Fall 2012

How the way we talk about Native Americans distorts our actual history

– The Wilson Quarterly

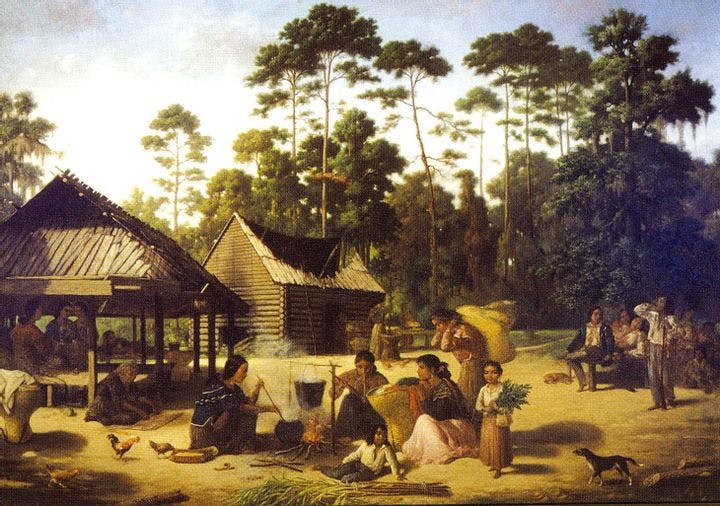

In earlier times, Native Americans often tended large farms. You wouldn’t know that from reading most scholars’ work.

Native Americans number in the millions today, and their colonial-era ancestors often tended large farms and lived in settlements across a broad swath of North America. But you wouldn’t know that from reading most contemporary scholars’ work, says James H. Merrell, a historian at Vassar College.

Merrell, who pioneered a new understanding of Native Americans in books such as The Indians’ New World: Catawbas and Their Neighbors From European Contact Through the Era of Removal (1989), argues that even many of the best-intentioned historians cling to a flawed vocabulary that distorts our view of history. Largely inherited from the colonial era, today’s terminology is an obstacle to accurately describing what is now known about early America.

Historians still commonly associate Native Americans with words related to hunting, such as “forest,” “wilderness,” and “wild,” apparently ignoring long-known evidence of Indian agriculture. A Virginia colonist wrote in 1650 of an “immense quantity of Indian fields cleared already to our hand, by the Natives.” An early New England writer admired “diverse acres being clear so that one may ride ahunting in most places of the land.” Colonial armies certainly knew about large-scale Indian agriculture: They seized 70,000 bushels of corn from Cherokee farmers during the Revolutionary War.

Nonetheless, when historians do refer to indigenous farming, they tend to minimize it. While they often say that Indians “grew vegetables” in “gardens,” the colonists are frequently described as having cultivated well-tended farms.

Merrell also takes issue with descriptions that give a sense of “a few scattered tribes” of Indians in parts of the country. As recently as 2006, one historian wrote that “everything west of the Alleghenies was bison” in early America. Modern maps often compound the problem, inaccurately depicting whole regions as being devoid of indigenous inhabitants, or including only a fraction of their Native American residents. Yet John Winthrop, the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, described the Narragansett Bay area of New England as “full of Indians.”

Careless scholarship distorts the present, too. A historian’s book from 2002 consigns Mohegans, Pequots, and Narragansets to the “many extinct eastern tribes,” when in reality they retain the status of federally recognized nations. Creeks and Seminoles are frequently killed off by historians, even though there are tens of thousands of them in southeastern states. Another historian mentions “Indian extinction” in his book published in 2007, despite the presence of scores of tribes in the United States today.

All this loose talk is a holdover from “the imperial project of relieving Indians of their sovereignty and their land,” Merrell argues. It was easier for colonists to justify pushing back some scattered Indian hunters than large populations of settled farmers.

“Surely at the dawn of a new millennium,” Merrell writes, “we can at least aspire to other ways of talking about early America.”

THE SOURCE: “Second Thoughts on Colonial Historians and American Indians” by James H. Merrell, in the William and Mary Quarterly, July 2012.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons