U.S.-China Engagement:Regrettable or Inevitable?

Washington and Beijing need a relationship with each other more than they want one. Neither can succeed unless it finds a balance between its interests and values.

by Robert Daly

The United States and China are now adversaries. When and how this became true, and who bears responsibility for the wretched state of bilateral relations, are widely and fruitlessly debated. Over the past five years, under the Trump and Biden administrations, the United States' determination to bring China to task on multiple fronts or, at the very least, to no longer be China's patsy, brought an end to sustained dialogue. This spring, China's support for Russia's invasion of Ukraine, its amplification of Moscow's propaganda, and its belief that the United States “is the primary culprit in the war” have made reasoned discussion between the superpowers all but impossible.

This is unfortunate, as key issues demand consultation: Are we adversaries in all things, or can rivalry be limited and guided by rules? Is it possible to cooperate on transnational issues like climate change, fighting pandemics, and spurring development when mutual distrust between China and the U.S. is so high? And—the subject of this essay—if we are so profoundly opposed to each other, why do we remain close partners in many ways?

Both countries' confusion is reflected in the gap between their heated rhetoric and the stubborn facts of their relationship. American politicians call China an “existential threat” and “evil empire,” while China's Communist Party labels the United States “the Empire of Lies.” But the U.S. is still China's top trading partner and China ranks third for the United States. What to make of this?

To illustrate the dueling realities driving U.S.-China tensions, and to suggest principles for managing them, this essay employs the structure of China's Doorway Couplets.Doorway Couplets (对联) are vertical strips of paper pasted on either side of traditional Chinese doors during the Spring Festival. They feature black ideographs on red paper and are intended to bring good fortune in the New Year and show off the household's breeding to envious neighbors. The strips can be read vertically, first left, then right, to yield a poem or aphorism; but they can also be read horizontally—the first characters on the left and right strips, then the second characters, and so on—to yield a series of ironic pairings that enhance and sometimes confound the more straightforward vertical sentiments.

In the lists that follow, passages in the left column can be read together to form an argument for decoupling from China. This is the case made by Americans who view China as the greatest threat to our security and see the past forty years of bilateral engagement as regrettable. Texts on the right, read in series, argue that Sino-U.S. integration is inevitable, no matter how distasteful we find each other's mode of governance.

The horizontal reading of paired items provides the most complete, but least conclusive, view of U.S.-China relations. It acknowledges complexity and compromise. It argues that the rivalry can be managed with caution.

Beijing, China July 24th 2014: Ancient Gate or doorway with protective stone guardians of Dongcheng District in Beijing, Peoples Republic of China.Shutterstock/Alan Carter

Trade: By 2011, China's WTO accession had caused the loss of 2.4 million American jobs. The $285.5 billion U.S. goods and services trade deficit with China in 2020 was due in part to China's subsidies for state-owned enterprises. China's exports to the U.S. have risen by 31% since President Trump launched the trade war in 2018. China hasmade only 57% of purchases promised under the 2020 Phase I trade deal, suggesting that U.S. negotiators were played.

Trade: As the top market for U.S. agricultural exports, China is essential to the heartland economy. Its purchase of our goods and services has produced more than 2 million American jobs and has earned billions in profits for U.S. corporations, their employees, and shareholders. The import of its low-cost products results in $1,500 in annual savings for American families. Before COVID, Chinese students spent nearly $15 billion in the U.S. every year.

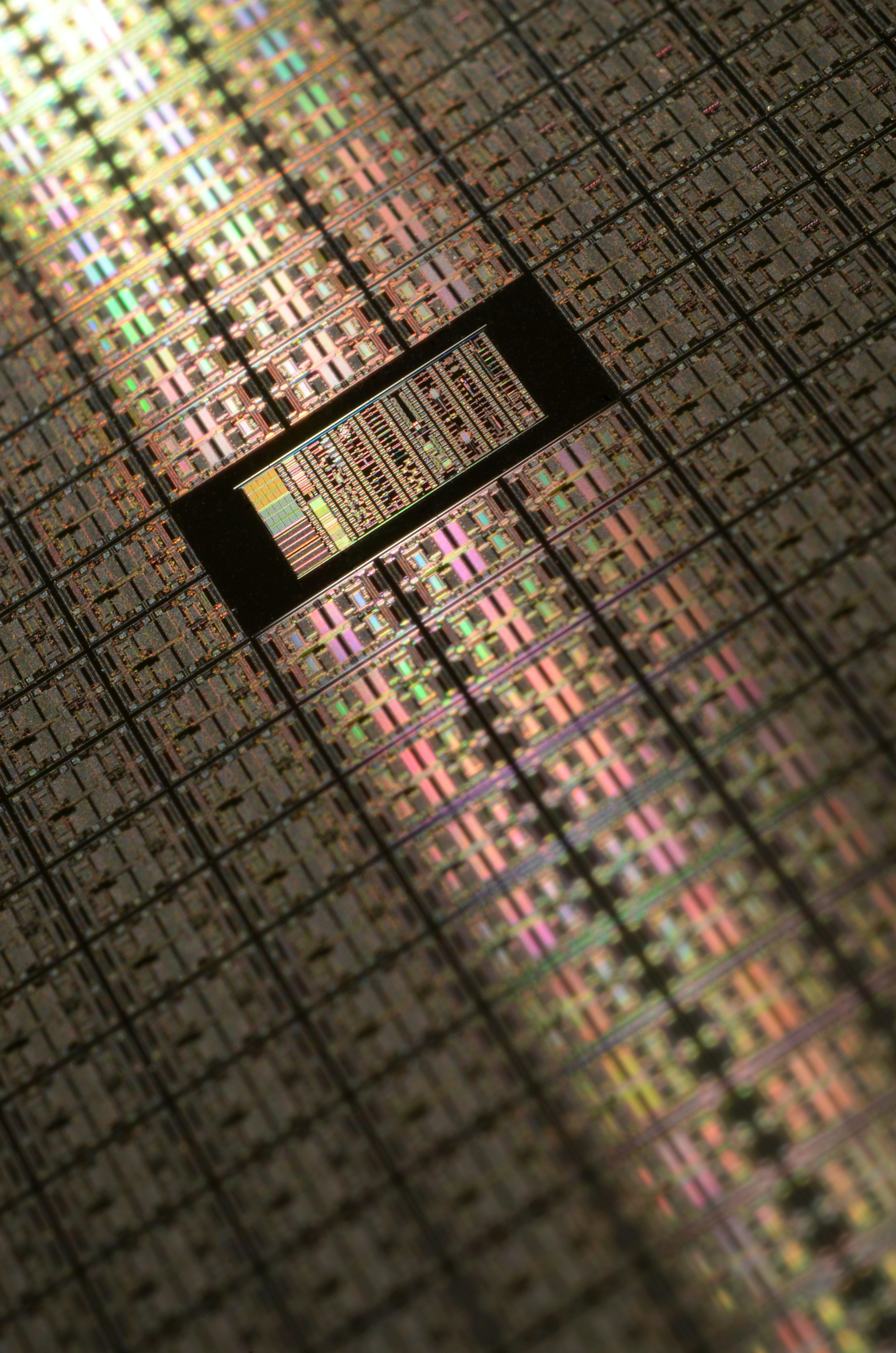

Critical Supply Chains: The U.S. depends on China for rare earths used in computers, weapons, appliances, and the energy industry, medicines and medical precursors, solar panels, and many manufactured goods. This makes the U.S. susceptible to Chinese economic coercion. Assuring domestic supply chain resilience requires decoupling from China, developing alternate sources of supply, and adopting an industrial policy, all of which will cost Americans dearly.

Critical Supply Chains: Americans depend on China for vital goods because China makes them at lowest cost, which benefits U.S. consumers. China is also dependent on the United States, or nations whose export policies it can dictate, for semiconductors and other components of high tech products. Threatening to cut off China's access to tech components incentivizes China to develop domestic alternatives, which harms U.S. industry in the long run.

Investment: China can invest in U.S. industries that are off-limits to American capital in China, like health care, cloud computing, social media, and film. U.S. high tech companies such as Qualcomm, Microsoft, and Apple that sell products and make R&D investments in China are accused of building the technical capacity and power of a nation that seeks to undermine the U.S. American funds that buy Chinese bonds and equities also contribute to China's strength.

Investment: America is the world's most powerful nation in part because it has the world's top companies. Those companies cannot retain their preeminence if they can't sell into the world's biggest market. Qualcomm, Micron Technology, and Texas Instruments earn 67, 57, and 44 percent of their profits in China, respectively. If U.S. funds don't invest in China, they may not be able to earn the yields needed to secure the retirements of U.S. public sector employees.

Technology: China's technology theft costs U.S. industry between $225 and $600 billion annually. Its Made in China 2025 program aims to make China the global tech leader through means that may violate its WTO commitments. Beijing's Civil Military Fusion policy and 2017 National Intelligence Law ensure that any technology and data brought to China that might benefit its military will be used for that purpose. S&T decoupling from China is essential.

Technology: S&T decoupling from China would isolate the United States from the global knowledge system, harming its universities, laboratories, and corporations. America needs one million more STEM professionals than it currently trains. China is the top source of foreign STEM students in the United States and 90% of them still work in America ten years after earning PhDs. We cannot cut ourselves off from that talent flow and retain S&T leadership.

Pandemic: China's refusal to permit a thorough, objective, international investigation into the origins of COVID-19 leaves the world in a state of potentially fatal ignorance about the nature of the greatest threat to global health and prosperity in the 21st century (thus far). Scientific and medical cooperation with China is impossible under such circumstances.

Pandemic: America's criticism of China's COVID-19 response makes it impossible for Beijing to work with Washington to anticipate, identify, and combat the next global pandemic, which could well originate in China and which could be more devastating than COVID. Scientific and medical cooperation is therefore urgent, no matter how unpalatable. Hold your nose and get to it.

Climate Change: China has been the world's leading emitter of greenhouse gases since 2006. Despite repeated pledges to go green, China's carbon emissions will keep increasing through at least 2030. It exports coal-fired power plants and refuses to work with the U.S. to tackle global warming due to America's criticism of China's human rights record—a wholly unrelated issue.

Climate Change: Whether the superpowers like it or not, the world looks to China and the U.S.—at 20%, still the world's leading cumulative emitter of greenhouse gases—to build coalitions and develop technologies that will save humanity from its greatest pending disaster. Serious countries can work together for the common good even if they don't like each other.

Norms/Ideology: The Chinese Communist Party's domestic power and global influence requires the promulgation of beliefs about human flourishing and governance that are odious to liberal democracies. The CCP's proposition is that people can and should be fulfilled when their material needs and desires are met, which requires a level of stability that only authoritarian governments operating in secrecy can provide. Beijing believes First Amendment rights imperil the state and its citizens.

Norms/Ideology: The Chinese Communist Party is not China. The story of modern China is the story of change at an unprecedented scale and pace—change that is ongoing and undetermined. The U.S., through its positive and negative examples, through broad engagement, and through criticism and deterrence has been a major catalyst of China's evolution for 40 years. Decoupling will obliterate channels of influence and make China more autocratic, fearful, and self-regarding than it already is.

Allies: Russia, North Korea, Iran, Cuba, and a growing list of Arab nations are drawing closer to China. Beijing leverages its wealth and communications technology to make developing countries in Africa, South America, and Central and Southeast Asia dependent on and deferential to China. These relationships form an emergent Sinosphere that opposes U.S. values and leadership. The U.S. must strengthen its own alliance network to counter China's.

Allies: Many nations that benefit from trade with China prefer American models to Beijing's and look to Washington to check China's military and political power. Their goal is to hedge between the superpowers, not make a final choice between them. As Singapore's prime minister put it recently, a U.S. “everyone but China” approach to the Indo-Pacific will be rejected by the region. America must strengthen its partnerships and performance without forming blocs.

Read vertically, these couplets form the poles, or instincts, between which the United States' still-uncertain China policy wavers. Conversely, a horizontal reading indicates the difficulty of reconciling our instincts with the risks and costs of any policy direction the United States might choose.

A High Threshold

At the bottom of traditional Chinese doorways, there is a threshold (门槛) made of wood or stone over which any visitor must walk. The more distinguished the family, the higher the threshold, the more awkward the step. The threshold for managing U.S.-China relations successfully—for moving forward without breaking our legs—has never been more daunting.

This edition of The Wilson Quarterly asks an old question under new circumstances and with special urgency: Under what circumstances can the United States work with countries that reject our values in pursuit of our interests? What actions of other countries so violate our principles or threaten our well-being that we cannot cooperate with them, even if it costs us dearly?

China's combination of an enormous population, vast wealth, global ambition, and aggrieved nationalism makes these calculations trickier than usual. On America's side, the moral absolutism of our political discourse often blinds us to the distinction between interests and values, resulting in grossly inconsistent policies that offend allies and adversaries alike. As George Kennan wrote in Morality and Foreign Policy, in 1985:

A lack of consistency implies a lack of principle in the eyes of much of the world; whereas morality, if not principled, is not really morality. Foreigners, observing these anomalies, may be forgiven for suspecting that what passes as the product of moral inspiration in the rhetoric of our government is more likely to be a fair reflection of the mosaic of residual ethnic loyalties and passions that make themselves felt in the rough and tumble of our political life.

— George Kennan

Preaching has never worked with China anyway. The People's Republic of China is too big to ignore and the Chinese Communist Party is too self-certain to persuade. America cannot isolate China without isolating itself; nor can it impose costs on China that are not felt by Americans. We've faced nothing like it in our history. How to proceed?

Outlining a full China strategy is beyond the scope of this essay. The dilemmas noted above do suggest several principles for navigating between our interests and values in relation to China, however, some of which may be applicable to other cases presented in this volume:

- Distinguish between real threats to our security and mere violations of our values—between the dangerous and the distasteful. Speaking of them with equal vehemence confuses the American people about the nature and goals of our challenges. Speaking of every troubling country as a manifestation of evil alienates thoughtful people in those countries and blinds us to opportunities for compromise.

- Because complete decoupling from China is unaffordable, the U.S. should spurn final remedies in favor of mitigation and risk management strategies that buy time. We need time because China, the United States, and the global environment are all changing rapidly and unpredictably. America needs time to adjust to these evolutions, to repair its own institutions, and to improve its performance and global standing.

- Gradualism will require ongoing dialogue with China, which is difficult and often unpleasant. We have found ways to fund expansive military budgets, AUKUS, and a more active Quad; it should be possible to fund a more vigorous diplomacy with China and the region and to build stronger economic relations in the Indo-Pacific region.

- Approach the problem of moral compromise in foreign policy by moving one step at a time, in the knowledge that hypocrisy is neither fatal nor rare.

Editorial Credits

- Written by Robert Daly

- Edited by Stephanie Bowen

- Design by Marquee