Winter 2015

Countries and Western: The Geopolitics of Music

– David Schoenbaum

Generation after generation, in locale after locale, it’s true: When people join the modern world, their kids get piano and violin lessons.

FACING THE MUSIC CAN BE A CHALLENGE. Even the Bible says so: Worried what’s got into their employer, King Saul, an anxious staff urges him to look for a qualified string player as therapist. It did not end well. (Cartoonists are not the only artists who live dangerously.)

Things have not got easier since. In 1934, the murder of Sergei Mironovich Kirov set off the show trials that would cause some of the Soviet Union’s most prominent founding fathers to confess to crimes they didn’t commit. The same year, cheering audiences let the young Dmitri Shostakovich believe that his new opera “Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk” was a smash hit. Two years later, he learned from an editorial in Pravda that what he thought was a success was “muddle instead of music.” The experience would haunt him till his death in 1975.

Even performers took their chances. International prize winners might come home to victory parades, apartments, dachas, even a car. In 1935, the great violinist David Oistrakh returned from Warsaw as second-place winner in the Wieniawski competition, the first modern ‘violin Olympics.’ In 1937, he returned from Brussels as first-place winner of the first Queen Elisabeth competition, the gold standard of international tournaments ever since. He nonetheless lay awake in Moscow a year later with a small bag of necessaries packed just in case, wondering whether the footsteps on the stairs at 3 A.M. were coming for him or the neighbor.

By that time, Jews, both German and otherwise, were declared unfit to play in Berlin’s Philharmonie or Vienna’s Musikverein. But they were okay, even sought out, at Auschwitz a few years afterward, where a few like Henry Meyer, who survived to become a co-founder of the Lassalle Quartet, were able to save their lives by playing in orchestras as people around them died.

In more recent times in other places, playing in orchestras could as easily cost people their lives. During China’s Cultural Revolution, a tiny cadre of players was needed for the Little Red Book version of Chinese opera. But most, including some of China’s most gifted musicians, were harassed, humiliated, proscribed, assigned to the latrine detail, even hounded to suicide. In Afghanistan under the Taliban, music went the way of alcohol, pork and the ancient standing Buddhas blown to pieces in 2001. When Islamists took over Mali in 2012, ordinary citizens of one of the most musical countries in the world risked their lives if caught singing or even listening on the radio.

Yet recent visitors to the U.S. from Beijing and Kabul not only confirm that music is again allowed, but actively encouraged. In 1956, when an American tour seemed as likely as a moon landing, the People’s Republic founded the China National Symphony orchestra. In early 2013, it toured the U.S. A few weeks later, the Afghan Youth orchestra, founded in 2010, played arrangements of Ravel and Vivaldi, ingeniously reorchestrated for a mix of Western and Central Asian instruments, at Carnegie Hall and Washington’s Kennedy Center.

Washington’s National Symphony, itself only founded in 1931, was meanwhile on the road. The tour began conventionally with Spain, Germany and France. But its last stop was Oman, the little sultanate at the mouth of the Persian/Arabian Gulf that was identified by the United Nations Development Program in 2010 as the world’s most improved country since 1970. A year earlier, the Vienna Philharmonic performed at the Royal Opera House in Muscat, commissioned by Oman’s music-loving sultan in 2001, designed by architects in Honolulu, and managed by an American-trained Jordanian.

The travels and travellers not only connect a geopolitical dot or two. They tell us a thing or two about globalization, the workings of the world since the coming of the telegraph, steamboat and Internet, and the flowering of the Asian Rim.

YOU’D NEVER KNOW from the standard conservatory curriculum that music is the master metric. Yet Max Weber, the great German sociologist who gave us “charisma” and the “Protestant work ethic,” had it figured out a hundred years ago. The principle was simple: All music is equal. But a couple of happy accidents made the subspecies we think of as Western more equal than the others.

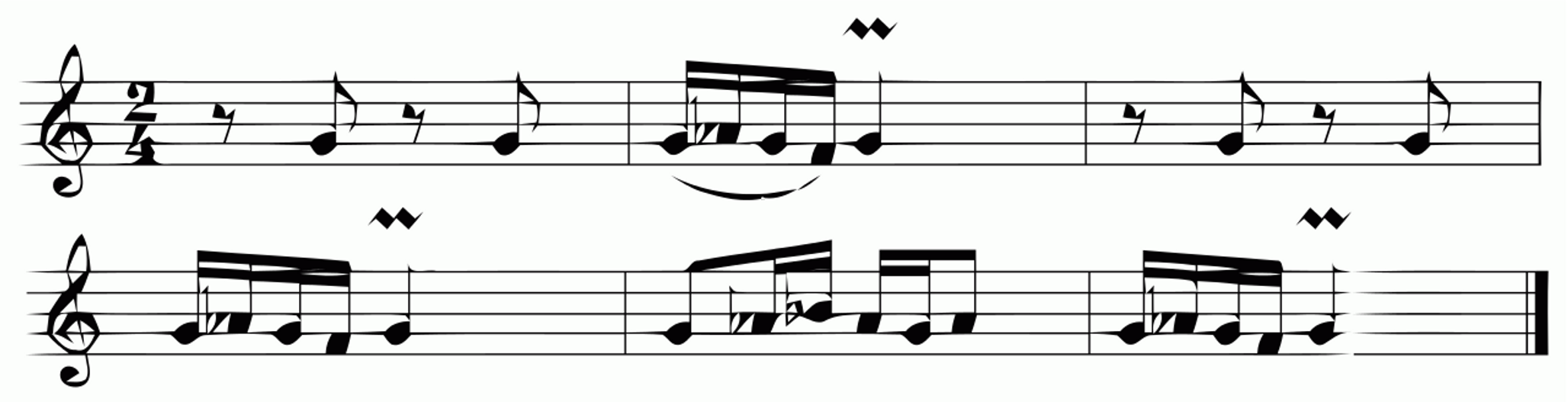

The first of the accidents — devised, like so many things, by the Greeks — is the endlessly adaptable 12-tone scale, with its unique capacity to surprise, delight, and inspire, whether played by the Berlin Philharmonic or sung by Justin Bieber. The second is a notation system invented by a 10th century monk that has allowed every tune played, sung, bellowed, hummed, whistled, or just thought about since Hildegard von Bingen, to be written, printed, and preserved as efficiently as words. For those with a taste for it, the theory of both is worth a one night stand with Oxford Music Online, but you can march in the high school band or sing “Take Me out to the Ballgame” without even being aware of it. What matters, as Weber was the first to point out, is the global appeal of a cultural product, born of the diatonic scale and Guido d’Arezzo’s do-re-mi, that had already become one of the Western world’s most successful exports by the turn of the 20th century.

By the threshold of the current century, what was clear to a Heidelberg sociologist in the era of Teddy Roosevelt could be seen and heard in action in any Chinese apartment house: When people join the modern world, their kids get piano and violin lessons.

Japan led the way while Johann Strauss was still composing waltzes. Determined to join what they couldn’t beat, Meiji-era Japanese studied French schools, German law, and British battleships. They learned to play baseball. They also learned to play the violin, even dispatching the Koda sisters to study with the era’s star teachers in Berlin and Vienna. With help from American missionaries and an ironic assist from the Japanese, who soon took over their country, Koreans got the message too. Then came China. A century after the process began, Dr. Shin’ichi Suzuki’s violin method was right up there with Toyota and the Walkman as one of Japan’s most successful exports to the West.

In the corner of world that is now home to 15 of the world’s 20 busiest container ports, beginner’s violins can be bought over the counter at Taoist temples. Harrods, the famed London department store, shut down its piano showroom after sales dropped by over 83 percent. Chinese department stores reserve whole floors for pianos made in Korea and Japan as well as China.

From southern California to St. Petersburg, conservatories now look to Asian students to keep them afloat. Asian musicians, the majority of them women, people the string sections of virtually every major orchestra this side of Vienna. David Chan, the concertmaster of the Metropolitan Opera orchestra is a Chinese-American. Daishin Kashimoto, the concertmaster of the Berlin Philharmonic, is a Japanese. The Philadelphia Orchestra and New York Philharmonic have announced special relationships with ensembles in Beijing and Shanghai.

Only one major region remains a holdout. Once known to the British as “East of Suez,” it has been known to American since at least the Eisenhower years as one big pain. But local or global, virtually everyone agrees that it is the region with the most conflicted relationship to the modern world.

EVEN THERE, OF COURSE, THERE ARE EXCEPTIONS. Israel, where a fugitive wave of Central Europeans was followed by a fugitive wave of Russians, is the most obvious. But for neighbors, already disposed to deny it regional legitimacy, the Israel Philharmonic is just one more proof that Israel is a foreign body.

Turkey’s Middle Eastern authenticity is harder to challenge. Like Japanese a half-century earlier, Mustafa Kemal made Western music a part of his modernization strategy. But like many Kemalist reforms, it was not an easy sell. In April 2013, Fazil Say, an internationally admired pianist, drew a 10-month suspended sentence for insulting Islam and offending Muslims. No fan of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, he then left for an extended stay in Berlin. But in December 2014, he was again concertizing in Istanbul.

In the mid 1990’s, Malaysia’s colorful prime minister Mohamad Mahathir added a concert hall as a complement to Kuala Lumpur’s shiny new Petronas Towers, then the world’s tallest buildings, and recruited an orchestra to play in it. But the job was outsourced to a London agency, and the closest approximation of a local player was a Chinese assistant conductor. “I’ve got it,” said one puzzled Malaysian on learning of the project. “It’s like bringing Jackie Stewart, the Formula One racer, before we had drivers or a course.”

Since then, Qatar has done much the same, and even hired a female Korean cellist as music director, just as Oman hired a woman arts manager as director of its opera house. But the players, again, are all imports. In Cairo and Baghdad, orchestras that go back decades really are made up of local players. But they exist on the margins, culturally equivalent to the rugby club at the University of Iowa.

A mix of some of the best and brightest young players from Israel, Palestine, Syria, Egypt, Jordan, Turkey, Iran, and Spain, the East-West Divan orchestra has its permanent home in Berlin. Created in 1999 by Daniel Barenboim, an Israeli from Berlin, and Edward Said, a Palestinian from New York, it has played for respectful audiences at Carnegie Hall and the London Proms. But it has yet to play in Israel, and has played only once – in 2005 – in Arab Palestine, where the players arrived with Spanish diplomatic passports.

In 1993, a National Conservatory of Music, since renamed for Said, opened in Ramallah. With branches in Bethlehem, Nablus and Gaza City, it now claims a thousand students, as well as a Palestine National orchestra that made its debut in 2010.

The sky darkens from there. From Cairo to Kabul, what we think of as Our Side tolerates, likes, even wants music. From Kandahar to Timbuktu, what we think of as Their Side hates and fears it. “Music is oxygen,” a terrorized north Malian told a reporter before the arrival of French troops. “Now we cannot breathe.”

“Music is against Islam” declared a leader of the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa, an al Qaeda spin-off active in Algeria, Mali and Niger. “We are not only against the musicians in Mali, we are in a struggle against all the musicians of the world.”

Established in 2010 after a four-year search for funding and faculty, Kabul’s Afghan National Institute of Music (ANIM) is as much a statement as an institution in a part of the world where musical instruments, according to an Islamist website, “are the wine of the soul, and what it does to the soul is worse than what intoxicating drinks do.” Patrons include the World Bank, the U.S., German, Dutch, Danish and Finnish embassies, the British Council, and even NATO.

Its director, Ahmad Sarmast, is a second-generation musician with degrees from the Moscow conservatory and Australia’s Monash University. Curriculum includes both native and Western repertory and instruments. An estimated half of ANIM’s students are orphans or street children on full support. One-third are girls.

The active faculty of 21 includes five U.S. citizens. Among the founding Americans was William Harvey, a Juilliard graduate, who arrived in New York practically on the eve of September 11. The Sunday afterward, he joined classmates at the 69th Regiment Armory to play for the most appreciative audience he’d ever encountered. For Harvey, who continued to play long after his friends had gone home, it was a life-changing experience.

He first invented an NGO with projects in Moldova, Qatar, and Cameroon, but it failed to pay the rent. In 2009, he accepted Sarmast’s job, teaching girls to play the violin in a city liberated from the Taliban while he was a freshman at Juilliard.

Harvey has since moved on to Argentina, where a concertmaster post in San Juan allows him to reactivate his NGO while composing and performing. But the ANIM website still lists him as a precocious emeritus, he retains an option on future visits, and his regard for Sarmast, his colleagues and the Kabul music scene, is unqualified. Like canaries in a mine shaft, their success and survival after and without him should tell us something worth knowing about what his – and America’s - years in Afghanistan accomplished.

With history to guide us, we might meanwhile keep our eyes on the rest of the region. When we see parents in Cairo, Damascus, Baghdad and Karachi start signing their kids up for Suzuki lessons, we can reasonably assume that something important has happened.

* * *

David Schoenbaum is the author of The Violin: A Social History of the World’s Most Versatile Instrument and a former scholar at the Wilson Center.

Photo design by Zack Stanton

Cover photo courtesy of the U.S. Embassy Kabul