Winter 2021

Back and Forth

– Stephanie Leutert

The Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) were devised in secret. The harsh spotlight on U.S. immigration policy makes them hard to roll back.

On January 29, 2019, Carlos Gómez Perdomo, a 55-year-old Honduran man exited the United States’ El Chapparal port of entry and walked alone toward Tijuana, Mexico. He stared mostly at the ground just ahead of his feet as he walked, carrying a file of papers in one hand and a faded blue backpack in the other.

Carlos wasn’t any ordinary border crosser. He was the first person of thousands who have been sent back to wait in Mexico under the United States’ new program for asylum seekers: the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP).

The new asylum program for the U.S.-Mexico border was agreed upon several months earlier at a secret meeting in a Houston hotel in November 2018 between U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, then-Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Kirstjen Nielsen, and incoming-Mexican Foreign Affairs Secretary Marcelo Ebrard.

The agreement was born of desperation. U.S. officials sought to stop asylum-seeking Central American families arriving in caravans at the southern U.S. border—a surge that led to increasing apprehension numbers and intense media coverage. President Donald Trump demanded a solution, especially since his administration’s previous attempts to stop asylum seekers were blocked in federal court, or reversed amid public outcry, or simply failed to deter them.

At the secret meeting in Houston, U.S. officials offered a new plan to their Mexican counterparts. Nielsen and Pompeo proposed sending asylum seekers back to Mexico to wait as their U.S. asylum cases were adjudicated. Asylum seekers would no longer live in U.S. cities, send their children to U.S. schools, or gain work in the United States. Instead, they would live in Mexican cities, cut off from the country processing their asylum claims.

Ebrard agreed to the rough outline of what became MPP. Mexico would accept the returned asylum seekers and promised to provide them with “humanitarian care and assistance, food and housing, work permits, and education.” Officials from both countries hashed out the details over subsequent weeks. The result was an asylum program that has fundamentally altered regional migration patterns, border dynamics, and tens of thousands of asylum seekers’ lives.

The initiative that started secretly in the Houston hotel has settled into a new status quo at the U.S.-Mexico border. And despite their stated intention to end MPP, the incoming administration will find it difficult to unwind. Starting on their first day in office, Joe Biden and his team will have to delicately balance how to roll back a program of this scope and complexity without triggering a new surge of asylum seekers.

A Speedy Implementation

Since January 2019, officials of the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) have sent more than 68,000 asylum seekers to Mexico as part of MPP.

When Secretary Nielsen began MPP’s implementation on December 20, 2018, she announced that DHS was relying on Section 235(b)(2)(C) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, which states that certain individuals can be returned to Mexico or Canada pending removal proceedings.

This provision had never previously been enforced, but U.S. officials argued that it allowed them to process asylum seekers in the United States and send them to Mexico with a “Notice to Appear” for their first U.S. court hearing.

In late January 2019, MPP was operational. DHS published implementation guidelines on January 28, and began a San Diego pilot program the next day. By March, MPP was established in Calexico and El Paso, expanding quickly to Brownsville and Nuevo Laredo in July.

CBP announced that MPP was fully operational along the entire border in September 2019, and later added two additional cities to the program: Eagle Pass (October) and Nogales (January 2020). It took a bit more than one year from proposal to full implementation.

Not all asylum seekers are subject to MPP. CBP only enrolls adults and families from Brazil and Spanish-speaking countries in Latin America—except Mexico—who enter the U.S. without appropriate migratory documents. Unaccompanied minors are not placed into the program, and CBP exempts asylum seekers with “known physical/mental health issues.”

The tens of thousands of asylum seekers in the program fit no single demographic profile. They include families with infants, young adults, and elderly people. Most of the asylum seekers are from Central America, but there is a varied nationality breakdown. As of October 2020, most MPP enrollees were from Honduras (34 percent), followed by Guatemala (23 percent), Cuba (15 percent), and El Salvador (12 percent). The remaining 16 percent are from other countries across the Western Hemisphere.

The initiative that started secretly in the Houston hotel has settled into a new status quo at the U.S.-Mexico border.

Asylum seekers in MPP remain in Mexico and only set foot in the United States for their scheduled court hearings. Program enrollees show up at their pre-determined port of entry on those dates for transport to U.S. immigration courts. In El Paso and San Diego, asylum seekers are shuttled to established immigration courts. CBP constructed tent courts alongside the ports of entry in Brownsville and Nuevo Laredo, so asylum seekers may walk directly into the facilities. After the court hearings, all MPP enrollees are sent back to Mexico.

Once placed in MPP, asylum seekers rarely leave the program. Those who fear targeted persecution in Mexico can request a non-refoulement interview with CBP officers who rarely grant exemptions. From January 2019 through October 15, 2019, U.S. asylum officers granted positive determinations for only 13 percent of MPP non-refoulement interviews.

Poverty, Homelessness, and Violence

As they are sent back to Mexico, MPP asylum seekers often experience shock and confusion. They made it to U.S. territory and requested asylum, yet they were detained, processed, and ended up back in Mexico. Their only link to the nation where they claimed asylum is a pack of documents with their first court date. A sheet of paper, written in English, contains the names and phone numbers of U.S. legal service providers.

Once back in Mexico, MPP enrollees walk to a National Migration Institute (Instituto Nacional de Migración, INM) office, where they receive “Visitor for Humanitarian Reasons” (Visitante Razones Humanitarias) documents. This status allows them to remain in Mexican territory and ensures that they will not be deported back to their countries of origin.

These documents do not permit any remunerated work, however. So asylum seekers must also receive a Unique Population Registry Code (Clave Única de Registro de Población, CURP)—the equivalent of a U.S. social security number—to work legally.

INM did not provided temporary CURPs to all asylum seekers in MPP, particularly as it was initially rolled out. From January 2019 through February 6, 2020, for instance, INM issued 3,438 temporary CURPS in Tijuana. Yet CBP sent around 7,400 asylum seekers to the city in that same period.

Asylum seekers are on their own as they walk out of INM offices with their documents. Their first challenge is finding a place to live. MPP enrollees are sent to border cities with at least one migrant shelter. Yet that often is no solution. These shelters are not always located near the border, or may not allow visitors to stay for more than a few days. They also quickly reach capacity. Though Mexican federal officials did construct MPP-specific shelters in Ciudad Juárez and Tijuana by the end of 2019, asylum seekers in these cities and along other parts of the border continue to experience unstable living conditions.

Asylum seekers have at times banded together to address their precarious housing situations. In Matamoros, across the border from Brownsville, asylum seekers set up a tent encampment outside the port of entry. By November 2019, more than 3,000 asylum seekers were living in the tent camp, which had spilled onto the Rio Grande’s banks. One year later, in November 2020, approximately 700 asylum seekers continued to live in the camp.

Legal support for MPP enrollees is also elusive. To have a chance at gaining relief, asylum seekers must find a U.S. lawyer to help them navigate the system. Some volunteer legal service providers have offered assistance in specific Mexican border cities, but most asylum seekers never obtain their own lawyers. According to Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) data, which documents MPP cases, only 14 percent of ongoing asylum cases in MPP have legal representation.

Asylum seekers are on their own as they walk out of INM offices with their documents. Their first challenge is finding a place to live.

Yet the biggest challenge facing those enrolled in MPP is rampant crime and violence in Mexican border cities. The program ensures that they are sent back to some of the most dangerous areas in Mexico.

The U.S. State Department lists the state of Tamaulipas, where Matamoros and Nuevo Laredo are located, as a “Do Not Travel” destination due to crime and kidnapping. It also lists the states of Coahuila, Chihuahua, and Sonora—which includes the cities of Piedras Negras, Ciudad Juárez, and Nogales—in its “Reconsider Travel” category. From January 2019 through May 13, 2020, Human Rights First documented 1,314 publicly reported crimes against asylum seekers in Mexican border cities.

Violence levels are particularly egregious in Nuevo Laredo. Since July 2020, the Northeast Cartel (Cartel del Noreste) has systematically kidnapped MPP participants. Cartel lookouts wait outside the city’s INM office, alerting kidnappers as asylum seekers walk toward the city’s shelters. These lookouts are also active at Nuevo Laredo’s bus stations, striking as MPP enrollees attempt to leave the city or return for their court hearings. In October 2019, Doctors Without Borders noted that 33 of the 44 MPP asylum seekers that they treated in Nuevo Laredo had been recently kidnapped.

Intended Effects – Even in a Pandemic

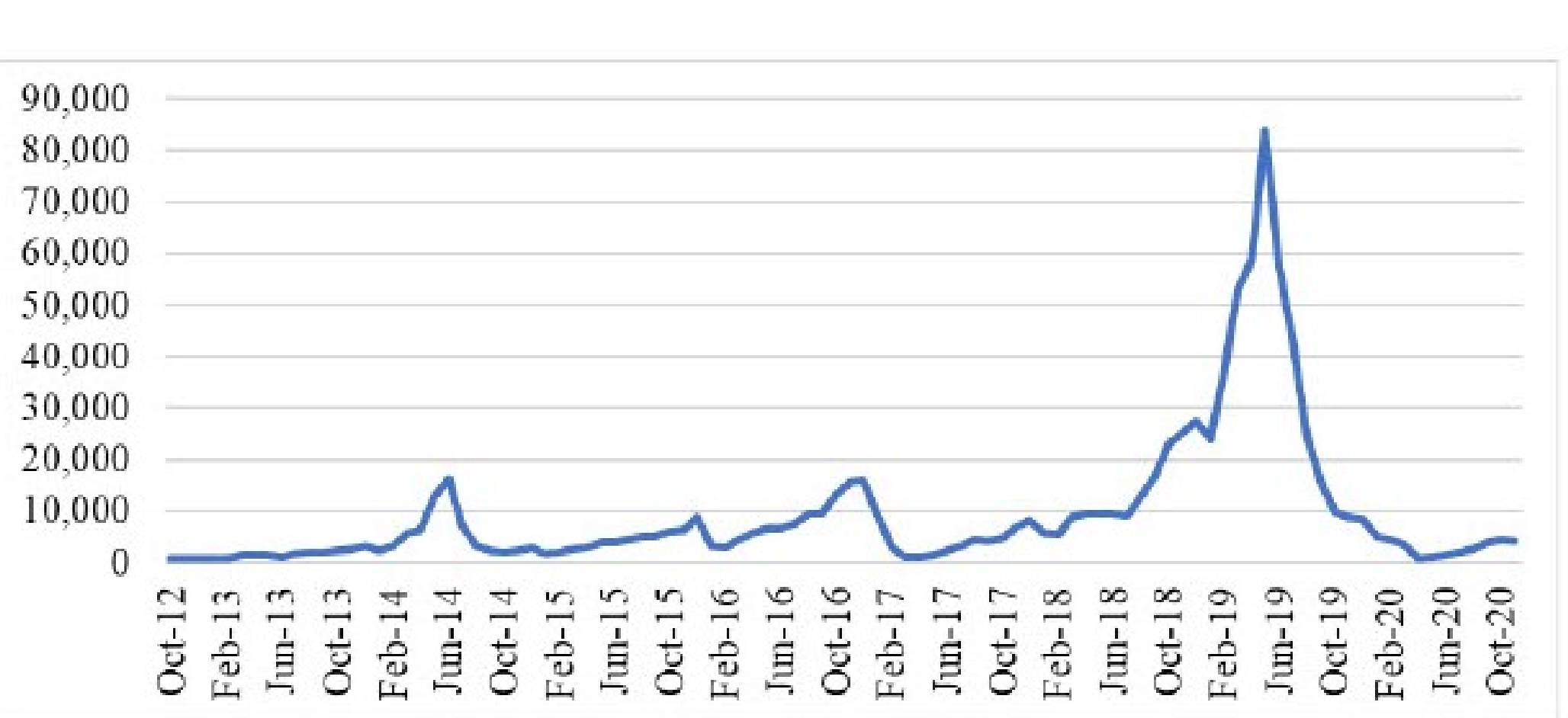

DHS officials who designed and implemented MPP believe the program achieved its intended effect: reducing the number of people making asylum claims at the border. Family apprehensions plummeted as CBP operationalized the program along the entire border. In May 2019, the Border Patrol apprehended 84,486 parents with minor children, but by October 2019, they only apprehended 9,721 family members—an 88 percent decline.

Increased Mexican immigration enforcement operations also contributed to these declining numbers. A May 2019 tweet by President Trump threatened five percent tariffs on Mexican goods if that country did not stop Central Americans from reaching the U.S. border. Negotiations led Mexico to deployed its National Guard to support INM’s enforcement efforts, which increased the number of apprehensions and deportations.

A deeper look into the numbers confirms that it is not merely enforcement efforts that have an impact. Under U.S. pressure, INM deported roughly 3,000 more Central American family members in June 2019 than it had the previous month. By comparison, the number of CBP family apprehensions dropped by 27,100 people in the same time frame. While Mexico’s operations reduced the number of asylum seekers arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border, MPP was already transforming migration dynamics.

Even a global pandemic has not altered the program’s trajectory. While MPP has changed under COVID-19, it still continues to operate. The Department of Justice (DOJ) and DHS halted MPP court hearings in March 2020. At present, they have not restarted. In July 2020, DOJ and DHS published their criteria for restarting hearings, which includes the requirement that all U.S. and Mexican border states reach moderate levels for COVID-19.

Despite the closed courts, CBP has continued to enroll new asylum seekers into MPP, albeit at a lower rate than before. From April 2020 through October 2020, CBP added 3,546 people to the program, with two thirds of these new entrants being enrolled in El Paso. This is a stark difference from other parts of the border. For example, since April 2020, CBP officers in San Diego and Calexico have placed far fewer people—only 240—into MPP.

In addition, MPP complements CBP’s other COVID-19 related immigration policies. On March 21, 2020, CBP activated the use of Title 42 expulsions for apprehended individuals along the U.S.-Mexico border due to the pandemic. This authorizes CBP officers to send apprehended individuals—including asylum seekers—immediately back to Mexico.

Even a global pandemic has not altered the program’s trajectory. While MPP has changed under COVID-19, it still continues to operate.

Since Mexico currently only accepts expulsions of Mexicans and Central Americans, CBP generally flies individuals of other nationalities back to their country of origin—or puts them into MPP if they are asylum seekers.

Dual use of Title 42 expulsions and MPP in the COVID-19 environment has altered new MPP entrants’ nationalities. From April 2020 to October 2020, 59 percent of new entrants in MPP were from Cuba. Another 25 percent were from Ecuador, 6 percent were from Nicaragua, and 3 percent were from Brazil. Fewer than 3 percent of new MPP entrants were from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador.

The Challenge of Unwinding

After two years, MPP may soon reach its end. Throughout the 2020 campaign, President-elect Joe Biden and his team repeatedly promised to roll back the Trump administration’s asylum policies, starting with MPP. But unwinding the program will not be easy. It will require an answer to four essential questions.

The first question concerns scope. Since January 2019, CBP placed 68,000 people in MPP, but there are only 22,777 cases pending in MPP border courts. Will a roll-back target only asylum seekers with pending cases, or will it encompass all individuals enrolled in MPP? (The latter scope would deem that the program did not provide meaningful access to the U.S. asylum system.) And would asylum seekers in MPP who entered the U. S. undetected between ports of entry (with cases pending or closed) be included?

Another challenge is contacting asylum seekers within the target population to alert them of policy changes. This will not be an easy task. The U.S. immigration system communicates with asylum seekers through the postal service, and asylum seekers in MPP do not have valid addresses for mail to reach them.

CBP officials often wrote a standard Mexican address on initial MPP forms. For example, CBP officials used the Casa Nazareth shelter’s address in Nuevo Laredo for many of the 13,238 asylum seekers sent to that city and to Piedras Negras. Yet, as of October 2020, only a handful of MPP asylum seekers were actually staying in that shelter, and most were living in other Mexican cities.

A third issue will be processing the target population into the United States. This step may appear simple, since asylum seekers in MPP can be paroled into U.S. territory. However, security issues and COVID-19 create additional processing considerations. Asylum seekers returning to their original port of entry may face dangerous conditions and require processing location flexibility to stay safe. Additionally, COVID-19 concerns will require a strategy for orderly and socially-distanced processing, including testing and a potential quarantine.

Throughout the 2020 campaign, President-elect Joe Biden repeatedly promised to roll back Trump asylum policies. But unwinding the MPP will not be easy.

These tasks must be completed in close coordination with civil society groups in U.S. border cities. These organizations can provide valuable assistance throughout the entire process, including providing quarantine spaces, and assistance with immediate housing, food, and basic hygienic needs, as well as travel arrangements. Legal service providers can reinforce information on how asylum seekers can transfer their cases to different immigration courts and obtain legal services in their new hometowns.

The last question—and perhaps the hardest to answer—is how to unwind MPP without generating a new immigration surge. The program reduced the numbers of arriving asylum seekers at the border. Will its removal cause the opposite effect? It will likely depend on how many additional immigration and border programs remain in place.

CBP has introduced additional asylum policies, including Title 42 expulsions, since MPP’s implementation. A blanket rollback of all programs would recreate a pre-MPP state—and put conditions in place for a surge in asylum-seeking families. But eliminating MPP, while leaving all other policies intact, would barely change the status quo. Title 42 expulsions would continue to block most asylum seekers from reaching the U.S. system—and could likely be adjusted to incorporate all persons who arrive to make a claim.

Removing MPP alone will not create a sustainable asylum policy. Ongoing lawsuits may deem Title 42 illegal. Additionally, this measure has also led to an increase in adult apprehensions, since the rapid expulsions it enables have meant that apprehended individuals are not criminally prosecuted for irregular entry into the United States.

Yet, more importantly, the Biden administration campaigned on promises of restoring the U.S. asylum system. Sustainably and comprehensively addressing a potential surge in asylum-seeking families requires additional measures to address regional migration. The list of necessary steps is long, and will likely include substantial foreign assistance to areas with high-rates of outward migration, in-country or regional refugee processing, targeted work visas, and updates to the U.S. asylum system.

Evolution and Continuity

It has been two years since U.S. and Mexican officials met secretly in a Houston hotel. The policy landscape at the border shared by these two nations no longer looks the same. There are more asylum programs, but less access to the U.S. asylum system. Title 42 expulsions have halted all processing of claims along the border and transformed migration dynamics. As a result, individuals crossing the border today are more likely to attempt to evade Border Patrol agents than seek them out to ask for asylum.

Yet until new policy is adopted, CBP will continue to place hundreds of asylum seekers into MPP every month. And like the very first Honduran man who emerged from the U.S. port of entry and walked into Tijuana, these asylum seekers head into Mexican border cities without housing, legal advice, or guaranteed security. As MPP enrollees, they continue to carry their belongings and court papers into Mexico—and leave behind their asylum cases in the United States.

Stephanie Leutert is the Director of the Central America and Mexico Policy Initiative at the Robert Strauss Center for International Security and Law at the University of Texas at Austin.

Cover Photograph: U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers listen to President Donald J. Trump during his visit to an overlook along the Rio Grande near the U.S. Border Patrol McAllen Station in McAllen, Texas on January 10, 2019. (Official White House Photo by Shealah Craighead)