Fall 2008

Bulletins from Immortality

– Stephanie E. Schlaifer

Reviewer Stephanie E. Schlaifer looks at Brenda Wineapple's account of the quarter-century relationship between poet Emily Dickinson and political activist Thomas Wentworth Higginson.

It was Emily Dickinson who initiated the correspondence, in 1862, sending Thomas Wentworth Higginson four poems and a brief query, “Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?” In White Heat, Brenda Wineapple explores the quarter-century relationship of Dickinson, the prolific and famously eccentric poet, and Higginson, a minister, political activist, and gentleman-of-all-trades. The book, Wineapple declares, is neither biography nor literary criticism, but an effort “to throw a small, considered beam onto the lifework of these two unusual, seemingly incompatible friends.”

Wineapple illuminates the oft-neglected life of Higginson (1823–1911), who served during the Civil War as a colonel in the first Union regiment composed entirely of former slaves, was an avid contributor to The Atlantic Monthly (which published his article of advice to writers, “Letter to a Young Contributor,” prompting Dickinson’s first s poems. But a greater portion of the book is devoted to Dickinson (1830–86), known as much for her reclusive behavior and her penchant for all-white garb as for her pithy verse with its signature long dashes and hymnal rhyme and meter. About her, there will likely always be more questions than answers.

Though they both lived in New England, the pair met only twice during their 25-year correspondence. The first meeting, in 1870, evidently left Higginson so drained that he confessed to his disapproving wife, “I am glad not to live near her.” They had been discussing poetry when Dickinson declared, “If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. . . . Is there any other way.”

Dickinson pressed Higginson many times to visit her again after a second meeting three years later, but he acquiesced only at her passing, when he attended her funeral. He once wrote to her, “I have the greatest desire to see you, always feeling that if I could once take you by the hand I might be something to you; but till then you only enshroud yourself in this fiery mist & I cannot reach you, but only rejoice in the rare sparkles of light.”

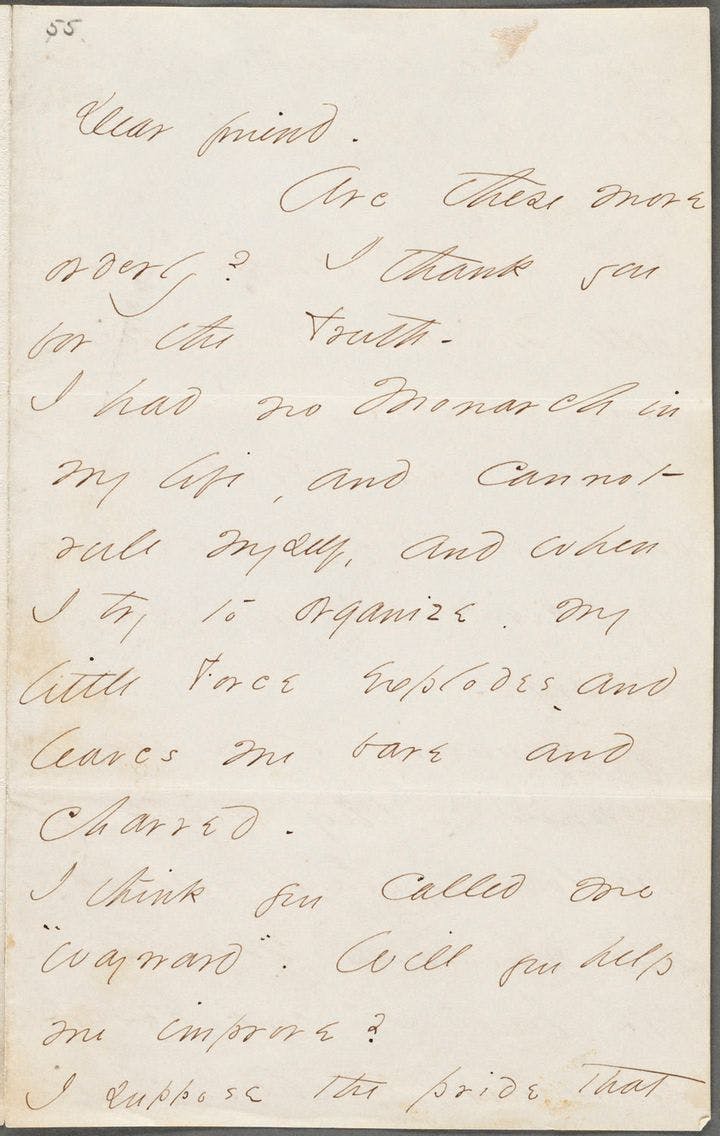

Without explanation, Wineapple gives us only brief excerpts from the two’s epistolary exchange, and this is a disappointment. Most of Higginson’s s vive. (What is most remarkable about them is how similar the prose is to her poems—she seems not to have been able to keep from expressing herself in meter and rhyme.) Still, through the bits of correspondence we are afforded, Wineapple shows us a central conceit of this complicated relationship: Dickinson often presented herself as pupil to Higginson’s master or “preceptor”—a flirtatious ruse they both seemed tacitly to acknowledge and enjoy. If Dickinson habitually ignored Higginson’s suggestions for her verse, he certainly influenced her. Wineapple includes a number of poems clearly prompted by essays, stories, and poems Higginson was publishing.

Dickinson’s impassioned exchanges were not restricted to Higginson, and the book is most engaging when exploring the handful of other close relationships Dickinson maintained—with her sister Lavinia (Vinnie), the exuberant writer Helen Hunt Jackson, and her sister-in-law Sue, the only person with whom Dickinson shared more of her poems than Higginson. Each of her carefully chosen companions served a distinct function in her life and after.

Dickinson instructed Vinnie to burn her papers upon her death, which she did. Emily evidently had said nothing about her poems, which were kept separately from the papers. Upon discovering these, Vinnie, Higginson, and the devil-may-care socialite and writer Mabel Loomis Todd set about publishing Dickinson’s poems at last. It appears that Todd was responsible for the transcription of Dickinson’s poems and the unforgivable liberties taken in editing them.

Todd is also remembered for her not-so-clandestine affair with Austin Dickinson, Emily’s brother. Most of the book’s true heat derives from the account of this affair—a juicy respite from White Heat’s more serious literary thrust—one I admit I enjoyed.

* * *

Stephanie E. Schlaifer is a poet and editor based in St. Louis. Her work has appeared in Fence, Delmar, elevenbulls, and elsewhere.

Reviewed: White Heat: The Friendship of Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson by Brenda Wineapple, Knopf, 416 pp,

Photo courtesy of the Boston Public Library