Fall 2008

Fuller's Earth

– Edward Tenner

Edward Tenner reviews a biography of Buckminster Fuller.

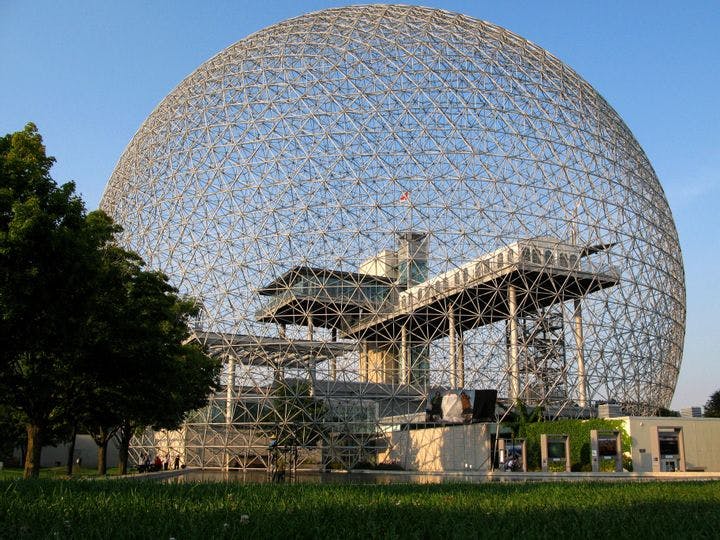

When he died in 1983, Buckminster Fuller was the world’s most beloved designer, a pioneer of bold new geometric concepts in transportation (the streamlined Dymaxion Car), housing (the geodesic dome, a lightweight hemisphere of connected polygons), and urbanism (a supersized dome proposed to cover central Manhattan), a best-selling author and mesmerizing speaker, and a prophet of environmental stewardship. Two years later, investigators named a newly discovered spherical carbon molecule, with a structure like the dome’s, the “Buckminsterfullerene” in his honor. The Nobel Prize in Chemistry they received for this work in 1996 helped create a new generation of Fuller admirers. But their prolific hero is hard to know.

Preppy nerd and buttoned-down bohemian, green guru and globe-trotting jet fuel consumer, a college expellee who relished honorary degrees, Buckminster Fuller

(b. 1895) proclaimed a new cosmos of structural lightness and left a personal archive of 45 tons about it. It is indicative of Fuller’s paradoxes that the cocurator of the Whitney Museum’s exhibition of his work that closed earlier this fall, Harvard Graduate School of Design professor K. Michael Hays, should open and close his introduction to this catalog by underscoring that Fuller was not an architect.

So what was he, then? Hays shows how Fuller’s “lightful” plans of the 1920s and ’30s for new housing suspended from vertical masts were part of a Modernist reaction against the values of weight and solidity that had prevailed from antiquity to World War I. Fuller’s designs reflected the propagandistic architecture of the Soviet avant-garde before Socialist Realism’s triumph, as well as the expansive vision of the Swiss master of self-invention and self-promotion, Le Corbusier. What distinguished Fuller from these contemporaries, Hays says, were a lack of “reflexivity” (conscious references in design to architecture’s heritage), de-emphasis of stability in favor of dynamic relationships, and a denial that nature, humanity, and technology are distinct entities. While a massive challenge to the uninitiated, Hays’s chapter clarifies Fuller’s complex symbiosis with Establishment architects and critics.

Buckminster Fuller was a preppy nerd and buttoned-down bohemian, green guru and globe-trotting jet fuel consumer; he proclaimed a new cosmos of structural lightness and left a personal archive of 45 tons about it.

An essay on Fuller as scientist-artist, by Whitney associate curator Dana Miller, is more illuminating about the man himself, showing how much of Fuller’s secret was his gift for friendship. This magnetism helped make Fuller exceptionally resilient, and a catalyst of colleagues’ work. The chairs he designed for an avant-garde Greenwich Village bar collapsed on opening night in 1929 and were replaced by benches built by a carpenter. But his renown among the tavern’s bohemian customers suffered not a bit; one patron, Isamu Noguchi, painted his studio silver following Fuller’s plans, and created a chrome-plated bronze portrait head of Fuller echoed 35 years later in Boris Artzybasheff’s illustration for a 1964 Time cover. Elizabeth Smith, a curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, brings the story of Fuller’s legacy in contemporary art up to date, seeing his influence in the work of artists such as Olafur Eliasson and Irit Batsry.

Antoine Picon, also of Harvard, makes the case for Fuller as a prophet of today’s digital utopianism, as a brilliant innovator in the visual presentation of data (especially his geodesic projection of the globe), and as a progenitor of general-systems approaches to resource management. But Picon also rightly observes that Fuller was “at heart a traditional humanist.” Megastructures such as the planned Manhattan dome, in Fuller’s view, were not opposed to human scale but a means of liberation from “the mechanical enslavement of the industrial era.”

The great attraction of this book is the 175 plates and the other illustrations, superbly reproduced, that show the many sides of Fuller: geometric visionary, practical designer, and super salesman. But Fuller’s contradictions remain unresolved, and some of his greatest predecessors and successors are absent from the book. For example, Walther Bauersfeld, developer of the Zeiss projection planetarium, patented a geodesic dome for it three decades before Fuller received his own dome patent in 1954. Hays reprints a 1928 photograph by László Moholy-Nagy of a Zeiss dome under construction, without citing Bauersfeld.

As chronological documentation and visual inspiration, Starting With the Universe will be an entry point for the study of this most unusual man. But the successors of the publics that responded so warmly to Fuller’s many sides during his lifetime, from Pentagon technocrats to Haight-Ashbury hippies, will have to wait for a work that sets the real man in his own time.

* * *

Edward Tenner, a contributing editor of The Wilson Quarterly, is the author of Why Things Bite Back: Technology and the Revenge of Unintended Consequences and Our Own Devices: How Technology Remakes Humanity.

Reviewed: Buckminster Fuller: Starting with the Universe edited by K. Michael Hays and Dana Miller, Yale University Press, 258 pp, 2008.

Photo courtesy of Flickr/Paula Soler-Moya