Summer 2022

Putin’s Imperial Dream

– William E. Pomeranz

Putin's motivations, and the long term consequences

The Russian attack on Ukraine took most experts and citizens by surprise. In retrospect, however, Putin telegraphed his ambitions in his 2020 constitutional amendments, which, among other things, emphasized the Russian Federation’s right to defend ethnic Russians abroad and further stated that Russia could not give up any land once it had been incorporated into the country.

These two new constitutional principles, combined with the rewriting and reduction of Russia’s legal obligations under international law, set the stage for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The ripples of Putin’s war, however, go far beyond the battlefield and have touched Russia’s most sacred memory of them all: The Great Patriotic War. Indeed, as Putin pursues his 21st century imperial designs in Ukraine, he must define what unites his now expanding, multinational country.

Putin launched his attack on Ukraine under the pretext of protecting Russians in the Donbas from imminent violence—a blatantly false charge—and to expand Russian territory. Putin has designs on incorporating Donetsk, Luhansk, the newly captured region of Kherson, and maybe other regions, into the Russian Federation. With this expected annexation of territory, Putin would have succeeded in creating a strategic land bridge that links mainland Russia to Crimea.

In starting this brutal and unprovoked war on Ukraine, however, Putin has forever tarnished the one historical event that binds the Russian Federation together, namely the Soviet Union’s victory in World War II. The search for national unity has become a growing fixation for Putin, but Russian history provides few satisfactory role models who have achieved this objective. Peter the Great still serves as the obvious default choice. Putin recently praised him, saying the Russian state remains almost unchanged since the 18th century, adding that Peter did not take away any territory from Sweden in the Great Northern War, so much as return what was Russia’s.

In reality, Putin is left with one unifying event to rally the Russian people: the Soviet Union’s victory in World War II.

Putin is much more loath to turn to Lenin and the Bolshevik Party for positive historical symbols. On several occasions, Putin has accused Lenin of planting a time bomb in the heart of the Soviet Union by basing its internal construction on the nationality principle. He further criticized Lenin for surrendering territory to Germany just before Germany surrendered. “We lost to the losing party, a unique case in history,” Putin declared in years past.

Putin skipped any discussion of the centenary of the 1917 Russian Revolution as being too divisive. Four years later, however, he dedicated a monument in Crimea commemorating the end of the Russian Civil War. The ceremony was particularly revealing about Putin’s efforts to create a usable past. He opened the memorial on National Unity Day, formerly the holiday marking the 1917 Revolution, stating that “in Crimea one gets the keenest sense of this live, unending bond.” Putin also declared, “Sevastopol and Crimea are now with Russia and will stay with it forever, because this was the expression of the sovereign, free, and uncompromising will of our entire people.” The inscription on the monument further read, “We are a single people, and have only one Russia.”

At this 2021 ceremony devoted to reconciliation and historical remembrance, Putin nevertheless managed to misrepresent the facts. According to him, one reason for placing this monument in Crimea was because the so-called philosopher’s ship—the boat that carried some of Russia’s leading intellectuals into exile—sailed past Crimea. Putin said that the ship carried those “who left their motherland and emigrated.” In fact, Lenin banished these freethinkers from the Soviet Union under threat of execution if they ever returned.

30 years after the end of the Cold War, Russia is once again on the outside looking in. The irony is that Ukraine finds itself in a similar position, but with radically different objectives.

Putin is also on shaky ground when lamenting the exodus of Russia’s most talented citizens. His invasion of Ukraine sparked the largest migration and brain drain from Russia since the 1917 Revolution.

In reality, Putin is left with one unifying event to rally the Russian people: the Soviet Union’s victory in World War II. Putin has extended the natural lifetime of this victory to another generation by creating the immortal regiment, where the relatives of veterans march to commemorate the sacrifice of their ancestors. Putin invariably leads this procession, proudly displaying a photograph of his father, a World War II veteran.

Putin returned to this message of unity on May 9, 2022, the 77th anniversary of Victory in Europe Day. He opened his speech by saying that this anniversary “has been enshrined in world history as a triumph of the unified Soviet people, its cohesion and spiritual power, an unparalleled feat on the front lines and on the home front.”

Yet in the aftermath of Putin’s bloody and criminal war, it is doubtful whether World War II still plays this singularly unifying role. Clearly, Ukraine no longer feels attached to this history, since Putin has falsely and maliciously transferred Nazi crimes to Ukraine to justify this war. Russia further stands accused of the same criminal actions as the Nazis—crimes against humanity, the crime of waging an aggressive war, and genocide—along with the massacre of innocent civilians and the deportation, or filtration, of Ukrainian citizens. The historian Francine Hirsch has identified the underappreciated role that the Soviet Union played at Nuremberg and the establishment of the post–World War II human rights architecture. Russia’s leaders now face similar charges—and potential legal consequences—for the invasion of Ukraine.

The unifying symbol of World War II remains problematic for other reasons. Russia always had difficulty explaining the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact—the 1939 agreement between Hitler and Stalin that divvied up Poland and gave the Soviet Union free reign in the Baltics. Putin and the Duma have dealt with this inconvenient episode by introducing administrative penalties for equating Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, and any public statement denying the decisive role of the USSR in defeating the Nazis. Russia’s preeminent human rights group, Memorial, was recently declared a foreign agent and dissolved because, in the eyes of Russian law enforcement, it had created a false image of the Soviet Union as a “terrorist state.”

The post–Cold War security architecture—and attempts to integrate Russia into Western and global institutions—has reached a dead end.

Putin’s call for unity has been accompanied by a host of repressive laws—the Foreign Agents law, the Undesirable law—and the doubling-down on the principle of national sovereignty. On the latter front, Putin has been almost too successful. Russia has essentially pulled out—or been expelled—from the global institutions that serve as the backbone of the post–Cold War global order. Russia is no longer a member of the Council of Europe and, consequently, it is no longer subject to the European Court of Human of Rights. The United States revoked Russia’s permanent most-favored-nation status, which was the primary reason for Russia joining the World Trade Organization in the first place. Russia has also backed away from global trade by allowing parallel imports, which is in violation of international copyright regulations, and threatening to nationalize foreign-owned industries.

The list goes on.

The European Union expelled Russian banks from the bank messaging system (SWIFT), and therefore from the global payment system. Russia spent more than a decade trying to integrate global education standards through the Bologna process so that domestic degrees would be recognized as the equivalent of European degrees. No problem. Russia has now unilaterally withdrawn from the Bologna process. Russia has also been suspended from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the Artic Council, and by an overwhelming vote, from the UN Human Rights Council.

So, 30 years after the end of the Cold War, Russia is once again on the outside looking in. The irony is that Ukraine finds itself in a similar position, but with radically different objectives. The war has revitalized NATO and the Western alliance, but it appears that Sweden and Finland will join NATO before Ukraine. Ukraine’s other main geopolitical goal is to join the European Union. On this front, Ukraine has now achieved candidate status to the EU, but this recognition only starts the clock for what most likely will be years of negotiations to obtain full EU membership.

Much depends on the military situation on the ground. The current consensus among analysts suggests that the two countries may be engaged in a war of attrition, with both sides suffering from shortages of supplies, weapons, and manpower. Since neither country appears willing to admit defeat—political suicide for both Putin and Zelenskyy—a protracted conflict seems the most likely result.

Although the ultimate endgame is still in doubt, new facts on the ground must be considered. To begin with, the theoretical unity between Russia and Ukraine—left over from World War II—has been permanently broken, and only time will tell whether Putin can rely on this increasingly distant memory to preserve domestic solidarity and stability. The post–Cold War security architecture—and attempts to integrate Russia into Western and global institutions—has reached a dead end, as has the terminology used to describe the former Soviet Union. Indeed, the term “post-Soviet” is no longer relevant since Ukrainians heroically have now fought—and died—to secure their country’s European future. One thing is certain: as long as the war continues, there will be no innocent bystanders. The rest of the world—whether it be in food supplies, energy prices, human migration, or global financial markets—will continue to feel its aftershocks.

William Pomeranz, the director of the Woodrow Wilson Center’s Kennan Institute, is an expert guide to the complexities of political and economic developments in Russia, particularly through the lens of law. He leverages extensive, hands-on experience in international and Russian jurisprudence to address a wide range of legal issues, from the development of Russia’s Constitution to human rights law to foreign investment and sanctions. He is also the author of Law and the Russian State: Russia’s Legal Evolution from Peter the Great to Vladimir Putin (Bloomsbury, 2018).

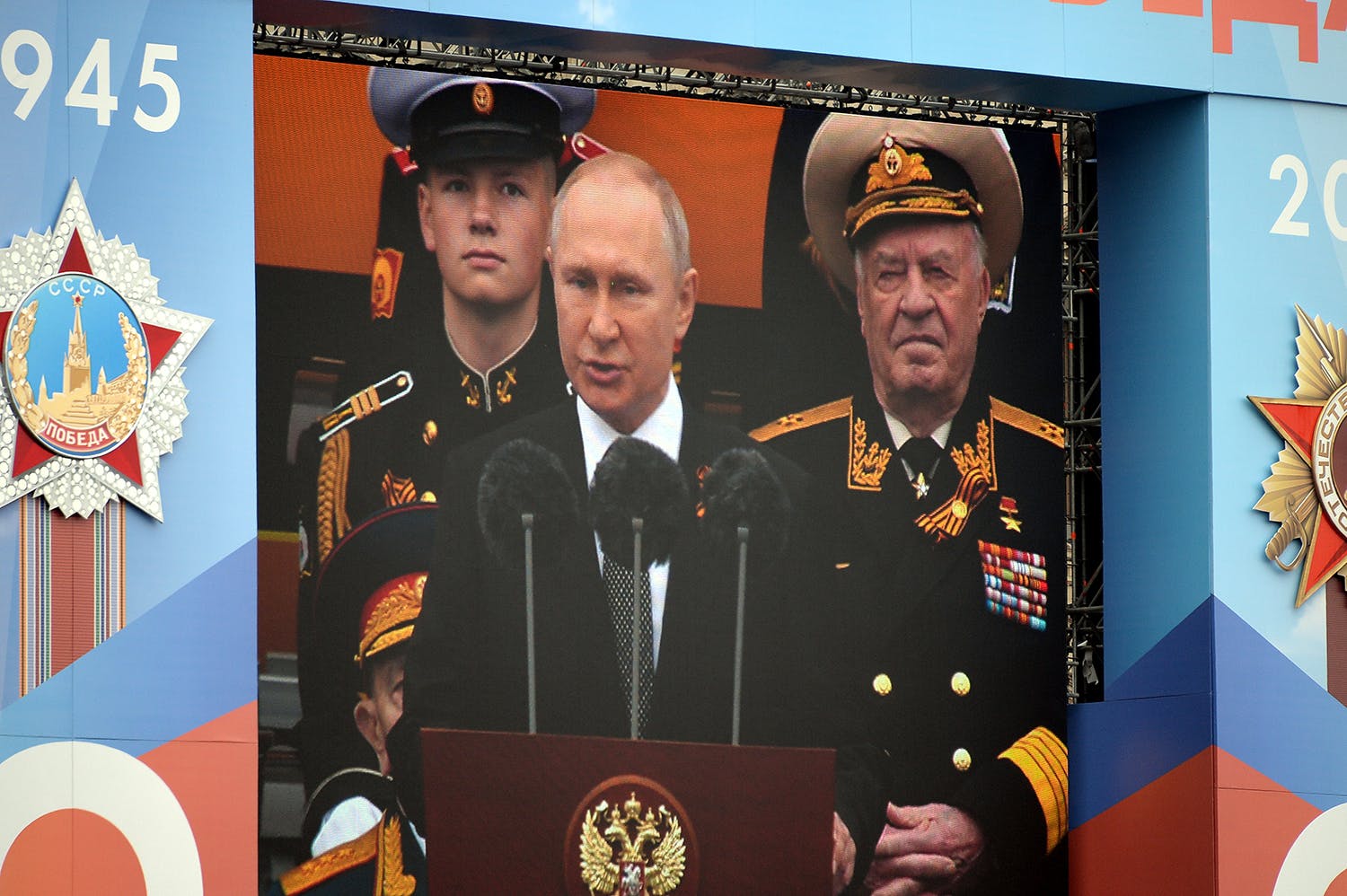

Cover photo: Victory Day celebration on Red Square on May 9, 2022 in Moscow, Russia. Shutterstock/Igor Dolgov.