, “but I need a partner.” This initial conversation was the impetus for developing the shared responsibility framework that eventually became known as the Mérida Initiative.

Original Focus on the Mérida Initiative

According to a Congressional Research Service (CRS) report, the Mérida Initiative was designed to combat drug trafficking, transnational crime, and terrorism:

<BLOCKQUOTE>

The Mérida Initiative, as it was originally conceived, sought to (1) break the power and impunity of criminal organizations; (2) strengthen border, air, and maritime controls; (3) improve the capacity of justice systems in the region; and (4) curtail gang activity and diminish local drug demand. Initial funding requests for the Initiative focused on training and equipping Mexican security forces.

<BLOCKQUOTE>

Both the U.S. and Mexican presidents described the initiative as an attempt to “expand bilateral and regional counternarcotics and security cooperation.”

In the months following the joint announcement in Mérida, officials from both countries met behind closed doors to craft the details of the initiative. The results were presented publicly for the first time when President Bush requested from Congress $1.4 billion over three years to support the initiative beginning in fiscal year (FY) 2008. Thomas Shannon, then assistant secretary of state for Western Hemisphere affairs, described the Mérida Initiative as an “urgent” aid package composed largely of equipment and training that could have “an immediate and important impact in the fight against organized crime.” Ultimately, most U.S. legislators agreed to support the new plan, though the initiative was never put to a vote in the Mexican Congress.

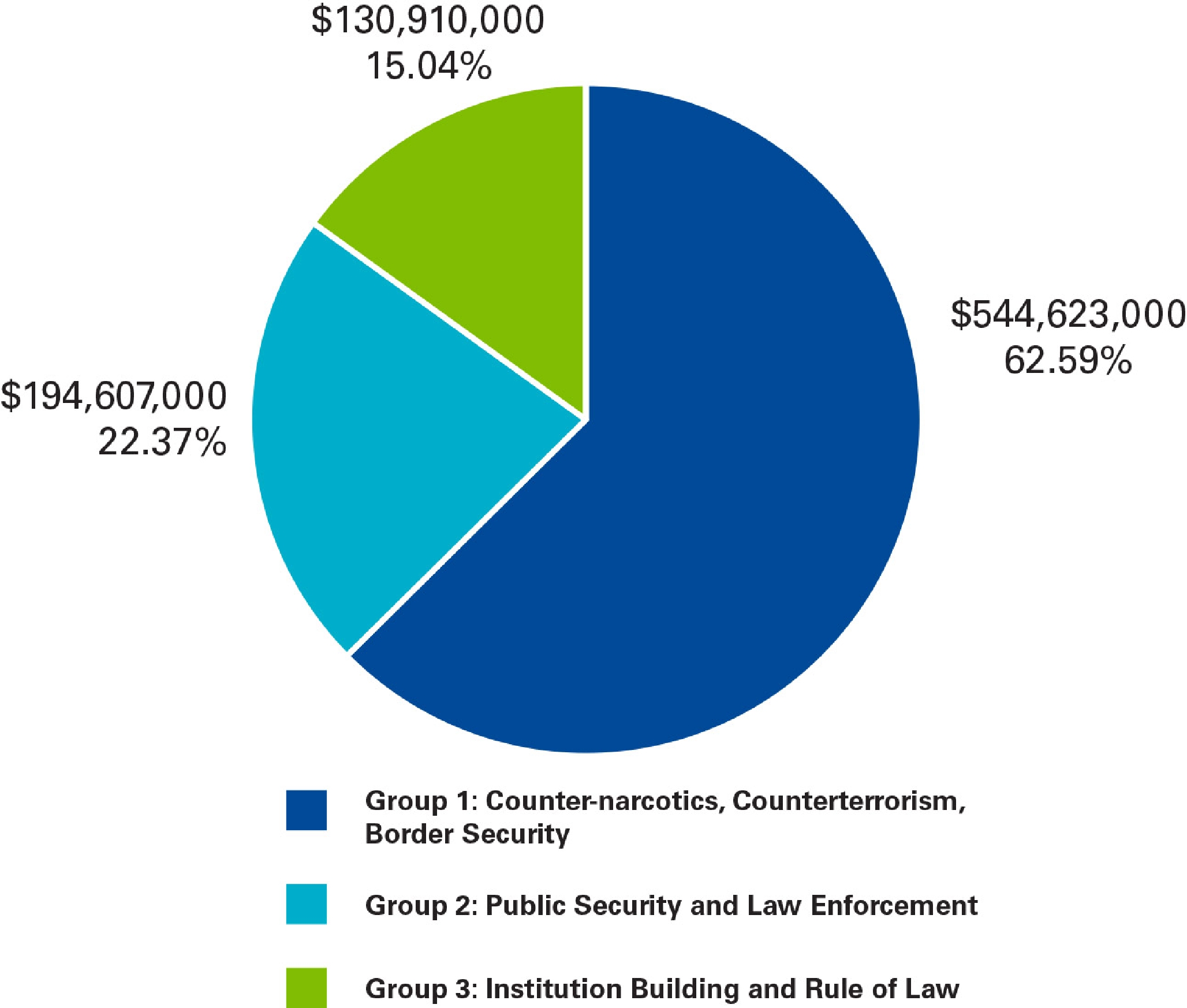

The Bush administration’s original proposal involved three broad baskets of assistance (see figure 1). The first and largest included counternarcotics, counterterrorism, and border security assistance, and represented roughly 63 percent of the administration’s budget request. It also included such high-priced items as fixed- and rotor-winged aircraft for use by Mexican security forces. The second basket was primarily for public security and law enforcement programs, including training, technology, and information management programs to improve the capacity of Mexico’s civilian law enforcement agencies and support their modernization. This group was roughly 22 percent of the administration’s overall request. The third and final basket included programs related to institution building and rule of law promotion, such as including support for Mexico’s judicial reform process, the strengthening of human rights, and programs to combat substance abuse in Mexico. This group was roughly 15 percent of the funding request.

Figure 1. Bush Administration Requests for Mérida Initiative

The announcement of such close security cooperation with the United States generated some controversy in Mexico, where questions were once again raised about national sovereignty and the extent to which U.S. law enforcement, military, and intelligence personnel would be operating in Mexican territory and whether they would be armed. Moreover, questions were raised about the program’s heavy emphasis on hardware. By placing greater emphasis on aircraft, scanners, and X-ray technology, it emphasized a traditional coercive approach to combating drugs. The need for institutional reforms in the justice system and a stronger institutional capacity of law enforcement agencies to conduct investigations and combat crime was a lesser priority.

Additionally, while the presidents and cabinet secretaries of both countries were involved in the “shared responsibility” approach of mutual support and bilateral collaboration in confronting a common enemy, the traditional language of foreign assistance and aid to Mexico reemerged in the U.S. Congress and press in a way that seemed to undermine the original purpose. Was the Mérida Initiative simply the United States “helping” Mexico combat organized crime as it had helped Colombia battle armed groups and drug traffickers? Or was this a different model, whereby a common enemy is confronted jointly with each side assuming its own responsibilities for action? More important, public commitments by U.S. officials to disrupt firearms trafficking, crack down on money laundering and bulk cash transfers across the southwest border, and renew efforts to reduce consumption of illegal drugs in the United States were not tied to specific targets or funding initiatives. As a result, there were doubts about how serious the United States was at addressing its own responsibilities in the struggle against criminal groups.

Adding to the controversy was the U.S. Congress’s insistence that the funding package include human rights language, further infuriating Mexican authorities that wanted to avoid the appearance of being “certified” by the United States on human rights grounds. The final 2008 funding package required the State Department to report to Congress on specific steps that Mexico would take to address human rights concerns. The areas to be reported on included efforts to improve local, regional, and national police transparency and accountability; consultations with Mexican human rights and civil society organizations; work to ensure civilian-led investigations of alleged human rights violations; and the prohibition on the use of testimony obtained through torture. Despite doubts expressed in both countries, the U.S. Congress released a first installment of $400 million in Mérida Initiative money for Mexico in 2008, and though U.S. legislators initially delayed the second installment in 2009 due to human rights concerns in Mexico, the Obama administration remained supportive of the policy.

Although the early focus of the initiative was mostly on budget and program elements, the plan also called on intelligence, counternarcotics, and law enforcement forces in both countries to work together. Many of the agencies had developed extensive relationships with their cross-border counterparts prior to the initiative, but cross-border interagency coordination was infrequent. A major concern was that these relationships could be weakened and intelligence information could be leaked when shared with a broader set of agencies. Nevertheless, according to Sigird Arzt, former National Security advisor to President Calderon, once the coordination plans and ground rules were clarified and the agency heads were convinced that operational information would not be put at risk, all participants understood the roles they could play to improve efficiency in the fight against organized crime.

The Evolution of Mérida under the Obama Administration

The arrival of the Obama administration in 2009 was an important opportunity to reconsider U.S. security assistance with Mexico. With a new Democratic Party majority in Congress (elected in 2006) it could have been an opportunity for the Obama team to dramatically cut back on the Mérida Initiative, which by then was in the final year of the original three-year budgetary commitment. Nevertheless, the Obama administration decided to rethink and reorient some of the strategy but not dramatically alter it. Led by then U.S. Ambassador to Mexico, Carlos Pascual, the administration gave the security relationship a new modified framework with new elements, which took shape around four strategic priorities, or “pillars” (see figure 2).

Figure 2. The Four-Pillar Framework

The four-pillar strategy combined short- and long-term approaches to addressing the security concerns posed by organized crime. Short-term collaborative efforts focused on improving intelligence collaboration to dismantle criminal networks, arrest their leaders, and intercept the southward flow of money and weapons. These strategies were laid out in the first two pillars. Two additional elements of the Mérida Initiative’s reformulation included a greater focus on border and violence prevention. Pillar 3 introduced the “21st century border” initiative, and Pillar 4 sought to refocus efforts to “build strong and resilient communities” in Mexico that could better resist and prevent violence.

Support for border security (Pillar 3) has long been a U.S. policy priority and was very much a part of the original bilateral security strategy. The focus, however, was primarily on the U.S.–Mexico border where the United States was concerned about “spillover violence” from Mexico’s trafficking organizations as well as possible terrorist threats aided by insufficient border security. Over time, these two concerns proved to be less pressing as violence was not “spilling over” from Mexico to the United States in significant amounts — U.S. border cities are some of the safest in the country — and no publicly known terrorist attack in the United States has used Mexican territory as an entry point.

During the Obama administration, the border security framework shifted to a border management strategy that sought to balance security, commerce, and human movement by using the tools of “risk segregation.” Rather than viewing every migrant or cross-border commercial shipment as a potential threat, greater emphasis was placed on separating the risky from the ordinary. To do so, greater emphasis was placed on prescreening programs such as trusted traveler or trusted shipper programs that enabled those who were precleared to move across the border with greater ease. Such preclearance programs not only benefited frequent travelers and shippers but also allowed border and customs authorities to spend less time examining low-risk entries and refocus their energies and resources on unknown, potentially more risky entries.

The final pillar, with its focus on building strong and resilient communities, called for a comprehensive approach to violence reduction through prevention programs. It is a significant evolution of the original Mérida Initiative vision from a primarily security-based approach to a social preventative approach. The original focus points of the Pillar 4 efforts were in three of Mexico’s most dangerous cities: Tijuana, Ciudad Juárez, and Monterrey. These efforts included the creation of violence reduction programs with civil society’s input and collaboration that helped improve public spaces, create jobs, and try to reduce demand for illegal drugs.

The Peña Nieto Period

The presidential campaign leading to the 2012 election of Enrique Peña Nieto was notable in one important regard: Mexico’s security crisis, while constantly present in the minds of many Mexicans, was not the centerpiece of the electoral contest. As a candidate, Peña Nieto successfully converted the election into a referendum on 12 years of PAN rule, arguing that he represented a new, more modern PRI that could govern more effectively and efficiently than any other party. He promised better policy coordination on security issues within the federal government and between local, state, and federal authorities.

The centerpiece of this argument was what the Peña campaign characterized as the underperforming and inefficient Mexican economy, which he promised to restore to robust growth with numerous market-friendly reforms. He also made the case that it was time to turn the page on Mexico’s security challenges, and place these in the context of Mexico’s enormous economic promise and potential. The campaign saw no focused debate on security policy, and Peña Nieto did not present a comprehensive alternative to Calderón’s policy of aggressive confrontation. He simply rejected the Calderón strategy as ineffective and one which produced elevated levels of violence, widespread fear, and growing distrust of government. Instead, he promised a plan consisting of four goals: to reduce violence, to transition the military from its public security functions while standing up a specialized police force he called a “gendarmerie,” to prioritize prevention programs, and to more effectively coordinate all aspects of the new security strategy.

Furthermore, neither the PAN’s Josefina Vázquez Mota nor the PRD’s Andrés Manuel López Obrador were inclined to engage in this kind of debate. Vázquez Mota did not want to break entirely with Calderón by offering a dramatically different approach to improving public security and combating organized crime, preferring instead to suggest modifying existing policies. She also recognized that the public was overwhelmed by the violence that had erupted during the Calderón years, so a full embrace of the Calderón legacy was not politically viable. López Obrador offered critiques of the Calderón strategy, suggesting that problems of violence and organized crime reflected underlying problems of poverty and inequality. He suggested that his approach would prioritize creating economic opportunity for at-risk youth and greater support for prevention programs. Ultimately, it was difficult to distinguish the López proposals from those of Peña Nieto. And if security strategy was not a focus of Mexico’s presidential campaign that year, then U.S.-Mexico security cooperation was even less so.

So it came as a surprise to U.S. officials and analysts when in the postelection period the Peña Nieto government signaled that it wanted a pause in the security cooperation agenda to give the new team a chance to assess the status of bilateral cooperation. Based on personal interviews with those close to the new government, several expressed concern that Mexico had lost control of the cooperation agenda, that the Calderón government had been too hands-off in coordinating the relationship, and that “collaboration” was taking place outside of the normal channels and without the knowledge of a central coordination point within the Mexican government. The example most cited in this regard was the August 2012 armed attack on two alleged CIA agents traveling with Mexican naval officers south of Mexico City. Their vehicles were assaulted by numerous federal police believed to be working for an organized crime network. What was particularly alarming, even galling, to those close to the Peña Nieto government was that the CIA agents reportedly were operating with Mexican naval personnel without the knowledge of civilian authorities. The existence of broad cross-national cooperation without centralized control and coordination was particularly alarming to many in Mexico’s Secretariat for External Relations (SRE) and among Peña Nieto’s incoming political and security advisors.

As a result, one of the first major announcements related to Mexico-US security cooperation from the Peña Nieto government was intended to improve bilateral coordination on security matters. In preparation for a visit to Mexico by President Obama in May 2013, Peña Nieto’s new interior minister, Miguel Osorio Chong, announced the government would present President Obama with its new security plan including improved coordination through a “ventanilla única” or single coordinating office within the Secretariat of the Interior (Secretaria de Gobernación; SEGOB). Secretary Osorio reportedly said, “[This) is the order that is being given to the (bilateral) relationship through the Secretariat of the Interior. Agencies will not be allowed to determine with whom they are collaborating. That is how it was being done before.” He added, “Now there is only one channel, the Secretariat of the Interior, and from there, we can engage in orderly cooperation so that efforts aren’t duplicated.” Yet in spite of its good intentions, the new policy had the immediate effect of freezing many ongoing collaboration efforts. The message to Mexican security forces was that continued and new collaboration had to be cleared first through the central point of the Secretariat of the Interior, so many agency plans ground to a halt as they sought to ensure full coordination and ultimately approval from the coordinating office.

Many U.S. officials, although concerned about the situation, sought to portray this process as a normal transition between governments, with the new one seeking to assess the full nature of its existing security relationships and evaluate its priorities going forward. Nevertheless, U.S. officials also expressed alarm privately when the process took longer than expected. Peña Nieto’s governing priorities were elsewhere, including on significant energy sector and educational reforms, and his desire to change the narrative about Mexico’s security challenges likely resulted in a slower approach than many in the United States had expected or wanted. The United States was willing to support Peña Nieto’s pivot to an economic agenda, and certainly supported the new government’s efforts to modernize its energy and education sectors, but it did not want its anti-drug operations to be squandered and pressed the Peña Nieto government to continue those programs.

Ultimately, the collaboration agenda got back on track later in 2013 and early 2014 with a series of high-profile operations, arrests, and assassinations of cartel leaders. Many of these benefited from U.S. intelligence assistance, including the February 2014 capture of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán Loera in the Pacific resort town of Mazatlán. Such a spectacular capture signaled two important things to Mexico: that the United States could be a trusted, responsible partner in a behind-the-scenes role providing important intelligence information and support, and that the capture of high-profile cartel leaders continued to be politically popular. It was not a strategy the Peña Nieto government was likely to jettison despite campaign rhetoric suggesting that it would take a new approach. What became increasingly evident to the U.S. and Mexican public was that the Peña Nieto strategy for dealing with trafficking organizations was not significantly different from that of the Calderón government, and the policy differences were more a matter of style and emphasis than substance.

By late 2013 and early 2014, U.S.-Mexico security cooperation was back on track, though it was no longer the primary issue that had been throughout much of the Calderón administration. In effect, Mexico ratified the “four-pillar” strategy articulated by the Obama government in 2009 and continued to collaborate in all four areas as the Peña government moved forward. Within the “four-pillar” Mérida strategy, four priorities seem to have emerged during the Peña Nieto years: promotion of rule of law, support for justice sector reform, border security, and crime prevention.

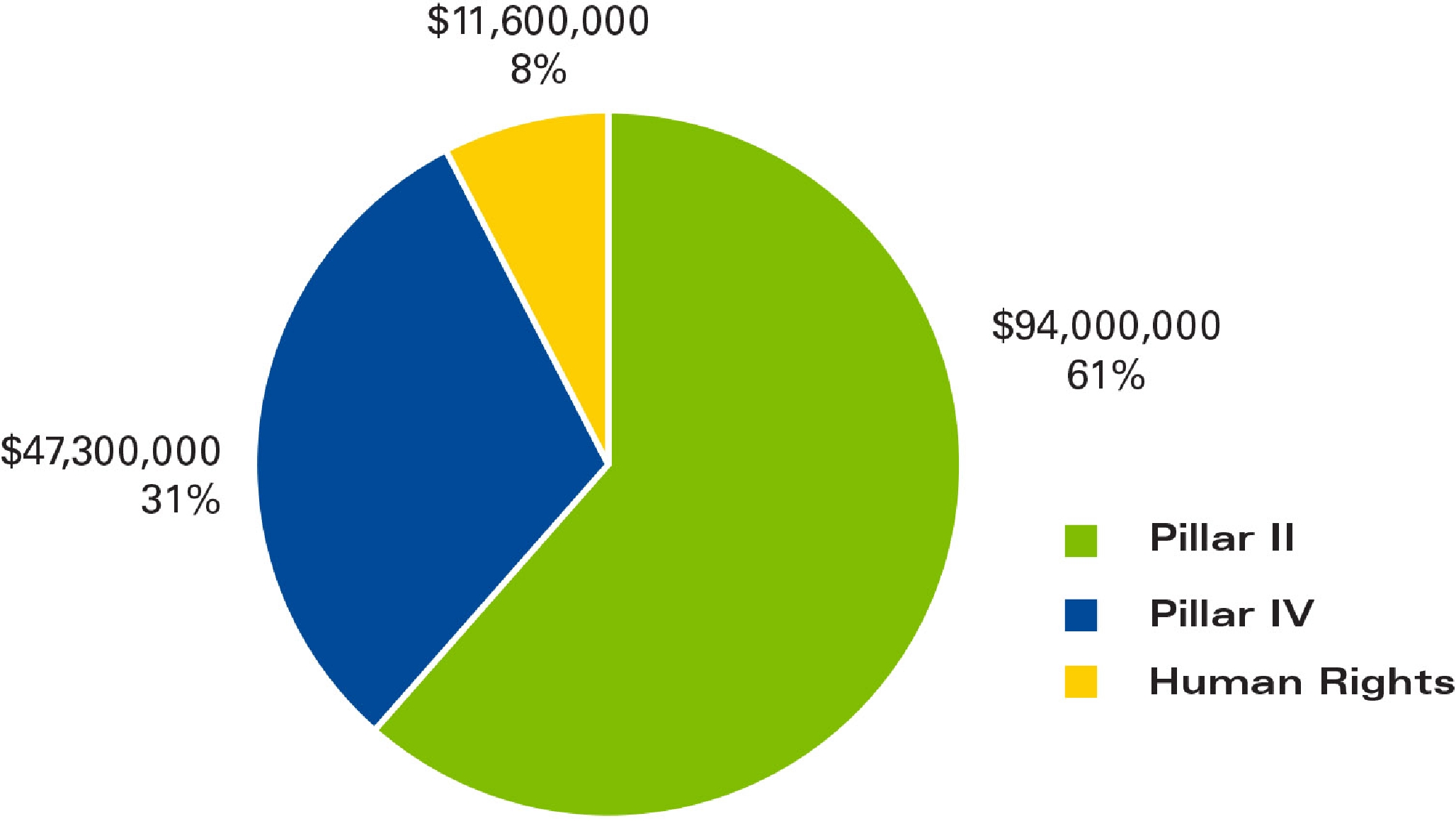

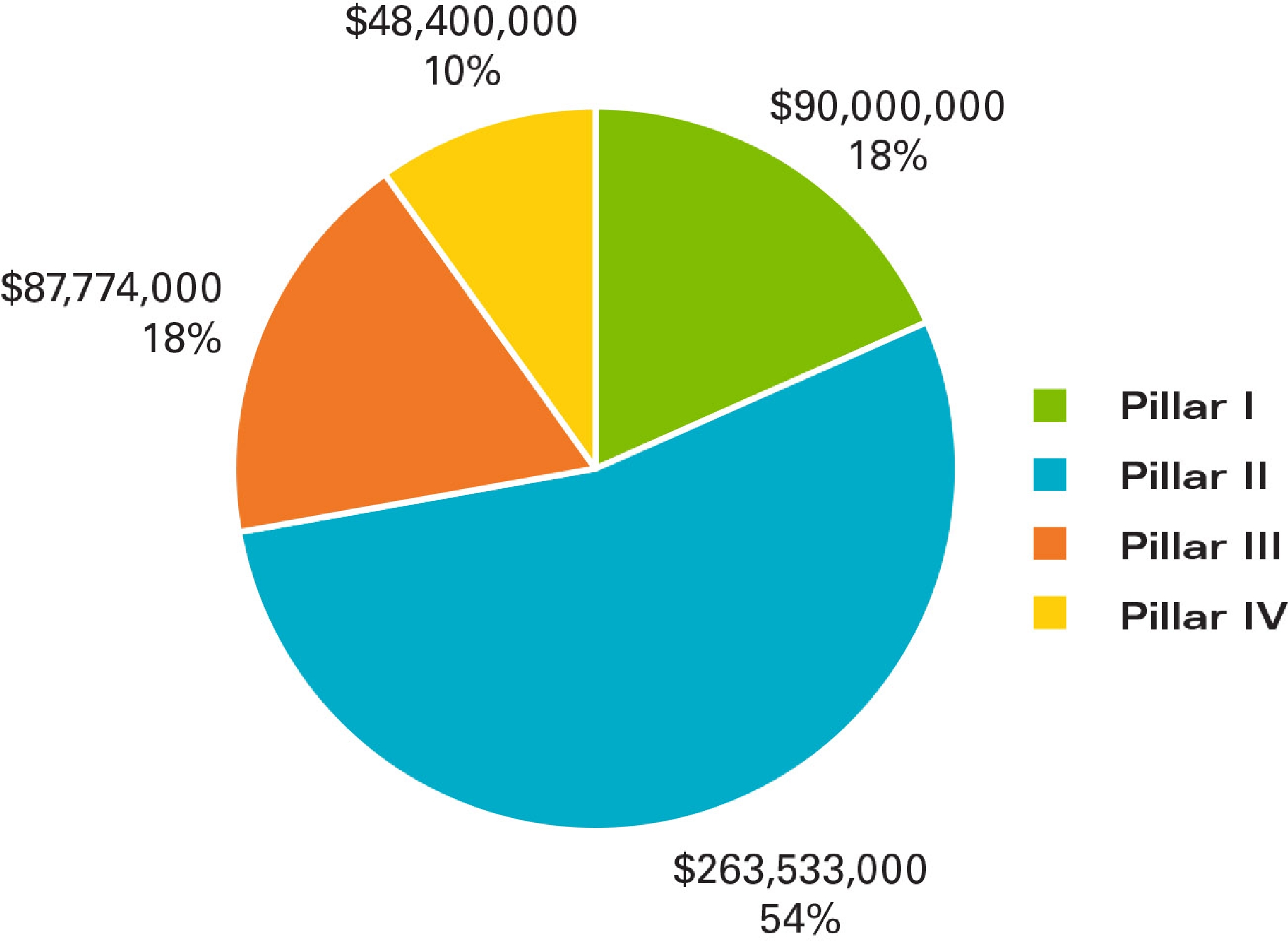

As can be observed in the charts below, funds for these programmatic areas come from two U.S. government sources: the State Department’s Bureau of International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement (INCLE) and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). The amount of assistance passing through the INCLE bureau is roughly four times greater than that passing through USAID. Regarding support for rule of law and justice sector reform, it is worth noting that both INCLE and USAID have devoted most of their funding to Pillar 2 (Institutionalizing the Rule of Law) programs since FY 2012, at 58 percent (INCLE) and 61 percent (USAID) respectively (see figures 3 and 4). In budget terms, this makes justice sector reform by far the largest single component of U.S. funding for the Mérida Initiative, and suggests a significant redirection of priorities for U.S. assistance since 2007.

Figure 3. USAID FY 2012–16 Total Mérida Initiative Funding

Figure 4. INCLE FY 2013–16 Total Mérida Initiative Funding

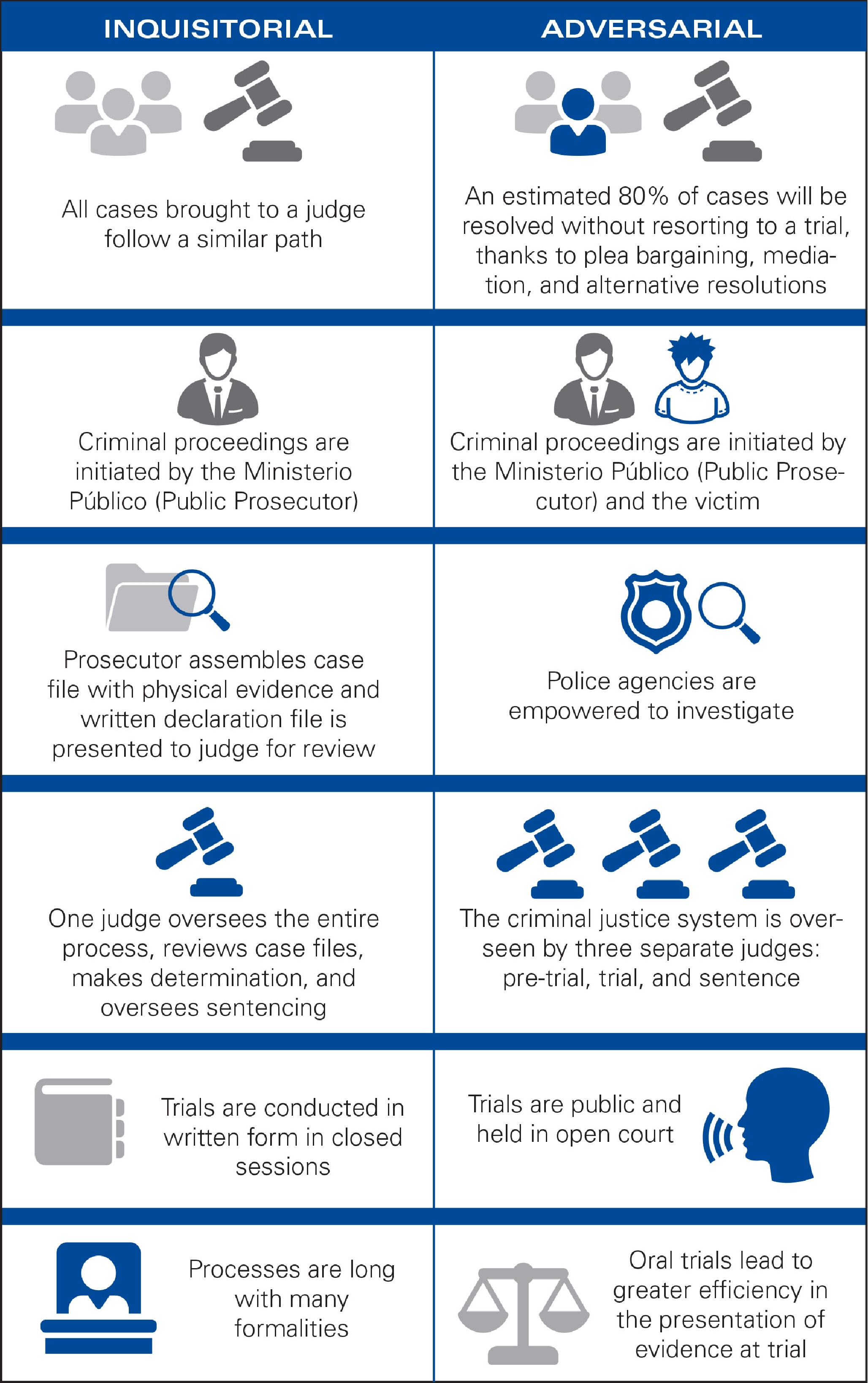

U.S. support for justice sector reforms has come in the form of three major projects implemented by a U.S. firm, Management Systems International, Inc. (MSI). The first of these programs, known as PRODERECHO (2004–7), predated the Calderón era’s constitutional and criminal procedure reforms, reflecting efforts by the Fox government to reform the criminal justice system. While Fox’s proposed reforms lingered in the Mexican Congress, preliminary technical legal studies and proposals supported by the MSI program enabled Mexican legal scholars to begin to develop what became eventual constitutional reforms, passed in 2008, that transformed Mexico from an inquisitorial to an adversarial criminal justice system (See the adjacent chart for a description of the two systems). Additionally, a significant portion of the PRODERECHO resources were for state-level reform efforts, especially in Chihuahua, one of the earliest states to adopt the adversarial criminal procedure reforms.

The PRODERECHO project was replaced by the Justice and Security program (2009–14). In this, case the goal and objectives were to support Mexico’s transition to an adversarial justice system that resulted from a 2006 constitutional reform. The Justice and Security program provided technical assistance, training, and expanding professional capacity within federal, state, and municipal law enforcement agencies to better align these with the new judicial system.

Finally, the PROJUST (Pro Justicia) program (2014–19), also managed by MSI, represents the U.S. flagship effort to support Mexico’s judicial transition. Worth roughly $3 million, it is approximately 10 percent of Mérida Initiative funds for judicial reform. All three projects represent a significant U.S. commitment to support Mexico’s judicial and institutional reform efforts and desire for a more effective and efficient justice system.

Support for border security (Pillar 3) during the Peña Nieto years has included U.S.-Mexico border improvements, as well as an expanded focus on Mexico’s southern border with Guatemala. Using the same Pillar 3 framework described above, the United States has increased its investments in Mexican and Guatemalan border areas to improve border infrastructure, force mobility, and security and immigration personnel. Additionally, funds have been used to provide new technology, such as “mobile bio-kiosks” to improve the processing of migrants. Investments in Mexico’s southern border have mostly taken place in the context of the Central American migrant crisis, which has resulted in tens of thousands of migrants fleeing violence and economic hardship in Central America’s Northern Triangle (El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras) seeking relief in Mexico and the United States. Increasing migrant flows and the relative ease with which organized crime groups can transit international boundaries such as the Guatemala-Mexico border has been a growing concern for U.S. policymakers for some time and reflects the increase in funding directed to southern Mexico.

The United States also quietly increased its prevention (Pillar 4) programming, in particular by expanded its support for projects originally focused in Tijuana, Ciudad Juarez, and Monterrey. As of 2015, USAID has used Mérida Initiative funds to support a project called “Juntos para la Prevención de la Violencia,” administered by the U.S.-based implementing company Chemonics International. The project’s primary objective to “contribute to strengthening the capacities of the different levels of government to design, implement, and evaluate public policies to prevent violence and crime.” To accomplish this objective, it has pursued three initiatives: establishing a network of cities engaged in youth prevention work; setting up a special funding mechanism (Fondo para la Prevención de la Violencia) to fund local prevention initiatives and encourage private sector investment in prevention projects; and establishing a Public Safety and Violence Prevention Laboratory to investigate, evaluate, and promote successful models of prevention.

Finally, the issue of human rights has become increasingly relevant to the relationship as Mexico has struggled with several high-profile, deeply troubling incidents of human rights violations. Two emblematic cases include the apparent massacre of approximately 12 civilians by army personnel in the city of Tlatlaya in June 2014. A second case involved the disappearance and presumed death of 43 students from a rural school in Ayotzinapa, Guerrero, in September 2014. In both instances, serious accusations of coverups by authorities were made in the aftermath of each case, and in the particular case of the 43 students, evidence of local police involvement and the use of torture for extracting confessions from alleged perpetrators is at the heart of the matter. These and other troubling cases of human rights violations by security forces has presented a challenge for U.S. assistance programs because the Leahy Law prohibits U.S. support for training and equipping foreign security force units when there is credible evidence of human rights violations.

In terms of the bilateral security agenda, human rights issues have been handled in two ways. First, with relation to the human rights criteria and reporting required of the Department of State by Congress, the secretary of state took the unusual and largely symbolic decision in October 2015 to transfer $5 million in counternarcotics assistance for Mexico to Peru. This action was needed to comply with a provision that Congress had included in the FY 2014 U.S. Foreign Assistance Act, stating that 15 percent of counternarcotics assistance to Mexico could be obligated only when the secretary of state provided a written report to the Congressional Appropriations Committees outlining Mexico’s progress in four human rights areas. While human rights reporting requirements have been standard since the Mérida Initiative began in 2008, the criteria were broadened with the 2014 funding bill. Congress added criteria requiring the secretary to report on steps taken by the Mexican government to enforce “prohibitions against torture,” promptly transfer military detainees “to the custody of civilian judicial authorities,” devote government efforts to search for the victims “of forced disappearances,” and investigate and prosecute those responsible.

According to a State Department official familiar with the issue, the Department was “unable to confirm that Mexico fully met all of the criteria in the FY 2014 appropriation legislation and thus did not submit the report (to Congress).” The State Department believed that Mexico had complied with earlier requirements, including those contained in the FY 2013 funding bill, and had taken significant legal steps, including instituting constitutional reforms to improve the legal framework for human rights, but had not reported sufficient progress related to the expanded criteria accompanying the 2014 legislation.

In response to the U.S. decision, Mexico’s secretary of foreign affairs reportedly said the following: “The U.S. government has recognized Mexico’s determination and progress to address particular human rights challenges. . . . Bilateral dialogue and cooperation are the appropriate ways to address the current challenges in this regard.” In effect, Mexico and the United States have started a separate “bilateral human rights dialogue” that brings together relevant government actors — security forces, attorneys general, and foreign ministries —to consider human rights concerns on both sides of the border. This group has met seven times to discuss human rights concerns in both countries and the government of Mexico would prefer that this become the primary forum for discussing human right issues, thereby avoiding potential embarrassments and sensitivities that arose with the decision to transfer U.S. funds to Peru.

Despite (or perhaps because of) the controversy surrounding several serious human rights cases, U.S. funding for human rights programming in Mexico has increased significantly in the past year. In particular, USAID has devoted approximately $8 million for human rights projects separate from its support for judicial reform and from the Mérida Initiative. One of the principal human rights programs supported by USAID is to be administered by Chemonics, the same firm implementing the new violence prevention programs. According to the Chemonics website, “The EnfoqueDH project is supporting the Mexican government to integrate human rights-based approaches in its legislative frameworks and institutional processes.” It aims to incorporate a human rights perspective within regulatory, federal, and state frameworks, and public servants and civil society stakeholders who also are advocating for human rights

The Future of U.S.-Mexico Security Cooperation

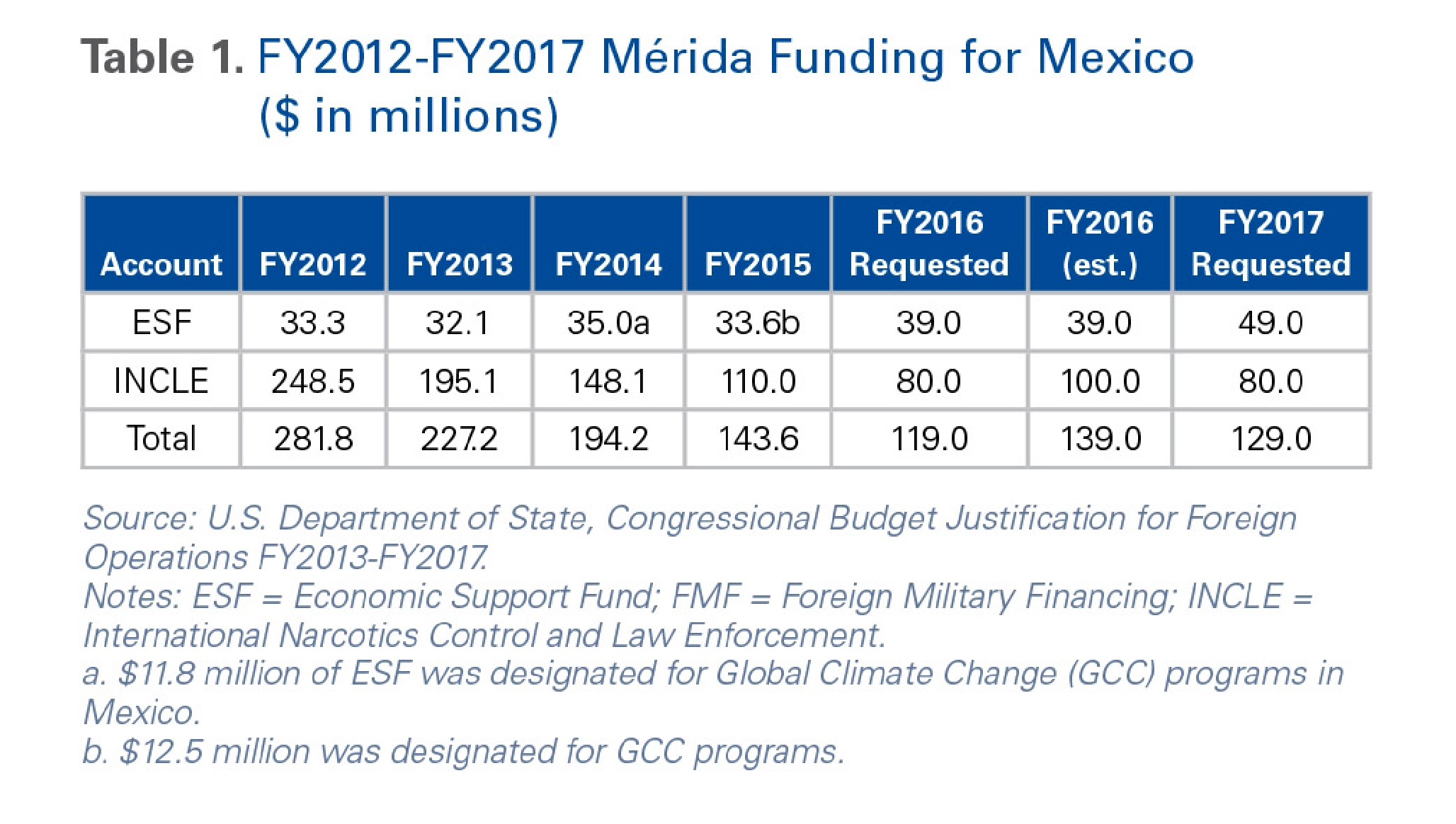

It is also worth noting that despite the importance the U.S. places on its security cooperation agenda with Mexico, the amount of money that Congress has approved for the Mérida Initiative has declined (table 1).

Such figures seem paltry in comparison to U.S. assistance for Central America, where President Obama requested $ 1billion in FY 2016 resources and Congress approved $750 million. Obama requested a second billion-dollar aid package for Central America for FY 2017, and Congress is likely to approve somewhere close to another $700 million. In this same timeframe, Mexico would have received roughly $268 million, or 80 percent less than given to Central America.

From one perspective, this might signal that Central American security is more important than Mexico’s to the United States, but nothing could be further from the truth. Instead it signals that the security relationship has moved beyond the Mérida Initiative assistance programs, heralding a new era of security cooperation. The current U.S.-Mexico security frame now extends to high-level strategic dialogue with a much broader agenda, more in line with the high-level economic dialogue already in place between both countries.

In effect, both the Obama administration and the Peña government decided to expand the security cooperation agenda when they established the Bilateral Security Cooperation Group (Grupo Bilateral de Cooperación en Seguridad; GBCS). According to the Secretariat of Interior: “The Bilateral Security Cooperation Group is the main high-level US-Mexico forum for the strengthening of strategies on issues that are of common interest. Also, it provides a strategic framework for coordination of security based on the principles of shared responsibility, mutual trust and respect for the sovereignty, jurisdiction and laws of both nations.” It addresses issues such as trafficking in drugs, weapons, and humans, money laundering, and smuggling. The GBCS also works to strengthen the rule of law and the professionalization of the police, all of which address concerns covered by the Mérida Initiative.

The expanded GBCS agenda was also confirmed in a White House communiqué following the July 22, 2016, meeting between Presidents Obama and Peña. The White House “Fact Sheet on United States-Mexico Relations” framed bilateral security cooperation in three areas: improving migration and refugee protection protocols, cooperation against heroin trafficking and poppy cultivation, and “Security and Justice Cooperation - Mérida Initiative.” The implication is that the security relationship has transcended the Mérida Initiative and are no longer constrained by a predefined programmatic agenda. As a result, the security relationship has evolved, matured, and is probably at its highest point in history.

Military-to-Military Relations on the Rise

Another element of the U.S.-Mexico security relationship is the military-to-military (or mil-mil) relationship, which occurs outside the immediate confines of the Mérida Initiative. As in the civilian realm, mil-mil relations have been hampered historically by mistrust and unfortunate and misguided military interventions by the U.S. during the first decades of the 20th century. More recently, as Iñigo Guevara Moyano has argued, mil-mil relations have also seen moments of significant collaboration and the current state of the relationship is at a high point.

The relationship mirrors many of the challenges of the growing civilian security relationship, but has by and large avoided public scrutiny and occurred within a limited scope of activities. The most important activities include training and expanded educational opportunities for the militaries of both countries, the transfer and/or sale of equipment, and simultaneous patrols along the northern border designed to improve communications and build confidence and trust. Nevertheless, Guevara argues, “Despite a rapprochement process that began in 2006 and remains ongoing in 2016, the U.S.-Mexico military relationship still has ample room for growth. . . . Bilateral trust needs to be a key goal for both militaries and once obtained, it needs to be constantly nurtured and reinforced . . . [it] is unfortunately not a commodity that countries can procure; it is rather the product of a well-planned investment strategy.”

Depending on the priorities and emphasis that the new Trump administration brings to the security relationship, the mil-mil component may provide the greatest opportunity for growth. Whether the new U.S. government continues the framework of shared responsibility or sets it aside to focus on other priorities, the mil-mil relationship likely will continue and strengthen regardless of activity in the civilian security relationship. What has the potential to undermine the relationship is an overly nationalistic, vitriolic, and ultimately unilateral U.S. border policy that will force the Mexican military, as well as the entirety of the Mexican government, to reevaluate the bilateral relationship or even become more defensive in its posture with the United States. Such a development would indeed be unfortunate.

Some Early Challenges for the Trump Administration

Since the framework of shared responsibility in security cooperation was established in Mérida in 2007, successive U.S. and Mexican governments have refocused or expanded the security relationship without fundamentally abandoning the concept of shared responsibility. A core rationale for this policy has been the belief that security in both countries is enhanced through cooperation rather than each country “going it alone.” From the U.S. perspective, issues such as border security are greatly facilitated and enhanced when both countries are not working at cross-purposes. And it would be impossible for the United States to influence the security agenda on the Mexico-Guatemala border without a cooperative Mexico. Furthermore, the delicate balance between security and preservation of the two countries’ economic, cultural, and social ties requires constant communication, coordination, and ultimately trust between government agencies on both sides of the border.

Conversely, a policy focused narrowly on security at the borders, or one based exclusively on counternarcotics operations, is likely to undermine the benefits of a fuller relationship and ultimately fail in its own traditional view of the war on drugs. Decades of the war on drugs has produced many outcomes. Some have been good, as brutal criminals have gone to jail. Others — like the mass incarceration of low-level nonviolent drug offenders; unacceptably high levels of violence; and, most important, the failure of the war on drugs to actually stop drug cultivation, processing, trafficking, and consumption in any country in the region — have been bad. These are the challenges that the Trump administration will face. Will it pursue policies that preserve the framework of shared responsibility and a cooperative security strategy? To adopt a cooperative agenda implies a U.S. willingness to continue investing in demand reduction efforts with greater emphasis on treatment options, and programs with a proven track record of reducing recidivism. It also implies taking serious steps to disrupt the flow of firearms south and new initiatives to make money laundering more difficult and more costly to criminals.

The history of security cooperation between the two countries has shown that coordination and collaboration are far more effective tools for enhancing outcomes than purely unilateral approaches. Such unilateral approaches would undermine the spirit of cooperation that has imbued the relationship for nearly a decade of Republican and Democratic administrations in the United States, and PAN and PRI governments in Mexico. Ultimately, the Trump administration will have to decide whether the United States is safer and its national security is better served by a collaborative or antagonistic relationship with Mexico.

Conclusion

The framework of shared responsibility first articulated in the context of the Mérida Initiative agreement between Presidents Bush and Calderón continues to provide the architecture for bilateral security cooperation between Mexico and the United States. But the range of issues addressed in the bilateral context, and the level of bilateral engagement and dialogue, is no longer limited to strict program areas from the Bush years and subsequent initiatives undertaken by the Obama administration. The bilateral security agenda has evolved, as it should, and is no longer confined to four pillars or any specific assistance program, regardless of their importance. Instead, it has created an institutional space for ongoing bilateral dialogue that can address new and emerging threats — a sign of the maturity of the relationship.

What is lacking from the current strategy is a framework for evaluating progress. Dialogue is taking place at the highest levels, intelligence and law enforcement cooperation continue to deepen, and funds are being disbursed to improve police capacity and transform Mexico’s justice system. While these are positive steps and signs, the disturbing increase in homicides in Mexico during 2016 should raise concerns. It may be too early to predict a long-term rise in violence, but it also may be a warning sign that existing measures are not enough to reduce the violence and manage the risks associated with organized crime. It may be time to reexamine the strategy itself to determine if the dialogue, collaboration, and funding are directed in the right way.

If Mexico and the United States were to continue dialogue and funding without assessing the success of the strategy in objective terms — such as less violence and homicides, increased public trust and collaboration with the state, reduced numbers of at-risk youth, and the successful transformation of criminally active youth into positive contributors to society — then they risk failing to take advantage of good relations to define a more successful approach to security. Hopefully, this kind of reflection will help inform the decisions taken by the Trump administration when it inherits what has been a historic partnership between neighbors.

It is not unusual for a new administration to take time to take stock of the complex, multilayered relationship between the United States and Mexico. Both the Obama and Peña Nieto administrations did so, and made adjustments to the relationship within the framework of collaboration. So it will not be a surprise if the Trump administration takes some time to evaluate the relationship and its priorities with Mexico. The fundamental question it will have to answer is whether to continue the path of collaboration or pursue a more narrowly security-focused and unilateralist policy. Given the complex, serious issues on the security agenda and the strong track record of existing collaborative approaches, working together to solve mutual concerns is the preferred option.

An earlier Spanish-language version of this article will appear in the “Atlas de la Seguridad y la Defensa de México 2016,” Instituto Belisario Dominguez, Senado de la Repúbilca, México, Colectivo de Análisis de la Seguridad con Democracia. The author wishes to thank Ximena Rodriguez, the Mexico Institute’s research intern specializing in security cooperation, for her excellent research assistance throughout this project.

* * *

Eric L. Olson is the associate director of the Latin American Program and senior advisor on security to the Mexico Institute at the Wilson Center.

Cover photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons