Fall 2008

Hollywood's Crucifixion

– Aaron Mesh

Aaron Mesh on Hollywood's controversial attempts to portray the last days of Jesus Christ on film.

When Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ was released in 1988, it met with thunderous outrage. Paul Schrader, the film’s screenwriter, recalls walking into Scorsese’s office to find the director bemoaning the furor. “I said, ‘Marty, we wanted to make a controversial film,’” Schrader recounts. “‘We have now made a controversial film.’” Scorsese replied, “I know, I know, but I didn’t think it would be this controversial.”

Hollywood Under Siege is Thomas R. Lindlof’s detailed account of that controversy and how it dug the trenches for two decades of social battles between Christian conservatives and left-wing artists. Lindlof, a journalism professor at the University of Kentucky, observes that Last Temptation was released before the phrase “culture wars” had appeared much in print. The movie helped to make it part of the American vocabulary.

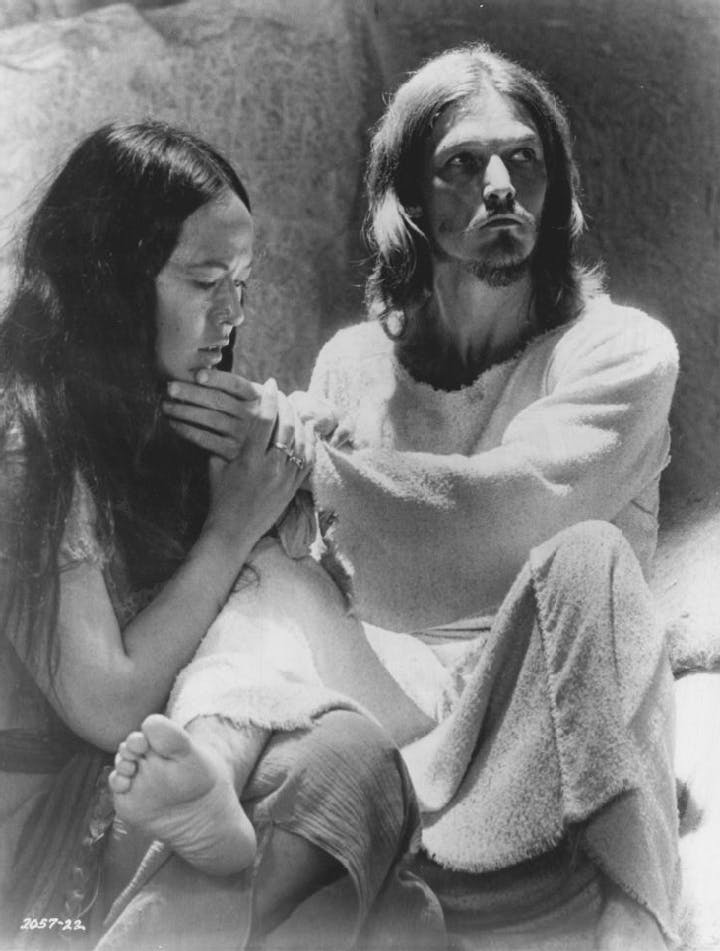

In a sense, then, the story of how Last Temptation came to be made is from a more innocent time. A prestigious director could make a movie featuring Jesus Christ fantasizing about having sex with Mary Magdalene, and a powerful studio, Universal Pictures, would green-light the project. Both parties thought nobody would mind—or that they would mind just enough to make the film notorious, and profitable.

The book plays as a bleak comedy of naiveté lost. During the summer of 1988, Last Temptation “survived the denunciations of preachers and politicians, mountains of mail delivered to Universal City, death threats to executives, demonstrations attended by thousands of citizens, and assaults on theaters and moviegoers.” As both Universal Pictures and Christian groups such as Focus on the Family congratulated themselves for standing firm, they created a template for unending hostility: Evangelicals believe that Hollywood is constantly plotting new blasphemies, while studios fear that any treatment of religious content will draw an outcry.

Lindlof documents absurdities on both sides. Conservative newsletters, for example, had long circulated rumors of a movie in the works that would portray Jesus as a homosexual, and many Christians’ fears about Last Temptation were intensified when they confused the two projects. Evangelical activists first threatened pickets when Last Temptation wasn’t screened for them—and when Universal belatedly arranged a showing, they refused to attend. The most outrageous preachers relied on anti-Semitism—blaming Jewish studio heads for attacking Jesus—even though the movie was directed by a Roman Catholic, written by a Dutch Calvinist, and based on a novel by the Greek Orthodox writer Nikos Kazantzakis.

But Hollywood made its blunders, too. Scorsese, a lapsed Catholic whose faith was informed by existential doubt and struggle, failed to anticipate how violently evangelicals would react to a movie that was, as one executive said, basically It’s a Wonderful Life with Jesus as George Bailey, conjuring an alternative world in which he sired children with several women instead of dying on the cross. Studio bosses were equally clueless, even when they thought they were taking pains to be sensitive: Young Paramount Pictures executive Jeffrey Katzenberg asked Scorsese to “pay special attention to not make Jesus unlikable” in a scene in which he rejects his mother.

Lindlof is better on the inner workings of studio politics and crisis management than he is on evangelicalism. His case that fundamentalist leaders seized on Last Temptation to rebound from the sex scandals of Jimmy Swaggart and Jim Bakker is purely circumstantial, and he never displays a firm understanding of the average protester’s mindset. But Hollywood Under Siege correctly identifies the movie’s release as a cultural watershed. It made $8 million at the box office and broke even, but studios would never again assume that evangelicals were an extremist fringe, and grew shy of even mild religious material.

Nearly two decades after Scorsese’s film, Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ—“a reverse image of Last Temptation in almost every respect,” Lindlof writes—raked in $370 million and proved that fundamentalists would embrace a cinematic Jesus, so long as he was portrayed as a sacrificial lamb. It didn’t even matter if that sacrifice was reenacted with ceaseless sadism. Hollywood had learned its lesson: If you can’t beat ’em, join ’em in beating him.

* * *

Aaron Mesh is the chief movie critic and a culture editor for Willamette Week, an alternative weekly in Portland, Oregon.

Reviewed: Hollywood Under Siege: Martin Scorsese, the Religious RIght, and the Culture Wars by Thomas R. Lindlof, University Press of Kentucky, 394 pp, 2008.

Photo courtesy of Wikipedia