Fall 2012

Looking at Tocqueville's blind spots

– The Wilson Quarterly

"Tocqueville was deeply worried by American individualism, equating it with corrosive selfishness."

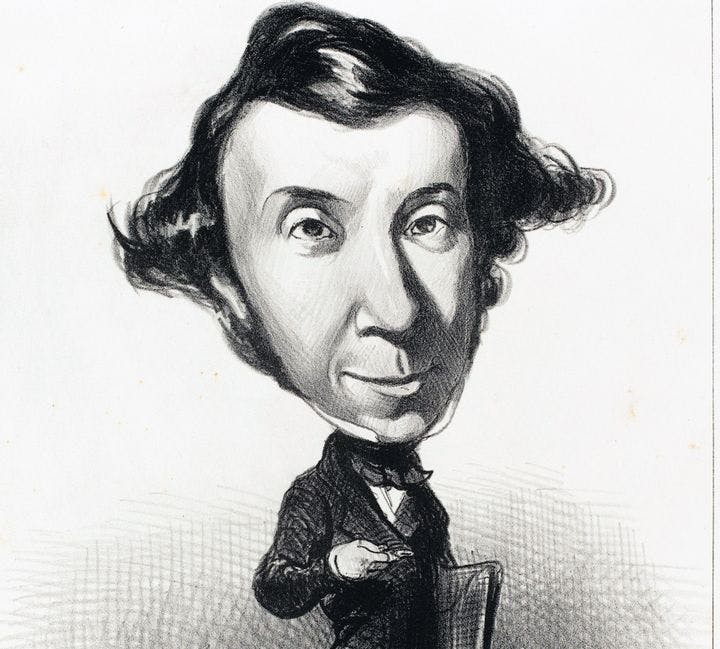

Alexis de Tocqueville literally wrote the book on the Unites States. Democracy in America (1835–1840), informed by his wide-ranging nine-month visit to the country, is generally recognized as one of the classic studies of American political culture.

But Tocqueville was only human, and Democracy in America is still just a book. For all its insight, writes the late political scientist James Q. Wilson, the French nobleman’s magnum opus “left a bit to be desired.”

Tocqueville believed that Americans would come to value equality over liberty. Reasoning that liberty appears immediately valuable only to dissidents, he concluded that equality, which can be enjoyed by all immediately, would lure the general public. But he was wrong, Wilson writes, observing that “we accept economic inequality here to a much greater degree than it is accepted elsewhere.” He notes that many Americans oppose equality-driven measures such as the inheritance tax and affirmative action quotas. Freedom, rather, is “the central organizing story of American life.” U.S. soldiers returning from Iraq, for example, often said they were defending freedom—even though that’s not the reason U.S. leaders gave for the Iraq war.

Tocqueville was deeply worried by American individualism, equating it with corrosive selfishness. But for Americans, Wilson argues, individualism has more to do with being “masters of our own souls.” A healthy skepticism of majority opinion hasn’t made us indifferent to others. Americans value local governance and excel in collective enterprises; compared to the people of other countries, Americans are much more likely to join civic groups and other voluntary organizations.

If you really want an acute 18th-century perspective on how the United States would work, Wilson argues, you should look to the men who wrote the U.S. Constitution. While Tocqueville feared that democracy would lead to a tyranny of the majority, the Founding Fathers predicted the emergence of factions. Tocqueville hoped Americans’ customs and mores would preserve liberty; the Founders saw the need to design new means of doing so, notably the separation of powers. And while the aristocratic Tocqueville dismissed commerce as vulgar, Alexander Hamilton and others prevailed over their opponents and shaped a frankly commercial republic, paving the way for American prosperity.

Tocqueville did see one thing more clearly than the Founders. He argued that religion was needed to temper and broaden individuals’ understanding of what constituted their self-interest, and that Protestant traditions of self-government had a restraining influence on the formation of interest groups. The Founders, however, were largely silent on religion in writing the Constitution, recognizing that it would be impossible to encompass all the religious traditions that existed in America.

Acknowledging Tocqueville’s greatness, Wilson qualifies his criticism by explaining, “I want to put Tocqueville in context; I do not want him to be a cardboard hero of American thought with all of his arguments left unexamined.”

THE SOURCE: “Tocqueville and America” by James Q. Wilson. The Claremont Review of Books, Spring 2012.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons