Fall 2011

The Demise of Don Juan

– The Wilson Quarterly

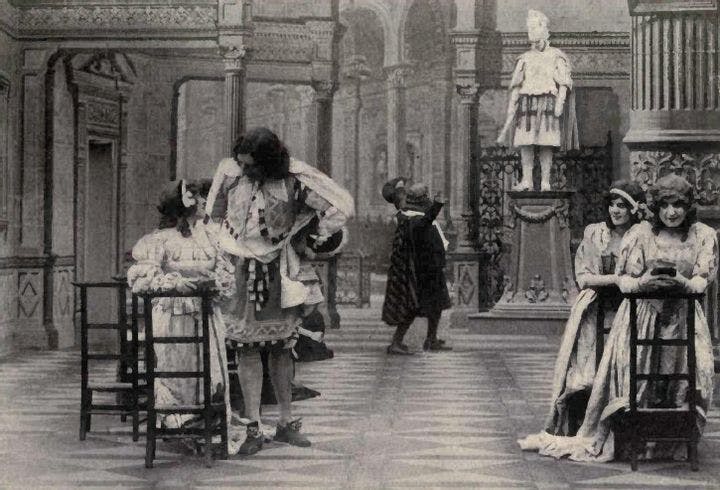

The early "Don Juan" offered commentators the opportunity to weigh in on society’s morals.

The mythical story of the energetic seducer Don Juan fascinated Europe for three centuries, stirring thinkers such as Søren Kierkegaard and Albert Camus to pen reflections on his character. But today the Don Juan myth is all but dead. How did one of literature’s most potent figures become what David Bentley Hart calls an “imaginative impossibility”?

The early Don Juan offered commentators the opportunity to weigh in on society’s morals, argues Hart, a First Things contributing editor. A longtime folk legend, the infamous sensualist made his first notable literary appearance in the 17th-century play The Trickster of Seville and the Stone Guest, by the Spanish writer Tirso de Molina. The early Juan had all of the legend’s trademark rakishness but was more dissolute than the one of later centuries. Writing during the Renaissance, when morality plays prevailed, Molina wanted the great seducer to stand as “a cautionary example of the vicious and debased state to which unrestrained appetite reduces a soul,” Hart writes.

Writers of the Romantic period, such as Lord Byron, added a more positive and philosophical dimension to Don Juan’s lustiness, transforming him from a figure of “unreflective sybaritism” into an idealist who pursued his desires in “Promethean defiance of the gods.” Romantics portrayed Don Juan’s bed-hopping as a hopeless quest for the perfect woman. He was “a tragic lover whose soul was worth contending for.”

The 20th century did not look upon the roué so kindly. The works in which Don Juan took a leading role, such as George Bernard Shaw’s Man and Superman (1903), were largely satires. In a culture increasingly defined by “glandular liberation and relaxed consciences,” Juan’s earnest yearnings had little resonance.

There’s more to Don Juan’s faded glory, Hart argues. Earlier incarnations of Juan, which had the seducer rejecting the reigning moral framework for one of his own devising, demonstrated “the godlike power of the soul.” The notion of a great if misdirected soul is all but lost in an age in which will is commonly thought of as a “random confluence of mindless physical forces and organic mechanisms.” The demise of traditional morality took a crucial frisson out of Juan’s story. “His proper element was that long cultural gloaming in which the old moral metaphysics retained its formal authority, but not its credibility.”

THE SOURCE: “A Splendid Wickedness” by David Bentley Hart, in First Things, Aug.–Sept. 2011

Photo courtesy of Flickr/Luke McKernan