Fall 2007

Platonic Thoughts

– Brendan Boyle

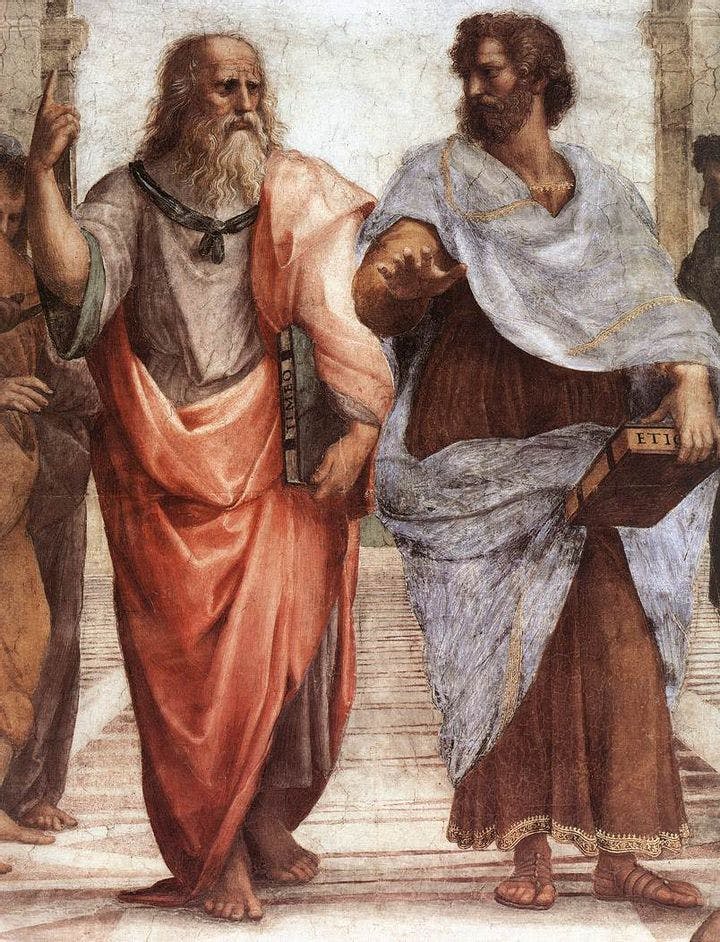

The enduring beauty of Plato's Republic.

Ralph Waldo Emerson remarked admiringly of Plato, "An Englishman reads and says, ‘how English!’ a German—‘how Teutonic!’ an Italian—‘how Roman and how Greek!’ . . . Plato seems, to a reader in New England, an American genius. His broad humanity transcends all sectional lines." Simon Blackburn thinks Emerson was essentially, but not entirely, right, and in this volume of the Atlantic Monthly Press’s Books That Changed the World series, he traces the vexing appeal of Plato’s mighty Republic.

Plato (c. 428 BC–c. 347 BC) wrote the Republic in Athens around 375 BC. By then he had come to loathe the city, which he regarded as little more than an ignorant rabble ruled by corrupt demagogues. The Republic seeks to demonstrate what a truly just city looks like and, in the process, to expose Athens—which had executed Plato’s teacher, Socrates, some two decades earlier—as a sham.

The Republic’s central claim, spelled out in a dialogue between Socrates and several interlocutors, is that justice and happiness stand and fall together. Not because good consequences—a fine reputation, say—follow from being just, but because justice itself is so great that nothing gained by injustice could be greater. By "justice," Plato means more than honoring agreements or obeying the law. A just person does these things, but only because his soul is rightly ordered: Reason rules over desire. The same goes for a just city. The wise rule, the rest obey, and justice is the result.

Blackburn, a philosopher at the University of Cambridge, isn't buying it. What about Machiavellians who coolly check their passions so that they can practice even greater injustice—and who seem happy to boot? He has in mind those enfants terribles, American neoconservatives, but his more intriguing example is from the Peloponnesian War. In 416 BC, Athens sent 10,000 men against the tiny island of Melos, which fielded scarcely 500. The Melians asked Athens’s envoys to respect their neutrality, and got this response before they were slaughtered: "The strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must." The Athenians, Blackburn says, showed precisely the sort of dispassionate self-governance that Plato associates with justice. Yet they acted unjustly, and were none the worse for it.

Blackburn’s criticisms don’t end there. Plato’s ideal rulers are philosopher-kings who make Blackburn shudder—probably because he knows what despots ruling in the name of wisdom have done. "In so far as Plato has a legacy in politics," he writes, "it includes theocracy . . . , militarism, nationalism, hierarchy, illiberalism, totalitarianism, and the complete disdain of the economic structures of society."

If its argument fails and its politics frighten, why, in the words of Plato scholar M. F. Burnyeat, is there "always someone somewhere . . . reading the Republic"? Perhaps for the same reason that someone is always looking at the sun. Both are enormous and abiding, absolutely of this world yet alien to it. And both are things of beauty.

Many remember the Republic’s haunting metaphor of the cave, to which Blackburn devotes several chapters. But for my money, the Republic’s beauty arrives more casually. When, for example, Socrates senses a friend growing weary during the discussion, he urges, "We must station ourselves like hunters surrounding a wood and concentrate our minds, so that our quarry, justice, does not vanish into obscurity."

Blackburn calls this "tedious dramatic buildup." Others call it poetry. Blackburn is a philosopher whom John McCain might like— straight-talkin’, no-nonsense. This sensibility suits tartly argued earlier books by Blackburn such as Truth: A Guide (2005) and Being Good: A Short Introduction to Ethics (2001), but he can’t quite figure out what to make of the Republic. Still, he is awed by the purity of Plato’s demand that we change our lives. In the end, he can’t help but admire what Virginia Woolf called "the love of truth which draw[s] Socrates and us in his wake to the summit where, if we too may stand for a moment, it is to enjoy the greatest felicity of which we are capable."

* * *

Reviewed: "Plato's Republic: A Biography" by Simon Blackburn, Atlantic Monthly Press, 2007.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons