Fall 2011

Sex offender registries have virtually no effect on public safety

– The Wilson Quarterly

Stigma, not safety.

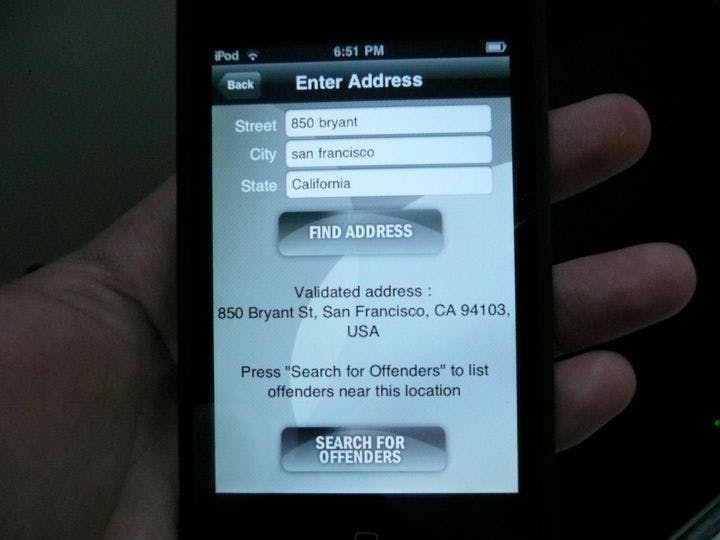

Conventional wisdom has it that sex offender registries keep the public safe. With the addresses of people who have been convicted publicly available (and, in most cases, searchable online), police and local residents can monitor offenders and guard against further crimes. Registries have become so accepted that, today, every state maintains a publicly accessible database for at least some category of sex offender. Amanda Y. Agan, a PhD candidate in economics at the University of Chicago, argues that many of these efforts are for naught.

Sex offender registries are very popular but they have virtually no effect on how many sex crimes are committed.

Agan analyzed the registries several different ways. First she looked at the incidence of rape and other sex offenses before and after the implementation of registries in all 50 states. She found that registries produced “no real change” in the number of arrests. In a second analysis, Agan studied the arrest records of roughly 9,600 convicted sex offenders following their release from prison in the mid-1990s. About half of the offenders lived in states that required them to register, and half in states that did not. Three years after the offenders’ release from prison, the two groups’ recidivism rates turned out to be virtually the same. In fact, those required to register were convicted of sex crimes at slightly higher rates.

Agan put one of the central premises behind registries—that knowing where sex offenders live predicts where sex offenses will occur—to a third test. Examining the correlation between the two factors in Washington, D.C. (and controlling for other variables known to influence crime), she found that the areas of residence of sex offenders played no role in the geographical distribution of sex crimes. Essentially, “there is little information we can infer from knowing that a sex offender lives on our block,” Agan observes.

If registries are ineffective at curbing recidivism among sex offenders, Agan contends, then they shouldn’t be adopted for people convicted of other crimes, such as methamphetamine use, a policy in force in a handful of states. And states, which employ a hodgepodge of registry strategies, should not impose stricter registration requirements, such as forcing offenders to wear GPS monitoring devices, until they’ve taken a hard look at registries themselves.

THE SOURCE: “Sex Offender Registries: Fear Without Function?” by Amanda Y. Agan, in the Journal of Law and Economics, Feb. 2011

Photo courtesy of Flickr/Violet Blue