Fall 2011

For books, the term "bestseller" has no consistent meaning

– The Wilson Quarterly

A book’s “popularity can be understood as both proof and negation of its value.”

In 1895, a trade magazine published a list of books “in order of demand.” Since then, Publishers Weekly, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Amazon.com, and IndieBound (an association of independent booksellers), among others, have compiled their own bestseller lists. But while the term bestseller sounds authoritative, it has no consistent meaning. Each publisher gleans its numbers from different sources; the Times, for instance, relies on reports from a changing cast of 4,000 booksellers, IndieBound only on those from independent bookstores. “A writer with a carefully timed marketing blitz,” writes New Republic senior editor Ruth Franklin, can elbow onto a list for a day—long enough to claim permanent status as a best-selling author.

The lists’ meaning is inconsistent in another way: Over the years, works by Edith Wharton, Virginia Woolf, Ernest Hemingway, and other literary greats have ascended the lists, but so have Christian morality tales, Danielle Steel romances, and horror stories. Novelist Zane Grey lassoed top spots with his dime store westerns. Franklin surveyed the 1,150 top 10 fiction titles that have appeared on the Publishers Weekly list since its inception, hoping to learn what bestsellers do have in common. Her finding? Not much.

Her sampling of bestsellers reveals even some of the campiest to be what George Orwell, quoting G. K. Chesterton, called “good bad books,” enjoyable to read however much “one’s intellect simply refuses to take [them] seriously.” But if the majority of titles have been forgotten, Franklin writes, “it is the outliers—the one-hit wonders, the dynamos that suddenly shot to the top of the list while the mainstays languished in the lower digits—that remain most readable and relevant, both for the skill of their storytelling and for their surprising revelations about social mores.” Literary works enjoyed a heyday in the 1960s and ’70s, when graphic sexuality in novels such as Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer (1961) and Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint (1969) helped them attract readers.

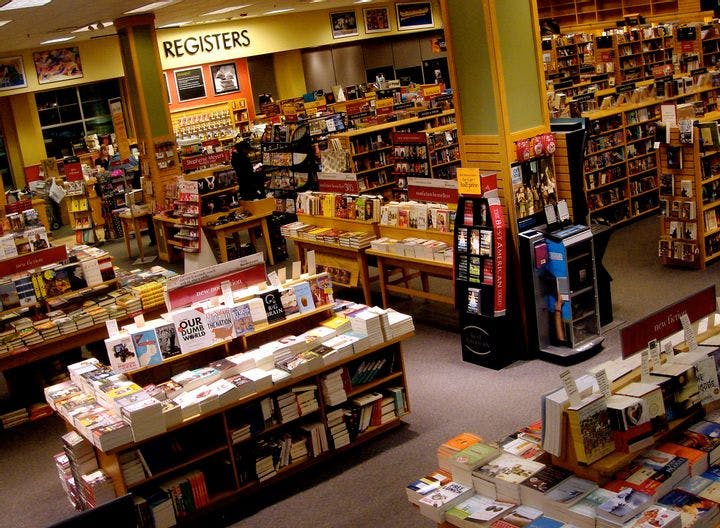

Think the bestseller you bought is a sure winner? Think again — the term has no consistent meaning.

With the rise of chain bookstores and huge publishing houses headed by executives who appreciate commercial over literary heft, bestseller lists have become homogenized. Indeed, a recent Times list was chock-a-block with crime thrillers and romances. Now, often only movie deals (for Umberto Eco’s 1980 novel The Name of the Rose, for instance) or, in the case of Salman Rushdie, widely publicized death threats can vault artistically ambitious works to the top.

What’s the worry? After all, a book’s “popularity can be understood as both proof and negation of its value,” Franklin says. Authors anxious to be taken seriously might cringe to see their stories sitting next to, say, Jaws (1974) on a shelf of bestsellers. But when that shelf becomes filled with a uniform bunch of mainstays, the public loses. Outliers, coupled with the influence that comes with top-selling status, can provoke the conversations that initiate change: Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) was, Franklin notes, a “good bad book”—and a bestseller.

THE SOURCE: “Readers of the Pack: American Best-Selling” by Ruth Franklin, in Bookforum, Summer 2011.

Photo courtesy of Flickr/Ann Althouse